Pot of Many Lives

BY PENELOPE HUNTER-STIEBEL

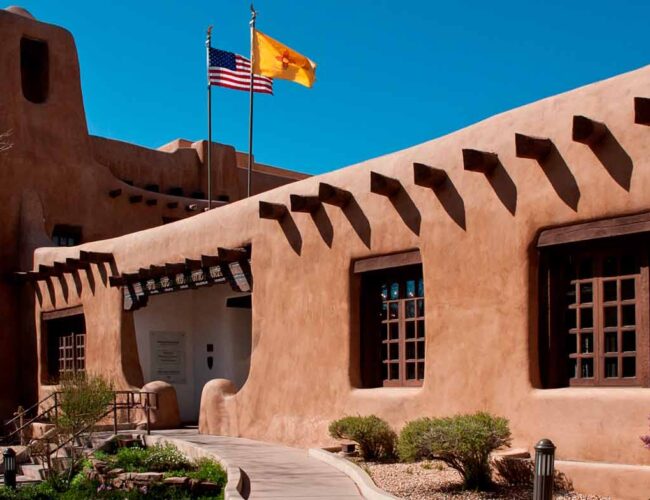

Among the many pots at the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture, one in the cooking section of the exhibition Here, Now and Always calls to me. The women of Acoma have long produced awe-inspiring ceramics, especially the tall, thin-walled ollas that they traditionally carried on their heads, bringing water from the springs below Sky City. But “my” Acoma pot is a large, heavy bowl for kneading dough, with stunning painted decorations that extend to the interior, while most other dough bowls are plain inside. The wear of years of heavy use—even to a sizeable chunk missing from its rim, which no attempt has been made to repair beyond a stabilizing thong—seems to whisper of its untold past.

So off I went to the books to learn that bread-baking with wheat and yeast was only adopted in the pueblos in the eighteenth century, although the Spanish introduced wheat to the New World long before. Commercial metal tubs have replaced ceramic dough bowls, but the tradition of bread-making lives on in the pueblos today. In her Santo Domingo home, Diane Bird, archivist at MIAC, prepares big batches of shaped loaves for special occasions. She explained that the decoration of a dough bowl, like the decorative forms of the loaves, brings the nourishment into harmony with the forms of the natural world from which it springs.

She steered me to an album of clippings assembled by the distinguished journalist Charles Lummis (1859–1928) that contained his San Francisco Chronicle article, illustrated with his own photographs, on a ceremony he witnessed at Isleta Pueblo in 1888. He described the loaves prepared over three days in the beehive ovens of the pueblo as “astounding freaks of ingenuity in dough . . . In most things the Pueblo appears imaginative enough, but when it comes to sculpting bread and cakes the inventive talent outdoes the wildest delirium of a French pastry cook.”

In Dwight Lanmon and Francis Harlow’s recent compendium of Acoma ceramics, The Pottery of Acoma Pueblo (Museum of New Mexico Press, 2013), I found “my” dough bowl praised as “one of the handsomest examples,” dating 1800–1820. Even with the museum’s more conservative dating of around 1860, that’s old for a utilitarian bowl! So did its exceptional beauty make it a valued heirloom to be preserved even after it was broken? No indeed, insisted MIAC curator Tony Chavarria, who, with former MIAC director Bruce Bernstein, met with me to help me understand the pot. Once damaged, it would have simply been repurposed to serve for household storage. They led me to the original catalog cards, which revealed that the pot was donated by the poet Witter Bynner (1881–1968), with the notation that he had acquired it at Acoma in the 1920s.

Bruce recalled publishing a photograph taken by Bynner of an Acoma man holding “my” bowl. At the Photo Archives of the Palace of the Governors, I found it to be one of a series featuring the same tall, handsome young man, with whom Bynner was clearly quite taken on his expedition to the then remote pueblo of Acoma. In one portrait photo the man wears a jacket, vest, and scarf that Bruce informed me indicated he was a tribal official, who, as such, would have been called upon to assist in a transaction with a visitor. In a group shot we see him holding the pot, presumably the property of the older woman, which he has brought down the stone steps from the mesa behind. Between them an Anglo woman, whose attire suggests she is one of Bynner’s out-of-town guests, emulates an olla maiden.

Bynner was a literary lion known for leading an openly gay life at the center of Santa Fe’s bohemian art colony, but also an active champion of Indian causes in the 1920s. An avid collector of Native jewelry, he first lent, then donated his collection to the Museum of New Mexico, but I could find no record of an equal enthusiasm for pottery. Did he look on the broken bowl as a poignant souvenir of Acoma’s past? It certainly presents a contrast to the perfect contemporary specimens acquired by curator Kenneth Chapman and published in the same 1927 El Palacio (vol. 22), in which Bynner’s poem “At Acoma” recorded an impression of his visit.

For three decades the bowl was surrounded by Chinese paintings and antiquities in Bynner’s home until he decided, in his last years, to give his collections to museums. He donated the pot to the School of American Research (now School for Advanced Research) in 1957, but Museum of New Mexico curator Bertha Dutton immediately incorporated it into the display at the Hall of Ethnology annex to the museum downtown. Resurfacing at MIAC, it invites us to share its history, passing from use in cooking, then storage, to an object of Anglo poetic sensibility, then ethnological specimen, then historic example of fine craftsmanship and design—and to me, the museum visitor, as an object redolent of its many lives.

Penelope Hunter-Stiebel was a curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Portland Art Museum before settling in Santa Fe.