Blue Bloods

Generations and Generations in Turquoise

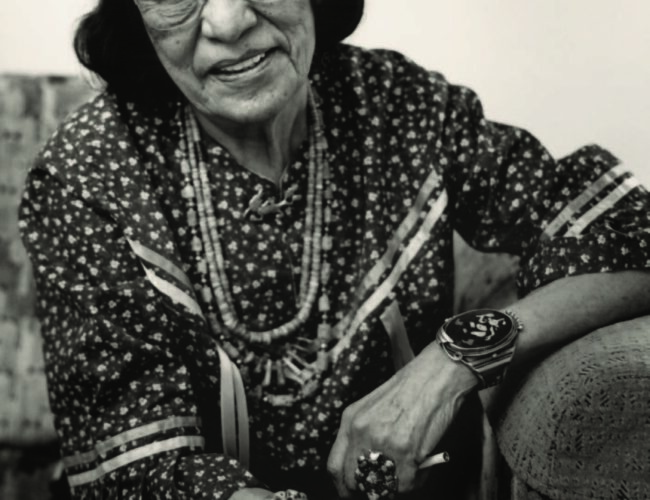

Pablita Velarde, the author’s grandmother, adorned in turquoise at her home in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Photograph by Joanne Rijmes, 1988. Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA), Neg. No. 189263. From the Santa Fe Living Treasures Collection.

Pablita Velarde, the author’s grandmother, adorned in turquoise at her home in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Photograph by Joanne Rijmes, 1988. Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA), Neg. No. 189263. From the Santa Fe Living Treasures Collection.

BY MARGARETE BAGSHAW

Gobs and gobs of turquoise, draped over the old, young, and middle-aged women, men, and everyone in between. Some of them look like Christmas trees, walking around Santa Fe in their uniform: felt hats with hat bands, Pendleton or leather coats with silver and turquoise buttons, boots with silver tips and some sort of ranch wear for ladies.

Concho belts are a must! Or at the very least a concho belt buckle. She’s wearing bracelets up to her elbows that even Wonder Woman would envy. He’s wearing a turquoise squash blossom necklace that weighs more than his wife with her bracelets on, and she’s wearing one too. Santa Fe Indian Market is the best place to see the most colorful combinations.I wonder if any of these people have ever heard the names Millicent Rogers or Martha Reed? These two mid-century immigrants to Taos concocted an enduring style: Navajo-inspired broomstick skirts cinched with concho belts, crisp white cotton or soft velvet blouses with silver buttons. Pounds of Indian jewelry bedecked them and their imitators, the customers of Reed’s Martha of Taos dress shop. Their influences echo everywhere you turn in Santa Fe throughout the year.

Or the scholars . . . you can tell them a mile away. She’s wearing the traditional PhD graying bob under her flat-rimmed straw hat, with a turquoise and silver hatband and wire-framed glasses attached to her neck by a turquoise and silver eyeglass chain. He, her younger colleague (or is he something more?), is sporting a Panama hat that covers his thinning brown hair, and a tiny ponytail tied back by a piece of leather, cool among Santa Fe guys. The hat brim is bent (from being out on a dig?); his hatband is leather, brown, or black with one small silver and turquoise concho on the side, glued on by repair. He sports bent wire-framed glasses with sunglass attachments. Circling his neck is a leather-macramé choker with one piece of turquoise, made by his girlfriend who is an art student at UNM. He has a silver concho on his belt because he can’t afford to replace the one with turquoise that his wife gave him a couple of years ago when he defended his dissertation.

It’s fun to people watch and guess their stories. They all enthusiastically support the local social, educational, and economic development of New Mexico, and they are all part of its story.

I grew up as part of Pueblo society, which held turquoise in high regard. Kingman, Bisbee, and Lone Mountain were buzzwords in the jewelry world of the Southwest. When I opened a new fancy box of Crayolas, the 100-count with the crayon sharpener built into its rear, the first colors I’d look for were red, gold, silver, and turquoise.

As a little girl, I understood that turquoise was a sign of importance and sometimes wealth. I didn’t know why, but I knew that the more you had, the better. My mother, Helen Hardin, and my grandmother, Pablita Velarde, both professional artists, wore lots of silver and turquoise jewelry when they had to be seen at art shows, museum events, and la-di-da parties. If I was along, Mom made sure I was wearing either a turquoise choker or some turquoise hair thing. My first earrings after my pierced ears healed were little turquoise flowers on silver posts.

These two ladies were successful but not wealthy, so bartering with artists and jewelers was always a preferred option for augmenting their collections. They liked paintings, prints, weavings, pots, but if they had lots of anything it was jewelry. Mom would make a point of rewarding herself after a good show with something gorgeous, and most certainly by a notable jeweler such as Richard Tsosie or Charles Loloma. It was very important to her that clients understood that she spent her money on things of value rather than on the frivolous activities of the seventies.

Grandma liked trading at Indian Market and at the Eight Northern Pueblos market. Sometimes jewelers would come to her booth and sheepishly ask if she would consider trading a painting—they just wanted to have something of hers. She’d say, “Well . . . let me come look to see if there’s anything I want.” So she’d excuse herself to go for “a walk.” Half an hour later she’d come scurrying into the booth and quickly hide something between her hands and chest, smiling from ear to ear, like a cat with a mouse. Then the other artist/jeweler would come back to the booth, and she’d give him or her a choice of dolls, paintings, or books, something of comparable value to make it fair. Each side always felt like they’d gotten the better deal.

It was very common to hear compliments. “Oh, Pablita! Your turquoise is so beautiful! How do you find such beautiful jewelry?” Or, “Oh, Helen, you always have such gorgeous jewelry. But you don’t need it because you’re so beautiful anyway . . . I wish I had your eyes.” Iridescent turquoise was Mom’s favorite color of Cover Girl eye shadow; she’d blend it with the iridescent brown, and all of a sudden her big brown eyes sparkled like the turquoise hanging from around her neck and ears.

I was taught at an early age the difference between really good turquoise and the treated turquoise, fake turquoise, or chrysocolla that were being sold as turquoise. Grandma could spot chrysocolla across her yard, from her front door. I know, because I was scolded for wearing something fake. She said, “Shame on you, with all the jewelry we have, why would you wear something fake?” It went in the trash. That happened once. Later I realized that she sometimes ground chrysocolla for the turquoise color on her earth-pigment paintings, if she didn’t have low-grade turquoise.

Some of Mom’s friends have proudly told me that she helped them buy a ring or a necklace, when they were walking on the plaza or at Indian Market. “Helen said, ‘If you buy that you’ll be sorry! Let me help you buy something that won’t dissolve, melt, or turn green!’ As only Helen could say in her eloquent way!”

Looking at the beautiful pieces of handmade jewelry that my grandmother and mother worked so hard to collect, I know that they were seriously smart about getting the best quality of work and stone they could. Their collections reflected their personal taste. Grandma collected old-fashioned big stones, turquoise nuggets, and heishi in her bracelets and fetish necklaces. Mom collected both traditional and contemporary jewelry, sometimes gifting something modern to Grandma. Grandma wouldn’t have bought the modern piece herself, but she most certainly would not turn her nose up at it either. Grandma wore her jewelry with anything from a smart, tailored suit from Talbots to a traditional Pueblo manta with moccasins and trimmings, or a shirt and slacks marked down 30 percent from JCPenney. Never with her Kmart clothes, which were for work only.

When I lost my mother Helen to breast cancer, it was her wish that I have her jewelry, and it was the same with my grandmother, when she died of pneumonia twenty-two years later. I’ve gone through phases of wearing certain pieces of this or that, but I’ve also started collecting my own pieces as well. I wear something of Grandma’s, something of Mom’s, and something of mine when I’m lecturing about our family or at some la-di-da event.

I feel very close to them when I go through their beautiful jewelry, remembering what they bought or traded for, at this or that event. I think about how this turquoise bracelet looked on Grandma’s gnarly old wrist, which worked so hard, or how Mom’s beautiful necklace and earrings complimented her gorgeous eyes and glamorous smile. I even remember her staying in bed one morning for hours while she restrung a double strand of turquoise that she said was very old. I didn’t care; I was hungry for breakfast, but she was focused on her task, her delicate fingers, so skilled at wielding a paint brush, pushing the needle through the tiny holes. I still have that necklace, but funny, it needs to be restrung again.

People ask why I don’t wear more of Mom’s and Grandma’s jewelry. Wearing their jewelry for me is a privilege I don’t want to overspend. I’m afraid of losing these family treasures or getting paint on them. As a very young woman I did lose a pair of my mother’s jacla earrings. But what’s the point in having these jewels if I’m not enjoying them? Collecting my own jewelry to supplement theirs gives me a charge, just as their collecting did for them. Purchasing from or trading with other talented and respected artists is itself an accomplishment. Buying a new piece gives me a sense of self-reward for painting a successful show. After one successful Indian Market, I went into Shiprock Gallery and bought myself a beautiful old pair of jacla earrings from the 1950s; the loops of turquoise and coral hang from silver buttons. Honestly, they are better than the ones I lost!

My own daughter, Helen, has her own very favorite pieces of her Grandma Helen’s jewelry that she likes to wear—a necklace, earring, and bracelet set with mother-of-pearl flowers. Although it’s not turquoise, she appreciates the important place this blue stone holds in her lineage.

Turquoise has value, prestige, and healing properties. It is house trim on our brown adobe houses, because it says something bright and beautiful on something solid and earthy. It is a piece of the earth possessing the spirit of the desert. Turquoise is the color of Caribbean water, caused magically when light hits particles, such as green phytoplankton, in the water. With the light from the sun, reflected from the white sand on the bottom of the ocean (coral eaten and digested by parrot fish), in combination with the blue reflection from the sky, “Caribbean turquoise blue” shines forth.

Turquoise exists and is mined all over the world. It has great historical and cultural significance. When I was a little girl, I had a book about the ancient Egyptians that I loved, and ever since then, I’ve been fascinated by Egyptian culture and art, and by its powerful female rulers. The oldest known turquoise is on a gold bracelet worn by a mummified Egyptian queen, seven thousand years old. She set the standard.

Turquoise is beautiful as a rough hunk of stone on a necklace, or as a formed, smooth, modern composition. People don’t have to wear “the uniform” to wear turquoise. It looks good with a t-shirt, blue jeans, and sneakers. (My own mother had a t-shirt with a squash blossom necklace printed on it.) It perks up the drab; it stabilizes the overly bright; it brings notice to blue eyes; it energizes brown or hazel eyes. It dances with red hair, red lipstick, and red clothes. It stands out on black, it jumps off of white, and what it does to purple is erotic.

People from all over the world buy one small piece in a ring or a pin, and feel like they’ve joined the club. “I have a turquoise ring I bought on the plaza under the portal,” they say, and the event is as important to them as the treasure.

It isn’t a diamond, and it isn’t gold, but it goes with everything!

Margarete Bagshaw’s paintings are on view at the Golden Dawn Gallery in Santa Fe, which she operates with her husband, Dan McGuinness. Bagshaw and McGuinness are also the founders of the Pablita Velarde Museum of Indian Women in the Arts, in Santa Fe. The Museum of Indian Arts and Culture presented a one-woman retrospective of her work in 2012, and the Smithsonian-affiliated Ellen Noel Museum in Texas recently presented an exhibit of twenty-five large paintings by Bagshaw. She is the author of the memoir, Teaching My Spirit to Fly, and contributed the essay “Christmas with Grandma” to El Palacio (Winter 2012).