O Catalog! My Catalog!

BY KATE NELSON

Chances are you didn’t notice the seismic shift on September 30, 2015. I did, but only because I happened to be standing in the New Mexico History Museum’s Fray Angélico Chávez History Library. Its full force nearly buckled my knees.

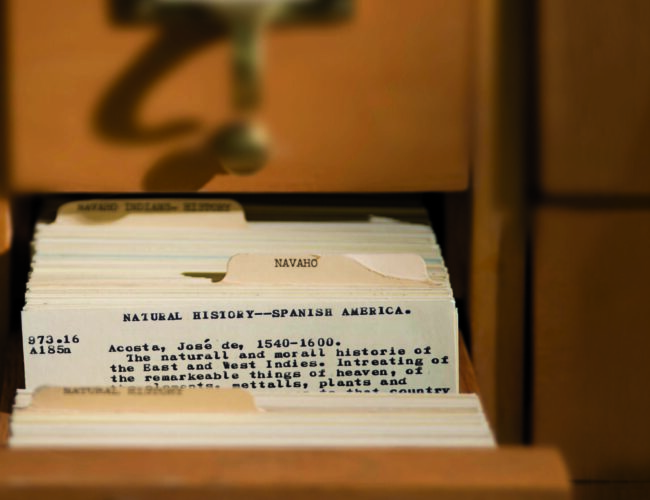

“See these?” Librarian Patricia Hewitt asked, waving a narrow stack of cards at me. “These are the last cards we’ll ever get for the card catalog. The company that makes them is never going to print them again.”

No more card catalog? The news hit me like a fall from a rolling step stool. I was, after all, the pre-internet high school dorkologist who spent nearly every weekend at one public library or another. It wasn’t that I had that much homework. I just loved the adventure. Beyond my teenage comprehension, between the siren song of those sleek maple drawers and the towers of books in the stacks, lay unexplored worlds. I chose random topics or authors, then merrily finger-walked to whatever other offerings caught my eye. Using each card’s Dewey Decimal clues, I tracked down pools of literary treasures, immersing myself over and over.

“We’re probably the last library in Santa Fe still getting these,” Hewitt said, “maybe in New Mexico.”

At that moment, I heard the melody of an elegy stir within me. For the sake of those few who hang on to these shards of 3-by-5-inch salvation, for the last of the breed, let this story be that song.

For all the ways that the imminent death of the card catalog filled me with anxious nostalgia (file that between my fears of airplanes and automobiles), it’s worth noting that card catalogs had a relatively short shelf life—compared to, say, movable type.

Until books could be reliably mass-produced, few people owned enough of them to bother with a cohesive system for what was what and where to find it. The first means of doing so were large book catalogs with index-like pages filled with columns of listings. The system’s main drawback was that whenever you obtained a new book, you had to sandwich a handwritten note onto the proper page’s margin. As new books flooded in, you can imagine the mess.

The late eighteenth century hinted a future solution. During the French Revolution, the government seized all the books it could. It then ordered an inventory, but didn’t have paper for it. So catalogers took decks of playing cards and wrote each book’s information on the blank backs. Sadly, their system didn’t catch on, and the catalog books persisted for another fifty years or so.

By the 1870s, libraries in America and Britain had adopted the old French wisdom, aided by one Melvil Dewey (yes, of decimal fame), who built a business of selling cards and, eventually, pretty cabinets to hold them. Dewey’s system of assigning numbers to books wasn’t—and still isn’t—universally shared by libraries, creating yet another convolution in the cataloger’s rules-heavy history. (A library without arcane filing systems has yet to be found.)

In the old days, one of those rules banned pen names. You want to read everything by Mark Twain? Look under Samuel Langhorne Clemens. That rule eventually changed, along with many others. In fact, they changed dramatically at least three times in the twentieth century, requiring librarians to pull every old card and either edit it or retype it.

Space constraints could also force a massive relocation. Hewitt has been with the library since June 2008 and estimates she’s shifted the shelf list (the cards that show where books actually live on the shelves) at least four times.

“It’s tight,” she said. “It’s very tight. It takes up some room.”

Think about this: In those old days, each book didn’t just get a card, but a set of cards. A title card. An author card. As many subject cards as seemed appropriate. And you needed furniture for each kind of catalog. With about 40,000 books, 6,000 maps, and oodles of newspapers, magazines, and documents in the Chávez Library collection, you’re talking about a lot of drawers filled with a lot of cards.

Where did those cards come from? By the early twentieth century, standardized catalog systems were well on their way, but cards still had to be pounded out on typewriters until the Library of Congress and library support companies began selling ready-made card sets. That helped fill up the catalogs, but libraries still didn’t have a ready way to know whether some other library might have materials that their patrons needed.

In the late 1960s, the Library of Congress invented machine-readable cataloging, or MARC, which produced the first companion print-and-digital records. Now libraries could both share their records and reduce the duplication of time-consuming cataloging efforts. Using one of those old dial-up, screechy-modem computers, librarians and their patrons could tap into a database and find out which library held what. It was, in essence, the dawn of the information age by way of the first online library catalog, although for most of us, “online” was just a futuristic promise.

We didn’t have desktop computers, iPhones, or Google. For once, technology had leapt ahead of a problem. Still, libraries began adapting and slowly built their nowrobust databases.

In 1990 the Chávez Library slimmed down its paper-card requests to one shelf-list card set, solely for staff use. The public catalog fell idle. It was part of a switch that saw all four Museum of New Mexico libraries join the State Library’s SALSA consortium, which contracted with the Online Computer Library Center to provide paper and digitized cataloging options. Every other SALSA member opted for the electronic version. Hewitt speculates that the breadth of the Chávez collection spoke to its need for hard-copy duplication.

Soon, library patrons lost their access to up-to-date card catalogs, but they gained a spot at computer terminals. I remember the switch in my local library. I didn’t like it. The stand-up kiosks didn’t invite rummaging around. The answers popped up in a flash. I found precisely the book I wanted and no others. Some of the magic was gone.

Meanwhile, libraries engaged in “retrospective conversion”— digitizing even their older books and tossing first the paper, then the furniture. Hewitt estimates the Chávez Library has finished 90 percent of that work, hence its continued reliance on paper.

“That little card,” Hewitt said, “is doing a multitude of things that the user doesn’t stop to think about. It’s telling you what we have, so it’s an inventory. But it distinguishes similar items from one another—Hamlet the play versus Hamlet the movie. It collocates items. If you want every version of Hamlet or all the Harry Potter books, it brings them together. So it differentiates and combines. It lets you make a meaningful choice, which Google doesn’t do.

“As much as I love Google, it gives you everything with the word you’re searching for. Who Moved My Cheese? isn’t about cheese. And The Basketball Diaries isn’t about basketball.” Even so, she acknowledged that card catalogs could “also be very unforgiving.” Unlike online catalogs, they lack a keyword search. If you want everything on Georgia O’Keeffe, but leave out that pesky second F, the card catalog won’t correct you. Online catalogs will.

The final cards Hewitt received helped her polish off a cataloging project for the library’s massive maps collection. The work took three years of her effort, plus that of several contract workers. A card on top of one of the final stacks held a message with a graveyard shiver: “CATALOG CARD END OF LIFE.”

Someday, the Chávez Library will likely throw out all evidence of its paper past and join its comrades in web land. How lonely is it in analog land? Are any other loyalists reluctantly inching toward their dates with destiny? The New Mexico Library Association sent a query to its members on my behalf. The answers comprised a trickle.

Bradley Carrington of the State Library said he keeps a catalog solely for older government documents, at least until they’re retrospectively converted. The Roswell Museum and Art Center Research Library keeps its paper catalog as a rainy-day backup. (Power outages do happen, after all.) The Clayton Public Library hasn’t gone digital, but hopes to someday.

Libraries that have switched sometimes find inventive uses for the leftover catalog cases. The Carlsbad Public Library gave one to the Carlsbad Museum & Art Center to hold potsherds. Others in New Mexico use them for shareable seed packets. Pat Hodapp, director of Santa Fe Public Libraries, uses two twelve-drawer catalogs for a coffee table.

By the time she joined the museum, Hewitt was so accustomed to digitized records that she wondered if she had entered a time warp—one she soon grew to love. When the Online Computer Library Center announced last summer that it would soon cease printing cards, she went into mourning. “The cards have character to them,” she said. “I think some people really love to touch something. And there’s a bit of serendipity in flipping through them. You see something you wouldn’t necessarily find. If you’re browsing, you might find something near where you’re looking that catches your eye. Now we just have to live with the cold computer.”

Kate Nelson adores the New Mexico Rail Runner’s Quiet Car for helping her plow through stacks of books during her commute. A Placitas resident, she manages marketing and public relations for the New Mexico History Museum/Palace of the Governors. She is an award-winning journalist and wrote the biography Helen Hardin: A Straight Line Curved (Little Standing Spruce Publishing, 2012).