Not So Niche

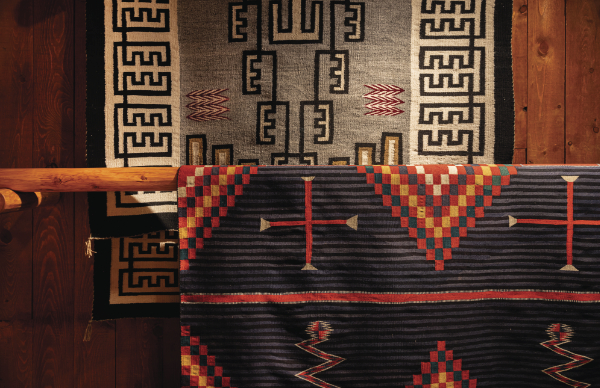

Foreground: Unknown artist (Navajo), Hubbell Trading Post rug, ca. 1800-1890. Commercial Germantown wool. 81 7 8 × 62 inches. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Edward H. Tatum.

MIAC Collection: 36197/12. Background: Unknown artist (Navajo), Two Grey Hills rug, ca. 1910-1920. Handspun wool, aniline dye. 88 3 5 × 54 ¾ inches.

Gift of the Santa Fe Opera. MIAC Collection: 56595/12.

Foreground: Unknown artist (Navajo), Hubbell Trading Post rug, ca. 1800-1890. Commercial Germantown wool. 81 7 8 × 62 inches. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Edward H. Tatum.

MIAC Collection: 36197/12. Background: Unknown artist (Navajo), Two Grey Hills rug, ca. 1910-1920. Handspun wool, aniline dye. 88 3 5 × 54 ¾ inches.

Gift of the Santa Fe Opera. MIAC Collection: 56595/12.

By Charlotte Jusinski

In a recent email to a colleague, I found myself describing El Palacio as a “niche” magazine. But even as I wrote it, I knew it didn’t feel right.

Looking at it in a more pigeonholed point of view, I guess it could be considered specialty. El Pal is specifically tied to the programming of the museums and historic sites of New Mexico, and more loosely focuses on the art, history, and culture of the Southwest as a whole. It’s primarily read by people who love New Mexico, whether they live here or travel here (or want to live here or travel here). That seems a bit specific.

But I’d argue that El Pal is anything but narrow. New Mexico’s remarkable system of state cultural institutions is incredibly diverse in its scope and range of emotion and experience. Whether you’re looking for art made by humans who lived in New Mexico a millennia ago, wondering what the future will hold as New Mexico continues to push forward space exploration, want to dive into what brought Easterners here in the early nineteenth century, or are just looking to enjoy the quiet company of a cow, there’s a state museum or historic site for you. And El Palacio brings them all directly to your mailbox.

Even in this issue alone features a wide range of subjects that would probably interest just about anyone. James Snead’s archival deep-dive into a story of sexual harassment in the world of anthropology should be of great interest to at least half the world’s population (and ideally all of it) as it explores the obstacles set before aspiring female anthropologists in the early 1900s—though many of the exchanges chronicled therein probably could be set right here in the early 2000s, too.

Two features about exhibitions at the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture (Here, Now and Always and Grounded in Clay) zero in on the need for community and authenticity, especially as Indigenous people contend with the manipulative legacy of many museum institutions. It’s a shift in curation that affects the way we view and visit museums—and thus should affect our thinking about the way the history of our state and our civilization is told and retold. That’s pretty wide-reaching, no?

Pivot your view of Santa Fe with an excerpt of Dana Tai Soon Burgess’s new memoir, Chino and the Dance of the Butterfly, where we see the Santa Fe of the 1970s through the eyes of a child. Burgess’s vivid account of his childhood in Santa Fe allows us inside the head of an artist in the making: Burgess is now a world-renowned choreographer who attributes much of his creative childhood to his formative experiences here. It’s a feeling many have felt in Santa Fe and beyond, and explores a creative mind from the inside.

Transgressions and Amplifications, an exhibition at the Museum of Art explored by Emily Withnall, seems very specific at first: genre-bending photography from the 1960s and ‘70s. But scratch the surface a little bit and you’ll see that much of what led these artists to create such subversive works were emotions and experiences held by just about anyone.

A review of Old Santa Fe Today by Paul Weideman and a brief look at a collaboration between Coronado Historic Site and Los Alamos National Labs by Hannah Sherk round out an issue as diverse and varied as the people who read it every quarter.

So maybe at first El Pal might only appeal to adherents to the gospel of New Mexico museums, but I urge you to think about the big picture. The stories herein can be endlessly extrapolated to apply to anyone, anywhere, doing anything—not so niche, in the end.

—