Fundamentals for a Diné Gathering

BY LUCI TAPAHONSO

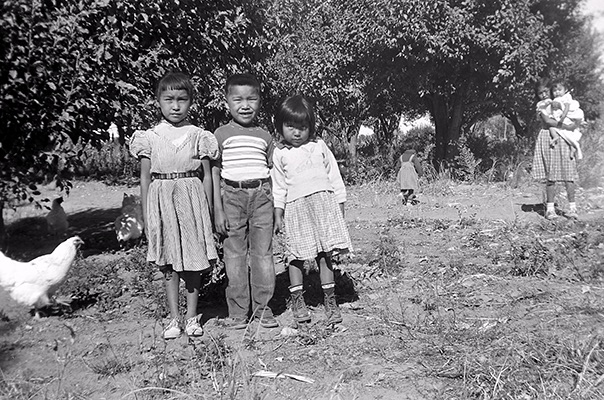

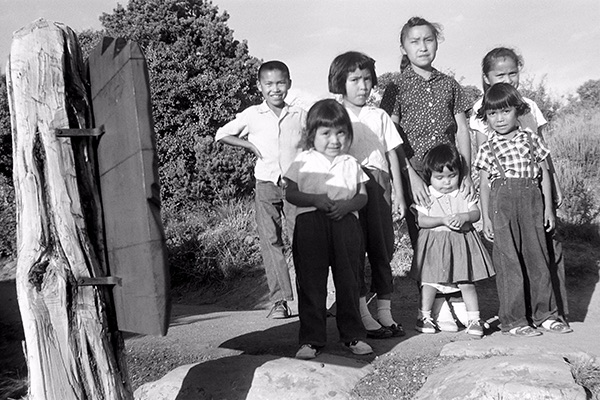

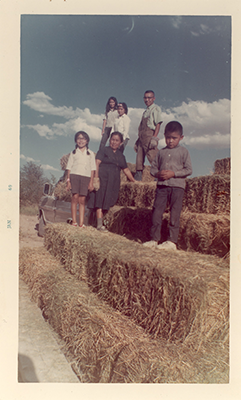

The enticing scents and dishes of a Diné family meal are always accompanied by children running around and playing nearby, dogs who have that hungry look, and quiet teenagers who lounge about and sometimes help cook and serve. And the large get-togethers are replete with stories, laughter, and sometimes, nostalgic tears. Our family gatherings usually take place at my late parents’ home in Shiprock, which faces Dzil Náóooldilii (Huerfano Mountain), one of the six sacred mountains

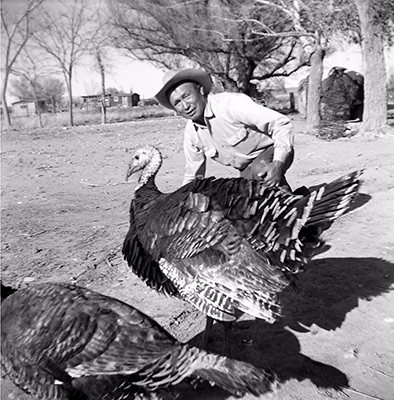

Interestingly, the main dishes at these gatherings are connected to the sacred mountains which outline Dinétah (Navajo homeland), and the places where our primordial deity, Changing Woman, was born and raised. It is said that when the world was created by the Holy People, they placed sacred mountains in each direction to designate boundaries. In the north, they placed Dibé Nitsa, Big Horn Sheep, and thus, sheep and goats became a part of our tradition and lifestyle. Traditional stories also teach that the holy people, First Man and First Woman, were made from perfect ears of white and yellow corn, and thus nadáá, corn, also holds deep spiritual and cultural significance.

When our families gather in the house where we were raised, we share memories of preparing food together. Although our parents have now passed on, the same atmosphere exists. We enjoy nitsidigo’i (kneel down bread) or other corn dishes, tortillas, fry bread, coffee, lemonade, and tasty courses of mutton or lamb. New generations of children play and run about and the dogs still hope for a bit of food amid stories and laughter.

CORN

I remember the early summer mornings when our parents went to the corn field to collect pollen from the tips of the stalks. They prayed as they carefully shook the fine yellow powder into a white enamel bowl. The bowl of pollen was set out of reach on a high shelf. It is an essential element in prayers and ceremonies and is considered food of the Holy People.

In summer, we children slept in a chaha’oh, a shade house constructed of leafy tree limbs and logs. The night breezes and drifting sounds of sheep or goat bells and snorting horses lulled us to sleep. At dawn, we bounded out of bed and ran barefooted down the slight hill to the fields and orchard. There were just-ripened tomatoes, long crispy green beans, cantaloupes, watermelons with the telltale creamy oval resting on the damp soil, crisp apples, fuzzy peaches, apples, and bunches of purple and green grapes. We’d come back to the chaha’oh with armfuls of our spring efforts: planting, irrigating, hoeing and finally, harvest.

I also recall the making of nitsidigo’i. My mother asked the boys and men to dig a large, round hole about four feet deep which would serve as an oven for the nitsidigo’i. They built a fire alongside the oven.

Traditionally, the corn was ground while kneeling before a metate, or grinding stone, thus the name kneel down bread. Instead of a metate, we had a corn grinder attached to a pole between two trees. The entire process was a family endeavor. One child shucked the corn, another cut off the kernels (saving the corn liquid, or milk) and set aside the husks and corncobs—the husks to wrap the ground corn and the corncobs for the animals. The grinding of the corn required three or four helpers: one to feed the grinder, another to turn the handle, and still another to hold a bowl beneath for the ground meal. After filling several bowls, we stirred in the corn milk. One person held the husks open, and another poured the thick batter into the bowls of the husks. Then we folded the husks on both ends and tied them closed with thin strips of husk.

Meanwhile, those taking care of the fire spread hot coals into the pit, which were removed when the nitsidgo’i were ready to be placed on the hot bottom of the pit. We covered the nitsidgo’i with foil or a large piece of cardboard, shoveled dirt in, followed by a layer of hot coals, then topped it all with fresh kindling. The bread baked for an hour or so, and was nicely browned when unearthed.

The scent, taste, and texture of fresh nitsidigo’i is unsurpassed: sweet, chewy, and slightly crispy. Other delectable corn dishes include steamed or dried corn, ‘alkaan (sweet corn cake), k’íneesbízhii (corn dumplings) and leeh shibéézh (pit-steamed whole corn).

Nitsidigo’i is considered a delicacy and is especially cherished when made in this traditional way because of the family effort, from the initial planting to the underground baking. Another rare dish made similarly is the Kinaaldá cake, which is made only during a girl’s puberty ceremony. In this instance, the grinding and mixing of the corn batter is the primary duty of the Kinaaldá, as part of her introduction to womanhood.

The ceremonial Kinaaldá cake, nitsidigo’i, and nadaa lees’áán (cornbread patties) were the Navajo people’s only breads before flour was introduced in the late 1800s, when our ancestors were captives at Fort Sumner. Thereafter flour, salt, baking powder, and lard became staples that we transformed into thick, tasty tortillas and fluffy fry bread. Coffee was also introduced to the Diné table during this time; the combination of corn breads and cakes and black coffee remains a favorite.

MUTTON AND LAMB

Similar to corn, sheep figure prominently in Navajo philosophy and lifeways. Spider Woman, a holy person, taught women to weave so that they could contribute equally to a household and to the community. Her husband, Spider Man, constructed a loom, a symbolic replication of the Diné world view. These tapestries made from wool have evolved into refined works of art which contain intricate creation stories, prayers, ritual songs, and ancient ceremonies. Sheep and goat wool also provide blankets, clothes, toys, and bedding. Early on, bones were made into knives, needles, serving ware, hoes, and other utensils.

It is said that “sheep are our parents.” They nurture us, clothe us, keep us warm, and provide companionship. They also symbolize mental and spiritual well-being, and embody healing qualities. When feeling ill or lonely or depressed, we are encouraged to eat a bowl of mutton stew. It’s one of those entrées that elicits the remembrance of specific events, family members, the scent of a particular place or season, and the voices of loved ones. Stews and freshly made breads are the essence of what it means “to eat for” someone in celebration of a graduation, new job, homecoming, birthday, or other success.

Mutton and lamb dishes are imaginative and varied. Roasted mutton/lamb sandwiches on a tortilla or fry bread are a favorite at roadside food stands, and garnishes vary by region. When we order sandwiches with green chile, it signals that we’re from “around Shiprock.” Navajos in Arizona favor lettuce, onions, and tomatoes instead.

Food that is cooked on an open fire lends a distinct flavor to everything; the scents mingle with the shouts of children, dogs barking, and laughter. As we move to tables, other classic dishes appear, including the ubiquitous pink or green stuff that consists of marshmallows, cottage cheese and canned fruit; potato and green salads, yeast bread, lemonade or Kool-Aid, fast-food chicken, baked pastries, and ice cream. Other typical dishes include pueblo oven bread, pinto beans, and Jell-O with whipped cream.

There are always a few minutes of stillness when the blessing is offered. Even the dogs pause and lie down. Little ones run to be held by their parents or siblings. The prayer evokes the Holy Ones, the sacred mountains, nearby irrigation ditches and river, the compassion and teachings of our parents and other elders, the fields that continue to sustain us, the animals, and finally, our families, which are both nearby and widespread.

Prayer, gratitude, and memory are the required appetizers and desserts which complete the quintessential family dinner of corn, bread, coffee, and mutton.

In writing this, I remembered that in my father’s final weeks, he consumed only blue corn mush and water, which had provided sustenance for all of his 101 years.

Luci Tapahonso is the inaugural Poet Laureate (2013–2015) of the Navajo Nation, and Professor Emerita of English Literature and Languages (University of New Mexico).