We Like Your Digs, Your Style, and Your Art

A portrait of the American Southwest via legendary gallerist Elaine Horwitch

By Julie Sasse

Elaine Horwitch was a major force in contemporary art in the Southwest from the late 1960s until her death in 1991. She was responsible for launching the careers of hundreds of artists from the Southwest and the nation. She promoted the integration of fine art and crafts as well as contemporary Indigenous, Latino, and Southwest art within global art contexts. Horwitch opened her first art business in Scottsdale in 1964 and the first Elaine Horwitch Galleries in Scottsdale in 1973, followed by galleries in Santa Fe in 1976, Sedona in 1982, and Palm Springs in 1986. She was a catalyst for the rise of what has been coined “Southwest Pop” and the “Art of the New Southwest.”

With a spotlight on Horwitch’s colorful life, galleries, and artists, Julie Sasse’s Southwest Rising: Contemporary Art and the Legacy of Elaine Horwitch (Tucson Museum of Art and Cattle Track Press, 2020) surveys art in Arizona and New Mexico from the middle of the nineteenth century through the early 1990s, revealing the artistic journeys and accomplishments of hundreds of artists, galleries, and art professionals who contributed to the Southwest’s rich cultural heritage.

In the book, excerpted here, Sasse, who worked at Elaine Horwitch Galleries for fourteen years, presents a combination of biography, memoir, and a historical overview of the arts and the rise of contemporary art in Arizona and New Mexico.

Photograph courtesy Julie Sasse.

Horwitch Opens in Santa Fe

As early as 1956, Elaine and Arnold Horwitch began to visit Santa Fe on a regular basis and made a special trip in 1958 to attend the second season of the Santa Fe Opera at its open-air theater with panoramic views of the countryside. O’Keeffe and other noted celebrities were known to frequent the opera, so it was a thrill to spot many of the cultural elite who were an essential part of the artistic fabric of the region. […] In the summer of 1974, after years of making regular trips to Santa Fe, the Horwitches rented a condominium at Fort Marcy Compound on 320 Artist Road to look into the idea of opening a gallery. Horwitch often spoke to her artists about expanding into Santa Fe, including [Billy] Schenck, who hoped she would act on her dream so he could have a new venue for his work. Coming out in the summer, she investigated the art market, became involved in the social activities of the town, and learned about the various artists who were establishing themselves in the area.

Opening a gallery in Santa Fe was Horwitch’s dream come true. Her daughters were growing up; Wendy was almost twelve, Mindi and Deena were in high school, Carrie was living on a kibbutz in Israel, and her son Mark was away at Harvard. She was finally able to travel more freely and invest in the time it would take to launch a gallery in Santa Fe. As Horwitch later recalls:

I wanted to find a place to spend four or five months a year where the weather wasn’t so hot. But I thought that I should have a reason to be here, a gallery. People told me that you could not sell contemporary art in Santa Fe. My husband thought I was crazy, but he went along with it. I knew that we could make it here. You have to have a certain amount of intuition about what you are doing.

In 1976, the Horwitches moved to a new house at The Compound and found a location for a gallery on 129 West Palace Avenue, only a block and a half from the Plaza. The gallery was a short walk to the Museum of Fine Arts and the Portal of the Palace of the Governors, where Native American and Hispanic artisans had come to sell their wares since the early twentieth century. Her building had deep roots in presenting regional crafts for which Horwitch later became known. The ample space, still adorned on the ceiling with the original white-painted embossed tin tiles, was owned by Leonora Curtin Paloheimo, who established and operated the Native Market in the mid-1930s to promote New Mexico folk arts and crafts.

Although a legacy existed at this historic site, it was not a guarantee of a successful enterprise. Melding Southwest contemporary art and folk art with nationally and internationally acclaimed artists was a risky business, considering the deep trench that had drawn boundaries between art and craft over the centuries. However, artistic lines were being blurred since the late 1960s, and the plucky Horwitch accepted and even encouraged the melding of the two disciplines. The Paloheimos were the Horwitches’ landlords, and Yrjö Palaoheimo often stopped by the gallery to visit and conduct business with Arnold. While from different eras and artistic aims, Paloheimo and Horwitch were both enterprising women who shared a deep love of the Southwest and a dedication to supporting arts and crafts from the Southwest. […]

With such an illustrious history of 129 West Palace Avenue, Horwitch had big shoes to fill, but she was up to the task. On June 27, 1976, she opened her season with a great flourish, a group show of works by [Fritz] Scholder, [Earl] Biss, and Sam Francis, an unlikely trio, but it brought in a crowd. However, Horwitch was never one to keep things simple, and her strategy of diversity was well-received. According to John Hamilton of the Santa Fe Reporter:

The building has been beautifully renovated into a light, airy and attractive space for the display of a pot-pourri [sic] of paintings, drawings, sculptures, ceramics, wall hangings and jewelry which offers something for everyone who likes contemporary or modern art. Welcome to Santa Fe, Elaine Horwitch. We like your digs and your style and your art. There wasn’t a dog in the exhibition.

Biss was an obvious choice for Horwitch’s Santa Fe season. Scholder had ignited a contemporary Indian art movement in Santa Fe, and Biss was already showing promise at her Scottsdale location. Furthermore, his studio in Santa Fe was in a new complex on 2200 West Alameda, just down the street from Horwitch’s gallery. Several other artists had also moved their studios away from historic Canyon Road to the cheaper complex, including [T.C.] Cannon, [Douglas] Hyde, [Peter] Jones, and Kevin Red Star. At the space, artists could work without interruptions from the throngs of tourists combing the streets of Canyon Road yet still conduct business with serious buyers.

Of the Alameda group, Horwitch had shown Biss, Hyde, Jones, and Red Star in her Scottsdale gallery. She really wanted Cannon, but he had an exclusive with Aberbach Gallery in New York City. Although the action was at Horwitch, these artists were aware that they could not compete with their mentor and Horwitch’s star artist—Scholder. Everyone knew that Scholder came first. He insisted on vetting her artists and expected her to show him extreme generosity. Horwitch bought Scholder a dark green 1937 Jaguar. When he gave it to his wife Romona, Horwitch did not react. She simply gave him a Rolls-Royce. Within a year, only Scholder remained at the gallery.

Everyone in town came to Elaine Horwitch Galleries’ grand opening. One newcomer to Santa Fe not only attended the festivities, he also got a job. David Rettig knew of and admired Scholder and was a friend of Cannon, meeting him in 1975 when he was a work-study student at Dartmouth and they were artists-in-residence. Cannon encouraged him to move to Santa Fe, so he took him up on the challenge. Rettig came to the grand opening of Elaine Horwitch Galleries and a week later, he paid another visit with Cannon:

There was road construction out front, so it was muddy and hard to get to. I came into the gallery with T.C. Cannon to apply for a job. Elaine recognized T.C. and called out, ‘I want to buy one of your paintings!’ He declined because he only showed with Gene Aberbach in New York at the time, a man who owned Sun Records and made his fortune off Elvis Presley. She kept badgering him to sell her a painting to no avail, so she said, ‘What about a car—do you want a new car? Let’s trade!’ So, T.C. answered, ‘I want a truck, and my friend here needs a job.’ T.C. never got the truck, but I got the job.

The Action in Santa Fe

In the 1980s, Santa Fe’s population had reached almost 50,000 residents, nearly tripling in size since 1940, and new exclusive housing developments were spreading out beyond the city limits. Nonprofit agencies became more prominent as a result of the infusion of financial support. For example, the Western States Arts Federation (WESTAF) established its headquarters in Santa Fe, serving a twelve-state region of support to the arts. Additionally, Stuart Ashman became the Visual Arts Coordinator at the Foyer Gallery at the Armory for the Arts, later becoming the coordinator for exhibitions at the Governor’s Gallery. In the heart of the city, the Museum of Fine Arts revived Alcove shows, bringing back the tradition of supporting artists from the region that had spanned 1917 through the 1950s. Promoting film, video, performance art, and other new media, Rising Sun Media Arts Center, founded in the late 1970s by Bob Gaylor and Linda Klosky, transformed into the new Center for Contemporary Arts in 1983. At first, the center occupied a gallery in the basement of the Armory for the Arts until locals raised money for a new building on the Armory campus in the mid-1980s.

The art market was a key catalyst for the support of the arts in the region at that time. Santa Fe was reported in the press as being third in art sales volume next to New York City and Los Angeles. Sophisticated new gallery guides proliferated, and publications devoted to the arts increased, including the launch of Artlines magazine in northern New Mexico in 1980, founded in Taos by Nancy Pantaleoni and Stephen Parks. Fashion designers, writers, actors, movie directors, musicians, conductors, and visual artists flocked to the city, and Elaine Horwitch Galleries was the meeting place for everyone to get the latest art gossip, find a good restaurant or nightclub, and get on a party list—all while sales were in constant motion. For example, the Duke and Duchess of Bedford, who lived on a five-acre estate called Rancho Viejo, bought art from Horwitch and often came in to see the new arrivals of art and artists.

Elaine Horwitch Galleries was a first stop for well-heeled new residents. In the early 1980s, Nancy and William Zeckendorf, Jr. arrived in Santa Fe from New York City, where William had been a real estate developer. Nancy and William met Horwitch through mutual friends Marjorie and Julian H. Levi, a Chicago lawyer and urban renewal advocate. Levi had worked with William “Bill” Zeckendorf, Sr. in Chicago in the 1950s. When Frank Lloyd Wright’s Robie House was slated for demolition in 1958, Levi enticed Zeckendorf, Sr. to purchase the historic house to preserve it. The Zeckendorf family had a long history in the Southwest, beginning with Aaron Zeckendorf, who founded a mercantile company in Santa Fe in 1854. Nancy fell in love with Santa Fe before she married William when she was a principle dancer with the Metropolitan Opera and danced for the Santa Fe Opera Company. In 1983, the Zeckendorfs purchased the site of the historic Big Jo Lumber Company at 309 San Francisco Street and began to make plans for their latest real estate venture, the Eldorado Hotel. Opening in 1986 to great fanfare, the 200-room, fifteen-million-dollar Santa Fe Style hotel was touted as the latest and largest luxury hotel in Santa Fe. Hundreds of the most prominent Santa Fe residents came to the grand opening as a benefit for the Santa Fe Community Foundation.

One of the special features of the hotel was the formidable presence of contemporary Southwest art, including large- scale works by [John] Fincher, Douglas Johnson, and other Horwitch artists. As Nancy Zeckendorf recalls:

Elaine’s gallery was always the place to go to see new art and she introduced everyone to everyone. Bill was so grateful for his friendship with her when we first came to Santa Fe, and we were like family. We bought paintings by Fritz Scholder and Judy Rhymes from the gallery and Bill rode horses with her. When we decided to build the Eldorado, he gave the Horwitches a small interest in the hotel, and in exchange, Elaine supplied the art.

Nancy could always count on Horwitch to participate in her many philanthropic projects, including the Santa Fe Opera and the Lensic Performing Arts Center, developed by her husband. Horwitch knew everyone in town, and she had the clout to make introductions and wrest substantial amounts of money from her many clients for worthy causes.

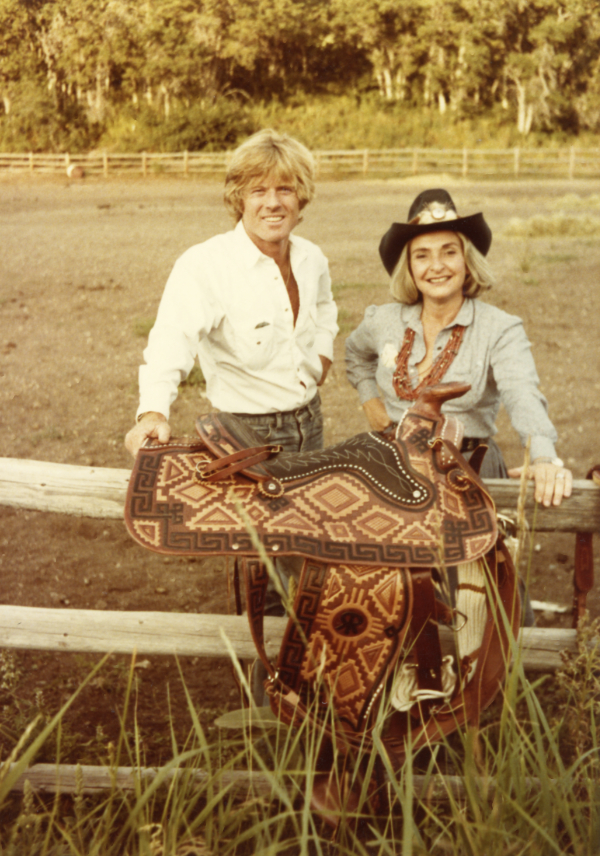

Photograph courtesy Nancy Silver.

Fashion designer Ralph Lauren, who launched his “Santa Fe Collection” in the fall of 1981, came regularly to Horwitch’s gallery with his wife Ricky to buy Indian jewelry and blankets for his Native American and frontier-inspired fashions. Designers Zandra Rhodes and Jean-Charles de Castelbajac also paid visits to the gallery, staying to talk about their ideas and getting new ones from Horwitch’s eclectic offerings. Horwitch kept an open copy of People magazine at the front desk to spot a passing celebrity, and she never hesitated to grab someone off the street to bring them into the gallery if she knew them to be famous. Often, Horwitch’s staff would alert her to notable patrons if she did not recognize them. The day that Rhodes first came to the gallery, she was not aware that the flamboyant magenta redhead was a famous clothing designer and snarled, “Who is she? She’s not a buyer.” Employee Steven Ward replied, “You don’t know who that is Elaine? That’s Zandra Rhodes. She’s one of the greatest fashion designers in London.” Within minutes, Horwitch was busy making Rhodes her new best friend. She occasionally did not know some of the important people visiting her gallery, but it was of no consequence because they were eager to make her acquaintance. Horwitch was a celebrity in her domain.

Santa Fe not only became a top destination city, it also became the subject of a “road show” at Lord & Taylor’s department store in April of 1982. Called “Focus America,” the Santa Fe Chamber of Commerce, Horwitch, and other gallerists assembled artists and artisans for the special display, including a reconstruction of Horwitch’s bedroom in her Santa Fe house. Weavers, potters, jewelers, folk carvers, and fine artists were included in this special event. Felipe Archuleta, Brian Blount, [Randy Lee] White, Char & Sher fashion designers, Galisteo potter Priscilla Hoback, and several Native American artisans displayed their works, which stoked the fires of desire for all things Santa Fe in New York City and beyond.

Keeping pace with the influx of celebrities, artists, and movies to the area, new restaurants began to spring up, making Santa Fe a food as well as an art destination. Mark Miller was one of the most notable. In the 1970s, Miller had worked for Williams-Sonoma and at Alice Waters’s Chez Panisse restaurant, noted for its innovative cuisine. In 1979, he started his first restaurant, the Fourth Street Grill in Berkeley, followed by the Santa Fe Bar and Grill in the same city. Miller first visited the Southwest in the mid-1970s on a road trip and had long been entranced by the region. With the success of his two new restaurants in California, he bought land outside of Santa Fe in the Jemez Mountains. In 1985, Miller moved to Santa Fe permanently and opened a restaurant called the Coyote Café, influenced by Leroy Archuleta’s carved cottonwood coyotes. Miller’s restaurant was a favorite of artists, collectors, and tourists, and he decorated his café with works by many of Horwitch’s artists.

Horwitch in Santa Fe: Paradise Found

Horwitch’s life revolved around riding her horses in the hills near her home, attending Indigenous dances, going to the flea market, and interacting with artists, collectors, and celebrities, who embraced all that Santa Fe had to offer. When she rode, Horwitch’s cowboy/caretaker Phil Kniffen saddled and unsaddled the horses and put them to pasture. Kniffen lived in a rustic one-room adobe house on the property with his wife Gloria, when they were not at their own home in Nambé. Within a couple of years, Dale Harris, a handsome jeweler and horse wrangler who always wore clanging spurs in the house, replaced “cowboy Phil.” Harris moved his family into a pre-fabricated house, stuccoed to look like adobe, that Horwitch installed on the property, and turned the old adobe hut into his jewelry shop. Both Kniffen and Harris enjoyed the “city slickers” who came to visit Horwitch and the attention they received as her cowboys.

Immersing herself in Santa Fe culture, in the 1980s, Horwitch rode her horse, festooned with an ornate silver saddle and bridle, in the Fiesta Parade. Horwitch increasingly took on the appearance of a cowgirl. She was often seen in her office leaning back in her chair, picking her teeth with a toothpick, and crossing her legs on her desk, her revolver in plain view. She wore colorful knee-high Larry Mahan cowboy boots from her stash of thirty, a straw cowboy hat with feather adornments from Fast Eddie’s hat shop in Aspen, a denim prairie skirt, and a fitted plaid shirt with pearl snaps. Every outfit was embellished with a classic silver concho belt and layers of fetish, turquoise, and silver necklaces. Her look was so distinctive that some noticed that Riva Yares stopped dressing in Western clothes, perhaps realizing that she had met her match.

As at her gallery in Scottsdale, Horwitch needed to increase her staff for her growing operation in Santa Fe, and in 1980, she added the quiet and inquisitive Steve Piepmeier to her Santa Fe sales staff. Working with Ann Wilson, he became a trusted employee for six years, carefully observing the dynamics of collectors, employees, and artists. Over the years, in vivid detail, he recorded in his journals the parties, arguments, sales, and emotional outbursts in the gallery. In 1984, Horwitch hired the statuesque Kelly Cozart, a recent bachelor of fine arts graduate in ceramics at Texas Tech University in Lubbock. Cozart’s husband Brett had recently taken a position at Shidoni, and Cozart worked at the gallery part-time while raising a newborn son. A fresh-faced young woman from Idalou, Texas, she was thrust into the sophisticated art world, and Horwitch and Pfaelzer never hesitated to make fun of her heavy Texas drawl and naïveté. Cozart took it in stride, believing that her experience at the gallery was “like getting a graduate degree in the business of art.” With her beauty and positive outlook, she soon became one of the most popular gallerists at the Santa Fe gallery.

Soon after Horwitch hired Cozart, Horwitch added John Guernsey to her Santa Fe staff, a handsome, introspective man, newly arrived from Colorado to work on a new Zen center in the area. Answering an ad in the newspaper, Horwitch quickly hired him. Guernsey had never worked in a gallery before, so he learned to install and handle art on the job. Guernsey found Horwitch’s quirks amusing, recalling, “She always had a phone in each ear, a cigarette in her hand, and a hamburger on the desk in front of her.” To him, part of the appeal of the gallery was that everyone worked hard but enjoyed it, and every day seemed like a party, with all gravitating around Horwitch. The staff started to make cappuccinos in the back kitchen and serve them to the artists who came to the gallery to hang out with Pfaelzer, and tequila or martinis for themselves after a long day of catering to demanding artists and finicky collectors.

Business was so good that Horwitch added Nicholas Sealey to her Santa Fe team to work with Guernsey in 1985. Sealey was an art-circle insider in town who had been working as a crater and shipper for Ancient City Art Shippers before starting his own crating business, so he knew the volume of art that went in and out of the gallery. Tall, dark, and handsome with a seductive British accent, he charmed the artists and customers alike, calling everyone “love.” Horwitch knew that he would be an asset as a preparator, but he could also sell art to her wealthy clients who enjoyed interacting with such an attractive and engaging young man. Women of all ages streamed into the gallery throughout the day asking for Sealey to show them art, often avoiding the trained female staff in front of them.

Photograph courtesy Julie Sasse.

Truckloads of art needed to go back and forth between Scottsdale and Santa Fe, and staff would do the same, working wherever they were required, depending on the season. In Scottsdale, Horwitch had a pool table at her home, and staff would play with her before breakfast and at the end of the day. Ward, [Lisa] Fisher, [Rudy] Fernandez, [Christopher] Pelley, and I often came to Santa Fe to work during the summer months and stayed at the Horwitch house, where work and fun intermingled. Life at the Horwitch compound was always exciting. For instance, while digging post holes on the property, Ward found vintage slot machine parts buried in the dirt, which fueled the rumor that Horwitch’s historic house, built by New Mexico governor John J. Dempsey in the 1930s, was a gambling house and brothel at one time. During off-hours, Ward enjoyed the good life. He rode horses with Horwitch and her friend Ali MacGraw, practiced roping with her caretaker, and prepared art for private showings with celebrities, including Michael Keaton, Rob Halford of Judas Priest, and Sylvester Stallone. Swaggering and flirtatious, both Ward and Sealey became Horwitch’s two favorite employees, and she treated them more like friends than staff. But while Horwitch enjoyed their charismatic qualities, she was no pushover. She knew how to channel their confidence and good looks into sales and an enjoyable work experience for everyone.

During seasonal work, some staff slept in a converted garage bedroom on the bottom floor next to Horwitch’s housekeeper Mia. Others stayed in what Horwitch rather insensitively referred to as the “Anne Frank room,” a spacious bedroom hidden behind a false door off the kitchen. Later, she purchased the house next door for staff to use in the summer. Those who stayed at her compound were allowed unfettered access to the two large refrigerators in her commercial-grade kitchen. If she brought in extra help for Indian Market and the house was full of guests, she would rent rooms for the staff at the De Vargas Hotel, a cheap hotel with few amenities at the time. Staff found a way to make it fun, using toilet paper for napkins at impromptu cocktail parties, and inviting Horwitch and her visitors to join them in their downtown antics.

Horwitch treated staff like family, but she did not tolerate it when some got too close to her artists or engaged in bad behavior, and she could turn on a dime from best friends to tyrant if staff became too personal with her clients. “She could be the fun art dealer making it fun for everyone or the Wicked Witch,” recalls one employee. “If she got pissed, she was like Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. She had a way of giving a pass to all the men and always held the women accountable.” Other staff saw her mood swings differently—some noticed that when Horwitch’s energy level dipped, she began to pick a fight to get her adrenaline up. Even with her strict standards and volatile temper, some staff often willingly worked on their days off and vacations, or rented their own apartments in Santa Fe, simply to be where the action was.

During Indian Market, Horwitch was always on the lookout for free help. She also had summer interns, many whom were the sons and daughters of New York City and Paris gallerists or other art professionals. Interns were given basic duties and limited access to Horwitch’s inner circle of artists and collectors. Still, their pedigrees and youth added intrigue and a new level of cultural cachet to the gallery name. For example, Sharron Lannan, the daughter of J. Patrick Lannan, Jr., whose father established the Lannan Foundation, worked in the Santa Fe gallery for a summer, much to the delight of the male artists, who found her attractive.

David Aberbach was another intern at the Santa Fe gallery. His father, Joachim Aberbach, was an art dealer and the founder of Hill and Range Songs, noted for publishing such hits as “I Walk the Line,” “Frosty the Snowman,” and “Love Me Tender.” Aberbach opened his Manhattan gallery in 1973 and represented T.C. Cannon, so he was well aware of Horwitch’s presence in the Southwest. In 1986, he sent his son to spend the summer with Horwitch so he could learn the art business without his direct influence. However, the young Aberbach was not a dedicated gallerist and preferred to spend more time smoking pot in the storage building than to learn the business. As employee Carol Sherman recalls, “One day, Guernsey handed him a can of paint and a paintbrush and told him to do touchups in the gallery. He splattered paint over several paintings, so Guernsey hauled off and slugged him.”

–

Julie Sasse is the author of more than forty published art books, exhibition catalogs, and essays. Dr. Sasse is the chief curator at the Tucson Museum of Art, where she has organized more than 100 solo and group exhibitions of regional, national, and international artists.

El Palacio presents this excerpt in advance of an associated exhibition, Southwest Rising: Contemporary Art and the Legacy of Elaine Horwitch, slated to open at the New Mexico Museum of Art on March 13 and to run through January 2, 2022. Due to uncertainty caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, please call the museum to confirm details before scheduling your visit.

The book Southwest Rising: Contemporary Art and the Legacy of Elaine Horwitch is available for purchase from the Tucson Museum of Art and Cattle Track Press.

Southwest Rising was written with contributions from research conducted during a residency by the author at the Women’s International Study Center, Santa Fe, New Mexico.