Those Long Lonesome Roads

BY TOM IRELAND

When I was nineteen I’d heard rumors of a vast continent west of New York City, but the farthest west I’d ever been was Fort Lee, New Jersey. My college buddies and I planned a motorcycle trip to the West Coast, and when they flaked out on me, I decided to go alone. What I experienced along the road that summer was mostly the road—particularly the interstate highway system, originally built to facilitate troop movements in case of foreign invasion but equally convenient for a teenager who was taking his first independent look at the continent. Fifty years later, I still get a crick in my neck when I think of it.

It could have been far worse, and surely had been for many of the immigrants, traders, soldiers, couriers, fortune seekers, and assorted miscreants and lost souls who traveled three of the great trails of the West—El Camino Real, the Santa Fe Trail, and the Old Spanish Trail—celebrated and storied in this issue. As Michael Romero Taylor points out in his overview, all three converged in Santa Fe, a town that has been a hub of long-distance travel for centuries, mainly for business, but in modern times increasingly for pleasure. Historic trail organizations representing each of the three will host “All Trails Lead to Santa Fe,” a meeting of historical minds to be held September 17–20 at the Santa Fe Community Convention Center and the inspiration for this issue of the magazine.

Archaeologists such as Michael Bletzer, who is conducting research at the Piro pueblo of Pilabó, contribute to a slowly emerging picture of what life along the Camino Real was like when European immigrants first made their way (literally) along the Rio Grande corridor. State Historian Rick Hendricks notes that the name “El Camino Real” was commonly used during the colonial era to mean any heavily traveled road, and that the name often cited in published work these days, El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro, absent from colonial documents, was an invention of the Prussian explorer and naturalist Alexander von Humboldt. Nevertheless, the name has stuck: names, like editors, are slaves to convention.

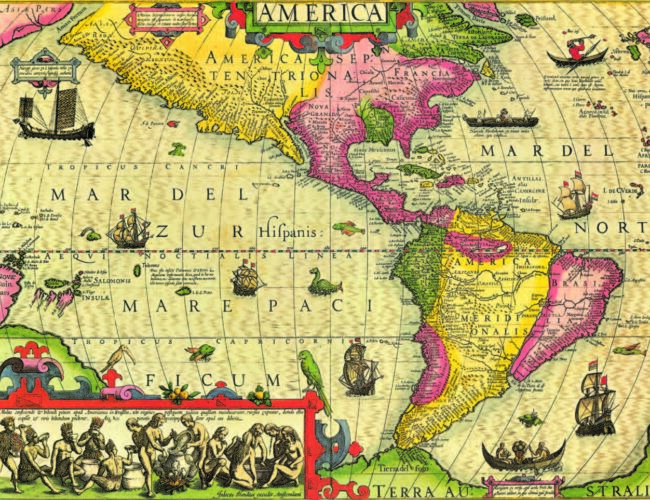

The movement of settlers and their possessions over western trails took place over a long stretch of history, beginning with the advent of Spanish colonists and missionaries in the late 1600s. But photography was slow in coming to the West, partly because in the relatively short time between its invention and the age of railroads so few photographers were willing to risk their health and their fragile equipment, including glass plates for exposures, to the hazards of travel by wagon or coach. Thus, some of the illustrations in this issue have been chosen to convey the spirit of a time before trains and cars became the conventional means of land travel.

The song of the open road still compels the modern traveler to go exploring. Meredith Davidson and Kate Nelson’s search for Mary Colter, architect and designer for the Fred Harvey Company, took them even into the bowels of the earth, where they encountered strange beasts such as “Fredheads” and “Parkitecture.” And Dennis Reinhartz’s romp through the history of mapmaking since New Mexico statehood turned up a spelling of “Albuquerque” that is guaranteed to make editors and designers recoil in horror.

And last: I am extremely lucky, in my capacity as copy editor for the magazine and now as pinch-hitting editor, to have worked with Cynthia Baughman, the previous editor, for the last five years. Her editorial imagination and acumen, her cheerful energy, her forthcoming nature, and her gentle ways never ceased to gratify us, her colleagues. We wish her great happiness and continued good works in the years to come.