On the Ball

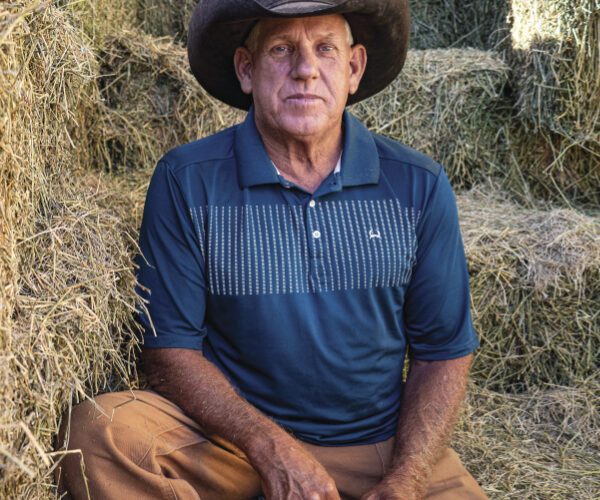

Meet the New Mexico Farm & Ranch Heritage Museum’s renowned livestock program’s singular figurehead

By Amy Smith Muise

Photographs by Gabriela Campos

I met Greg Ball on a fine, hot morning in August, on a weekday when the museum wasn’t crowded. He’s been the livestock manager at the New Mexico Farm & Ranch Heritage Museum for twenty-four years now. Our conversation started about rain, as is often the case in the desert Southwest.

Along with his full-time job at the museum, he has a small farm in Mesilla, and as of early August it hadn’t rained much there.

“It’s rained here a lot, but this is a gravel pit.”

I had to laugh. We stood in front of a lofty horse barn among manicured lawns, paths, and clean, well-maintained livestock pens. “Gravel pit” isn’t the first descriptor to come to mind.

“When I came here, where that bathroom is, there was a 50-foot hole there,” he says. “There was an arroyo about where we’re standing. We kind of channeled the water, here and there. So it’s been quite interesting, to put it all together over the years. These cattle… I’ve raised them. Third and fourth generation on some of them. They’re kind of my babies.”

Greg is the type of person who can seem real tough and real sweet at the same time. Perfect for a public-facing job like this.

As we talk, a trio of Swainson’s hawks are calling from their perches on the fence and roof, surprisingly close to us. I ask what they’re after. “A rabbit or a quail or something,” Greg says, “it just has to make the wrong move.”

I ask if they are always so vocal.

He makes a loud, hoarse whistle just like the hawks’. They call back. “Yeah, you can sit here and talk with them,” he says.

The New Mexico Farm & Ranch Heritage Museum encompasses 47 acres in Las Cruces, on Dripping Springs Road across from Tortugas Mountain (and yes, it sits on sand and gravel deposits of the ancestral Rio Grande). The museum arose from long grassroots interest—it was the vision of William P. Stephens, former director of the New Mexico Department of Agriculture, and Gerald Thomas, then president of New Mexico State University, as well as from efforts of the Office of Cultural Affairs (now the Department of Cultural Affairs) and the New Mexico Department of Agriculture. It opened to the public in 1998, around the same time a rancher on the museum’s board, John Yarbrough, contacted Greg and asked if he’d be interested in starting up a livestock program.

“They just wanted something simple,” says Greg, “and it started simple, but it’s turned into this monster that it is now!” He laughs. “I just call it that. It’s just turned into a lot of work.”

He speaks highly of the crew who helps him with that work. “People think they want to be in the livestock business or want to be a cowboy, but a lot of them figure out they don’t. Or I’ve had some really good crews, nothing but good cowboys, but they don’t want to talk to people; they want to be on a horse. And they’re great help and they do things well in front of people, but they don’t want to talk.”

That’s not the case with the current crew: Ross Zuniga and Jake Montoya. “They’re good. They’ll talk. Real kind-hearted. That shows up. Cattle really pick up on that.”

The museum is set on two sides of Tortugas Arroyo. These days, to get from the main museum building to the livestock area, visitors cross it on a regal green bridge that once served as part of a three-span across the Pecos River near Roswell, and later was moved to the Rio Hondo. It was installed in its present location in 2007.

Greg points out a white barn near the arroyo. “This was the first building. … The dairy barn. Southwest Dairy Farmers. That sidewalk, that was the only way to get across. [Dairy] was really the only thing to do… and then we slowly started building other things, and we started down there. Once we started, Smith & Aguirre Construction Company, they came in here and did all the dirt work for us. They came in, put in all the utilities… found all the elevations, put water to drain. There was always a lot of ideas of what was going to go down here. I can remember some of them saying: ‘That cowboy’s going to build a fence, fence off everything down here.’ So I did.’”

“Did you do all this welding yourself?” I ask. There’s a lot of pipe fence and welded wire.

“Uh-huh.”

Greg tells me he’s been lucky over the years to have directors who gave him the freedom to develop things his way on this side; and the current director, Heather Reed, who took on the position in November 2020, is no exception. You can tell Greg has had a long-term vision. The livestock area has the kind of harmony of shape—geometric, but following the lay of the land—that says its maker has pondered every aspect of the site.

“Almost everything here, we built,” Greg says, pointing out a few exceptions. A lot of the work has been on the setup of livestock pens that he’s rightly proud of. As a farm girl, I admire the sheep pens right away: grassy paddocks laid out with pipe frames and sturdy mesh panels. Sheep excel at escape. Greg explains that his team built those during Covid lockdowns when most of the museum was closed, but of course, the livestock department wasn’t.

We walk around the sheep and goat barn, a pleasant, airy building with indoor-outdoor runs for the animals and beautiful hand-painted signs describing modern and historical breeds of sheep and goats in New Mexico. In the center of the barn sits a sheepherder’s wagon, a moveable dwelling used throughout the American West as lodging for those who traveled with the flocks. Peering through the glass, I see a narrow bed with threadbare quilt, a washbasin, a small wood stove. It’s hard to imagine that life.

The devotion of caretakers of livestock on the range and in the mountains is kin to the devotion that all livestock managers feel. Animals require daily care, feed, water, a careful eye on their health. Greg says it was peaceful during Covid, when only he and the crew were around.

“We just did a lot of things when everybody was gone,” he says. “Put all the stays in that fence. We have barriers now, between everything, for the safety of the public.” Also for the safety of the animals. “People will feed them whatever,” he admits.

Despite this barricade, Greg has had pretty good experiences with museum visitors. “It’s been a very fun place,” he says. “And to tell you the truth, whatever black eye agriculture has”—I think he means the public’s concerns about animal welfare and environmental impact—“I haven’t seen it. Even though… my wife says I’m kind of an unapproachable guy. I have an unapproachable personality.”

I find this hilarious. He’s pretty charming.

Greg likes to do his livestock work openly, where visitors can observe the daily goings-on. A highlight during organized events is the Parade of Breeds, where the crew bring cattle through for viewing, in order of their historical introduction to New Mexico. Greg will talk to the audience about each breed, its carcass characteristics, and what type of environment they do well in. “Not all these breeds belong here in the desert Southwest,” he emphasizes. In the early 1990s, he worked as a research assistant at New Mexico State University under Dr. Bobby Rankin, studying crossbred commercial cows for desert environments. This work familiarized him with many beef breeds and crosses, including Simmental, Charolais, and Hereford crosses, and purebred Brangus. His favorite mama cows, he says, are a Brangus-Hereford cross.

“I’m extremely fond of them.”

Although the livestock program keeps and uses bulls onsite, Greg sometimes artificially inseminates cows to bring in genetics from elsewhere. He tells the story of one of the few times he stopped what he was doing to warn visitors away.

“Some ladies and some little girls,” he says, stopped by to watch while he was AI-ing some cows. “You’d better go… look around,” he told them.

“Oh, no,” they said, “It’s okay. We watch Doctor Pol [a TV veterinarian].”

“Who’s Doctor Pol?” Greg asked.

“You don’t watch Dr. Pol?” they said.

“No.”

Greg has a way of finishing up anecdotes by quoting his own laconic responses.

“So the public does get to watch you work cattle?” I ask.

“Yes, we don’t hide anything from them.”

He also encourages visitors to watch the crew working with young horses. At the far end of the horse barn is a beautiful round pen with bleachers where observers can sit up and get a good view of what’s happening.

Greg has been starting colts for most of his life, as well as training head and heel horses, cutting horses, and working ranch horses, especially for pen work. “Sorting horses,” he specifies, referencing horses trained to divide up groups of cattle, “that’s kind of my niche. You have to pay attention to what you’re doing. Can’t sit there yacking on your phone. Or something tries to go by, and…” He makes the universal gesture for getting dumped when your horse dives out from under you to turn a cow.

“It’s been fun here because I’ve gotten to do it as a demonstration,” he says. Whatever he needs to do on a given day, with a given horse, that’s what he works on, and the public can watch and learn. He doesn’t like to be videotaped, though. “This day and age, everyone just comes in and thinks they [should] videotape you.”

I make a mental note to take it easy with my camera phone. For those who take pride in their “feel,” handling horses and cattle with sensitivity, a random capture can unfairly preserve an inelegant moment. “I’ve been in the cattle business for forty-two years,” Greg says. “I grew up around old cowboys, so… handling cattle—it always cracks me up—‘quietly’ is nothing new,” he says; referencing low-stress ways of working cattle. “Because… it was really frowned upon [not to]. Everything was done on a horse.”

Cattle tend to feel comfortable around horses, as fellow prey animals. They respect them, but don’t fear them. When humans get horseback, cattle can see us more easily and don’t get as nervous as when we mess around at ground level.

“It was almost sacrilege to work cattle in a pen on foot. The old-timers just wouldn’t do it. That’s how I got involved in horse training.”

Greg gestures to the corrals that spiral back to the edge of the property. “These pens are for a guy that wants to do things on a horse. … Long ways. Big. All the latches are up on top.” He designed these gate latches, easy to open and close from horseback; they don’t require getting down, opening a waist-level latch, leading a horse through, then closing the gate on foot. It can all be done from the saddle.

This way, the crew can bring cattle from any direction to the sorting chutes next to the barn, all while staying horseback. The corrals fit together in a long connecting path. There’s no stress or difficulty in maneuvering through gates or alleys. Everything just sort of flows…

“…most days,” says Greg.

He doesn’t want me thinking all museum visitors are angels. So he tells his story about the one time—just once—some guys tried chucking rocks at a bull.

“And these were older men! They said, ‘He started it’—meaning the bull. I said, ‘You’re kidding?!’ I told them, ‘I got third graders [touring the museum] more mature than you guys.’ Boy that made them mad. But in all the twenty-something years, that’s all. One other lady, she came up and said, ‘One of those pens doesn’t have any water in it.’ And you can see right here, the troughs split the pens. There’s water in both pens. And I had one old cowboy working here then, he said I should have told her, ‘That’s a breed that we’re raising that doesn’t need water here in the desert Southwest.’”

I get the impression they have a pretty enjoyable sense of humor around here.

Greg says he’s lucky to have started the livestock program and to have stayed here to see it grow. As a young man, he worked on ranches for the Yateses (of Yates Petroleum). When he moved to Mesilla he wasn’t really planning on staying there, but “life gets in the way.” He met his wife here, and they’ve been married for thirty-two years. Their sons are both athletes who played Division 1 college ball (one football, one baseball). Greg also has a daughter who works at a veterinary clinic, and I can tell he’s pretty proud of her skills and toughness.

It’s time for the tour of the cattle, so we climb aboard the UTV to make the rounds. The livestock program produces registered bulls, as well as heifers, and sells them as part of its process. I see some nice young bulls, Angus and Hereford, that will be ready by the fall. They also raise Brangus bulls, most of which have already been sold for this year. “You want them all the same size,” says Greg, “want them all to look the same, all look good. That way you’ll sell them all.” He shows me some older cows that raise “the best heifers” every year, and one who regularly has twins. “We try to explain everything that we do. And I think people don’t realize how much we know about them… as far as the genetics of them, their personalities.”

To show me a bit of that personality, Greg gets out of the UTV and climbs over a tall fence with extraordinary nimbleness. (He casually mentions he’s had five back surgeries.) A massive bull sidles over for scratches, clearly used to socializing. All the cattle on the place are gentle—testament to the calm, daily attention Greg and his crew pay them, and to their lack of stress in handling.

Their working chutes accommodate many different kinds and sizes of cattle, including special facilities for longhorns (staggered openings allow them to move their horns through the chute one at a time) and a hydraulic squeeze chute for doctoring or other delicate work.

“This is the hoof-trimming chute,” he tells me, “but we don’t really need it.”

I joke (am I getting the hang of this?): “Because you’re in a gravel pit!”

Greg works his cattle slowly through the alleys, not filling them up, just six or seven at a time. “Just gets rid of all your mess, all your problems,” he says, “especially if you do it horseback. … I mean, we could pack them in here… but sooner or later, something goes wrong.”

The radio in the barn is playing a cover of Hank Williams’s “Honky Tonkin’.”

We tour pens of Angus, Hereford, and Brangus cattle, as well as some beautiful longhorn cows and a Brahman bull. Greg shows me the facility’s roping arena and the Corriente steers they raise for the recreational cattle market (cattle used for roping practice and competition). He says that demand is good right now. Staying home during Covid lockdowns brought people back into team roping.

At this edge of the property there’s an almost-2-acre field remediated with fertile soil from the Mesilla Valley. Here, the crew grows giant Bermuda grass to pasture cattle for grazing when they can. The rest of their forage is stored nearby, in enormous haystacks of small bales under sheds. Across the fence we can see Centennial High School. Greg has explained that before the high school was built, they used to have a water feature nearby, with wetland plants. Fearing it might be too much of an “attractive nuisance” so visible from the high school, he decided to fill it in, moving several cottonwood trees to new locations in livestock pens. They provide much-needed shade in the hot climate of Southern New Mexico. “We have other shades, the shade structure and the walls,” Greg explains, “but nothing makes better shade for cattle than trees.”

As it nears midday, we can see cows, calves, and bulls clustered beneath them.

I ask about the roping arena, and he explains they hope to use it more once they level some land for parking (for pickups and horse trailers). As for Greg, he can’t really rope anymore after his back surgeries. “Hasn’t really stopped me from riding,” he says, “but it’s stopped my roping.” A battery sewn under his skin with two wires run into his vertebrae helps him walk and tricks his brain to ignore pain from a spinal cord injury. It’s been an improvement in life, he says. He controls the device from what he calls a “little bitty iPad.”

Greg’s vision for the livestock program still feels alive and electric, after all these years, as he talks about the lineages of cows and bulls, the long arc of his breeding programs for Angus and Hereford, Brangus and Corriente. Meanwhile, Greg tells me about the alley we’re traveling down: “I’m going to rebuild all this. And put some swinging gates in there.” He muses, “One of these days I’ll retire. And one of the things I did to get myself to my retirement was I built myself a new round pen in the back of my roping arena [in Mesilla]. My wife said, ‘What are you going to do with that?’ and I said, ‘I’m going to break colts.’ She says, ‘Wasn’t that what you were doing twenty-five years ago?’ I said, ‘Yeah! I’m going to retire and get right back to it.’”

—

Amy Smith Muise lives on a cow-calf ranch in Otero County and works in the Department of Innovative Media, Research & Extension at New Mexico State University. She grew up on a sheep farm in Manitoba, Canada.

Gabriela Campos is a photojournalist based in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Her work has been featured in The Guardian, High Country News, Al Jazeera, VICE, and numerous southwestern publications. She is currently on staff with the Santa Fe New Mexican.