Everything New is New Again

One hundred years of genius

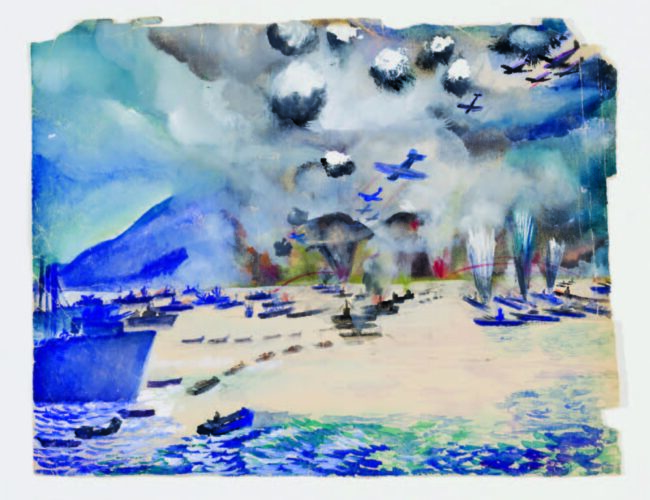

Lloyd Kiva New, Battle of Iwo Jima from the Deck of the USS Sanborn, 1945. Watercolor on paper. Photograph by Jason Ordaz. Courtesy of Aysen New. Helen Miller Jones, 1986 (1986.137.14).

Lloyd Kiva New, Battle of Iwo Jima from the Deck of the USS Sanborn, 1945. Watercolor on paper. Photograph by Jason Ordaz. Courtesy of Aysen New. Helen Miller Jones, 1986 (1986.137.14).

BY CINDRA KLINE

LLOYD HENRI KIVA NEW’s life as designer, artist, scholar, and visionary educator remains a call to creative souls still listening to what New frequently referred to as “the sound of drums.” In celebration of his influence, and honoring what would have been his 100th birthday, a collaborative effort between three Santa Fe museums spotlights the man and the motivation he has provided to so many individuals.

New was an only-in-America blend of Cherokee and Scots-Irish heritage, raised by a father most would refer to as Mormon but whom Lloyd called a member of the “Reorganized Church of Latter Day Saints.” Lloyd’s experiences throughout the United States at a young age molded him into the icon now so admired. Born on February 18, 1916, during a dry Oklahoma winter, he spent the majority of his youth in Jenks, a suburb of Tulsa. Driven to question and create, he initially attended Oklahoma State University, at the time Oklahoma A&M, but disliked the deluge of math and science courses. New embarked for fresh horizons. With a collective fifteen dollars in their pockets, he and a group of friends hopped a train to Chicago to see the 1933 World’s Fair. While there, New also visited the Field Museum collections and the Museum of the Art Institute of Chicago. Impressed by what he experienced, he later enrolled as a student at the Art Institute, awakening his innermost calling—to explore, expand, and advance Native art and what he envisioned as its infinite possibilities.

“The Pre-Columbian collection at the Art Institute of Chicago reaffirmed what New often referred to as his ‘sound of drums,’” explained Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA) archivist Ryan S. Flahive, the editor of New’s memoirs, The Sound of Drums: A Memoir of Lloyd Kiva New (Sunstone Press, 2016). “Even during the early years of his career, New recognized a sense of stagnation in Native art production and was determined to ‘move it to the next level’ with the help of others.”

“Indian arts” was a term traditionally and loosely applied to craft items, textiles, and recognized jewelry styles (squash blossom necklaces, for example) and a rather defined set of parameters. American buyers of the early 1900s embraced what was perceived as “authentic” Native American design, beginning in earnest during the heyday of the Craftsman/Mission style, boosted by Gustav Stickley before 1920. Women’s publications of the day favored the post-Victorian, less ornate look, and magazines such as Ladies’ Home Journal encouraged Anglo women to decorate portions of their homes as “Indian corners,” a craze that helped to promote appreciation of Native arts but also, so to speak, put Indians “in a corner” creatively.

Rounding the Corner

New envisioned a creatively nurturing environment for Native artists of all cultures and fields of interest that would allow an alternative to what had been traditionally offered by Dorothy Dunn (the art instructor who created The Studio School at the Santa Fe Indian School) and others. He wanted to explore fabrics and dimensional art with an eye to modernity. Dunn is highly regarded for her artistic visions, but New wished to go further. Dunn encouraged a refined, European approach. Her students tended to churn out gorgeous but flattened paintings reflecting stoic renditions of Native life, which perpetuated the then-recognized portrayal of Indians.

“Trans-customary art crosses boundaries between traditional and nontraditional art forms,” explained Carmen Vendelin, curator at the New Mexico Museum of Art. “Art forms based on traditional models created for nonindigenous buyers and the paintings by Santa Fe Indian art school artists are, to a degree, trans-customary in that they are not objects used traditionally by the respective tribes. Therefore, the emotional and intellectual engagement for Native students alongside contemporary art practices and styles encouraged at IAIA was far more radical.”

New’s fateful train trip to the World’s Fair sold him on the Windy City, and he graduated from the Art Institute of Chicago in 1938 with a degree in art education, not fine art—notable because education, not “art” in and of itself, would be his career focus. Launching his teaching career during the challenging years of World War II, he enlisted in the Seabees in 1941 to serve in the United States Navy and became the “ship artist” for the USS Sanborn in the Aleutian Islands. New rendered vibrant watercolors, including prebattle images of Iwo Jima from the deck of the Sanborn.

Decades later, in 1984, as president emeritus of IAIA, New wrote a paper detailing IAIA’s role in the development of modern Indian art. Quoting Edmund Carpenter, he stated: “To experience the unfamiliar in tribal art, we must step outside the patterns of perception of our culture and explore new worlds of images, new realities. . . . Anything less merely confirms previous convictions.” New added to Carpenter’s observations: “To the extent that art is usually a reliable barometer of social movement and harbinger of change we should look carefully at the expressions of the Indian painter, sculptor, writer for insight to the present, and perhaps, as a glimpse of the future.”

Such words are as relevant today as when New wrote them. And New’s artwork as a recent graduate of the Art Institute of Chicago and from his time serving in the navy offers glimpses into the worlds he was exploring. Decades later, at the age of eighty-five, New received an honorary doctorate from the Art Institute of Chicago, yet, according to Flahive, “he rarely exhibited or sold his work as a professional artist, although he was a skilled painter.”

A New Way of Thinking

A mere two years after New embarked on his teaching career, the Second World War interrupted his creative aspirations. Before departing to defend his country, he recruited Fred Kabotie (Hopi) to assist him with a mural for San Francisco’s Golden Gate International Exposition, held in 1939 –40. It was Kabotie who suggested another young Hopi artist, Charles Loloma, for the project. New was twenty-two, and Loloma only seventeen; they’d first met when New was teaching at the Phoenix Indian School. New recognized Loloma’s inherent brilliance, and they formed a lasting friendship.

It is said that luck is nothing more than preparation meeting opportunity, but Native American jewelry is forever blessed because New and Loloma came together, blending talents and inspiration. Their collaboration forever transformed the definition of “Indian art.” Combining creative forces so early in their careers, each profoundly influenced the other.

New went on to pursue a successful career as a fashion designer in Scottsdale and internationally during the 1940s and 1950s. Loloma became a defining force in both the concept of personal adornment and jewelry-crafting techniques, and taught at IAIA, supporting New’s enthusiastic visions for Native youth. They worked together from 1957 through 1961 on a Rockefeller Foundation project.

New left the navy as a full lieutenant in 1945 with an honorable discharge. Returning stateside with a new state of mind, he opened a studio in Scottsdale, Arizona, in 1946, perfecting never before-seen mix-ups of clothing collections that incorporated his Cherokee heritage with Anglo preferences. His inspired designs were noticed by upscale clients, including Neiman Marcus, and, realizing the value of his Native American heritage, New sought a catchy trademark to cinch his growing national recognition.

The 1950s were transformative for both Scottsdale and the artists who sought out the area’s inspiring atmosphere. John Bonnell, owner of the renowned White Hogan, relocated his shop from Flagstaff to Scottsdale. The White Hogan produced unique silver items, including silver serving pieces and flatware, utilizing the skills of now-famed silversmiths Kenneth Begay and Allan and George Kee. Clothing, jewelry, exploring the limits of style and personal expression through the interpretation of Native American eyes and hands—it was an exciting time, and New knew it was time to make the most of his newfound niche.

Eventually New abandoned his career in fashion design to devote his attention to education through the Southwest Indian Arts and Crafts Workshop—a conference hosted by the University of Arizona that explored the results of connecting Native American youth with contemporary art and planted the seed for IAIA after the “experiment” met with outstanding success. He also spent two years as a teacher at the Phoenix Indian School, a boarding school with a mix of Native American students, which cemented in him a desire to pass along his personal passion and inspire others’ drive and talents.

Branding (Not Horses)

New seemed destined for the world of higher learning, perhaps not only to inspire and help aspiring artists but also because he valued the formal schooling and access to the world that he’d enjoyed. From a young age, he felt strongly about pushing the boundaries of what indigenous art could, or should, be. He blurred the cultural lines with his upscale clothing and purses incorporating Native motifs. Scottsdale housewives and, soon, he trendiest women across the country began snatching up his high-concept designs, and New skyrocketed to prominence, first in Arizona fashion shows, then in New York and beyond.

Sometimes it is the simplest notions that spark change. New envisioned leather accessories adorned with concha clasps and fabrics in a wide range of vibrant motifs—an affordable, aesthetically interesting meld of Anglo preferences and Native American design skills and sensibilities, in many instances introducing them to naïve audiences. Well-heeled women of the era may never have dared to pair pearls with lipstick and turquoise-laden concha belts, yet it was deemed trendy to display individual brass or silver, hand-stamped conchas on purses once New presented the notion. And it exploded from there, catapulting his style and Scottsdale studio to dizzying heights. Recognizing that his success could pave the way for unbridled opportunities in the perception of tribal arts, New continued to strive for cutting-edge appeal; Ralph Lauren likely pays daily homage.

As a young man, then aspiring silversmith and jewelry artist Charles Loloma provided many of the metal concha pieces that adorned New’s leatherwork, which was prominently featured in his advertising and displayed in bigcity department store windows. The concept of branding is not new to us today, but New was ahead of his time in recognizing the value of memorable market positioning. In 1946 he consulted with a savvy business associate, silent-movie actor Bert Grassby, to better highlight his heritage and come up with a catchy way to brand himself; hence the “Kiva” moniker incorporated into his identity. (Kivas are not part of Cherokee religious practices but are prominent in Southwestern Pueblo culture, and given New’s focus on life in Arizona and New Mexico, it is not surprising that he embraced the addition to his legal name.)

“It’s interesting,” commented Flahive. “Throughout his career, he signed his name very inconsistently. On the war paintings, it includes ‘Henri,’ but later paintings and writings were signed ‘Lloyd Kiva,’ or ‘Lloyd H. New,’ or just ‘Lloyd New.’” Perhaps lack of attachment to his name was what initially drove New to add his new moniker, “Kiva.”

When the Land of Enchantment called his name(s), New left Arizona and made his way to Santa Fe. In 1961, as he wrapped up his Rockefeller endeavor with Loloma, he accepted an invitation from the Bureau of Indian Affairs to establish a school with Dr. George Boyce. Eager to implement New’s educational visions, the BIA had surprisingly open ears, and therefore New is often recognized as the “creator” of IAIA, although his initial role was to serve as art director alongside Boyce. Understanding that talent and ambition must first be recognized to be nurtured, New eagerly embarked on the academic path that would map out the remainder of his years.

New Century, New Appreciation

Originally conceived as a four-year high school program with an emphasis on fine-art training and an additional two-year postgraduate program, IAIA evolved into the highly respected institution it is today, renowned for its innovative, multi-tribal approach to creative learning.

Dr. Dave Warren (Santa Clara), a former IAIA faculty member, wrote in New’s obituary, “The creative genius behind what he did is not only in serving Native American artists, but finding a way to look at the meaning of art and culture and put them into an institution and a philosophy” (New York Times, February 10, 2002).

More than a decade after New’s passing, the adage “Everything old is new again” takes on new meaning: contemporary Native art and fashion are hotter than ever. Stroll down Santa Fe’s Canyon Road and see how many vintage and antique galleries have been replaced with ones dealing in modern Native art.

The availability of New’s twentieth-century archives at IAIA offers students and scholars an untapped resource for twenty-first-century inspiration. New’s widow, Aysen New, donated fifty-plus boxes containing more than fifty cubic feet of ephemera, everything from meeting minutes to manuscripts. The collection includes New’s audio and visual materials, sketches, and photographs, and provides insight into his rise to fame as a Scottsdale textile artist throughout the 1950s as well as his lifelong commitment to bettering opportunities for Native American artists of all genres. Twenty-six folders contain correspondence spanning from 1938 to 1997, including one folder pertaining to Lloyd Kiva New’s years in the military. The personal papers reveal his camaraderie with political dynamos of the day, including former New Mexico governor Bill Richardson and Supreme Court justice Sandra Day O’Connor.

Lloyd Kiva New died in 2002, two years after he received his honorary doctorate from the Art Institute of Chicago, and within a week of his eighty seventh birthday. That year also marked IAIA’s fortieth anniversary as his academic institution. Join in Santa Fe’s celebration of the man and his visions throughout 2016, the year in which we will light 100 candles on his birthday cake.

Cindra Kline is an award-winning author, editor, and regular contributor to El Palacio. One of her latest projects, Awakening in Taos: The Mabel Dodge Luhan Story, was chosen as Best Feature Film Made in New Mexico in 2015 at the Santa Fe Film Festival.