Unnatural Resources

Indigenous artists from the two different hemispheres talk trash—and discuss the vital alchemies of their art-making

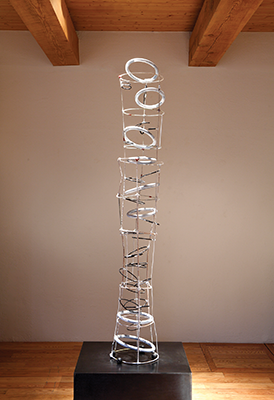

Aymar Ccopacatty, Ch’ullu for a New Leader, 2010. Plastic bread bags, grocery bags, plastic netting, caution tape, and fabric litter. 10 × 3 1⁄2 ft. Promised gift of Patricia M. Newman, Museum of International Folk Art (IL.30.2017.1). Photograph by Blair Clark.

Aymar Ccopacatty, Ch’ullu for a New Leader, 2010. Plastic bread bags, grocery bags, plastic netting, caution tape, and fabric litter. 10 × 3 1⁄2 ft. Promised gift of Patricia M. Newman, Museum of International Folk Art (IL.30.2017.1). Photograph by Blair Clark.

BY AMY GROLEAU AND MARLA REDCORN-MILLER

As artists, Aymar Ccopacatty (Aymara) and Nora Naranjo Morse (Santa Clara Pueblo) each explore the question of non-biodegradable waste in Native communities through their art. Independently and on separate continents, Ccopacatty and Naranjo Morse both noted the overshadowing presence of landfills on their respective ancestral lands, and saw the trash as a kind of natural resource—similar to the way that artists have harvested natural fibers from sheep to make weavings, or pulled clay from the earth to make pottery.

Ccopacatty, who grew up in a textile-producing community in Peru where wool and camelid fiber were the predominant natural resources from which to weave and knit, now uses plastic bags and trash found in and around Lake Titicaca for weaving. Naranjo Morse, who was raised in a family of potters in northern New Mexico, produces kinetic mixed-media sculptures from the refuse found in the landfill outside of Santa Clara Pueblo. Both artists apply traditional core values of resourcefulness, ingenuity, and respect for the environment in a decidedly unromanticized, modern context. As the following telephone conversation unfolds, old dichotomies, such as traditional versus contemporary or natural versus synthetic, are absorbed into their projects—then dissolve as they work through and reconfigure what it means to practice art as an indigenous artist in today’s world.

Nora Naranjo Morse: I’m curious about where you live, what the landscape looks like, and how you got interested in making art this way.

Aymar Ccopacatty: My family is from Lake Titicaca in Peru. It’s on the border with Bolivia, and that is kind of where the influence and techniques come from for weaving, knitting, crochet, braiding: many creative fiber art techniques from the Aymara tradition and colonial European influences. My mother is from the U.S., so I’ve always been back and forth between places. But the traditions of textiles, and the native language, Aymara, have definitely really impacted me. At 12,000 feet, the landscape in Peru is very mountainous and dry. There are a lot of uses of natural resources; my people make braided rope and reed boats out of tall grasses. There are a lot of old traditions and handwork still in daily life. The people have a self-sufficient farming lifestyle.

I realized when I was twelve years old that if I didn’t learn a lot of these weaving techniques, they might be lost, both within my family—my grandmother just passed away about eight years ago—and in the larger community. I remember when my family got electricity in the nineties. The Socca community doesn’t yet have to pay taxes because they are a Native community, but the government is trying to erase those lines and make them like any other municipality of Peru that receives funds from the government. The Peruvian government is big on records; they want to push birth certificates and death certificates. My community faces the challenge of maintaining traditions in the face of overwhelming government interventions on all levels, aimed at homogenization of a very diverse, multilingual area.

Nora: My community, Santa Clara Pueblo, used to be agrarian, but now we are dependent on food sources from outside of the community. Santa Clara has also been inundated with social and cultural transformation. We are struggling with these shifts in our communities, and struggling with the consequences every single day. One of those shifts prompted me to start looking at what we’re embracing as contemporary Native people. We are consumers now, going to Walmart with our meager incomes and buying a lot of plastic-based products, and then basically throwing that stuff away at our community dump. One day when I went to gather clay—something that I had been doing almost all my life—I saw so much discarded material in close proximity to a traditional clay pit, and I was greatly affected.

At that moment, I realized I’d been living in denial about what I consumed and how and where I discarded waste. Without reasoning why, I walked into the dump and started collecting everything from plastic to fencing wire. I took it to my studio and started cleaning it up. I began deconstructing the materials I had collected, but in a way, I was also deconstructing my own attitudes as a consumer. I began to question so many issues. What did it meant to be a contemporary Native person consuming in this sort of careless manner, especially since I was raised with an entirely different value system and consciousness?

Stepping into this new creative portal has transformed me and the way I make art. I now am reconstructing my attitudes and creative intention concerning my work, culture, and community. Since this realization I’m even more determined to challenge expectations by a non-Native audience of what Pueblo clay art should look like. This makes earning a living far more challenging, but in the end, protecting my creative and cultural integrity is most important to me.

Aymar: It is absolutely tormenting. I have bags of plastic that I brought from my community [near Puno, Peru] all the way to where I am now in Rhode Island. And it is sitting there, and it is some kind of an experiment, because supposedly some of it is actually supposed to biodegrade with time, and break up. And some of it does and some of it doesn’t. Some of us can just go on living in a dream state of ignoring reality, and some of us just can’t take it and have to sit there and do this dance with it. I spent a year asking that stuff: Who are you? Where do you come from? Why are you here?

I make these pompon kind of things from plastic, which creates a thousand little pieces that are so small that I have these crazy thoughts of boiling it all up and trying to pour it into a mold. But then I’d be poisoning myself. I am not supposed to be burning and melting plastic, but I have these fantasies of finding a place for those small pieces, because it’s just painful to throw it in the trash when that’s the whole point: Get it out of the trash!

Nora: Well, that is what is so great about art. Art forces you to think out of the box, and traditionally, that’s what Pueblo people did all of the time. For my ancestors, thinking that way was a form of surviving. Trash is my biggest resource at this point, besides the clay and other organic materials I use in my work. Some of the pieces I made of trash are very tall, wire pieces; they are wonderfully kinetic. What I discovered with these pieces was that when the wind blew through the studio and caused movement, they would dance, but eventually topple over. I ended up making clay stabilizers for the bottom of the forms, so that they could still be kinetic, but they would be stabilized. What this meant to me is that whatever we do to this earth, it is still the stabilizing force of our existence.

Aymar: Wow, that’s a wonderful metaphor, because it’s the opposite of what we would like on so many levels. We would like to be without trash; I’m noticing the potent symbolism of counterbalancing the found materials (trash) with the clay, the Mother Earth. To participate in the modern world, you buy something—even if you are buying a necessary thing, like diapers—that will end up in a landfill. I have small children and diapers drive me crazy.

People are always really amazed by the stuff you can make in plastic, like textiles, but then they go back to seeing plastic as mundane, something they can throw out on the street. And it is just collecting. It just piles up. It can be really depressing, it can be really too much. Whatever you can do, keep that spark of energy, that original intent of an honest conversation with the refuse—so the refuse can be welcome. As weird as that sounds, that has to continue.

Nora: Yes, that is really true. I think the thing that keeps me going with this new creative expression is that I’m always going back to the main reference point: the Earth. As a contemporary Pueblo woman, I am articulating my relationship with the Earth. It’s a relationship that’s been influenced by the people that I come from. And how I articulate that in my work and share it with people, whether they understand it or not, is an important element in my process as a human being. It is my passion. I make art every day. It’s become a nutrient to my soul. And now I know, Aymar, that there is someone else, somewhere else, doing and thinking the same thing because that really does help, and I hope that someday we can cross paths so that we can continue this conversation.

You can see Ccopacatty’s sculpture Ch’ullu for a New Leader at the Museum of International Folk Art’s exhibition Crafting Memory: The Art of Community in Peru through March 2019. New works from Nora Naranjo Morse’s series Remembering will be coming to the streets of Albuquerque as the artist takes out bus ads to encourage others to remember and protect “the sacredness of life, no matter who we are, where we’re from, or where we’re going.” For more information on this project, visit noranaranjomorse.squarespace.com.

Amy Groleau is the curator of Latin American collections at the Museum of International Folk Art. Marla Redcorn-Miller is the deputy director of the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture.