Coyota

Juana Domínguez: A Woman Between Two Cultures

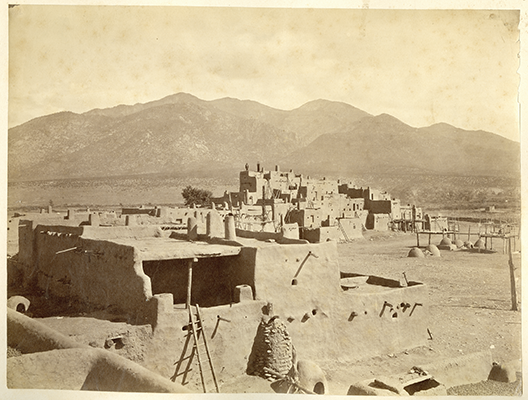

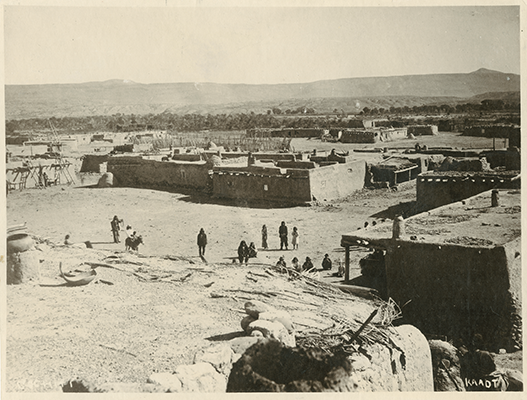

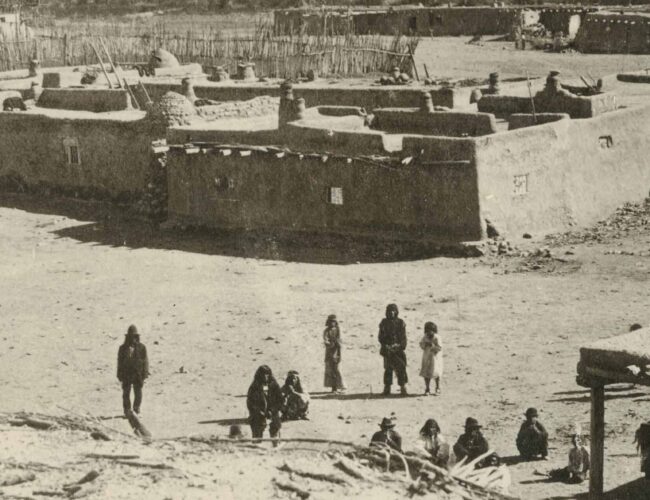

View of Cochiti Pueblo, New Mexico, ca.1879–1880. Photograph by John K. Hillers. Courtesy Palace of the Governors Photo Archive (NMHM/DCA), Neg. No. 002493.

View of Cochiti Pueblo, New Mexico, ca.1879–1880. Photograph by John K. Hillers. Courtesy Palace of the Governors Photo Archive (NMHM/DCA), Neg. No. 002493.

BY JOSÉ ANTONIO ESQUIBEL

Pueblo Indians and Hispanos of New Mexico share common bonds forged over the course of more than four hundred years. During those centuries, there were more years of cooperation and co-existence, punctuated with episodes of conciliation, than years of conflict. Each group influenced the cultural history of the other, which is evident in historical records as well as in our own time. Additional evidence is appearing in the DNA results of New Mexico Hispanos. Eighty-five percent of Hispano males participating in the New Mexico DNA Project have maternal DNA that indicates Native American genetic ancestry. This means that many Hispanos of New Mexico and many Pueblo Indians share ancient common ancestors and an ancestral history reaching back thousands of years.

There are fragments of information found in archival records that, when combined, offer insights into the familial bonds that existed in the past between some Hispanos and Pueblo Indians. The story of Juana Domínguez is one intriguing example of an individual with familial ties to a Pueblo Indian community and who lived as a member of a Spanish community. Her descendants live in New Mexico today, and in many other regions of the United States.

At the Hour of Death

January 12, 1717. The cold of winter settled over the small Villa de Santa Fe. Adobe houses dotted the landscape nestled along the foothills of the nearby mountain range. The houses spread out from the main plaza parallel to and straddling the Santa Fe River, forming a constellation of dwellings with small orchards and fields for planting.

At one of the houses in the area of modern-day Water Street, Juana Domínguez lay ill in bed. Knowing death approached, she reflected on her life from the time of her early childhood at Taos Pueblo to her marriage with Domingo Luján, her capture during the Pueblo Indian uprising of August 1680, her eleven years living among Pueblo people, her return to life among Spanish citizens with her children in 1692, her thirteen years as a widow, then eight years as the wife of town councilman Lorenzo de Madrid, and her final years as a landowner and grandmother.

At the request of Juana’s family, Salvador Montoya, the alcalde mayor, chief magistrate of the town, entered Juana’s home with two other officials, Bentura de Esquibel and Juan de Medina. As was customary, it was a duty of the alcalde mayor to record and notarize last wills and testaments of citizens.

With family members and the officials at her bedside, Juana dictated her last will beginning with affirmation of her Catholic faith and then stated:

I order that my body be buried in the Chapel of Our Lady of Rosary, La Conquistadora. I request my body be dressed in the habit of our Seraphic Father, St. Francis. I also declare that a funeral mass be said with a vigil and that they say three masses for which I request that my son, Juan Luján, pay for.

She identified debts owed to her in the amount of seven pesos and seven pairs of stockings. Her debts amounted to two pesos, eight pairs of stockings, and two horses that she owed others. She further declared:

I was married and veiled according to the rites of our Holy Catholic Church the first time with Domingo Luján and we procreated one son and three legitimate daughters, Juan Luján, Antonia Luján, Josefa Luján, and Leonor Luján. I also declare that I was married a second time to Field Commander Lorenzo de Madrid from which we had no children.

Much of her personal belongings she bequeathed to her granddaughter, Josefa Quintana, including a scarlet cape, a silk handkerchief, three yards of flowered Rouen linen, an iron griddle, a chocolate pot, a bed with a mattress, four blankets, and a pillow.

Juana declared that Domingo Luján left to her the house in which she lived and its land, which she bequeathed to her son, Juan Luján. She also mentioned land she owned in the jurisdiction of Santa Cruz de la Cañada, which she left to be divided equally among her three daughters.

Beyond her personal items and lands, the legacy of Juana Domínguez rested on her resiliency as a woman of European and Pueblo Indian ancestry and in her progeny—her children, grandchildren, and numerous descendants in New Mexico to the present day. In her life she integrated Spanish and Pueblo Indian cultures, making her distinctively a woman of New Mexico.

Almost sixty years after her death, she was still remembered. In June 1775, eighty-two year-old Juan Candelaria clearly recalled Juana Domínguez as being a coyota of Taos Pueblo when he was a witness in the prenuptial investigation of one of Juana’s granddaughters.

Mestizaje and Blended Cultures

The arrival of Spaniards in New Mexico in 1598 initiated a period of political tensions and concessions with Pueblo Indians and nomadic tribes of Navajo and Apache, but also among and between the Spaniards.

The conflicts within Juan de Oñate’s army resulted in a large number of the soldiers leaving New Mexico within a decade of their arrival. By 1609, there remained only about fifty men, some with families, defending a small group of Franciscan friars. A few of these men, including the friars, were among the first of European ancestry to father children with Pueblo Indian woman. The offspring of these unions were often identified as coyotes.

Some coyotes were raised within Pueblo Indian communities, adopting traditional tribal customs. Others lived among Spanish citizens, where they acquired Spanish language and customs, but also kept in touch with Pueblo Indian relatives and were often bilingual.

By the second half of the 1600s, there was a segment of Spanish citizens with relatives among Pueblo Indian communities and vice versa. This constellation of family groups crossed cultural boundaries, creating a distinctive population that blended both cultures and were connected by familial bonds.

There is no physical description of Juana Domínguez and we do not know the year of her birth. Although there are no records to inform us about Juana Domínguez’s early life, it is known that she was the sister of a mestizo named José Domínguez de Mendoza, born circa 1658, who lived among the Spanish citizens and became a soldier of distinction. His mother was an Indian woman named Ana Velásquez who served as a cook and laundress at the casas reales, the royal government building and house of the governor in the Villa de Santa Fe.

Ana Velásquez was a native of the Villa de Santa Fe and married an Indian man named Francisco Cuaxinque. She was most likely not the mother of Juana Domínguez. Instead, Juana and José probably shared the same father. Their surname of Domínguez offers a clue as to their paternity: Their father may have been a male member of the prominent Domínguez de Mendoza family of New Mexico.

Tomé Domínguez, a resident of Mexico City, first came to New Mexico in the 1630s as a merchant conducting business with Franciscan friars. By 1636, he was serving as a squadron leader in New Mexico and soon after he brought his wife, Elena de la Cruz y Mendoza, and several children to live in the frontier realm. Among these children were three grown sons, Tomé Domínguez de Mendoza, Juan Domínguez de Mendoza, and Francisco Domínguez de Mendoza.

By 1677, Juana Domínguez became the wife of Domingo Luján, a mestizo born circa 1655. She very likely wed sometime between the ages of twelve and fifteen, as was customary for females of her era. Although the parentage of Domingo Luján is also unknown, he was apparently a member of the Luján family established in New Mexico by Juan Luján, a native of the Canary Islands who arrived in New Mexico in 1600. The first several generations of the Luján family of seventeenth-century New Mexico were identified as mestizos, indicating a combination of Indian and European ancestry.

Like his wife, Domingo Luján had relatives among the Pueblo Indians, including a brother known only as “El Ollita,” who was later regarded as one of the prominent leaders of the Keres people at Cochiti Pueblo during the uprising of 1680. This familial connection to the Keres tribe suggests that Domingo may have been a son of Francisco Luján, the alcalde mayor of the Cochiti jurisdiction in the Keres region.

Despite the lack of confirmation about Domingo’s parentage, he and Juana Domínguez shared a similar bicultural experience. Both spoke Spanish and very likely spoke at least one Pueblo Indian language. Like Domingo, Juana Domínguez probably had Pueblo Indian relatives, but her relatives were Tiwa Indians at Taos Pueblo.

Juana Domínguez bore four children by Domingo Luján in quick succession between 1677 and 1680: Antonia, Juan, Josefa, and Leonor. Many years later their son, Juan Luján, declared he was a native of the Villa de Santa Fe, so Domingo and Juana must have resided in the capital for at least a short period of time. Leonor would later declare she was born in the Río Abajo region, perhaps in the Cochiti area.

The lives of each member the Luján-Domínguez family faced dramatic changes with the fierce uprising of Pueblo Indians in August 1680.

Turmoil, Trauma, and Capture

As Juana Domínguez entered adulthood, threatening challenges impacted the lives of Spanish and Indian residents during the 1670s and influenced the course of New Mexico history.

Consecutive years of severe drought in the late 1660s produced low yields of maize, wheat, beans, and squash. The harsh winters killed weak livestock. Diminished food supply led to famine among Pueblo Indians and Spanish citizens, aggravated by pestilence and followed by death from starvation. In June 1669, Governor don Juan Medrano Messia lamented, “The land is so impoverished as a result of such great famine and misfortunes.”

To stem starvation, it was reported that Spanish citizens and Pueblo Indians ate leather hides, soaking them and then toasting them with fire with whatever supply of maize was available, and boiled the combination with herbs and roots.

The harsh climate conditions and food shortage compelled nomadic tribes of Navajo and Apache to increase their raids on Pueblo communities and Spanish ranches. Repeated incursions by these raiders carried off Pueblo Indian women and children captives, as well as numerous head of livestock.

Fray Francisco de Ayeta described the devastating impact of the unrelenting and ferocious raids when in 1679 he informed officials in Mexico City, “It is public knowledge that from the year 1672, six pueblos were depopulated.”

According to de Ayeta, on one occasion, “The Apache enemies hurled themselves on the Pueblo of Acoma and killed twelve persons of the said pueblo, carried off two women alive, eight hundred head of sheep and goats, sixty head of cattle, and all of the horses that were in the pueblo.”

Following such attacks, governors organized military campaigns in retaliation and to reclaim captives and livestock. These campaigns usually involved a force of only forty to fifty soldiers and anywhere from two hundred to six hundred Pueblo Indian warriors, a clear indication of the cooperative relationship that existed for decades between Spanish officials and Pueblo Indian leaders.

Throughout the 1600s, Pueblo Indian fighters consistently outnumbered the few Spanish soldiers. In 1678, there were only 120 Spanish citizens that bore arms, including the addition of almost fifty men soldiers sent from Mexico City in early 1677 to assist with defending the region. This small population of Spanish citizens was surrounded by thousands of Indians, including bands of Apache, Navajo, Hopi, and Ute, as well as numerous Pueblo Indian tribes allied with the Spanish government.

Without the confederacy of Pueblo Indians as allies, the Spanish citizens could not have remained in New Mexico. So confident were Spanish officials about their alliance with Pueblo Indian leaders that they did not suspect or expect a general uprising on the part of the allies. In the 1670s, Spanish officials were more concerned about having to abandon New Mexico because of attacks on Pueblo and Spanish communities by nomadic Indian groups.

The conditions of a decade-long drought followed by famine and starvation, coupled with the distress from Apache and Navajo raids, frayed the social and political fabric of the Pueblo-Spanish alliance, creating fertile conditions for grievances to be transformed into an organized uprising by leaders of the northern Pueblo communities.

In the aftermath of the uprising, Pueblo Indians explained to Spanish government officials that their main grievance stemmed from the violent treatment by three officials of the Tewa jurisdiction against Pueblo Indian religious leaders and vindictive means of suppressing traditional religious ceremonies. Acting under orders of Governor Antonio de Otermín, Francisco Xavier, the magistrate of the northern jurisdiction, and his two aides—Luis de Quintana, his secretary, and Diego López Sambrano, an interpreter—confiscated Pueblo Indian religious objects, burned kivas where ceremonies were held, and relentlessly persecuted Pueblo Indian religious leaders.

Spanish officials regarded the Pueblo ceremonies as sorcery and idolatrous. Their particular targets of chastisement were El Popé and El Taque of San Juan, Saca of Taos, and Francisco of San Ildefonso. These leaders fled to Taos Pueblo from where they planned a campaign to unite Pueblo communities with the goal of ridding the region of the Spaniards.

Throughout the first seven decades of the 1600s, Pueblo Indians did not live in helpless resignation under the authority of the Spanish government. Many Pueblo Indian leaders sought benefits to the well-being, safety, and prosperity of their people by entering into an alliance with Spanish government leaders. They acquired and retained self-governance within their own communities while also cooperating in joint commercial and economic activities, as well as accepting Franciscan friars into their communities.

From the time the Spaniards entered New Mexico in 1598, there were always factions within various Pueblo communities that disagreed with the policy of accepting Spanish governance and desired to return to the traditional ways of their people. It was under the conditions of severe drought of famine and increase attacks by hostile bands of nomadic Indians in the 1670s that those factions gained an edge in political power.

Among the northern Pueblo communities, leaders who maintained cooperative relations with the Spanish government fell out of favor with their people. El Popé and his supporters managed to shift the sentiment among the Pueblo populous and attained political prominence. Unified by shared grievances against Spanish government authority and the suppression of their religious traditions, multiple Pueblo communities joined the cause.

The uprising of August 1680 unfolded with nearly complete surprise to Spanish citizens. Following the tragic death of numerous men, women and children, and the burning of homes and ranches, the surviving citizens fled south. A number of individuals, mainly women and children, were taken captive, including Juana Domínguez and her young children. Their lives were probably spared because of her familial Pueblo connections. Her husband was traveling outside of the kingdom on military duty and may very well have thought that his entire family was killed during the uprising.

Survival, Rescue, and a New Life

Juana’s and her children’s lives changed dramatically. The Pueblo Indian uprising was not just an instance of retribution by one group of people against another; the astounding event also tore families apart. An entire segment of New Mexico’s population that straddled cultural boundaries became separated. Parents, siblings, aunts, uncles, cousins, and grandparents lost contact with one another.

In the early days following the uprising, perhaps Juana held hope that Spanish and Pueblo Indian leaders would reach an agreement of reconciliation and that she would be reunited with her husband.

Such hope almost came to fruition when Field Commander Juan Domínguez de Mendoza led an expedition in November 1680 from El Paso del Norte to as far north as Cochiti Pueblo. At Cochiti, Domínguez de Mendoza nearly succeeded in restoring peace in negotiations with Pueblo Indian leaders, including Alonso Catiti, a coyote who was the brother of the Spanish soldier Pedro Márquez.

Domingo Luján accompanied Domínguez de Mendoza. At Cochiti, Luján gave some gunpowder to his Pueblo Indian brother, El Ollita, who requested the powder for defense against the Apache. This action was in direct violation of an order given by Domínguez de Mendoza to not provide gunpowder to the Pueblo Indians. Faced with threat of execution as “a traitor to God and king,” Luján confessed to providing one charge of gunpowder from his own pouch. He avoided death with his forthright and honest confession. His action illustrates that a strong familial bond still existed despite the conditions of war.

The promise of reconciliation evaporated when Governor don Antonio de Otermín burned the pueblos of Alameda and Sandia as a strategy of retribution while on his way to join Domínguez de Mendoza. This vengeful action shattered the peace negotiations and solidified twelve years of exile of the Spanish citizens at El Paso del Norte.

Juana Domínguez and her children remained among the Pueblo Indians. She was apparently passed along to relatives at Taos Pueblo, where she very likely spent the next eleven years as a resident. She probably lived less as an imprisoned captive and more as an integrated member of the community that probably included relatives, but she was still not free to leave to join her husband. She and her children would have adopted Pueblo Indian ways in a very short time, including the adoption of the Tiwa language, clothing, and hairstyle, as well as social and religious customs.

If her sense of hope in reuniting with her husband waned over the years, news in 1692 that Governor Don Diego de Vargas entered northern New Mexico and negotiated peace with Pueblo Indian leaders likely rekindled the flame of that hope.

De Vargas relied heavily on soldiers of his army with relatives among the Pueblo people in his diplomatic efforts. Of particular value were those soldiers who spoke Keres, Towa, Tano, and Tewa, and served as cultural brokers.

Among those who assisted de Vargas in the successful reconciliation was Sargento Mayor Miguel Luján, who enlisted the assistance of his relatives among the Tewa and Tano Indians of northern New Mexico. One very influential relative was his niece, the wife of Luis Tupatú, the main leader of northern New Mexico’s Tewa Indians and who was also among those who led the uprising of 1680. In 1692, Tupatú and Governor de Vargas orchestrated peace, which reinstated Spanish governance and self-rule within Pueblo communities, and allowed the Spanish settlers to return to northern New Mexico.

Several individuals that were taken captive in 1680, including Juana Domínguez and her children, were rescued in October 1692 as a result of this remarkable reconciliation.

On October 9, 1692, Governor de Vargas made an entry in his military journal indicating that the Taos Pueblo leaders “turned over their captives, two women with seven children of all ages.” While encamped at the hacienda de Mejía in the modern-day area of Albuquerque on October 29, the governor ordered a written account of the rescued captives. At the top of the list was Juana Domínguez with four daughters and one son who were taken in the custody of her brother, José Domínguez de Mendoza. We can only imagine the emotions when Juana and the children reunited with Domingo Luján at El Paso del Norte.

The successful restoration of New Mexico to the Spanish crown was underscored by reconciliation between family members who bridged cultural boundaries between Pueblo Indian society and Spanish society. Family members long separated were reunited, such as the case of Sergeant Juan Ruiz Cáceres, a brother-in-law of Miguel Luján, who took with him to El Paso del Norte two Indian cousins named Tomé and Antonia to rejoin other family members.

The task of achieving peace and stability in frontier New Mexico among the diverse Pueblo Indian communities and with the Spanish citizens was formidable and required several years of constant effort by Pueblo Indian and Spanish leaders. Principal Indian leaders included Don Luís Tupatú of San Juan, his brother Don Lorenzo of Picurís, Domingo Tuguaque of Tesuque, Bartolomé de Ojeda of Zia, Cristóbal Yope of San Lázaro, and Don Juan de Ye of Pecos. These men diligently strove to overcome distrust in resolving conflict. The accords of peace negotiated with don Diego de Vargas set a foundation for the future course of New Mexico’s history and cultural development.

This reconciliation also reset the life course of Juana Domínguez.

Widow, Landowner, and Matriarch

Governor de Vargas organized a large group of former residents of northern New Mexico who were willing to help reestablish the Villa de Santa Fe. Moving slowly northward from El Paso del Norte in October 1693, the settlers and their wagons arrived at the outpost of Fray Cristóbal along the Rio Grande at the northern edge of the Fray Cristóbal mountain range.

In this area, during the late afternoon of October 31, Domingo Luján, serving as a soldier, gave chase to a stray cow. In the scurry of the chase, his horse collided with the animal. The horse lost balance and toppled onto Domingo, knocking him unconscious. He must have suffered a severe head injury; by midnight, as Governor de Vargas recorded, “Our lord saw fit to take him away.” Juana Domínguez was now a widow after a short-lived reunion with her husband.

Juana could have returned to the relative safety of El Paso del Norte. Instead, she remained resolved to settle at the Villa de Santa Fe with her children. By 1696, she received a grant of land in Santa Fe, and in May 1697, she was listed as a recipient of livestock distributed to settlers. In her household were four children: Juan, Josefa, Leonor, and María. Antonia was not listed.

Juana’s land was located along the Rio Chiquito, the modern-day area of Water Street. She sold a portion of her property to Sergeant Bartolomé Lobato in August 1701 and retained a portion of land that was eventually inherited by her son.

As early as 1697, Juana developed an intimate relationship with Lorenzo de Madrid, one of New Mexico’s leading military and civic leaders. The relationship drew public scrutiny and the accusation of living in scandal with this man. They were wed a decade later in the Villa de Santa Fe on July 10, 1707, with Antonio Godines and María Domínguez de Mendoza as witnesses.

In the course of the prenuptial investigation prior to her marriage to Lorenzo, witnesses testified that Juana Domínguez was “a captive at Taos” along with a woman named Magdalena Domínguez and this woman’s daughter, María Domínguez. Following the death of Magdalena, Juana raised María, who was apparently the fourth child listed in Juana’s household in May 1697.

Lorenzo de Madrid served numerous terms on the town council of the Villa de Santa Fe. He died in 1715, bequeathing his land and house to Juana, and appointing her son, Juan Luján, as the administrator of his estate.

Juana’s extended kinship network in the Villa de Santa Fe included her brother, José Domínguez de Mendoza, and his family, as well as her Luján family in-laws. Whether she maintained contact with any relatives or friends at Taos Pueblo is not known.

In the final years of her life, Juana Domínguez presided as the matriarch of a growing extended family of her own. Her daughter, Antonia Domínguez Luján, married José de Quintana, a native of Mexico City. Josefa Luján first married Matías Martín, a New Mexico native, and then married Melchor de Herrera, a native of Guanajuato. Leonor Luján became the wife of Cristóbal Varela, also a native of New Mexico. Juan Luján married María Martín and their marriage lasted forty years. Through each of her children, Juana Domínguez has countless descendants living today.

Fuerza, Strength

Like other women of her era, fuerza is a Spanish word that well characterizes Juana Domínguez. Meaning strength, it is a feminine word that connotes force, power, and firmness. As a word of being rather than a word of action, fuerza emphasizes that strength is more importantly manifested in spirit and determination. Through the force of her character as a woman, a sister, a wife, a mother, an aunt, a grandmother, a widow, a landowner, a relative of Pueblo Indians, and as a Spanish citizen, Juana Domínguez is distinguished as an individual whose identity and life was shaped by the heritage of two cultures of New Mexico.

If her wish to be buried in the Chapel of Nuestra Señora del Rosario, La Conquistadora, was fulfilled, then her bones lay today beneath that chapel within the Cathedral Basilica of St. Francis of Assisi in Santa Fe.

José Antonio Esquibel is co-author with France V. Scholes, Eleanor B. Adams, and Marc Simmons of Juan Domínguez de Mendoza: Soldier and Frontiersman of the Spanish Southwest, 1627–1693 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2012). He is also author of “The Tupatú and Vargas Accords: Orchestrating Peace in a Time of Uncertainty, 1692-1696,” published in El Palacio, Spring 2006, Vol. 111, No. 1.

The Story Behind the Story

BY SHELLEY THOMPSON

Several years ago, on a sun-dappled afternoon in an upstairs conference room at the Udall Building, a team of museum outreach and education specialists met to brainstorm about an upcoming exhibition on the Van of Enchantment (now known as Wonder on Wheels). Our topic was how to effectively tell the story of El Camino Real in a very small space. During our discussion, former Van of Enchantment coordinator Amanda Lujan mentioned that her family came up the trail with Onate’s settlers in 1598. My head popped up from the notes I was taking.

“Really? How do you know that?” I asked.

“It’s what I’ve always been told,” she replied.

Amanda supplied me with some “who begat whom” starter information, and after a few hours of highly amateur research on ancestry.com, I came up with a probable paternal lineage that traced Amanda’s family back 13 generations to Oñate’s colonization. Amanda was right.

Additional research determined that her branch of the Lujan family left their footsteps all over New Mexico history, with compelling imprints every step of the way. Of those many rich stories, this one fascinated me the most. I asked historian and subject expert José Antonio Esquibel to take the reins, expand on, and write about his findings. He did so with his usual excellence.

In our country, women have often played integral and unsung roles in forging connections between generations and among our communities, our religions, our ethnic and tribal identities, and our ability to live together through calamity and prosperity. Juana is a shining example of how that played out in the Pueblo Revolt and post-Revolt colony of northern New Spain. She is a mujer after my own heart.

Shelley Thompson is the marketing director of New Mexico’s Department of Cultural Affairs, and the publisher of El Palacio.