Trading Places

Seeing the Santa Fe Trail from the flip side

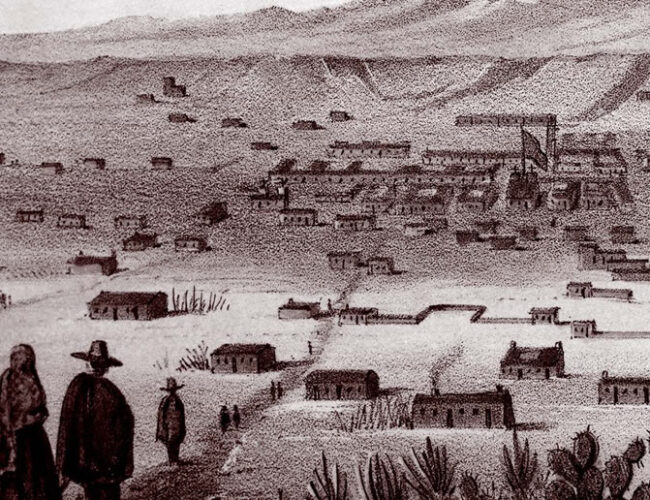

View of Santa Fe. Lithograph. Copy negative reproduction from original color lithograph, in Report of J.W. Abert of His Examination of New Mexico in the years 1846–47 to the Secretary of War, 1848 (p. 132, Plate I), ca. 1846–1847. Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA)

View of Santa Fe. Lithograph. Copy negative reproduction from original color lithograph, in Report of J.W. Abert of His Examination of New Mexico in the years 1846–47 to the Secretary of War, 1848 (p. 132, Plate I), ca. 1846–1847. Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA)

BY FRANCES LEVINE

Before I moved to Saint Louis, I must admit that I only thought about the impact, challenges, and changes that the Santa Fe Trail brought to New Mexico.

My perspective broadened as I came to understand the Santa Fe trade from the Missouri perspective. After I became a Saint Louis resident, I expanded my study of history to this French colony in Upper Louisiana, as this part of Missouri was known in the eighteenth century. Many traces and connections can be found surprisingly close at hand—in my own neighborhood, in the Missouri Historical Society Archives, and at historic sites I have visited.

Santa Fe and Saint Louis are linked by centuries of history. They began as colonies of competing empires, but were united gradually through commerce on the Santa Fe Trail. Over one thousand miles separate them. That distance spans the heart of the North American continent. The trail links vastly different regions. It begins in Missouri, near the lush confluence of the Mississippi and Missouri river drainages. That landscape gives way to the Great Plains in Kansas and Oklahoma, then gradually to the high desert and Rocky Mountains at the western end of the trail in northern New Mexico. Geographic and cultural diversity found along the trail undergirds its history.

During Spain’s rule of New Mexico (1598–1821), Spain outlawed trade between the two regions. When Mexico declared its independence from Spain in 1821, it lifted those trade restrictions, allowing Missourians and other Americans to enter New Mexico. After embarking on my own journey of research and reorientation, the following significant journeys stand out most to me.

Frontiers Meet

Diaries and letters, official reports, and casual observations of travelers tell us so much about the connections that grew from the “commerce of the prairies”—the title of trader Josiah Gregg’s 1844 book about the trail and the trade. Of course, there are few records of what Native people thought of the newcomers, and most of the written materials come from the pens of the eastern observers. The journey transformed many of the participants in Santa Fe Trail expeditions, and in some cases their reputations and place in history were made by their crossings of the expanding American nation.

When Missouri traders first ventured west on the trail in 1821, Santa Fe was a village of about five thousand people. The first reaction of most Santa Fe Trail travelers, after spending many weeks on the road, was utter disappointment. Santa Fe was not the charming, alluring place that it is today. Its dusty plaza was the center of the community, marked by the often dilapidated Palace of the Governors on the north side of the plaza and the parroquia, or basilica church grounds, on the east. Franklin, Missouri, was even smaller in 1821, with a population of only about one thousand. But it was second in size only to Saint Louis, and it was already a crossroads of commerce where trade caravans gathered for the western journey. The burgeoning American nation met the waning Spanish and Mexican nations on the Santa Fe Trail, first in commercial partnerships and then as the lead actors in the American conquest of Mexican territory.

First Contacts

Among the fascinating contenders for the title of first to visit Santa Fe from Missouri, some expeditions were truly extraordinary passages. Several very early, unauthorized expeditions were recorded between 1739 and 1751. Fur trappers and traders sought to establish regular commerce between New Mexico and settlements in Upper Louisiana—but that did not materialize. Spain protected its northern frontier from American and French intrusions. Between 1786 and 1812, New Mexicans nurtured a fragile peace negotiated by New Mexico governor Juan Bautista de Anza with a confederacy of Comanche bands living east of the Pecos River in New Mexico and east into Texas. That peace permitted Pedro Vial, an extraordinarily capable French explorer employed by Spain, to chart roads between San Antonio, New Orleans, and New Mexico. He and several New Mexicans traversed the region remarkably often in anticipation of an ultimately elusive commercial trade with Louisiana and Texas. Vial’s travels brought him to Saint Louis as well, and he is often credited with being among the trailblazers who presaged the Santa Fe Trail.

The neighborhood where I chose to make my home in Saint Louis is on a land grant made to a prominent French American fur trader named Jules DeMun and his wife, Isabelle Gratiot, during the Spanish administration of the region in the late eighteenth century. DeMun wrote about his fur-trading expeditions on streams north of Taos between 1815 and 1817, one of the first written accounts. In May of 1817, DeMun; his partner, Auguste P.Choteau, another notable Saint Louisan; and their party were arrested on charges of crossing illegally into Spanish territory. DeMun was taken to Santa Fe, where he and his party were confined in what he called a “dungeon”—probably a room or a cell in the Palace of the Governors complex—for over six weeks. An irate Governor Alberto Maynez presided over a judicial hearing in which DeMun was challenged to define and describe the boundaries of Spanish and American holdings west of the Mississippi. The judge forced the trappers to kneel and kiss the written sentence they received: they would forfeit more than $30,000 in furs and hides and be banished from New Mexico.

David Meriwether owns the distinction of being the last man to be arrested for trying to establish trade with Mexico. When he was a young man, in 1819, New Mexicans apprehended him during a skirmish between New Mexican troops and Pawnees. Historians and fiction writers have found inspiration in his spectacular capture and his imprisonment in the Palace of the Governors. Governor Facundo Melgares welcomed Meriwether to Santa Fe, then harshly ordered him and an African American servant to leave the territory late in the fall, evicting them in spite of winter’s perilous approach. As a result, New Mexico’s reputation as a place hostile to Americans, ruled by cruel and despotic governors, solidified.

New Mexico hadn’t seen the last of Meriwether. He returned to Kentucky, where he became a prominent lawyer and politician. The next time he came to Santa Fe, in 1853, he returned as the third American governor of New Mexico, serving only two years before returning to his plantation near Louisville.

Why did Missouri traders continue to try to establish a connection with Mexico? In part, they might have underestimated the hardships they could face. The possibility of new markets in the Southwest surely inspired merchants and profiteers of the trade. Bank failures in 1819, and the near collapse of the economy that came with them, pushed people to pursue otherwise unlikely ventures.

William Becknell

Meets Captain Pedro Ignacio Gallego The honorary title “Father of the Santa Fe Trail” is usually applied to William Becknell of Boons Lick, Missouri. I have visited the area around Boons Lick often, taking in the archaeological sites where salt makers like Becknell lived. Although down on his luck in the 1819 financial panic, Becknell was, in other ways, the right man, at the wrong place, at the right time. On September 1, 1821, Becknell and a party of five other men left Franklin, Missouri, bound for the Rocky Mountains. By embarking on this expedition, Becknell hoped to avoid prison for a debt of less than $500. According to his newspaper advertisement, he intended to hunt for fur-bearing animals and to trade for horses and mules.

Traveling on horses and mules, the men crossed the plains surrounded by immense herds of buffalo, and other animals that they could not identify (antelopes and jackrabbits), which provided them with some skins and hides. On October 13, at 3:30 in the afternoon, west of present-day Las Vegas, New Mexico, they met a New Mexican militia.

Becknell could not have known when he met these troops at the mountain gap known as Puertocito de la Piedra Lumbre that his party would be safe from the chains and prison cells that had beset their predecessors. Pedro Ignacio Gallego, captain of the New Mexico militia, greeted the traders with friendship and generous hospitality at the village of San Miguel on the Pecos River. Gallego appeared to Becknell to be a strict officer; his troops struck Becknell as servile. Becknell likely knew French from his time in Upper Louisiana, and there in San Miguel they met a New Mexican man who knew French and Spanish. He served as their guide and translator in their meeting with Governor Melgares.

Prior to his position as militia captain, Melgares had been the last Spanish governor of New Mexico and an explorer who had been part of a Spanish expedition to the plains in 1806. About eight weeks earlier, Melgares had taken an oath of loyalty to the Mexican government. He was still waiting for orders from the central government as to how New Mexico would be administered as a territory of an independent nation and was under no mandate to expel Becknell’s party. They arrived in Santa Fe on November 16, 1821.

Two men mentioned in Gallego’s report, José Vicente Villanueva and Juan Lucero, likely served as translators. Both career soldiers, they were veterans of dozens of expeditions to the Comanche trading groups and participants in several Spanish diplomatic missions to San Antonio and New Orleans. Lucero’s twenty-seven-year career included more than twenty crossings of the plains and several harrowing encounters with Comanches while in service to Pedro Vial. Neither Becknell’s nor Gallego’s record of that meeting is dramatic or detailed. And what a pity, because the Americans were meeting some of the most skilled traders and explorers of New Mexico. Villanueva and Lucero lived on the edge of Spanish territory in the villages of San Miguel and Pecos, and their knowledge of the country and the tribes of the Southern High Plains was immense. Did Becknell and Villanueva talk about Saint Louis, where Villanueva had spent eight months between October 1792 and June 1793, and where he recovered, along with other members of Pedro Vial’s expedition, from their capture by Kansas Indians? How unfortunate that at that moment, at the beginning of free trade between the nations, no scribe from either side recorded the exchange of geographic and cultural information.

Becknell’s risky expedition at a pivotal moment in the history of New Mexico changed his luck. He returned to Missouri with legendary profits and quickly organized a larger expedition of twenty-one men and three wagons in May 1822. Although he did not continue in the Santa Fe trade much longer, he offered wise counsel to those who did, advising them to take “goods of excellent quality and unfaded colors,” as New Mexicans would pay well for the items they needed or desired.

Becknell’s journal was terse. But in the typically florid language of the time, a piece that appeared in the Missouri Intelligencer newspaper explained the freedom of trade and other liberties offered by the New Mexican nation:

Monarchy bound in chains and threw into prison all those of our unfortunate countrymen whom accident or business brought within its reach; while republicanism extends the hand of friendship & receives them with the welcome of hospitality. The one did not wish its people to be informed by an intercourse with those of other nations, because it would enable them to comprehend the wickedness, corruption, folly and illiberty of its administration; while the other cheerfully affords the means of diffusing intelligence, knowing that it contributes to the happiness of its people, the prosperity of its institutions and the permanence of its government.

Susan Shelby Magoffin’s Journal

Another journal that I often pored over in New Mexico has come to have a deeper resonance with me—that of Susan Magoffin, the eighteen-year-old bride of Santa Fe Trail trader Samuel Magoffin. His brother, James Magoffin, was a trader of long experience on the trail, and is often credited with negotiating the surrender of New Mexico to the United States in 1846. When she embarked on the trail, Susan Magoffin left behind the comfort of her privileged life in Kentucky for the unfamiliar social and political environment of Mexico in 1846. She did so in concert with the expansion of the United States, moving west to the drumbeat of Manifest Destiny.

Her journal might have been dismissed as little more than the romantic writings of a love-smitten bride, unimportant next to the military journals and correspondence of the officers who conquered New Mexico, had it not been for the diligence of its editor. Stella Drumm was the stalwart librarian for the Missouri Historical Society from 1913 to 1944. The society’s library, where she edited the journal, is now my office.

Magoffin’s journal contains her observations and an account of her awakening to the freedom of the trail—climbing to the high points to take in the vast vistas, learning Spanish words, songs, and foodways. The low necklines and ankle-baring fashions that women wore in New Mexico scandalized Magoffin. She was appalled by their makeup and cigarette smoking, but won over by their hospitality. Her experiences on the trail prompted her to take on philosophical questions that may not have occurred to her if she had remained in Kentucky. She wondered why men went to war. She questioned her faith, then found solace in that same faith as she contemplated a death that might come from yellow fever or as a consequence of the swirling conspiracies that accompanied the US Army’s entrance into northern Mexico. At times she was impatient with the stares and whispers that her clothes and mere presence aroused in New Mexican villages.

Susan Magoffin returned from Mexico to make her home in the Saint Louis area, where she died at the age of twenty-four in October 1855, having suffered from yellow fever and a delicate constitution throughout her Santa Fe Trail travels.

The Enduring Legacy of the Santa Fe Trail

Neither DeMun, nor Becknell, nor the Magoffins stayed in New Mexico. They all went back to Missouri with tales to tell about the opportunities that awaited those who could navigate the logistics and the tricky politics at the other end of the trail. Likewise, New Mexican traders came to prosper from the trade as they formed partnerships with trading houses and suppliers, many of whom transported their wares from the docks in Saint Louis and from western ports along the Missouri River.

Becknell and Magoffin may not have been the first travelers over the trail, but each came at a significant moment in history. Becknell came just as Mexico won its long fight with Spain for independence. After a decade or more of revolts and plots, Mexico threw off the trade restrictions that had discouraged the earliest Missourians from crossing the plains. Mexican independence brought other liberties as well, allowing Missourians to find a place in that northern frontier and then to become welcomed further into the interior of Mexico—not as prisoners, but as partners in life or marriage as well as in international commerce.

Susan Magoffin’s observations are significant even in their naïveté. She witnessed those gentle and awkward, violent and vehement actions that slowly but inevitably brought the two nations and peoples of many cultures together. And so, too, I have come to see the trail from new perspectives, with a greater understanding of the ways that Missouri and New Mexico were connected by so many threads. The trail joined the fascinating history of the United States as it reached west, a culturally rich history of Native American and Hispanic traditions of the Southwest.

Frances Levine, PhD, is president of the Missouri Historical Society, Saint Louis, and the former director of the New Mexico History Museum and the Palace of the Governors.