Drawn to Truth

Ricardo Caté’s Humor Knows No Borders – or Bounds

BY LES DALY

“ALL I WANT IS TO BE FUNNY, ” says Ricardo Caté. Well, maybe. Caté is the country’s only American Indian newspaper cartoonist. Six days a week his drawings, wryly titled Without Reservations, crown the comics page of the Santa Fe New Mexican.

And he is funny, often in a sly, quirky, or poignant way. Subtle, seldom. Sometimes he is sharp, with an arrow he flakes to tickle, but an arrow all the same. According to the editors, Without Reservations is easily the most popular comic feature they print.

Funny, sure, but Caté’s got a lot on his mind. He is trying to tie together on the same page two cultures, Indian and White, that have seldom been on the same page throughout history. “It’s a trick and a half,” he says.

His work has appeared in the New Mexican since 2006. In close to four thousand drawings, he has fathered and raised two principal cartoon characters who reveal how those cultures have endured each other and continue to live in their own worlds, side by side if not together.

There is, first of all, The Chief. He wears a richly feathered war bonnet. He is shirtless, modestly potbellied, and clad in traditional leather pants, a loin cloth, and moccasins. He is a laugh-worthy devil of resistance and resignation.

There is some reason to think The Chief is Caté’s alter ego, although Caté demurs on that thought.

Then there is The General. He is in full blue cavalry uniform, with golden hair cascading from beneath his tall army hat, thick golden eyebrows, and a thicker golden mustache. Any schoolchild would recognize George Armstrong Custer. Caté sets the record straight. “No. He is not Custer. He is the entire dominant White culture.”

CATÉ HAS DEVELOPED a unique, veiled look for these characters. The Chief’s warbonnet always covers his eyes. The black hair, always with a single feather, of the Indian supporting cast flows over their foreheads and covers their eyes, too, ending in braids. The General’s brows and mustache hide his eyes and mouth, which never moves. It is a simple distinctive effect that gives Caté expressive freedom and gives the reader’s imagination a part to play. The women and children who appear occasionally have dot-like eyes that make them seem slightly bewildered. “I don’t often put them in there because I have no authority on how women act or talk,” claims Caté, “so I have a hard time knowing what they would say.” Never mind that he is fifty-two years old and has three children: Eddie, twenty-two; Amber, nineteen; and Nicolette, eighteen. And around him is usually a wide and varied extended family that fills his home with a dozen or so women, men, and children of all ages.

“This place is like a shelter,” he remarks cheerfully. “It’s pretty small and maybe crowded in here, but I welcome everybody. It’s kind of cool. I have these great plans to have a house, a white picket fence and everything. Just like everyone else.”

He was born and now lives in Kewa Pueblo, also known as Santo Domingo Pueblo, south of Santa Fe. The community, or some of it, recently decided to change its name from the Spanish designated Santo Domingo to the Indian Kewa, as some other New Mexican pueblos have done. Not everyone in town agreed, it turned out. “We might have handled it a little better,” Caté says laconically. The pueblo presents both names, and signage to mismatch.

I reached Kewa Pueblo by turning off I-25 at the sign that says Santo Domingo Pueblo. A young fellow paused while sweeping the gravel street to help me find Caté. He pointed generally north. “Go back to that other street and turn left and it’s over there, beyond,” he offered. A woman in a black pickup truck happened by. She said, “Go up the road about a quarter-mile. You can’t miss it; he’s got a cowboy on the wall.” A couple of old-timers at the post office suggested, “Take that road to the right a-ways, then you’ll see another road on the right. That’ll be it.” After a while, the woman in the pickup appeared again, and with a laugh said, “Follow me.” She led me a quarter-mile or so back up the road and into a grassy dirt track, right to the door, waved, and drove off, probably still laughing.

PAINTED ON THE front wall of Caté’s long double-wide trailer was the promised cowboy, or at least a giant Dallas Cowboys football helmet.

“I started it one day, and it got bigger and bigger and then there it was,” Caté later explained without explanation.

Ruminatively but without hesitation he ticks off some of the simmering subjects that bother him while being funny: “dominant culture,” “frustration,” “irony,” “Whites, a formidable foe,” “Indians, forgotten or ignored,” “immigration.” And that’s before he gets to Indian gambling, education, and frybread. It would be easier just to be funny.

Caté uses the terms Indian and Native interchangeably—“Indian maybe 95 percent of the time when I’m talking. The Whites use Native more than the Indians do.”

But he uses the term “dominant culture” often, and it is packed with meaning. Whites in America almost never hear it. They generally wear their dominant culture role unconsciously, as if they were made for it. The way Caté pronounces the word “dominant,” it can sound like a drum; not a war drum exactly, but a steady, relentlessly beating reminder that has hammered on every Native generation for five hundred years. “The dominant culture is everywhere. You can’t escape it,” he observes. “It’s not really negative, it is just a formidable foe. The dominant culture just reminds me that there is this force that I have to adapt to and make my way through while remaining myself.”

IN CONVERSATION HE doesn’t speak in jokes. He talks softly, reflectively, and with determination. He often refers to his father’s strategy for coping with the Indians’ situation. “‘You’ve been dealt this deck of cards,’ he used to say; ‘what’re you going to do with them? You know everything about White people and they know nothing about you. That’s your weapon. You don’t dwell in the past; you go to change the world.’

“So I don’t say, ‘Oh, I’m here because the White people did this to us.’ I’m just here. We’re so busy struggling to move forward. And I’m trying to make the best of things.”

His art and his talent and his special point of view are his aces in the cards he’s been dealt. “I know I have this cartoon, but I don’t speak for everyone, just for myself. I want people in the dominant culture to read it so they at least get a glimpse of our world, how we think, how we act. How funny we are.” And, after a short pause, “That we’re here.”

He concedes that when he began as a cartoonist, he expressed a lot of anger about the history, and the present, and the indignities that Natives often experience in their encounters with Whites.

“Since then, I tweaked it and I’m holding back a little bit now. I’m going more to be funny, but somewhere there’s still that feeling inside the character.”

He rejects the stereotype of the stoic Indian. He enjoys the smiles and even laughter he can produce. (Characteristically, Whites laugh outright, he observes; Natives laugh behind their hands, often at Whites: “They all look alike.”) He recalls his grandmother telling him, “Don’t be smiling all the time.” He was, she scolded, supposed to be more stoic. “But I’m not Iron Eyes Cody. I’m funny.”

His natural humor and unnatural stoicism noticeably recede when he mentions what he sees as a personal responsibility beyond cartooning. This is the small but direct role he has played in education on the reservation. It is one that gives him much satisfaction.

Caté’s life trail has included school in Colorado, college in Kansas, a couple of years in the Marine Corps that took him to Japan and Australia—“It’s a pretty cool world out there”—and dealing cards in the pit of a tribal casino. There were some diversions along the way. But back in his hometown pueblo, he worked hard teaching social studies to Indian students trying for a GED high school credential. Sometimes he held class around his kitchen table. Listening to Caté on youngsters and education, it’s clear that his experiences and, above all, his demeanor make him one of those “teachers who make a difference.” He offers, unsolicited with something between pride and wonder, that in one nine-month period, thirty-two of his students earned their GED.

“Teaching is my biggest personal achievement,” he confides. “Any kid I take in, I always hope they will some time help others, and help themselves.” He urges his students, and his own children, to “go out and see the world…and then come back. That’s what my dad told me.” That is what he did.

Caté’s current drawing board is essentially wherever the ideas find him: at home, in the offices of the New Mexican, at Tia Sophia’s, a hospitable New Mexican restaurant just off the plaza in Santa Fe. He sketches black-line drawings until he accumulates enough for a six-day week at the top of the comics page. In a kind of paint-by-the numbers process, the newspaper sends the drawings to an outfit in Florida, which follows his color instructions.

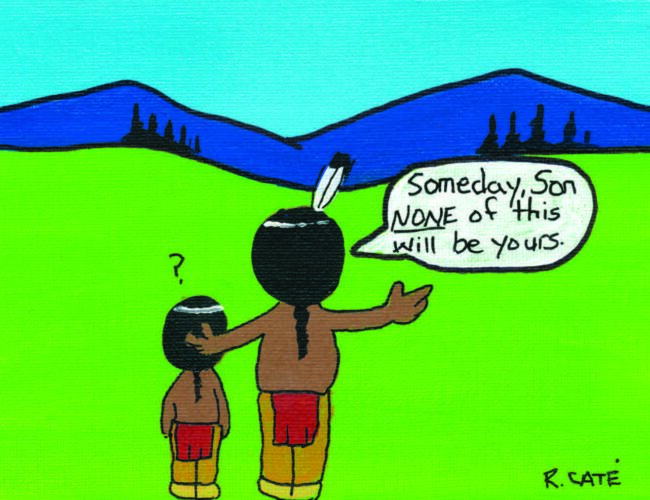

He enjoys taking a common phrase or cliché and giving it a new, Native twist.

EARLIER THIS YEAR, the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture on Museum Hill in Santa Fe presented an impressive and thought-provoking exhibition entitled Into the Future: Culture Power in Native American Art. One element dealt with the concept of “culture jamming”—as the exhibition defined it, “in artistic practice, a form of activism that challenges the authority of mass culture by hijacking popular icons and visual imagery. Culture jammers are tricksters who provoke disorder and inspire change.”

Enter Caté the trickster and his contribution to the exhibition.

One of Caté’s favorite cartoons similarly depicts The General and The Chief, football rivals, too, eyeing each other. The Chief’s jersey says “Cowboys.” The General’s shirt declares “Redskins”.

Symbols like the Redskins and Wahoo are perennial irritants to some Natives. But in truth, as Caté indicated, on the list of irritants they cope with every day, sports-team names probably don’t make the playoffs.

New Mexico, of course, has experienced a prolonged parade of “dominant cultures,” beginning first with the Spanish, followed by the Mexicans, then the Americans, and now, Caté sometimes playfully points out, the tourists. He classifies them all as Europeans or Whites.

“America has a short-term memory,” he complains. “Or they don’t want to remember. So every once in a while I’ll come up with a cartoon just to remind them.” The Spanish conquistadors play recurring roles. In one comic, a puzzled Indian in his loincloth watches the arrival of Coronado on horseback. First come the friars bearing omnipotent crosses. Then, Coronado, encased in armor and wielding a sword and with his horse, also heavily protected by metal and leather. He is followed by a mass of soldiers and cannon reaching to the far edge of the cartoon. To the lone Indian, Coronado says, “We come in peace.”

Everyone knows what happened after that, remarks Caté. “They stepped on people’s toes, to put it lightly. Way, way lightly. They, the Whites, just have to be reminded this land came at a price.”

Despite his humor, and even his encouraged stoicism, Caté speaks fiercely about his concerns that the tragic Native history is seldom given due respect or even recognition. “What happened at Sand Creek? Or Wounded Knee? What about the genocide?” he asks rhetorically. “People say, ‘Well, get over it.’ I hate that. Because those same people are telling me, ‘Remember 9/11.’”

Many cartoonists secretly feel that if they haven’t offended someone, somewhere, they haven’t been working hard enough. Caté sets a more peaceable task for himself. “It is really challenging to draw this cartoon,” he admits. “How are my people going to feel about it? How are non-Natives going to feel about it? If I wanted to I could offend the hell out of a lot of people. I could get hate mail. I don’t want to do that. I want people to read this. I just want to be funny,” he insists.

But he can also be edgy, and sometimes over-the-edgy. Has either side been offended? “Just the dominant side,” he replies. “So far I’ve had no complaints from our side at all. I don’t get a critique from Indians.”

A few years ago he stirred up a small storm among his White readers for a cartoon that alluded to scalping. He apologized, more or less, with a cartoon that showed two coiffed Whites buried in the desert up to their necks with a promise that said, “Non-native captives will no longer be scalped in this cartoon panel. Instead, they will be combed and permed.”

When a cartoon chides Indians about their attitudes or something in their lifestyles, he can get complaints from White readers accusing him of racism.

“I write back and tell them I’m Indian and they say, ‘Oh well, that’s OK then.’” He goes on, “The part that makes me feel good is that it never even occurred to them that a Native would be drawing this.”

He has tried on a number of occasions to get his cartoons syndicated to gain wider visibility in other newspapers and magazines. He is caught in a kind of circular maze. The Native population—about five million including Alaskan Indians—is relatively small, and newspapers are generally not readily accessible or able to afford syndicated cartoons. At the same time, the dominant culture whom he is trying to inform about Native issues and humor—and existence—isn’t really aware of the whole issue at all, and doesn’t demonstrate much interest in Indians or in reading more about America’s cultural conflicts, even humorously.

“The syndicates have told me they aren’t ready for this kind of thing yet,” he relates. “I tell them they’ve been ready for 524 years.” Caté isn’t exactly waiting for the syndicates to get ready. He is irrepressible and relies regularly on certain features and foibles of Native life to prod Indians gently, or sometimes not so gently. Frybread addiction, for instance, is his cartoon staff of life.

Frybread, for the unfortunate uninitiated, is a Native specialty. Like much of their life today, it was born in a painful past, the forced nineteenthcentury migration from Navajo lands courtesy of Kit Carson and the US Cavalry. The simple recipe comes from the sparse supplies given to the Natives by the army: flour, water, salt, powdered milk, baking powder, all mixed into a ball, rolled out, and plunged into a deep pool of cooking oil, traditionally lard, for serious frying. It emerges in various sizes, browned and bubbled and saturated. It is consumed straight or flavored with honey or powdered sugar or loaded with an array of toppings and folded like a taco. It’s been calculated that a single slab of frybread can deliver 700 calories, including 27 grams of fat. It is heart-stoppingly delicious. If it weren’t so available as a subject to return to regularly, what would Caté do without it? “Probably lose a lot of weight.”

To the suggestion that this big, heavy, deep-fried delicacy may over time harm more Indians than Custer ever thought of, Caté muses, “There’s another cartoon in there.”

He is also no fan of Native gambling casinos, where he worked for a while. Theoretically, the casinos have been established, perhaps as the Natives’ revenge, to make money from tourists and wealthy Whites. Caté says casinos throughout the country, particularly those far from big cities, as in New Mexico, are barely profitable, and therefore the payout to many tribes is less than hoped for. Worse, economically stressed Natives are repetitive visitors, seeking a diversion or a dream. He feels deeply that the cards are stacked against them. In a related comic, a Native father comforts a weeping child, saying, “I know how much you miss Mommy, son, but she is in a better place.” The second half of the cartoon shows the mother pounding frantically on a nickel slot machine.

In 2012, Gibbs Smith published a paperback book of his cartoons entitled Without Reservations, and he posts many on his Facebook page. Both tend to concentrate on Native life. Caté’s comics-page cartoons, on the other hand, focus more often on the historic and enduring friction—humorously presented, to be sure—between The Chief and The General, the Indians and the dominant White culture.

And Ricardo Caté’s own counteroffer, without many reservations? Be funny, no matter what. And he is.

Les Daly has written for Smithsonian, the Atlantic, the New York Times, and other publications.

THE YEAR OF COMING TOGETHER

In North Dakota, this has been a year of oil and pipelines. It has also been a year of water and land and burial grounds sacred to the Sioux Indians. And a reminder once again that oil and water, Indians and White power, do not easily mix.

For Richard Caté, there in late summer at the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation, it has been a year of “coming together,” a momentous time when, he remarks with awe, “I have never seen so many tribes in one place.”

After dropping off his daughter, Nicolette, for her freshman year at Fort Lewis College in Durango, Colorado, Caté had decided suddenly to participate in the faraway dispute taking place dramatically over another new pipeline. The siren of Native solidarity and the quest for recognition can overpower any GPS. “I turned left toward North Dakota instead of right toward home in New Mexico,” he says simply.

He announced on his Facebook page that he was on the way and solicited donations from his followers. He quickly collected about six or seven hundred dollars, which he converted into a pickup-load of diapers, bologna, hot dogs, ice to keep it, “and all the Spam Walmart had on its shelves.”

When he first arrived, he said, about 120 tribes from all over the country had assembled, a number that reportedly soon exceeded 200. They were all there to support the Standing Rock Sioux as an oil pipeline company, with government backing, sought to burrow under the Missouri River at the precise point where it crosses the reservation land.

The authorities labeled the Indians “protesters.” The Indians quickly labeled themselves “protectors,” maintaining they were “protecting the water and Mother Earth who can’t speak for herself.”

Caté was “overwhelmed,” he says, “at the significance of this whole thing, of all these tribes coming together to help this one tribe out.

“The Crow Nation and the Sioux have never gotten along; maybe the last time they did was at the battle of Little Big Horn,” he reflects. “And here the two chiefs embraced. Oh, man, that was nice. It was significant. It was very moving.”

He drew cartoons as the situation evolved and posted them on his website. He bought materials and canvases in Bismark to produce paintings, and he gave the children in camp lessons in art and on how to make banners. He planned to stay a few days, but spent two weeks, sleeping mostly in his twenty-year-old GMC pickup, which had barely made it to Standing Rock.

The argument over oil and the preservation of pure Missouri water and the sanctity of the land will probably continue, no matter how or if each side advances or retreats periodically, as long as the campaign lasts. Caté, though, is passionate about the possibility that the whole scene may have an even greater, long-term importance.

“There is a new momentum going on, with all these tribes here,” he says. “We’re not going to take it any more, from anybody. This is like Little Big Horn all over again.” He says he’ll keep his favorite cartoon character, The Chief, on the job to maintain that momentum in the campaign for Indian recognition. “Sometimes I have to go take care of business,” he says, “but The Chief, he’s still there.”

Caté declares, “Once you put faces on us, as artists, actors, singers, writers, cartoonists, then you’ll stop thinking about us as mascots. . . . Everything I do is to let people know that we’re still here, and I’m maybe just as smart as you are.” And, after a sly smile, “In fact, maybe even smarter if I can get you to laugh at yourself in my cartoons.” — L. D.