From Ineffable to Incandescent

The trauma and transcendence of Agnes Pelton

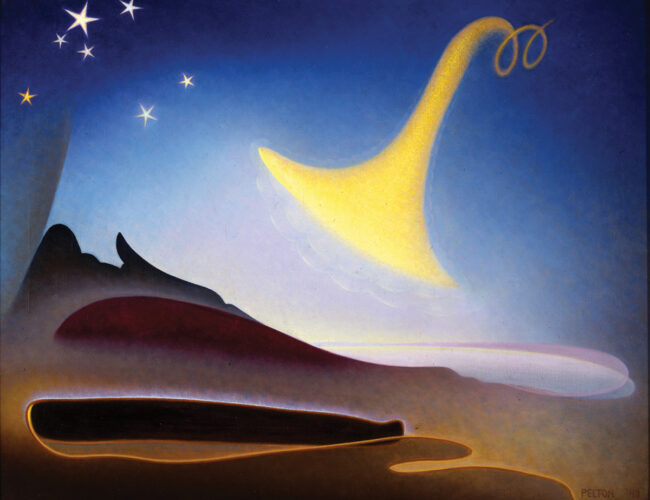

Agnes Pelton, Awakening (Memory of Father), 1943. Oil on canvas. Collection of the New Mexico Museum of Art. Museum purchase, 2005 (2005.27.1). Photograph by Blair Clark.

Agnes Pelton, Awakening (Memory of Father), 1943. Oil on canvas. Collection of the New Mexico Museum of Art. Museum purchase, 2005 (2005.27.1). Photograph by Blair Clark.

BY NICOLE PANTER DAILEY

Trauma forms people. It frames their actions and reactions. It determines what a person believes and how they move through the world. That the artist Agnes Pelton grew from a frail, sickly, quiet child into a frail, sickly, deeply introspective young woman prone to depression becomes less of a surprise when her personal and family history is explored—and the complexity of her seminal paintings can be appreciated all the more with a clear knowledge of this history. Pelton’s work is on exhibit at the New Mexico Museum of Art in Agnes Pelton: Desert Transcendentalist, organized by the Phoenix Art Museum, through January 5, 2020.

In 1875, six years before Agnes Lawrence Pelton was born, trauma was spliced into her family’s DNA. Her maternal grandfather, Theodore Tilton, a prominent leader in the abolitionist movement, became the white-hot center of a national scandal. He sued Henry Ward Beecher, the charismatic minister and high-profile fellow abolitionist (and by many accounts, accomplished philanderer) for committing adultery with his wife, Pelton’s grandmother. The scandal and the subsequent trial, which ended in a hung jury, dominated the front pages of American newspapers for nearly three years. The ordeal profoundly affected everyone in the Tilton family. In the wake of the scandal, the Tiltons’ marriage was shattered; Pelton’s grandfather fled to France and her grandmother stayed in the United States.

Pelton’s parents were both American ex-patriots who lived in Germany, where she was born. In the first four years of her life, she and her mother moved from Germany to Brooklyn to Basel, Switzerland. Her father lived with them part of that time, but mostly he seems not to have been present. When Pelton was four, she and her mother moved back to Brooklyn, where her mother opened a music school.

Shortly after that, Pelton’s father left the United States again. After spending some time in Europe, he eventually died of a morphine overdose in Louisiana in 1891. Pelton was nine years old, and the loss remained acute throughout her life.

One of her most moving paintings, Awakening (Memory of Father), painted in 1943 when the artist was 62 years old, deals with the loss of her father. In her extensive diaries, Pelton has written that her family never spoke of the scandal and that the atmosphere of her childhood home was extremely religious and emotionally repressed. It is not surprising that the child who longed for a father, emotional expression, and warmth—yet deprived of all three—developed a host of chronic physical ailments and depression, which followed her into adulthood.

There are different kinds of trauma that have their own unique resonances. There is, for instance, the inherited trauma of a disastrous family narrative, the consequences of which may reverberate through generations.

Another form is the lived personal trauma of the individual, which happens when there is a firsthand near-death experience—or the death or loss of someone close. Children who lose a parent when they’re young are often unable to process the loss, and will experience and internalize that loss with far more confusion than an adult would. When these events occur in succession without the original trauma being addressed and processed, as happened to Pelton, the trauma compounds. It becomes complex and much more difficult to untangle.

In addition to the personal and family trauma, Pelton lived in a chaotic world that must have felt as if it was teetering on the edge of complete annihilation. In 1905, when Pelton was 24, the Russian Revolution began. The mass political unrest culminated in 1918 with the assassination of Czar Nicholas Romanov and his family. The bloody and hard-fought revolution radically changed the course of that nation and the world. Russian intellectuals, such as Pelton’s spiritual teacher Nicholas Roerich, saw it as a sign of a coming apocalypse.

In 1914 World War I engulfed Europe, Pelton’s childhood home, and was quickly followed by the Spanish flu pandemic that killed as many as 100 million people worldwide. As if to put an ex-clamation point on the chaos that was enveloping the whole world, Pelton’s mother, with whom she still lived and was very close, died in 1920. It was against this background that, in 1921, Pelton fled to a deserted windmill on Long Island to make her first explorations into the abstract depictions of her inner spiritual landscape.

Transcendence is, by definition, to experience existence beyond the known physical world. When we seek transcendence, we do so because our reality is, in some way, unbearable; perhaps the world in which her luminous biomorphic forms lived was the balm for her, even more so than was the act of painting.

In 1925, Pelton painted The Ray Serene, the first of a series of radiant ciphers. In a world where personal and global equilibrium were in short supply and tragic events were plentiful, the act of making art was soothing—the burning, broken world receded into the distance while she painted, her spirit soared as the translation from the ineffable to the comprehensible took place.

From her writings, we know that Pelton recognized she had grown up in a joyless environment. It is probably no coincidence that shortly after the death of her emotionally repressed (and repressing) mother, Pelton felt freed to paint those wildly emotional abstracts, an intuitive remedy to the complex trauma that had been ever-present in her life. There are a multiplicity of self-soothing behaviors that can arise to protect the individual from the havoc trauma can inflict upon their psyches. Art-making (along with art-viewing) is a valuable tool that can help us process and integrate trauma.

When regarding Pelton’s body of abstract paintings, the viewer is immediately struck by the naked emotionality of the work. As a child Pelton was taught that the expression of emotions was off limits, but her emotional nature demanded an outlet. Like Rothko and Pollock, passionate universes radiate from marvelous, mysterious, non-objective forms in Pelton’s work. Her bioluminescent images dance and shimmer. Still, upon closer examination, a nearly imperceptible darkness hovers around the edges of most of these canvases. Pelton’s learned experience taught her that darkness always lurks nearby.

Like many people who experience early personal turbulence, Pelton was drawn toward the spiritual from a young age. Her self-guided path toward enlightenment included investigations of theosophy, Buddhism, Hinduism, astrology, and meditation—then considered fringe pre-occupations in America, but now ubiquitous pursuits for spiritual seekers. Many of the philosophies Pelton was drawn to hold a core belief that destruction makes room for rebirth, and in that rebirth lies transcendence. It’s a hopeful narrative arc, given Pelton’s personal trajectory.

One major spiritual influence was Nicholas Roerich, a Russian artist, philosopher, scholar, and mystic. Roerich founded the discipline of Agni Yoga, which became a lifelong meditative practice for Pelton. The viewer can see a direct line between his mystical, electric landscape paintings and Pelton’s own otherworldly creations. Yet her acuity outstrips the master’s talent—her canvases are far more accomplished than Roerich’s.

Like art, processing trauma through the exploration of religion and the spiritual is one of our most potent intuitive strategies to manage deep wounds and difficult emotions. Pelton’s spiritual explorations led her to the meditative states during which the abstract images she depicted would appear to her. These works, viewed either individually or as a body of work, are powerful, luminous maps of her thoroughly plumbed inner landscape.

After relocating to Long Island in 1921, Pelton traveled to then-exotic places—Hawaii, Syria, and New Mexico. She eventually left Long Island and moved to the California desert, where she began painting representational desert landscapes in addition to the abstracts she continued to paint until the end of her life. Her desert paintings, which are much less inspired, sold to tourists in the Palm Springs area where she finally settled. They enabled Pelton to keep food on the table and a roof over her head long after her family money ran out.

Much of the history of painting is a continuum of human attempts to connect with, illustrate, and then communicate the experience of the painter’s inner spiritual vision to the viewer. Some of these attempts fail. Others are … well, transcendent.

Pelton’s abstractions, her depictions of her very personal spiritual universe, fall firmly into the latter category. In a body of work like hers, in which every abstract is impossibly brilliant, Departure (1952) is a tour de force. It is a flawless combination of composition, shape, and color that makes the viewer long to leave the mundane temporal world behind. It’s abstract, yet it’s also a very literal visual translation of the idea of transcendence. It is a painting that makes the heart beat faster; it takes the viewer in and gives us a glimpse of what it must feel like to dwell forever in the perfect beauty and balance of Pelton’s spiritual realm.

Pelton was ahead of her time. She began her work in isolation, doggedly pursuing her line of creative exploration despite public indifference to her work. When she began her quest for transcendence in the early part of the twentieth century, the line of scholarly investigation she followed was considered part of a crackpot fringe. The disciplines she explored did not become part of the Western cultural mainstream until the late 1960s, thanks to the counterculture revolution.

Pelton died in 1961 in genteel poverty in an earthly landscape she loved and which gave her some hard-won inner peace—the village of Cathedral City near Palm Springs, in the shadow of Mt. San Jacinto.

Unfortunately, Pelton didn’t live to see the widespread acceptance of her spiritual beliefs, nor to see the national recognition of her abstracts as the dazzling, numinous masterpieces they are.

Dr. Nicole Panter Dailey is a psychologist who splits her time between Los Angeles, Palm Springs, and Santa Fe. Panter Dailey also teaches screenwriting at California Institute of the Arts. She grew up in Palm Springs in the shadow of Mt. San Jacinto.