Love and War

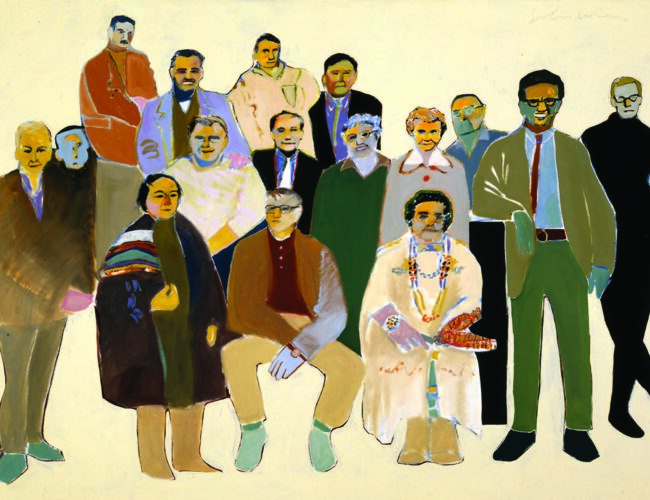

Fritz Scholder, Arts Faculty at the Institute of American Indian Arts at 4:15 pm, 1968. Left to right: (first row) Otelie Loloma, Terry Schubert, Josephine Wapp, Fritz Scholder (standing); (second row) Seymour Tubis, Neil Parsons, Rolland Meinholtz, Lloyd Kiva New, Terry Allen, Kay Wiest, Allan Houser, Michael McCormick; (third row) Ralph Pardington, Leo N. Bushman, James McGrath, Louis Ballard. Oil on canvas, 54 ½ × 71 ½ in. Collection of the New Mexico Museum of Art. Gift of Fritz Scholder, 1968 (2271.23P). Photograph by Blair Clark © Fritz Scholder Estate.

Fritz Scholder, Arts Faculty at the Institute of American Indian Arts at 4:15 pm, 1968. Left to right: (first row) Otelie Loloma, Terry Schubert, Josephine Wapp, Fritz Scholder (standing); (second row) Seymour Tubis, Neil Parsons, Rolland Meinholtz, Lloyd Kiva New, Terry Allen, Kay Wiest, Allan Houser, Michael McCormick; (third row) Ralph Pardington, Leo N. Bushman, James McGrath, Louis Ballard. Oil on canvas, 54 ½ × 71 ½ in. Collection of the New Mexico Museum of Art. Gift of Fritz Scholder, 1968 (2271.23P). Photograph by Blair Clark © Fritz Scholder Estate.

BY TOM IRELAND

When the American Academy of Poets made April National Poetry Month, they must have had T. S. Eliot’s poem The Waste Land in mind (“April is the cruellest month”). During April we celebrate poetry as practiced not only by career poets but also by the man and woman on the street, in the American vernacular. Last summer, two artists, Edie Tsong and Michael Lorenzo Lopez, collaborated in Love Letter to the World, in which passersby at The PASEO, an arts festival in Taos, were recruited on the spot to write love letters to whomever or whatever their hearts desired. A few of those letter-poems are transcribed here in all their raw angst, tenderness, and unstudied grace.

“Make love, not war,” the rallying cry of the 1960s, sounds quaint if not naïve these days. The more the world needs love, the more it cries out for blood. Is the world really becoming more violent, or is it that news of violence reaches us so much more reliably? And to what extent is mass violence encouraged by the publicity that the news so reliably provides, for free?

During the Pueblo Revolt, in 1680, violence of various kinds on the part of the Spanish authorities against the Native population was met with violence. Depending on where you’re coming from, Po’pay’s knotted cords, sent out to Pueblo leaders to coordinate the rebellion, might be perceived as brilliant innovation—the social media of the time—or as the paraphernalia of a terrorist enclave.

We eat our Frito pies in the Santa Fe Plaza just a few feet above remnants of the revolt, which two Pueblo writers, Joe S. Sando and Herman Agoyo, pointedly called “the first American revolution.” Before the Plaza Bandstand was built, workers from the Office of Archaeological Studies dug into a depositional layer subsequently dated in the lab to the late seventeenth century. Some of the artifacts they found buried in that layer appeared to be remnants of a battle, maybe even the one in August 1680 in which Governor Antonio de Otermín and his colony held out in the casas reales (the Palace of the Governors), suffering from thirst and fearing for their lives, against an onslaught of Pueblo and Apache warriors before retreating to El Paso del Norte.

What the archaeologists found might not impress anyone but another archaeologist: a couple of musket balls that had been fired and looked as if they’d struck something hard on impact (human bone?); corroded horseshoe nails; a similarly corroded, nearly indistinguishable tip of a metal knife or sword. What’s remarkable about these discoveries is not so much the objects themselves as their promise that additional evidence of this historic event still exists, right there under our feet.

Jason Shapiro, formerly a lawyer, discovered a fascination with archaeology and went on to publish comprehensive studies of Arroyo Hondo Pueblo and other sites in and around Santa Fe. In this issue’s Perspective, he writes that in writing the history of the Pueblo Revolt, it’s necessary to consider the “agency” of Indian participation and to guard against portraying those who rebelled against Spanish domination, as well as those who didn’t, as mere victims of a historical moment with few or no choices available to them. As an editor, I’ve noticed that writers, perhaps unconsciously, tend to write that “the Pueblos,” “the Israelis,” or “the Republicans,” for example, did this or that, when they mean that “Pueblos,” “Israelis,” or “Republicans” did those things. The point is that some did, and some didn’t. Students of history are lucky to have many and various voices to help them decide who did what—and lucky, too, that those voices are often contradictory.