Story Tellers in Glass

Indigenous glass art fuses contemporary aesthetics and traditional values at the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture

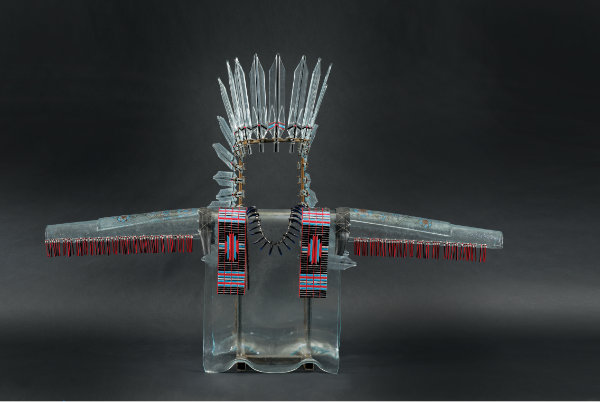

Rory Erler Wakemup (Minnesota Chippewa), Ghost Shirt, 2014. Glass and rebar. 34 ½ × 51 ½ × 18 in. Accession/catalog no. CHP-187, collection of the IAIA Museum of Contemporary Native Arts. Photograph by Eric Wimmer. Courtesy the IAIA Museum of Contemporary Native Arts.

Rory Erler Wakemup (Minnesota Chippewa), Ghost Shirt, 2014. Glass and rebar. 34 ½ × 51 ½ × 18 in. Accession/catalog no. CHP-187, collection of the IAIA Museum of Contemporary Native Arts. Photograph by Eric Wimmer. Courtesy the IAIA Museum of Contemporary Native Arts.

By Dr. Letitia Chambers

Clearly Indigenous: Native Visions Reimagined in Glass is a groundbreaking exhibition of works in glass by Indigenous artists. Co-curated by Dr. Letitia Chambers and Cathy Short (Citizen Potawatomi) and on view at the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture in Santa Fe through June 22, 2022, the stunning art in the exhibit embodies the intellectual content of Native traditions expressed in glass. A companion book of the same name (Museum of New Mexico Press, 2021) tells the story of how glass art came to Indian Country and provides information on the American Indian artists who work in the medium of glass and the processes and methods they employ in creating glass art.

Story Tellers in Glass: An Exhibit Overview

The exhibition presents glass art made by twenty-nine Native artists from twenty-six tribes from the U.S. and Canada, as well as artworks by Dale Chihuly, who founded several teaching programs where Native American students learned the art of working with glass. Native American glass artists have also collaborated with Indigenous artists from Pacific Rim countries, and glass creations by two Māori artists from New Zealand and two Aboriginal Australian artists are also included in the exhibit and the book.

The stunning pieces of glass art in this exhibition document the fusion of the Contemporary Native Arts and the Studio Glass Art movements. This fusion forms a new genre of glass art, characterized by the intellectual content of Native traditions and expressed using the properties that can be achieved by working with glass. While the book is organized around the artists, the exhibition is organized around the subject matter of the works of arts, highlighting the traditional iconography embodied in these works in the contemporary medium of glass.

The artists and artworks featured here in El Palacio provide only a brief experience of the total exhibit, which includes over 130 works of art. Images of only a few of the many fascinating works of art referenced in this text are pictured here.

Inspiration for Native glass art has come from multiple sources. It may be tribal utilitarian items, such as vessels and baskets, or it may come from a reach back into mythology, creation stories, ancient imagery, and oral history. It is often an interpretation of cultural heritage, a way of honoring and giving voice to ancestors. Other works incorporate important cultural ways of knowing, such as respect for flora and fauna.

Native glass art may also be an expression of more contemporary issues affecting today’s Native Americans and/or society at large. Some works in the exhibit include a political dimension that incorporates references to important stories in history or are a reaction to current events, while other pieces are notable for their advocacy role.

Pueblo Pottery Recreated in Glass

Tribal functional items, such as ceramic pots or baskets woven from natural fibers, represent artistic traditions still followed by glass artists. Pueblo peoples of the southwestern United States have created utilitarian vessels made of clay for millennia. Historic pots and other vessels can be found in museum collections and are admired not only for their utility, but also for their artistry. In the twentieth century and continuing to the present, traditional pottery forms made by contemporary Pueblo potters have been appreciated for both their beauty and the cultural continuity they represent.

Tony Jojola (Isleta Pueblo), untitled, 2014. Blown glass with silver stamps. 8 1/10 × 74/5 in. MIAC Collection: 59229. Photograph by Kitty Leaken. Courtesy the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture.

Several Pueblo artists have chosen to work in glass as their primary medium of creation. Tony Jojola (Isleta Pueblo), one of the first Native artists to work in glass, finds inspiration in the Pueblo pottery with which he grew up. While the forms he creates are rooted in tradition, he infuses his glass art with beautiful colors to create vivid, luminous vessels. Jojola inherited his grandfather’s jewelry-making tools and silver stamps, and he has used the stamp on some of his glass vessels.

The glass vessels created by Robert “Spooner” Marcus (Ohkay Owingeh) are rooted in Pueblo tradition, and the striking range of colors and the light emanating through his pieces in the exhibit are particularly beautiful. Recently, Marcus started a series of vessels inspired by a book on a collection of ancestral Puebloan pottery. Many of the items in the collection were pieced together from shards, with the lines from their reassembly still visible, a look which Marcus has recreated in glass. To several of the vessels in this series, he added a ladder to represent Pueblo kiva entrance ladders. While Marcus often makes vessels, his love of experimentation has also led him to create sculptural forms, such as a clear glass replica of a Pueblo on a granite base, with a ceramic pot set at the entrance.

9 × 20 ¼ × 7 in. Photograph by Russell Johnson. Courtesy Preston Singletary Studio.

Several notable Pueblo potters, who generally work with clay, have collaborated with Tlingit glass artist Preston Singletary to create works of art that incorporate Pueblo pottery designs onto blown glass vessels, including Tammy Garcia (Santa Clara), Jody Naranjo (Santa Clara) and Harlan Reano (Kewa Pueblo).

For example, Garcia began a collaboration in 2005 with Singletary to transform her pottery designs into glass. Using Garcia’s designs, Singletary and his team blew glass bowls, which Garcia then carved. These vessels are stunning in their representation of Santa Clara pottery, with the medium of glass adding a luminescence that enhances the visual impact. Famous for making black pottery in the Santa Clara tradition, Garcia created a series of black pots in glass. Garcia and Singletary have worked together on several occasions, and other glass vessels from these collaborations demonstrate the depth of color characteristic of glass.

Basketry of Northwest Coast Tribes Re-Envisioned in Glass

Tribal peoples of the North American Pacific Coast historically made utilitarian vessels of barks, grasses, or woods. Traditional baskets and bags were made of natural fibers after a painstaking process of collecting and preparing the materials so that they could be woven into useful vessels. Artists from Salish, Tlingit, Lummi, and other Northwest Coast tribes have reinterpreted baskets and bags in blown and woven glass.

Dan Friday’s understanding of his Lummi culture was influenced by Lummi artist Fran James, a master basket weaver who worked with cedar, cherry bark, and bear grass. To honor the importance of weaving in the Lummi tradition, Friday created a series of baskets woven in glass, which he entitled Aunt Fran’s Basket, in homage to James. To make his striking glass baskets, Friday groups glass rods of varying colors, and then he pulls them together into a bundle, which he fuses with a torch. The bundle is placed in a furnace to create molten glass, which he then blows into a vessel. This creates the effect of the crisscross of the traditional woven cedar baskets that inspired him.

Raya Friday (Lummi), like her brother Dan, also makes glass baskets, as does Haila Old Peter (Skokomish/Chehalis), a well-known basket weaver who in recent years has begun creating baskets in glass that mirror her grass and cedar basket designs. Alano Edzerza (Tahltan) has carved stunning glass boxes. These and the other artists featured in this section of the exhibit have based their glass art on the baskets, bags and boxes made of natural fibers and woods in their tribal homelands in the Pacific Northwest.

Textiles Recreated in Glass

Textiles have been woven in the Americas for over 12,000 years using natural plant fibers and coats of animals. Traditional spindle whorls for making threads have been created in glass by several artists, notably by Susan Point (Musqueam). In the southwestern United States, fabrics were historically woven of cotton and wool; Carol Lujan (Navajo) has created glass panels, which incorporate woven designs such as those made by her grandmother. These works reflect the importance of textile production in Native life.

Gifts from the Sea

Native Americans have traditionally regarded all of nature as an integrated whole, and nature often plays an important role in tribal ceremonies and art. Legends and stories often involve animals of the land, sky, rivers, and oceans.

A major section of the exhibit is devoted to the sea creatures that are so important to the tribal peoples of the Northwest coast. Tlingit artist Raven Skyriver has created beautiful sea animals using an off-hand sculpture technique, and both the quality of the sculpture and the colors he creates are visually striking.

There are several renditions in the exhibit of orcas, which are the largest member of the dolphin family. Orcas are important in Native life and legends and are frequently depicted in the art of Northwest Coast tribes. The orca is said to protect those who travel away from home, and to help lead them back. Orcas in the exhibit have been created by several artists, including Skyriver, Singletary, and Marvin Oliver (Quinault/Isleta Pueblo).

Water is often incorporated into art to express concern for the environment, especially the rising oceans. Rivers have played a significant role in the siting of settlements for tribes, and Brian Barber, a Pawnee architect and glass artist, has created a site model in glass of the area of the Platte River adjacent to a Pawnee sacred site on the American plains. There also are a number of pieces in the exhibit that represent the tools for trapping and catching fish for sustenance, historically an important part of tribal life.

Animals of the Land

Respect for the animal world is a prominent cultural principle in Native communities. When animals are killed for food, the hunter thanks the animal and explains how its body will be used. Animals may also provide spiritual guidance. Bears symbolize strength and courage, and wolves figure predominantly in legends where they generally signify protection. Numerous depictions of these and other totemic animals are included in the exhibit by such well known artists as Ed Archie NoiseCat (Salish/Shuswap), Ira Lujan (Taos Pueblo/Okhay Owingeh), and Dan Friday.

Friday’s great-grandfathers were well known wood carvers, renowned for totem pole carving, as well as for being culture-bearers in their community. Creating totem poles in glass became for Friday a way of continuing his family’s traditions. The exhibit also includes the first known creature created in glass by a Native artist: Scorpion (ca. 1978) by Larry Ahvakana (Inupiaq), who was the first Native artist to work in glass, beginning at the Rhode Island School of Design in the early 1970s.

Courtesy the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture.

The Sky Above and Flying Creatures

Long before European contact, Indigenous tribes of the Americas had advanced knowledge of astronomical cycles, and depictions of the sun and stars were common. Made by many tribes, star maps reflected the heavens and also a philosophy of being. Weather-related aspects also appear in drawings, such as depictions of clouds and lightning and other symbols of thunder and rain. Artists have reimagined such elements in blown and cast glass.

Ancestral Puebloan peoples incorporated this information about the sun and moon and the alignment of sunrises and sunsets during solstices and equinoxes into their architecture, as found at the ruins of Chaco Canyon in New Mexico. Works in the exhibit of several artists reflect this knowledge of the heavens, including pieces by well-known sculptor and glass artist Adrian Wall (Jemez Pueblo).

Birds and other flying creatures play primary roles in many Native myths and other stories. Eagles carry prayers to the Creator. Owls and other birds are featured in totems. Other flying creatures in the exhibit include Butterflies by Ramson Lomatewama (Hopi), Carol Lujan’s (Navajo) Dancing Dragonflies, Ira Lujan’s (Taos/Ohkay Owingeh) Quail Canopic Jar, and Circling Ravens by Shawn Peterson (Puyallup). Several artists have also depicted creatures as decorations on vessels or baskets, combining the making of utilitarian objects with their respect for birds and other animals. The resulting works are notable for their artistry as well as for their cultural expression.

Courtesy the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture.

A major focus of Singletary’s work is the Tlingit creation story of Raven stealing the sun, the moon, and the stars and flinging them into the sky to give light to the people. Singletary has become internationally recognized for the brilliant combination of his talent for creating glass objects and his use of the forms and symbology of his native Tlingit culture.

Interpreting Ancestors’ Voices in Glass

Native glass artists have also drawn inspiration from their tribal mythology and oral histories, reinterpreting traditional stories or designs in glass. Communications from the ancestors in the form of petroglyphs and pictographs also link current Native communities to the past. Glass artists have symbolized their ancestors through cast glass masks and other regalia, and through cast or blown glass version of ancient pictographs. These works in glass are an interpretation of cultural heritage and serve as ways of honoring and giving voice to ancestors.

Lillian Pitt (Wasco/Yakama/Warm Springs) developed her own approach to art by studying the petroglyphs and pictographs of her ancestors, who lived in the Columbia River region of the Pacific Northwest for more than 10,000 years. She Who Watches, a lead crystal mask she made from a mold, is her depiction of a famous rock art image that is both a petroglyph and a pictograph. The ancient rock art, perched high on a mountain, is visible from her ancestral village, and it is dominant in the stories and oral history of her people. Ancestors’ Messages, which is from a recent Pitt collaboration with Dan Friday, is a blown-glass piece in the shape of a Wasco-style sally bag—a type of cylindrical root basket—with petroglyph figures of people and birds fused on the surface.

Ramson Lomatewama is a member of the Eagle Clan of the Hopi Tribe, known for his blown and hand-sculpted glass spirit figures and corn maidens, which are drawn from his study of Hopi artifacts and iconography. His compelling spirit figures in glass are inspired by photographs of rock art in Horseshoe Canyon in Canyonlands National Park in Utah. Some of the most significant rock art in North America, these ancient works date to the Late Archaic period, from 2000 BCE to 500 CE. Lomatewama has developed a sense of how Hopi perspectives influence his creations. In a glass vase, terracing at the rim may be a representation of the Grand Canyon, while glass bamboo may represent the Hopi creation story of emergence from the Third World; and a traditional corn maiden recreated in glass may represent prayers or gratitude for a bountiful corn crop.

Another way that Native cultures convey ancestral knowledge is through ceremonies and ceremonial regalia, such as an arresting Ghost Shirt by Chippewa artist Rory Erler Wakemup.

Nuu-chah-nulth artist Joe David collaborated with Singletary on Looks to the Sky, a three-dimensional bust that resembles masks carved in wood by David. Recognizable as Nuu-chah-nulth in the design of the features, the head is set on a torso that could be from any one of numerous cultures, Native and non-Native, which creates an interesting juxtaposition.

A Singletary collaboration with Marcus Amerman (Choctaw) resulted in a series of large blown-glass portrait jars entitled Voices from the Temple Mound, which are reminiscent of ceramic portrait jars of the Mississippian culture of southern and midwestern North America, which flourished from 4500 BCE to 1600 CE. Several of these glass jars representing the ancestors are presented in the exhibit.

Bridging Two Worlds

A number of important works in the Contemporary Native Arts movement have focused on the dichotomies of living in two worlds, balancing those things that honor traditional cultures and those things that conform to the mores of mainstream society. Joe Feddersen has created an installation for the exhibit of hanging glass charms, which represent a cultural continuum from ancient petroglyphs to pop culture iconography, thus bridging two worlds. The charms create both a dialogue between past and present and an echo between the glass charms and their shadows. Each charm is made of cut and fused glass pieces. Feddersen has also created works which reflect on the differences in past and current tracks on the landscape.

Pueblo potter and fashion designer Virgil Ortiz (Cochiti Pueblo) also has created works in glass, and he has created characters in glass to tell a science fiction story related to efforts in the distant future to save cultural artifacts destroyed in the Colonial period by Spanish invaders, thus bridging past, present and future.

Angela Babby (Lakota) has developed a unique technique for creating glass on glass works using powdered enamel which she liquifies and then paints on glass. Whether picturing two-spirit individuals in front of the Supreme Court with the inscription “Equal Justice Under the Law,” or juxtaposing a traditionally clothed Inuit child with a changing climate, Babby’s works often draw from history and are expressions of issues affecting Native peoples and/or society at large. Her works also provide pointed social commentary.

Conclusion

Native glass artists are part of a continuum of generations that have created art that reflects cultural knowledge and traditional designs, and their inspiration often stems from tribal lifeways. These artists have incorporated their traditions into artistic expression across an ever-evolving set of media. While glass is not a traditional medium for Native artists, a growing number have been attracted to glass, both for the properties inherent in working with glass and the joy of working in collaboration with a community of glass artists. Although glass is a relatively new medium for the creation of Indigenous art, cultural heritage remains integral to the practice. The Native artists working today in glass have, to a significant degree, taken on the role of culture-bearers as they lead in the development of this relatively new form of indigenous art.

The artists featured in Clearly Indigenous are all established artists; some have had long careers as glass artists, while others have only recently turned their artistic endeavors to the medium. These artists have melded the properties inherent in glass art with their cultural knowledge to create a remarkable body of work that reflects both traditional heritage and contemporary aesthetics. The result is a stunning presentation of thought-provoking and beautiful works of art.

—

After a distinguished career in federal and state government, as a business CEO, and as the Heard Museum CEO, Dr. Letitia Chambers returned to Santa Fe in 2012, where she has lived off and on for 50 years. She has curated major exhibits for MIAC and the Santa Fe Botanical Garden and is the author of Clearly Indigenous: Native Visions Reimagined in Glass.