Radio Killed the Sheet Music Star

The golden age of DIY music enjoyment is back for an encore at the New Mexico History Museum

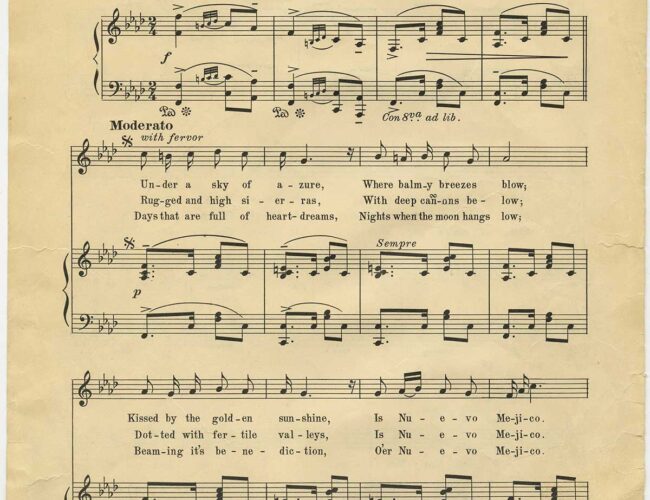

“O, Fair New Mexico,” Gamble Hinged Music Company, 1915. 13 × 10 in. Courtesy of the James M. Keller Collection.

“O, Fair New Mexico,” Gamble Hinged Music Company, 1915. 13 × 10 in. Courtesy of the James M. Keller Collection.

BY MEREDITH DAVIDSON AND JAMES M. KELLER

Before radio and television, when making music at home was the evening’s entertainment and playing the piano was considered an essential talent among the middle class, sheet music was the music consumer’s gateway to the world. The New Mexico History Museum celebrates this era with sheet music of popular songs about the State of New Mexico, dating from the 1840s to 1960, in the new exhibition The Land that Enchants Me So: Picturing Popular Songs of New Mexico (opens March 2, 2018). The show spotlights graphically striking sheet music covers from the era, along with other printed materials, sound recordings, and memorabilia relating to New Mexico and its musical life. Co-curators Meredith Davidson and James Keller sat down to share more about the exhibit’s process and materials with our readers.

MD: What makes this exhibition significant?

JK: Popular music doesn’t automatically spring to mind when one thinks about historical documents, but these songs really can tell us how people who sang and played them viewed their world. In that sense, popular song was a form of media during its golden years. At the turn of the twentieth century, everybody sang and many people played the piano; more pianos were sold in the U.S. in 1899 than any other year in our history. A piano was an essential part of a well-appointed home. With the introduction of sound recording, sheet music gradually became less important, and music lovers increasingly became listeners rather than performers. They didn’t have to make their own music, and they became more passive in their relationships to songs. Still, recordings and sheet music coexisted happily through the 1920s until the advent of radio, which signaled the end of the golden age for the sheet music industry. Of course, music continued to be published after that, but it became less compelling as a visual object.

MD: Your interest in music is certainly a life passion, but the popular sheet music you’ve acquired over the years seems less directly tied to your professional background, which is in classical music. How did you come to start collecting, and what have you been able to do with the materials so far?

JK: The story really begins on an airport runway in Missouri. In the late 1980s, I was living in New York City and doing some musical direction for a New Jersey-based theater company that specialized in shows relating to historical Americana. On the plane after a Missouri performance, the company’s director said to me, “I wonder if there were any songs written about New Jersey. It would be great to do an historical revue of songs about the state.” We guessed there might be a couple, but never enough to do a whole show. But the idea lodged in my mind; about 150 songs later, I had uncovered way more than enough to mount a show called The Garden State Songbook, which also took the form of an art exhibit in New Jersey.

Once bitten by the regional song bug, I got interested in songs about American places everywhere. Since then, the collection has grown to be quite large. In 2012, I mounted a substantial exhibition on the history of California as seen through popular songs. It ran for more than a year in San Francisco, and then toured to regional museums throughout that state. I’ve lived in New Mexico for several decades, so naturally when I came here I started collecting pieces about the Southwest. Now New Mexico gets its turn to shine. The New Mexico History Museum’s exhibit focuses on printed sheet music covers, but also includes period audio recordings, and even some film clips highlighting our state.

MD: What does the term popular music mean to you and how are we defining it within the exhibit?

JK: I think of popular music as distinct from either classical or folk music. These are songs or instrumental pieces, composed by identified composers who use a musical and poetic vocabulary that is easily accessible to all listeners.

MD: What would be a good example of a song that really did catch on?

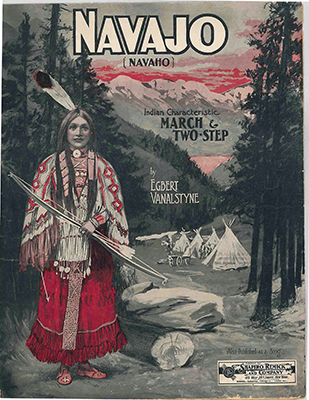

JK: The earliest successful New Mexico–related song is “Navajo,” published in 1903. It was the breakthrough hit for composer Egbert Van Alstyne and lyricist Harry Williams—two vaudevillians. The lyrics begin, “Down on the sand hills of New Mexico.” This was one of the best-selling songs, nationally, of 1904. It was recorded by multiple artists, and released in several editions, and it launched Van Alstyne on a path of composing many songs on Southwestern themes.

MD: Those covers are some of the most visually stunning in the show; Tin Pan Alley publishers seem to have understood the value of catching people’s attention.

JK: The term Tin Pan Alley came into being around the turn of the twentieth century. It referred specifically to the music publishers clustered in a single neighborhood in New York City. A songwriter remarked that the chaotic noise of all the pianos playing at once made the street sound like a tin pan alley. The name became so well-known that people began using it to refer to the popular music industry in general. The field reached its high point in the period of the 1890s to the 1920s, and during that time, music publishers, just like book publishers, knew the power of a beautiful cover for luring in potential buyers. In the nineteenth century, they used creative typography, and then around the turn of the century, they commissioned artists to paint scenes depicting whatever the song was about: cowboys, beautiful landscapes, comical images. Quite a few covers in our exhibition are the work of artists who became specialists in sheet music illustration: very accomplished artists and designers whose full-color covers contributed to the sales success of these pieces.

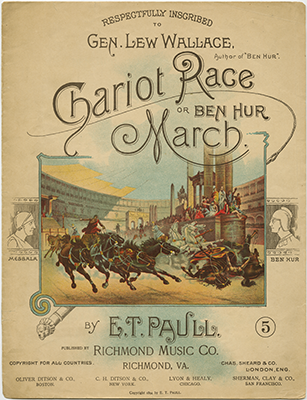

MD: Another set of songs follows the popularity of the nineteenth-century novel Ben-Hur. The book was written by New Mexico’s governor at the time, Lew Wallace, presumably in the Palace of the Governors.

JK: It became the best-selling novel of the nineteenth century, surpassing Uncle Tom’s Cabin, and it remained the best-selling novel in the United States until it was, in turn, toppled by Gone with the Wind. We include several pieces of sheet music directly inspired by the narrative and characters of that novel. One of them was a big success: Chariot Race or Ben Hur March by composer E.T. Paull, who published his march with a detailed color cover that set a new standard for sheet music aesthetics. Even today, many people will recognize this as an old-fashioned circus march, but it was originally created to depict the famous chariot race in which Ben-Hur vanquished his Roman rival.

MD: While many of the works were issued by major publishers in New York or Chicago, what I find most charming in the show are those that were published locally, or those highlighting a specific detail of a place. Many of the songs were written by people who may have never set foot in the state, so they often reflect generic Southwestern ideas, but the local pieces are so charming because they highlight areas we know and love.

JK: We include a number of pieces that relate to New Mexico communities and cities. Often these were self-published by their authors. Through the middle of the twentieth century, you could send your song to a company that would set it in musical type for a fee, and print maybe a hundred copies, making anybody a potential music publisher. There is something heartwarming about realizing that a local music teacher or church organist composed a piece to celebrate his or her own town, be it Ruidoso or Carlsbad or Aztec. These songs convey a palpable sense of local pride.

MD: When you first approached the museum, you said there was a particularly rare gem in your collection. Could you share more about our prized piece in the show?

JK: Our official state song is “O, Fair New Mexico,” by Elizabeth Garrett, who was the daughter of Pat Garrett, the Lincoln County sheriff famous for shooting Billy the Kid. Elizabeth grew up as a typical ranch girl in southern New Mexico, although she was blind practically from birth. Her parents decided that she would not be raised differently from her siblings, and as a result, she grew up to be an absolutely remarkable woman. She excelled in music, and became an accomplished pianist. She traveled to Chicago to study voice; she spent time in New York, where she cultivated a close friendship with Helen Keller; and became one of the first people to employ a seeing-eye dog. She moved back to New Mexico, and was a valued member of the state’s musical community until her death in 1947.

We are grateful to be able to share with the public a hitherto unknown phonograph recording of Elizabeth Garrett singing “O, Fair New Mexico.” So far as we know, it is the only copy in existence. She made it in 1924 in Chicago at the studio of Marsh Laboratories, a pioneer in the newly devised electrical method of recording. Marsh made some of the earliest recordings of musicians who became important jazz figures, like King Oliver and Jelly Roll Morton, but it also served as a sort of vanity label. You could walk in and make your own recording and leave with a copy of it. That’s what we think happened here.

I was unbelievably lucky to acquire this record. Several years ago, I ran across an online auction catalog from a dealer in Germany who specialized in rare 78-rpm records. It listed “O, Fair New Mexico” on the Autograph label, which I recognized as a division of Marsh. But the auction had taken place almost a year before. Nevertheless, I sent an email to the dealer asking if he remembered any details about this record. He wrote back to say that, in fact, someone had bought the record in that auction, but he never received payment and therefore still had the record in his possession. He offered to sell it to me if I wanted it—which I did! Not until it arrived did I see the label, which lists the performer as Elizabeth Garrett. This was a find of immeasurable importance for the musical history of New Mexico.

MD: We had the pleasure of getting to play it with a friend of the museum, Andy Baron, who is a specialist in early recording technology. In an intimate listening session, he played the record on different early phonographs with different kinds of needles. What stood out in your mind about the recording itself?

JK: I found it thrilling. To actually hear the voice of this woman singing ninety years ago was a deeply moving experience. She never achieved a national career as a singer, but she was very accomplished. She had a well-trained voice produced in the manner of an opera singer. In New Mexico, she was constantly in demand as a recitalist, and it is easy to understand why.

MD: I was surprised by the quantity of songs that were available to choose from—more than a hundred.

JK: I’m surprised by it too! Those of us who live here are well aware that we are a corner of the country that is often overlooked—which may not be a bad thing—but the fact is that during the decades when people loved to sing, they sang about New Mexico just as they sang about everything else. This exhibition reminds us of a time when people felt that the place where they lived was something to sing about.

Meredith Davidson is the curator of 19th- and 20th-Century Southwest Collections at the New Mexico History Museum. Musicologist James M. Keller is the long-time program annotator of the New York Philharmonic and the San Francisco Symphony and is a journalist on the staff of Pasatiempo /The Santa Fe New Mexican.