Lives and Half-lives

Reckoning with atomic history’s local legacies

BY MELANIE LABORWIT

The Santa Fe Opera’s sense of place is extraordinary; operagoers watch world-class productions ensconced in the great outdoors, surrounded by Santa Fe’s gorgeous sunsets, stunning vistas, and starry skies. With this summer’s production of Doctor Atomic, the sense of place factor expands dramatically to include not just the scenic, but the historic and the geographic.

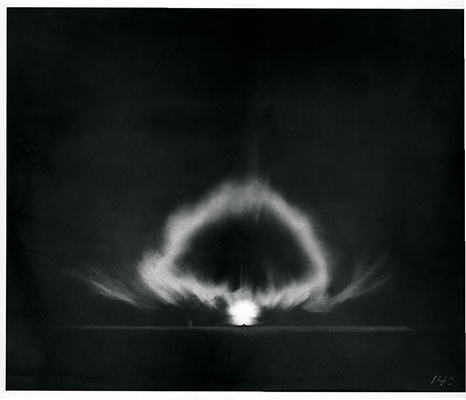

John Adams’ opera focuses on the scientists who developed the atomic bomb at Los Alamos—just thirty miles from the Santa Fe Opera—during World War II’s Manhattan Project. The story, written by acclaimed librettist Peter Sellars, follows J. Robert Oppenheimer, director of the Los Alamos Laboratory, and other scientists as they weigh moral and ethical questions about their responsibilities and the impact of their game-changing discovery. The drama unfolds in June and July of 1945, set in Los Alamos and at Trinity Site in southern New Mexico, where scientists detonated the first atomic bomb.

Atomic Histories, a New Mexico History Museum exhibition opening June 3, expands the breadth of the opera’s offering in an iteration much more accessible to the public. As part of the museum’s Tech and the West partnership with the Santa Fe Opera, the museum honors our state’s role in this pivotal geopolitical development. With a shared authority borne of a collaboration with the Los Alamos History Museum, the Atomic Heritage Foundation, the Santa Fe Opera, Los Alamos’ Bradbury Science Museum, and the National Museum of Nuclear Science and History, Grants’ New Mexico Mining Museum and the nascent Manhattan Project National Historical Park, the New Mexico History Museum assembled a wide variety of resources to tell our state’s nuclear story.

Atomic Histories focuses on the people who played a role in producing the atomic bomb in New Mexico in the 1940s, and of many New Mexicans who work in our national labs, uranium mines, and related industries. The exhibition will also share about the bomb’s lasting cultural and environmental impact on New Mexico. Visitors can map the arrival of scientists in Lamy, their stops in Santa Fe, and how the city of Los Alamos was built by workers from northern Hispanic villages and Pueblos.

The exhibition also examines the environmental impact of the detonation on small towns in southern New Mexico downwind of the original Trinity site, and the effects and legacy of uranium mining on western New Mexico’s Native communities.

From 1944 to 1986, tens of millions of tons of uranium ore were extracted under mining leases on the Navajo Nation and nearby Laguna Pueblo.

The exhibition includes the tumultuous history of uranium mining in New Mexico, the lives of miners in these communities, and the Environmental Protection Agency’s current mitigation of the risks of contamination in and around abandoned mines.

Other contemporary subject matter includes ongoing scientific research at Los Alamos National Labs and Sandia National Labs, whose scientists come from all over the world. Atomic Histories attests to the growing role of women in scientific innovation, like Cheryl Rolfer, who served for decades as the head of the toxic waste division at Los Alamos National Labs, and whose story illuminates what life was like on “the Hill” during this time.

In addition to familiar names involved in historic scientific achievement, visitors will meet many of the men and women behind the scenes of the Manhattan Project whose stories are rarely told, and will hear the voices of participants in different scientific endeavors over the last fifty years.

The exhibit also chronicles the creation of the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant in Carlsbad, its infrastructure, and how it stores nuclear waste. Visitors might be surprised to find out that tiny Eunice, in southern New Mexico, is home to URENCO, the country’s most advanced uranium enrichment facility; it’s the only one to be built in the U.S. in thirty years, and the first to use centrifuge enrichment technology.

Many of the institutions we take for granted today sprang from the atomic era. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) originated in the Cold War as part of the Office of Civil Defense. The sirens used today to notify people about impending hurricanes, fires, and floods were originally designed to be able to announce potential Soviet missiles. The end of the Cold War allowed the agency’s resources to change from civil defense to natural disaster preparedness.

In 2003, FEMA joined twenty-two other federal agencies and programs to become the Department of Homeland Security.

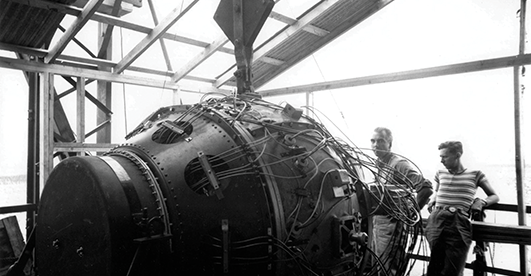

Innovations in supercomputing and satellite telecommunications, used for innumerable applications today, were originally intended to measure potential nuclear explosions and to maintain national communications. The fields of microelectronics, seismic and atmospheric measurements, computer memory, and high-speed photography all initially supported nuclear programs. Reflective of the pervasive nature of the nuclear legacy, Atomic Histories includes related artifacts from many different collections, including one of the original high-speed cameras devised for documenting the powerful Trinity test, as well as a lead brick that shielded equipment from the power of the blast. Berlyn Brixner was the head Manhattan Project photographer for the Trinity test, and his continued work with high-speed and motion photography helped to capture images of many other explosions and the dropping of dummy bombs to help the scientists better understand the science and physics behind them.

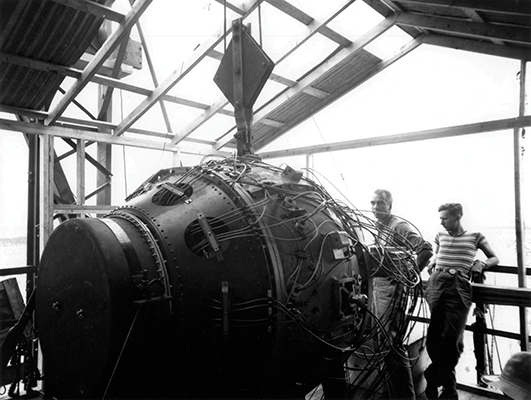

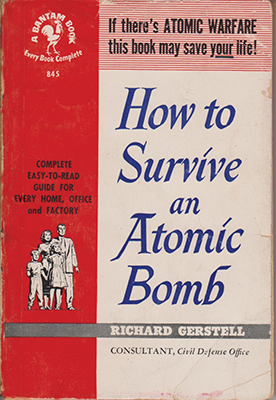

During the Cold War, Americans developed a vigilant mindset and acquired tools to protect themselves. The exhibition shares Civil Defense documents, scale models of fallout shelters, and different models of Geiger counters and dosimeters (instruments for measuring radioactive activity) including those once manufactured in Santa Fe.

In addition to scientific and historical items, the exhibition includes artists’ interpretations of the atomic legacy and its lasting impact on New Mexico. The exhibition features a selection from artist Meridel Rubenstein’s Critical Mass, a mixed-media installation made up of glass, photographs, video, and steel. Critical Mass examines the cultural crossroads found in station agent Edith Warner’s train station/tearoom/home, popular with both Los Alamos scientists and residents of neighboring San Ildefonso Pueblo.

In July 1995, SITE Santa Fe opened its first biennial on the 50th anniversary of the first atomic test at the Trinity Site. Rubenstein’s pieces The Meeting and Oppenheimer’s Chair were commissioned for that opening, and are also part of Atomic Histories.

Finally, inquiring minds of all ages will be invited to master scientific ideas like What is radioactivity, anyway? and How do you measure this naturally occurring energy? in hands-on ways. We’ll share about the tools Los Alamos human computers used to calculate the mathematical equations, and new inventions created to further atomic research.

Atomic Histories presents seldom-seen views of the Manhattan Project at the same time that it highlights how these phenomenal discoveries continue to impact the present and future. Many questions remain, but there’s no doubt that when it comes to reckoning with this epic topic, New Mexico is the most apt place to do so.

Melanie LaBorwit is an educator at the New Mexico History Museum and the Palace of the Governors.