Photo Synthesis

Documents and photographs important to Native history have long been treated like personal souvenirs by non-Native people, but as this story shows, reparations are achievable.

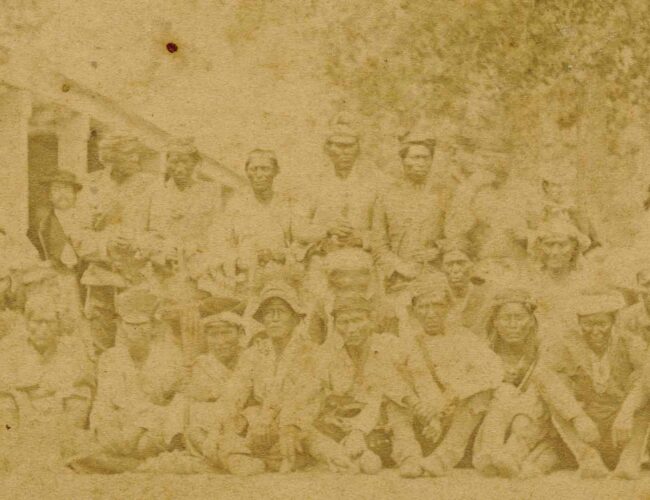

Outdoor group portrait of Diné (Navajo) men, probably photographed around the time of the Navajo Treaty negotiations at Fort Sumner, New Mexico in 1868. Depicted in the photograph are Chief Barboncito, Manuelito, and Manuelito’s brother Cayetanito (all seated in the lower right corner). Narbona Primero is also in the front row. Jesus Arviso is standing at left in the back row (with a hat and mustache). The man standing second from the right may be Benjamin Stone Roberts. Photograph by Valentine Wolfenstein. General William Nicholson Grier photograph collection. National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution (P20819).

Outdoor group portrait of Diné (Navajo) men, probably photographed around the time of the Navajo Treaty negotiations at Fort Sumner, New Mexico in 1868. Depicted in the photograph are Chief Barboncito, Manuelito, and Manuelito’s brother Cayetanito (all seated in the lower right corner). Narbona Primero is also in the front row. Jesus Arviso is standing at left in the back row (with a hat and mustache). The man standing second from the right may be Benjamin Stone Roberts. Photograph by Valentine Wolfenstein. General William Nicholson Grier photograph collection. National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution (P20819).

BY HANNAH ABELBECK

One hundred and fifty years ago, thousands of Navajo people undertook a second arduous 300-mile journey across New Mexico as the first Native nation to—with the 1868 Bosque Redondo Treaty—negotiate a return to their homeland.

This year, two significant historical records turned up just in time for the commemorations. The first is a copy of the 1868 Treaty, recently unearthed from the attic of a descendant of negotiator Colonel Samuel Tappan. The second is a rare photograph I found, taken during the week of treaty negotiations and long thought to have been lost. Despite the highly significant moment they mark—the creation of the Navajo Nation and formalization of government-to-government relations with the United States—neither the photograph nor the Tappan copy of the treaty have been available to the Diné people for 150 years.

As a photo archivist, I’m no stranger to the time-consuming, deep challenges of working with dispersed photographic material. But in this case, the ordinary difficulty of this process was compounded by the long legacy of troubling relationships between collectors, historical institutions, and Native communities. Documents and photographs important to Native history have long been treated like personal souvenirs by non-Native people. Both the treaty copy and photographs were kept by American military personnel and passed down to their descendants. While the objects survived and were cared for, their remarkable stories also suggest just how much Native history has been lost, sold, forgotten, mislaid, hidden, remains privately owned, or is languishing in cultural institutions far from the communities they document. One hundred and fifty years of distance, inaccessibility, and misinterpretation have added insult to injury.

I began researching photographs from this era in 2015, while helping Devorah Romanek, curator at the University of New Mexico’s Maxwell Museum, and Khristaan Villela, now director of the Museum of International Folk Art, with loose ends while they were researching the Souvenir of New Mexico album at the Palace of the Governors Photo Archives. The Souvenir, also called the Meem album, is a bound set of 63 photographs marking three major events underway in 1866: the Long Walk, the French Intervention in Mexico, and post-Civil War military expansion (and profiteering) in the Southwest. These interrelated subjects are seldom discussed together, yet the Union personnel who photographed, compiled, owned, and circulated the album’s images were personally invested in all three projects.

Until the Souvenir album was donated to the Photo Archives in 2007, the Museum of New Mexico only had copies of the individual pages photographed on nitrate film, probably in the 1930s when John Gaw Meem purchased the album. Consequently, while the images have long circulated as illustrations, the bound album had infrequently been interpreted as a set of photographs. Especially significant is the rare subset of portraits of Diné people taken during their internment at Hweeldi (Bosque Redondo). A few of the images are widely published, like the portrait of a Navajo man with a bag, powderhorn, and bow on the cover of Dee Brown’s Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee. Six other copies were owned by an Army officer named Charles Jennings, who took them back to New York. His son copyrighted them in 1914.

Untangling potential circumstances surrounding the creation and the circulation of these images—and other related photographic material from the 1860s Southwest—was part of the research process for Romanek’s forthcoming book about the album and its photographs. Intrigued and baffled by what we could find and what we couldn’t, I spent many evenings searching for additional photographs to help disambiguate, contextualize, and attribute work by photographers who passed through New Mexico territory during the era. The photographers capable of taking portraits of Navajo people make for a very short list. The photographic process was difficult, supplies were rare, and photographing Navajo people in military custody was a type of access that not every photographer had.

The most promising potential portraitists are a colorful and motley crew. They included N. Brown e Hijo (Nicholas Brown and his son William Henry Brown), who in the 1860s split their time between St. Louis, Santa Fe, and Chihuahua. Also promising were Constant and Victor Duhem, enlisted brothers and French immigrants who arrived in New Mexico from Gold Rush California in 1862 with the Union Army. Other potential contributors included Gaige, whose first name is in dispute, but who was paid to photograph forts and died in Arizona in 1869; William A. Smith, who wanted to work with Gaige and liked to eat at La Fonda; and William Abraham Bell, a British physician who learned photography during a two-week crash course when he joined the Kansas Pacific Survey in 1867 and who may have abandoned his glass plate negatives in the Southwest (not to be confused with British photographer William H. Bell of the 1872 Wheeler Survey). Their photographs have been difficult to distinguish from one another’s work, especially since much of it has been missing, scattered, jumbled, unattributed, misattributed, and apocryphal.

Valentine Wolfenstein, a young Swedish immigrant who took a photography lesson in St. Louis before traveling west over the Santa Fe Trail, was one of the few to capture photographs at Fort Sumner. Early in the search, I found a folder in the Palace of the Governors Photo Archives with correspondence between former photo curator Richard Rudisill and historian Frank McNitt, discussing Wolfenstein’s work. Around 1970, they’d learned from a descendant of Wolfenstein’s that the photographer had been at Fort Sumner in 1868. He had a small room set up as a photographic studio when General William T. Sherman arrived to conduct the treaty negotiations with Navajo leaders. In fact, Wolfenstein wrote in his journal that Sherman even helped him set up one of the shots, arranging the group and the camera, which helped him “take the best pictures I have so far.” McNitt joked that “the odds of finding these old prints probably is one million to one, but I am starting on the trail.” Neither McNitt nor Rudisill ever found a copy. Devorah and I laughed that it would probably be our wild goose chase too.

In his journal, Wolfenstein wrote that he mailed a set of eight photographs to General Sherman. For me, like for McNitt and Rudisill 45 years ago, the Sherman angle hasn’t produced anything (yet), despite multiple attempts. But Sherman’s papers weren’t the only option.

The Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian has a Wolfenstein photograph of Head Chief Barboncito that once belonged to a descendant of William N. Grier. According to Wolfenstein, he departed Fort Union at the same time wagon trains of Navajo people left for Dinétah. But Wolfenstein traveled to Fort Union, where he went to play the flute at a wedding celebration. He took $75 worth of prints with him, photographs he took at Fort Sumner. Because I had noticed that the provenance of related photographs from 1860s New Mexico could be traced to people who were in the territory during those years, I discovered that Grier probably arrived in New Mexico to command Fort Union around the same time as the wedding. Curious what other photographs Grier may have had access to, I asked the NMAI archivist if other photographs arrived at the Smithsonian along with it.

I was hoping for any additional images from this era—by the Browns, by the Duhems, by anyone. The archivist sent a pdf with thumbnail images. The blurry, faded image would not have seemed remarkable to almost anyone else, but I recognized the group photo Wolfenstein described taking, even though it was vaguely captioned, unattributed, and misdated.

I immediately contacted Jennifer Denetdale, a Diné historian and a descendant of Manuelito and Juanita, to let her know what I suspected I had found.

In the photograph, Barboncito, Manuelito, and his brother Cayetanito appear in the front row, seated at the far right, with a small boy who may be Barboncito’s son. The three men, all important political leaders, are dressed exactly the same as they are in related studio portraits Wolfenstein made, which means that those may have been taken during the week of treaty negotiations as well. The whole group is large, and may contain many, maybe even all, of the headmen that negotiated and later signed the treaty. A few of the older signers died within a few years of their return, and this might be the first and only time they posed for photographs. A few other people are recognizable, including Narbona Primero in the front row and interpreter Jesus Arviso in the back, both of whom were photographed again in 1874 when a delegation of Navajo leaders traveled to Washington, DC to discuss pressing concerns with President Grant. At the center of the group is an unidentified Diné woman, who may have played an important role in the events.

When I found a second copy of the group photo this spring with the caption “Navajos treating with General Sherman to return to their old homes,” it was an incredible confirmation that our confidence in the photograph’s identification was warranted. This other, smaller nineteenth-century copy was once owned by anthropologist Clyde Kluckhohn, and it has been at Harvard’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology for over fifty years.

The Navajo Nation Museum’s month-long exhibition on the Naaltsoos Saní (the 1868 Treaty) opened June 1. Along with the first copy of the treaty, on loan from the National Archives, the exhibition includes a wall-sized reproduction of the identified photo. The photograph offers a glimpse into a moment when Native people successfully argued against the odds for their tribe’s survival and return to their homeland, but it can also be seen as more than that. Not as a souvenir or curio, but as a long-submerged image of Navajo leaders, reunited with a Navajo institution that is using it to tell its own story.

Hannah Abelbeck is the digital imaging archivist at the Photo Archives of the New Mexico History Museum/Palace of the Governors. The archives can be searched online (with the option of ordering prints) at palaceofthegovernors.org/photoarchives.html.