Palace Intrigue

Deciphering secrets...behind walls and below floors

BY STEPHEN S. POST

In the fall of 2016, the New Mexico History Museum embarked on a preservation project—to remove the existing stucco that covers the building walls surrounding the Palace courtyard. The History Museum staff and preservation team responsible for the work felt anticipation, excitement, and maybe a little trepidation over what new secrets might be revealed by exposing the adobe walls for only the second time in more than one hundred years.

When team members discovered a skeleton key beneath the stucco, our sense of anticipation rose even higher. Perhaps the key was a harbinger of the old secrets we were about to unlock; on the other hand, sometimes a key is just a key. Either way, as project archaeologist my quest required that I review my own experiences and those of my predecessors as we delved into mysteries of what many consider the best known landmark in New Mexico.

As a rule, archaeologists working in the Southwest spend more time looking down than up. However, the Palace is a place where we have to do both to get the full story. Archaeologists who have worked on the Palace know their quest, no matter how well informed, will often follow a much different path than we expected—reminiscent of the Lew Wallace quote, “Every calculation based on experience elsewhere fails in New Mexico.” The upside: those unpredictable walls continue to give us more accurate views of the Palace’s past.

The Palace Becomes a Museum

In 1908 Dr. Edgar Lee Hewett, soon to be director of the new Museum of New Mexico, was conducting archaeological investigations in the southwest Colorado Plateau with a trusted crew that included Jesse Nusbaum. He offered Nusbaum the first position at the new museum as archaeologist-superintendent and photographer. Nusbaum, who was to head up the renovations, wrote that he “had always found the structure of the Palace the most interesting in the Southwest. Its current massive walls evolved over a period of four cultures and withstood the ravages of time very well.” With these thoughts, Nusbaum embarked on remodeling the Palace over the next four years. He knew that bringing the Palace up to his and Hewett’s architectural and aesthetic standards would be challenging. In fact, early on he observed, “For some years the Palace of the Governors had been deteriorating very rapidly. . . . Here was a need to eliminate excrescences, substituting nothing and holding to the natural lines. The venerable building of great historical importance should beyond doubt be preserved in all integrity and perpetuated for all time.”

All previous Palace renovations had focused on repairing the building and making it functional. Until the late nineteenth century, those efforts showed scant regard for the Palace’s historical values. As an archaeologist, Nusbaum approached the building with sensitivity to its importance to New Mexico’s heritage. However, his focus on an idealized eighteenth-century aesthetic distracted him from historic “excrescences” that would fascinate future archaeologists working at the Palace.

As part of a major earthmoving effort aimed at returning the Palace courtyard to its former elevation and to assist the interior remodel, Nusbaum had 2,100 small wagonloads of soil and detritus—1,000 cubic yards—removed from the Palace grounds. In these heaps of earth, he hoped to discover significant Spanish Colonial and Ancestral Puebloan artifacts. According to Nusbaum, “All debris was carefully screened for archaeological values ‘in situ’ and then hauled to wherever fill was requested.” From my work north of the Palace, I estimate that Nusbaum’s crews, following practices of the time, regrettably removed and discarded hundreds of thousands of artifacts, construction materials, and organic specimens and samples not considered worthy of detailed study or long-term curation within the budding museum’s collections. Apparently, finding no whole ceramic pots, complete household or military items, human burials, or intact or recognizable architectural or institutional features, they removed much of the eighteenthcentury Spanish archaeological deposits from the immediate grounds. Preoccupied with the task at hand, Nusbaum focused narrowly on the building and its archaeological, historical, and architectural heritage, not the minutiae of daily life at the Palace’s former occupants.

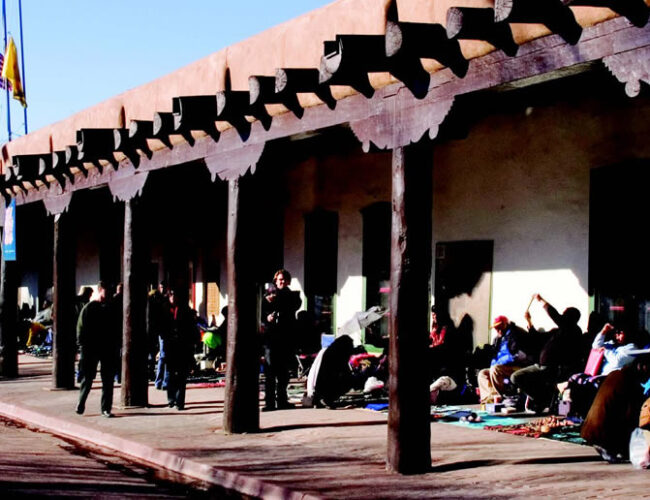

He succeeded. Today, when I walk through the Palace along with its tens of thousands of visitors, I see how the architectural details Nusbaum preserved continue to bring the eighteenth-century building to life. Low doorways with thick, hand-hewn lintels in Rooms, 5, 9, and 11 are typical of Spanish Colonial buildings. A window in the south wall of Room 5 has a small opening that was probably glazed with sheets of selenite, which we often find in archaeological excavations. (Selenite is translucent, allowing light enter otherwise dark rooms.) . When Nusbaum found a hand-carved wooden corbel and post enclosed within the adobe wall in Room 7, he uncovered a key detail of the eighteenthcentury Palace. He selected it as the model for the corbels that now grace the portal on the south side of the Palace facing the plaza. Today, the Palace’s post-and-corbel portal is an architectural icon of Santa Fe style, and I would venture to say the subject of millions of photographs over the last 104 years.

Just What’s Under Those Wood Floors?

As the Palace of the Governors evolved as a museum, numerous renovations and archaeological investigations were conducted in the sixty years between Nusbaum’s work and a major project to install concrete subfloor support beams beneath the sagging floors in Rooms 5, 7, and 8. In the spirit of other renovation projects, the Palace director invited an archaeologist, Cordelia T. Snow, to look below the room floors prior to the construction project. Dedie, as she is known to the multitudes that benefit from her vast knowledge of Palace archaeology and history, was given six weeks for her work. Based on the received and fossilized history of the Palace at that the time, she expected to find evidence of the eighteenth-century Spanish governor’s use of the Palace. Nusbaum had found mostly eighteenth-century architectural remnants, and without contrary information from intervening studies, Snow expected to find much the same. Soon after the work began, she was pleasantly surprised by what she and her crew found. Subsequently, over a period of almost two years, from January 1974 to December 1975, they worked through Rooms 7 and 8, the West Hallway, and Room 5.

Snow and her team began the dig on January 4. They encountered the expected mix of twentieth-century debris, with some earlier pottery sherds and animal bone. When Snow encountered a deep cylindrical pit (Feature 3) filled with the domestic and kitchen debris of a late seventeenth- or early eighteenth-century household, her quest shifted dramatically. Finding one storage pit alone would have been worthy of note, but extraordinarily, she found seven additional storage pits. They contained a unique inventory of Spanish Colonial artifacts and specimens, including unburned foodstuffs such as corn, bean, squash, fruit seeds and pits, wheat grains, and lentils. Europe, New World, and the Far East were represented by majolica, porcelain, brass pins and needles, leather fragments, a brass candlestick, silver and gold galloon (woven trim), buttons, and a double-barred cross. Since the pit contents evoked a prosperous way of life on the Spain’s imperial northern frontier, Snow’s perspective expanded far beyond conventional stories of deprivation and need.

In Room 7 she encountered extra-large foundations of seventeenth-century buildings that suggested the former presence of a building with very high walls or even two stories. As she worked through the other rooms, she found that larger foundations were common under major east–west, weight-bearing walls. Once more, her perception of the building’s history changed, as she imagined a Palace more massive than indicated in previous histories.

Snow then turned her attention to Room 5, where she excavated exploratory test pits below the floor. This revealed adobe-brick floors laid in a diagonal (herringbone) pattern, unlike any previously noted in seventeenth-century New Mexico. In April 1975, the team uncovered the foundations and floor of a large room. The quality of the floors and size of the room suggested it had been used by the governor, and not for storage.

Testimonies from the inquisition and trial of Governor López de Mendizábal and his wife, Doña Teresa Aguilera y Roche, from 1663 to 1665, give an unparalleled account of the Palace’s rooms and their functions and contents. Through these accounts of Governor Mendizábal and his wife’s misfortunes, we learn the Palace had eighteen rooms, including the governor’s residence, a small chapel, servant’s quarters, administrative offices, storerooms, and a jail. This spacious floor plan, with elegant rooms for the governor and his wife, conforms to Snow’s findings and the new vision she was forming of the seventeenth-century Palace.

It didn’t end with Snow’s research setting the current understanding of Palace architectural history on a new course. In Room 5, where her crew uncovered the seventeenth-century floor, they encountered smaller foundations encasing thick, mud-plaster floors that subdivided the larger Spanish room into four smaller rooms containing fire pits, small storage pits, and Native American human remains. She determined that the rooms were definitely not of Spanish making or identity but remnants of the large pueblo built by the successful Puebloan rebels following the expulsion of the Spanish from New Mexico in August 1680. The Palace was not just a symbol of Spanish imperial reach in the New World, but a surviving remnant of a time when Pueblo people and their allies fought for their basic human rights against an increasingly oppressive foreign regime. From the moment Snow brought this long-buried evidence to light, the Palace regained a lost history as a symbol of Puebloan resilience and resistance to the suppression of their people and culture. I doubt this was a story Nusbaum and Hewett expected their museum to tell future visitors.

Secrets of the Palace Backyard

Fast forward twenty-seven years to the planning for construction of the New Mexico History Museum in 2002, which included time and budget for archaeological excavation of the parking lot and alleyway north of the Palace Print Shop and parking lot encircling the footprint of the now-demolished Museum Administration Building (former Elk’s Lodge). In a planning meeting with Tom Wilson, then the director of the Museum of New Mexico, I suggested that the excavation, to be conducted by the museum’s Office of Archaeological Studies, might recover one million artifacts. My half-joking estimate was a significant departure from an earlier History Museum assessment that nothing of importance would be found because the area had been disturbed by twentieth-century urbanization. With a modest research design in hand, I proceeded with a pragmatic estimate that we would make findings somewhere in between the two extremes.

Within the second week of work in October 2002, we found a gold cast ornament or adornment from the seventeenth century, along with tens of thousands of artifacts predating the 1930s, and stratified layers of river-cobble building foundations from seventeenth-, eighteenth-, and nineteenth-century Spanish presidial and US military structures behind the Palace. When our work ended in September 2004, we had recovered over 800,000 artifacts, specimens, and samples, and documented the remains of almost 200 architectural, waste-disposal, food-processing, and demolition features from 350 years of Palace history and 700 years of downtown Santa Fe’s past. I estimated that the area now occupied by the New Mexico History Museum might have yielded more than 16 million artifacts if 100 percent of the area were systematically excavated.

Similar to Dedie Snow’s experience in 1974, the fruits of our labor exceeded all expectations. Perhaps the most compelling and important discovery was the cobble building foundations that we painstakingly exposed and documented. These foundations told a more complete story of the rooms and buildings that likely housed elements of the presidial force from 1716 to 1791. They are minimally mentioned in historic documents and don’t show up on the only eighteenth-century map of Santa Fe.

Research showed that most of the weight-bearing, east–west foundations were consistent with engineering specifications for two-story buildings in Spanish presidios. Parallel to and north of the Palace, the southernmost foundation we found beneath the north wall of the Palace Print Shop once undergirded the north wall of the eighteenth-century courtyard. Segments of north–south cross foundations indicate that the dimensions of the spartan rooms were 16 to 22 feet east to west by 16 feet north to south. I combined our findings with those from previous studies of buried cobble foundations around the western Palace perimeter in Lincoln Avenue and a few foundation stubs found while the museum was under construction. This approach enabled me to define two east–west rows of rooms stretching 235 feet from the middle of Lincoln Avenue east to the west end of the Segesser Hide Room, and a third row of rooms that extended 70 feet to the west wall of the New Mexico History Museum. All told, the buildings contained twenty-one rooms within an eighteenth-century presidial complex that covered nearly 10,000 square feet.

Certainly Nusbaum had heard the stories about the post-1791 presidio, and he was sure there was an extensive seventeenth-century compound of government buildings, but the earlier, eighteenth-century presidio was unknown to him. Our 2002 excavations resurrected, for everyone, the forgotten pre-1791 presidio that the US military demolished in 1867.

More Surprises to Come

As we undertook the current stucco demolition and replacement, we kept the Palace’s long record of surprises in mind. Nusbaum preserved good examples of eighteenth-century adobe walls and details within the Palace, but the north wall of the building was more closely linked to the nineteenth century, when the Palace was often in a state of disrepair or dilapidation. In the early part of the century, a Mexican governor mourned that pigs and chickens roamed freely, and the doors lacked locks. Curiously, when the Americans arrived in 1846, General Stephen Watts Kearny found the Palace habitable, and his men lived in the serviceable presidio outbuildings. Yet, throughout the 1850s and middle 1860s, territorial governors continued to lament the condition of the walls and roof. In response to complaints, the United States Congress appropriated $5,000 for a major update of the Palace in 1867 and 1868. Workers replaced the north wall of the east half of the Palace and demolished 60 feet of rooms on the west end and 30 feet on the east end, shortening the Palace to its current 260-foot length. Servant’s quarters, warehouse rooms, wood houses, a carriage house, and a stable bounded the courtyard on the north. The wood houses were open to the south. In 1890 additional wall repair in the east end of the Palace signaled that the earlier repairs were less comprehensive than reported.

Nusbaum found the Palace and the buildings north of the courtyard in poor condition only nineteen years later. Nusbaum was the first to apply cement-based stucco on the outside of the Palace. About forty years later, it was replaced and recoated, leaving a very thick layer over the older adobes. The dangers of using cement stucco over adobe bricks are well known to modern preservation architects. The most common problem occurs when water seeps behind the stucco and slowly dissolves the adobe bricks, leaving a hard cement coating and a rotted, structurally unsound core. Fortunately for all involved, the walls were in reasonably good shape and only required spot patching or reinforcing—a miracle, considering they had not had a comprehensive assessment of their integrity for more than 100 years.

For my part, I examined the north wall of the Palace and the south and west and east walls of the courtyard buildings as the old stucco was removed and the walls were assessed for repairs. I found only twenty-one fragments of historic pottery and butchered sheep, goat, and cattle bones embedded in the bricks and mortar. One hardware cleat embedded in the north Palace wall had been used to suspend a sign or a lamp from the wall.

Judging from the size of the adobe bricks and the pattern in which they had been laid up in the wall, the north wall of the Palace appeared to date after the 1840s. The western lengths of the wall had more charcoal and organic material, but little or no straw, which would have indicated adobe-making methods used before 1860. Most of the eastern portion of the Palace north wall and the courtyard building walls had adobes that were mixed with straw and had fewer embedded artifacts, suggesting the adobes were made during 1867 and 1868. In the north wall, the 1890 repair exhibited adobe bricks similar to those used in earlier construction, but the mortar was a lime cement. To my knowledge, this was the first use of lime mortar in the Palace. Later use of lime mortar occurred with Nusbaum’s renovation, where we see its extensive use between the upper courses of adobe bricks that he inserted to raise the height of the buildings. Also, his lime-mortared adobes contrast markedly with those in the mud mortared walls built in 1867 and 1868. It was easy to differentiate wall sections from these two important construction or remodeling episodes. In the south walls of the courtyard buildings, I could see the special care that Nusbaum took to leave as much of the original fabric in place as possible.

Archaeological and architectural examination, combined with timely archival research by the New Mexico History Museum staff, has revealed a sequence that is not well known to the public. The configuration of the courtyard buildings changed with museum administrators’ visions of the best way to use the space. Seventy years of rebuilding, remodeling, and repairing the north courtyard building walls left an invisible patchwork of materials, styles, and colors beneath the stucco.

The Palace is not a frozen monument to the oft-cited four cultures that have melded into what we know as Santa Fe and New Mexico. Archaeological studies, coupled with small- and large-scale renovations, have reminded us that the Palace and its spaces are as organic and alive as the people and cultures for whom it was a seat of government. The evolving history of the Palace teaches us to leave our narrow and normative frameworks at the door and open up to the promise that it has more secrets, mysteries, and wonders to reveal. If we can only take time to look, it offers endless keys to unlock the hidden doors of history. I can only daydream about what new wonders and surprises the interior walls and unstudied subfloors of the Palace have in store for us.

Stephen Post is an archaeologist and research associate and former deputy director for the Office of Archaeological Studies, Department of Cultural Affairs. He is the co-curator, with Josef Diaz, of Santa Fe Found: Fragments of Time, located in the west end of the Palace, which opened in 2009 and is scheduled through May 21, 2030. He first experienced the intrigues of Palace archaeology in 1978.