More Than Words

A yarn-bombing love brigade celebrates caring about veterans ... tangibly

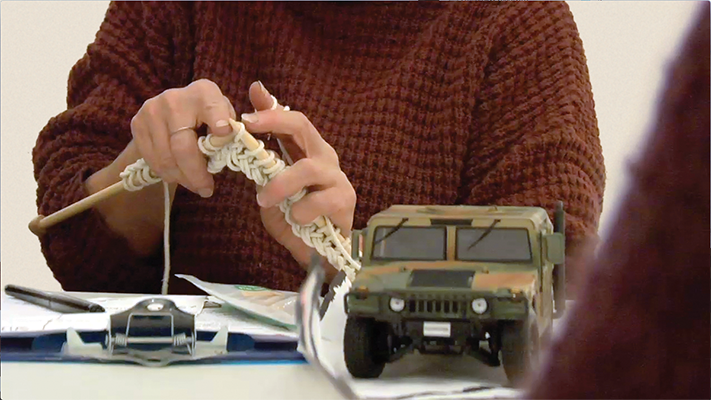

Floating Love Armor Humvee Cozy (rear view) during the 2008 exhibition at CCA. Photograph by Wendy McEahern.

Floating Love Armor Humvee Cozy (rear view) during the 2008 exhibition at CCA. Photograph by Wendy McEahern.

BY PETER BG SHOEMAKER

Ten years ago, Shirley Klinghoffer launched her seminal Santa Fe-based Love Armor Project, an effort to demonstrate the power of art to heal and to comfort the country’s warriors. Now eighteen years into America’s second-longest war, she thinks it’s time to do it again. “People can’t forget what’s going on over there, and more importantly, who is going over there,” she says.

The artistic heart of Love Armor—in 2008 and now—is a hand-knitted protective cozy for the iconic Humvee. Ten years ago, Klinghoffer and her collaborators, recognizing the meditative and therapeutic qualities of knitting, recruited fiber artists from across the country to contribute panels, that, when sewn together, fit like a cozy over the two-and-a-half-ton vehicle. New Mexico soldiers took part in the unveiling of the cozy at the Center for Contemporary Arts (CCA), and the event made national and international news.

Love Armor 2018 acknowledges the shifting and expanding landscape of caring for those who choose to fight the nation’s battles. “I’m against all wars,” Klinghoffer says, “but when people put their lives on the line, that I’m all about.” In addition to the “incendiary” anger that gave birth to the original project ten years ago—when she heard that men and women were being killed by roadside bombs because their vehicles weren’t armored—there’s something else. Her father, who grew up in a Polish shtetl and fled to the US, joined the army like so many others seeking to return the gift of refuge with that of service, and went on to fight in the waning days of World War II.

Tens of thousands of New Mexicans have served, and continue to serve, in the military. But such efforts are ones of profound sacrifice—of the bodies and minds of those that serve, and of their families. Klinghoffer originally envisioned Love Armor as a way to provide comfort, support, and understanding to those communities.

And that mission continues with the tenth-anniversary celebrations. Funded in part by a grant from the McCune Charitable Foundation, the Love Armor 2018 exhibition offers workshops focusing on advances in neuroscience and art therapy, fiber arts, social justice, and interview training by the Library of Congress’ Veterans History Project. Multidisciplinary artistic statements and conversation-starters, including a performance by Acushla Bastible, add depth and meaning to serving in the military, a choice that still only 0.4 percent of Americans (as active military) make.

The central location of the tenth-anniversary project is the former tank garage and motor pool of New Mexico’s National Guard, which for the last ten years has served as CCA’s main exhibition space. It was also the site where every serving New Mexico soldier during World War II took either the oath of enlistment or office.

“Even in New Mexico, people don’t realize we have this vibrant relationship with the military. Through it you can begin to understand the true diversity of the people who have fought for this country,” Klinghoffer says, emphasizing the experiences of Anglos, Hispanics, Native Americans, African Americans, and LGBTQ soldiers.

A CCA neighbor, the New Mexico National Guard Bataan Memorial Museum property, is managed by New Mexico’s Department of Cultural Affairs. This partnership between the state’s military and cultural organizations is more than one of convenience. It represents a close bond between the military and the state’s cultural identity, and a shared understanding of the role the military has played and continues to play here.

New Mexico is the home of the so-called Battling Bastards of Bataan—the 200th and 515th Coast Artillery—all of whom left from the compound that now hosts the CCA, and very few of whom returned from the Philippines after the horrific forced Bataan Death March and its aftereffects. This year, the New Mexico Military Museum, adjacent to CCA, added an exhibition of First World War letters, photographs, and film, called World War I 1918: The Year of the Doughboy. And the New Mexico History Museum is commemorating the centennial of the Armistice with an exhibition opening on November 11, 2018. The world’s first atomic bomb was developed in Los Alamos and tested at what is now known as the Trinity Site in the Jornada del Muerto Valley near Alamogordo, the focus of New Mexico History Museum’s Atomic Histories exhibition (up through May 31, 2019).

Phyllis Kennedy, a program coordinator at New Mexico Arts, says she was struck by the surprise many veterans expressed that “somebody cared about them.” And while there is a federal arts in the military program as well as state programs elsewhere, Kennedy is pleased that “we’re doing things our way—like Love Armor—face to face, New Mexico-style.”

Peter BG Shoemaker, a former Marine, is a frequent contributor to the magazine.