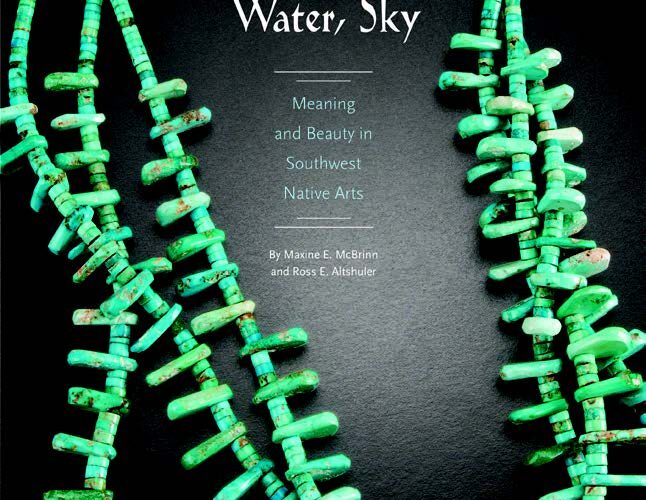

Turquoise, Water, Sky: Meaning and Beauty in Southwest Native Arts

BY MAXINE E. MCBRINN AND ROSS E. ALTSHULER

Attend any gathering — whether ceremonial or civic — of southwestern Native Americans and you will discover that almost everyone, old and young alike, is wearing turquoise jewelry. As in antiquity, turquoise today is important to the region’s cultures for more than just its intrinsic beauty.

In fact, worldwide, wherever it is used and valued, the color of turquoise is compared to the color of the sky and water. The Zuni word for turquoise can be translated as “sky stone”; in Tibet, the sky is sometimes called “the turquoise of Heaven”; and the Mesoamerican deity, Quetzalcoatl (whose image is often portrayed in blues, greens, and turquoise), was associated with fertility, the rainy season, wind, and the sky. Furthermore, for centuries the most desirable Persian turquoise was a clear, pale blue stone with no visible matrix—a color we call “sky-blue.”

Turquoise’s allusion to the sky is obvious, but the stronger symbolism of the stone in the Southwest is to water, a scarce but essential resource. Turquoise has an almost poetic connection to water. The stone is formed in arid lands by infrequent precipitation flowing through host rock and depositing minerals and salts. It’s fitting that the resulting stone’s color echoes its origin.

Turquoise use (and its association with water) accelerated quickly in the region once Native peoples became more sedentary and farmed foods became the bulk of their diet. The earlier hunters and gatherers depended on native plants and animals already adapted to drought conditions and moved to other areas when their food supply dwindled. Once these Native peoples became farmers, their subsistence depended on cultivating plants that originated in the subtropics of Mexico and required higher levels of moisture, such as corn, beans, and squash; and their first line of defense in dealing with drought—moving—became more difficult. Farming required an investment of weeks, months, and even years of labor that involved preparing fields as well as building houses and communities, an investment that was hard to walk away from. Receiving precipitation at the right time during the growing season became vitally important.

Water and sky work together in creating rain, a union that is personified by the blue-green color of turquoise: blue for sky and green for water. Green turquoise can also symbolize the green of healthy crops once the rains have arrived. For Pueblo people, wearing turquoise can be likened to a prayer for rain, a symbol of deeply desired hopes and wishes. By using turquoise in ceremonies, Native Americans heighten those wishes into formal and profoundly powerful requests. No wonder the stone and its association with water and fertile crops is so important in this dry land.

For the Navajo, turquoise is closely linked to health, safety, and protection. In addition, the stone is associated with the sun, the south, and New Mexico’s Mount Taylor—one of the four sacred mountains that define the Navajo world, retrieved from the flooded underworld at the moment when the Navajo emerged into this world.

In [this book], we discuss how some Pueblo groups and the Navajo—the Native peoples of the Southwest most well known for their jewelry—have incorporated turquoise into objects made for personal use, as well as for sale in the marketplace. Although the groups featured here are famous for their turquoise artistry, many other Native peoples in the Southwest, including the Apache, O’odham, and those of Spanish descent, prize turquoise, wear it, and appreciate the color and what it stands for.

Excerpted from the Museum of New Mexico Press book Turquoise, Water, Sky: Meaning and Beauty in Southwest Native Arts by Maxine E. McBrinn and Ross E. Altshuler. Jacketed softcover, $29.95, 172 pages, 142 color photos, 20 color illustrations.