Defining Moments

In 1919, a Native art show at Santa Fe’s Museum of Art just happened to revolutionize American modernism.

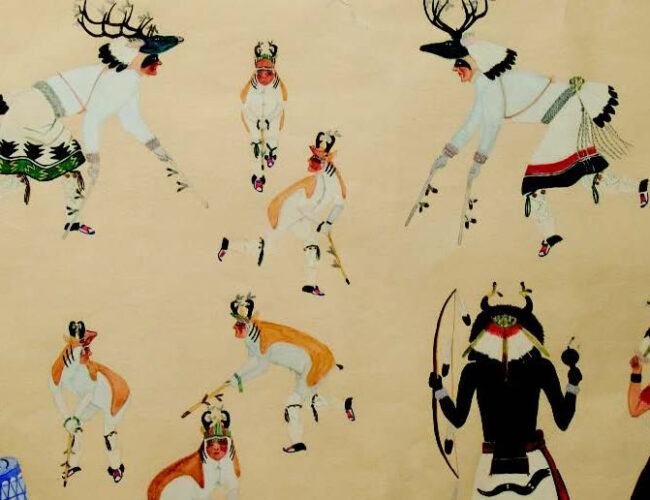

Velino Shije Herrera (Zia),Buffalo Dance, ca. 1918. Gift of Elizabeth DeHuff. Watercolor on paper. Collection of the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture (MIAC

Velino Shije Herrera (Zia),Buffalo Dance, ca. 1918. Gift of Elizabeth DeHuff. Watercolor on paper. Collection of the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture (MIAC

By BESS MURPHY

In March of 1919, the New Mexico Art Museum (now the Museum of Art) opened the exhibition Dance and Ceremonial Drawings, with work by students in Elizabeth DeHuff’s informal art classes at the Santa Fe Indian School. This exhibition marked a pivotal moment in the reception of American Indian painting as fine art, in part because the recently opened New Mexico Art Museum—the monolith of Santa Fe style, the first white-cube space in the Southwest’s capital of art—hosted this small exhibition. Edgar Lee Hewett, the first director of the Museum of New Mexico, radically expanded the purview of that organization by establishing the art museum, which worked for decades in conjunction with the Palace of the Governors and the School for American Research (now the School for Advanced Research) to cement the role of Santa Fe as a cultural destination. In 1917, two years before Dance and Ceremonial Drawings opened, when the New Mexico Art Museum held its first exhibition, the New York–based Current Opinion heralded it as “an American art museum that is completely American—American in its origin and American in its aims.”

The museum’s groundbreaking 1917 exhibition gathered a significant roster of leading American artists, including Robert Henri, George Bellows, Ernest Blumenschein, and Joseph Henry Sharp. Works by student artists in Dance and Ceremonial Drawings were displayed at this new institution, in a space christened by early-twentieth-century art stars. This reveals the museum’s vision of a modernism full of complexity and often incongruous cultural influences, one in which American Indian painting was suddenly seen as modern American art rather than exotic craft or document.

Other, later exhibitions of Indian art that took place in major American cosmopolitan centers such as Chicago, New York, and San Francisco often overshadowed the Santa Fe Indian School exhibition. I found little detailed exhibition documentation from this period in the Museum of Art’s archives. The exhibition title mentions no artist names, and El Palacio covered it with a brief, if effusive, paragraph, also devoid of artists’ names. However, it must be taken into consideration that this small, but catalytic, show was held at a regional outpost rather than in a large city, and focused solely on Indian artists’ watercolor paintings, an art form which had only begun to gain national attention.

El Palacio’s discussion of the exhibition, published in the April 7, 1919 issue was limited to a few short lines that, nevertheless, promulgated widespread views held by Anglo artists and collectors at the time on the meaning, origin, and power of Indian art in general: “The symbols and emblems are correct to the smallest detail although drawn from memory rather than from living models. The entire exhibit seems to prove that with the Pueblo Indian art is racial rather than individual and the beautiful results are obtained if the Indian is given free scope to express himself.” The wider implication is that Native American art-making was beginning to be recognized as natural, intrinsic, and authentic, an expression of art in its purest, communal form. For many white American artists and cultural boosters, it expressed an ideal, American counterpoint to European modernism and its embrace of African and Asian influences.

While collectors and supporters envisioned Indian art as part of a natural cultural and racial identity, the reality was that the paintings in Dance and Ceremonial Drawings had been created under the guidance of DeHuff and intended for an Anglo market. The racial, and racist, framework of this statement confirmed the elevation of Indian painting to the status of art rather than craft, while paradoxically creating a separate and static rubric for assessing such art as always foreign and exotic.

The El Palacio statement helps to situate the exhibition in a broader conversation about what American art should and could look like as the country and world emerged from the shock and horror of the Great War. This conversation was happening not only in the artist studios and salons of New York City, but also in the adobe homes and dusty streets of Santa Fe and Taos. The 1919 exhibition included works by the now renowned early Pueblo painters Fred Kabotie (Hopi), Velino Shije Herrera (Zia), and Otis Polelonema (Hopi), as well as four other, less well-known student artists—Jose Montoya (San Ildefonso), Jose Miguel Martinez (San Ildefonso), Manuel Cruz (San Juan), and Guadalupe Montoya (San Juan). Mabel Dodge Sterne bought the exhibition in its entirety. She had yet to marry Tony Lujan (Luhan) (Taos) but had already committed herself to the indigenous arts and communities of New Mexico.

The paintings in the exhibition would have been similar to those pictured here, which were created in the same years. The ceremonies and dances depicted by Shije Herrera, Kabotie, and Polelonema are scenes drawn from each artist’s memory of life at home. The relatively flat figures are captured mid-movement across the blank backgrounds of the paper. Shije Herrera placed his figures alone on the plane. Kabotie included vegetation. Polelonema situated female figures seated on blankets. These are not arbitrary details, but crucial elements of the ceremony depicted. Similarly, the very absence of background creates a ceremonial space, recalling the pueblo plazas in which all such activities take place.

The degree to which these artists were still learning to manipulate their materials and render faces, bodies, and clothing affirms the works as early pieces from their days as students at the Indian School. Kabotie and Polelonema continued to paint throughout their lives. Polelonema shifted somewhat away from painting as he become increasingly devoted to traditional Hopi practices. Herrera left behind his painting career after a tragic car accident in the 1950s.

This small show of seven young, emerging painters created momentum that would significantly expand the careers of Kabotie, Herrera, and Polelonema. Their creative practices, guided by first DeHuff and then Hewett and their expanding circle of collectors, grew expressively and technically from this starting point. Before the exhibition, DeHuff had invited them to come to her house on the Indian School campus (she was the superintendent’s wife) and paint images of Pueblo life. The arts in general were not permitted as part of the Indian School curriculum, and the federal bureau that managed Indian boarding schools like the one in Santa Fe particularly frowned on images of traditional ceremonies and dances. DeHuff quietly challenged these standards and encouraged her young protégés to paint images of home without instruction in what she saw as non-Native influences such as perspective, shading, or modeling. This early, nonstructured atmosphere had the unexpected outcome of limiting future Native artistic expression for a time, as this particular style became the only acceptable Indian mode of painting.

The museum continued to expand its position in terms of American Indian art, publicly endorsing painting as “authentic,” like pottery and other “traditional” arts. Unlike EuroAmerican fine arts, which were stratified with painting at the top and crafts like pottery and textiles at the bottom, Indian art was rated based on its perceived historic accuracy. Because painting on paper or canvas was not found in historic artifacts, it had not been seen as authentic, and was thus of a lesser value. However, through the continuing display of Native paintings, the museum significantly shifted this hierarchy. In 1920, the year after the exhibition, the museum loaned a selection of Pueblo paintings to the annual exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists in New York. Ashcan School artist and part-time Santa Fe resident John Sloan organized it, further cementing the relationship between these artworks and the American avant-garde.

From this point forward, the museum held multiple exhibitions of Indian art each year, many of them devoted to painting in the increasingly recognizable Pueblo style, with its blank backgrounds, simplified figures, and stylized detailing. In 1920 alone, the museum hosted five shows dedicated to Native American artists, including Alcove exhibitions of student watercolors, the works shown at the 1919 Independent Exhibition, and perhaps most importantly, the July 1920 Exhibit of 17 Pieces by Maria Martinez of San Ildefonso, the museum’s first solo exhibition of a nonwhite artist and the first time that an individual Native artist was listed by name in an exhibition title at this institution. Another exhibition focusing on Native artists as individual makers would not open until 1926, with Awa Tsireh and Julian Martinez: Joint Show of Indian Portraits and Reservation Scenes.

Also in 1920, the museum opened one of its most diverse Fiesta Shows, representing the work of Santa Fe and Taos artists, including paintings by Crescencio Martinez and Awa Tsireh (San Ildefonso) as well as Velino Shije Herrera and Fred Kabotie. These exhibitions kicked off many of these artists’ careers, most of whom continued to create and sell paintings in the stylized Pueblo painting mode. The 1932 Venice Biennale included works by Fred Kabotie; he painted murals for a major 1941 exhibition, Indian Art of the United States, at the Museum of Modern Art. Velino Shije Herrera painted murals for the US Department of the Interior and was awarded the French Ordre des Palmes Académiques in 1954.

The increasing presence of Pueblo artists in the halls, or more specifically the alcoves, of the New Mexico Art Museum evokes an inclusive sensibility that was far ahead of its time. But while Hewett and the museum espoused the much touted open-door policy inspired by Robert Henri, leading to the exhibition of works by a roster of artists both known and emerging in the museum’s frequently rotating alcove spaces, this philosophy did not apply to nonwhite artists. Hewett did not permit Native American artists to add their names to the alcove list and thereby to receive an open gallery space; instead, he and collectors orchestrated their shows. This systematic paternalism and racism marred otherwise progressive practices. This didn’t just impact Native artists. In the first decade of museum exhibitions, not a single show focused on Hispanic or Nuevomexicano arts or artists. Hispanic arts did not explicitly appear in the museum’s listing of exhibitions until September 1927, in the form of the 2nd Annual Prize Competition Exhibition of Spanish Colonial Arts.

Ultimately, within this institution, the presence of Native American artists and the absence of Hispanic artists reflected how widespread the idea of American indigeneity was, as embodied by Native American arts and their progressive political counterparts. The incorporation of Native arts into art with a capital A was a double-edged sword. It created substantial career and creative opportunities for Native artists, but it also instilled a hierarchy within the arts that Native arts leaders such as Lloyd Kiva New, Fritz Scholder, and T. C. Cannon would view a few decades later as assimilationist and stultifying. At the same moment that Anglo museum officials and collectors were telling Native artists what their art should look like in order to be more Indian, non-Native artists such as Marsden Hartley, Arthur Dove, and Stuart Davis were freely replicating Native imagery and styles in their own work.

The restrictions Indian artists faced are indeed troubling today, but it’s important to understand these early exhibitions of Pueblo artists within the New Mexico Art Museum as part of the broader landscape of art in early-twentieth-century America, particularly as this specific institution represented it. The first few decades of the art museum in Santa Fe mirror and even prefigure major trends in this field. The museum created an image of American art that was indeed American in origin in large part through exhibitions that incorporated not just Anglo images of Indians, but also—importantly—Indian depictions of themselves.

At the same moment, the museum recognized other sources of modern art in its definition of fine art. Curators hung Native American art in the same institution that presented Exhibit of Chinese Paintings, which included some works over eight hundred years old; Chinese and Japanese tapestries; batiks from Singapore and Java; an exhibition curated by Dr. Carl E. Guthe on the how Pueblo pottery was made; indigenous weavings from the Southwest and Mexico; and the Loan Exhibit of Photographs of Ancient Sculpture and Plastic Art from the Maya and other pre-Spanish Cultures of Mexico and Central America by Dr. C. Kennedy (Collection of the Peabody Museum), among others. These exhibitions were scattered among numerous other alcove and thematic shows dedicated to the artists who are now emblematic of Anglo art in and of New Mexico: Gustave Baumann, the Taos Society of Artists, Los Cinco Pintores, Olive Rush, Raymond Jonson, and other men and women working in the internationally recognized creative centers of Santa Fe and Taos.

The New Mexico Art Museum often borrowed art and cultural collections from Santa Fe artists and residents for these diverse exhibitions, which began almost immediately after the art museum opened. Anglo artists showing and living in Santa Fe were critically engaged in local and national conversations regarding the multiple modern aesthetic sources driving American art forward. While artists and critics from this period made much of an American art with an American origin, and sought an indigenous voice to propel America away from European models, many artists were also considering the power of visual forms from non-Western cultures. In Santa Fe, Native American art ultimately won out as the most inspiring cultural source, but it did not happen overnight, and this creative exploration played out on the walls of the art museum.

All of this came to fruition in the regional outpost of tiny Santa Fe, setting a precedent for exhibitions that would appear later at other museums across the country. For example, the Museum of Modern Art in New York followed a certain curatorial pattern established in Santa Fe. Santa Fe artists and museum officials had already laid the groundwork for this radical vision of “modern” art, opening up the possibility for an inclusive American art. “That the New Mexico Art Museum put Native and non-Native art together in a museum building was a first act; that they did this long before other institutions shows courage, particularly when Hewett was working to create the reputation of Santa Fe as an art center,” says Bruce Bernstein, author and curator of numerous articles, books, and exhibitions on Pueblo Indian artists. “He was resolute enough to be inclusive in his vision for the museum.” The effects of this on Native and Anglo artists and art history continue to ripple forward.

The young Native student painters who in 1919 presented their images of absent families, communities, and practices to the art public were brave enough to defy fiercely enforced rules at their school in order to maintain and depict a profound connection to their own cultures. That Santa Fe’s art museum not only saw the beauty in the works and their value as descriptions of cultural traditions, but also their significance to art in America, can inspire us all to expand the boundaries of art today.

Bess Murphy is assistant curator at the Ralph T. Coe Foundation for the Arts in Santa Fe and a PhD candidate in art history at the University of Southern California