Miguel Romero

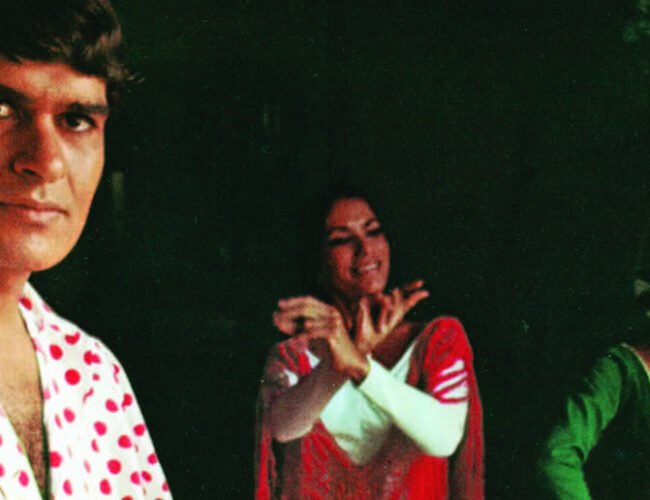

Vicente Romero and troupe were featured in the July 1970 edition of New Mexico Magazine. Collection of Lili del Castillo and Luís Campos.

Vicente Romero and troupe were featured in the July 1970 edition of New Mexico Magazine. Collection of Lili del Castillo and Luís Campos.

WITH NICOLASA CHÁVEZ

In New Mexico the flamenco tradition is now several generations strong. Even though there have been many contributors to the development and growth of flamenco in our state, dancer Vicente Romero (1937–95) is widely credited with creating the vibrant flamenco scene in northern New Mexico that still thrives today.

A Santa Fe native, Romero is often referred to as the godfather of flamenco dance in northern New Mexico. He brought in traditional gitano (Gypsy) performers at a time when New Mexicans were practicing folkloric and regional dances, and fandangos were popular at public fiestas. He inspired generations of future dancers and kick-started the careers of several of New Mexico’s best.

While creating a rich flamenco nightlife in Santa Fe, Romero contributed to a family legacy of musicians. Two of his brothers, Miguel (b. 1943) and Ruben (1946–2007), became renowned in flamenco and Spanish classical guitar. On a brisk, cloudy December morning, I had the opportunity to visit with guitarist Miguel Romero. One of five siblings in the Romero family, he shared his personal history and recollections of days gone by when Canyon Road still had a general store and a restaurant that locals, Hollywood stars, and art patrons frequented.

Chávez: How did the musical tradition begin in your family?

Romero: It all started with my parents, Manuel Romero Jr. and Ruby Roybal. [They] owned a huge hardware store across [from] where The Compound is now. It had a restaurant in back. Everybody came to purchase things from my parents, Los Cinco Pintores [a group of five painters in Santa Fe], Will Shuster. During the 1930s everybody was doing business. People worked for food during the Depression. My grandfather was a bootlegger in those days. The La Fonda was the biggest, most happening place at the time. Billy Palou played there. . . . The restaurant in back of the store was called El Comedor. Vicente loved dance and was always dancing on his own—he was doing the best he could at the time, at the restaurant. He wore Spanish-style costumes with ruffled shirts.

Chávez: When was this?

Romero: About 1951–52, maybe 1953. That Vicente was interested in dance and music came as no surprise to anyone, since our family was already exposed to New Mexican and classical musical traditions. Our uncle, David Romero, played guitar and banjo. He moved to California in the early 1960s. Our auntie, Tony Gutiérrez, played classical piano; her daughter Elizabeth played too. At the time there were only 30,000 people in town. . . . Ruben and I were into motorcycles, threechord guitars. . . . We had a Montgomery Ward guitar, we played for school dances. Our band even went up to Los Alamos. Our mom sang, she would imitate opera singers. Dad was a good musician, studied classical violin at St. Michael’s College during the 1920s.

Chávez: When did Vicente begin dancing?

Romero: There was a studio on Camino del Monte Sol, near El Farol. Louise Licklider was teaching ballet. He started with ballet and then began imitating the fandangos and other basic Spanish dance forms. Lili Baca was also in town, one of the first teachers of Spanish dance, folkloric dance, and dances using capes. . . . It all happened because of Mom, she really exposed us to the arts. She put Vicente in dance class and gave him a space to perform.

It all happened because of the general store on Canyon Road and Billy Valentine. . . . She came in the summer and met the entire family, probably went to Mother’s restaurant and Grandfather’s bar at the José Roybal Store. Billy Valentine was a patron of the arts, from Scottsdale; she would come to Santa Fe during the summers. She took Vicente in as [his] patron. She bought Vicente a brand new Oldsmobile. She was around fifty at the time, a friend of our parents and grandparents. Vicente always had backing; people were always impressed by him. . . . He was extremely charismatic, very handsome, outspoken, studied speech in high school, loved being in front of an audience.

Vicente and his sister, JoAnn, lived with their parents in Los Angeles for several years, where their father worked in the shipyards during World War II. It was JoAnn who first took dance lessons in Santa Fe, and Vicente asked repeatedly to go to class with her. Vicente finished high school at age sixteen or seventeen and went to Los Angeles in about 1953–54. Thereafter, Billy Valentine helped fund his first trip to Spain. Another patron of Vicente was the famous actress Greer Garson. She was so well known that Billy Valentine’s role in Vicente’s career has often gone unnoticed. In Madrid for three years, Vicente studied with Regla Ortega (Paco de Lucía’s aunt), a well-known teacher and dancer. He then became the second male dancer from the United States to join the company of Pilar López, the sister of the famous dancer La Argentinita. Upon La Argentinita’s early death, Pilar López took over the dance company and had a career that spanned four decades. The first American dancer to join the company of Pilar López was José Greco, who also encouraged Vicente to continue studies in Spain. Vicente then moved to New York and formed a troupe with Nana Lorca and Roberto Lorca.

Romero: He was in New York a couple of years. He went up and down the East Coast doing shows at nice nightclubs and resorts. He did a show with Chubby Checker.

Life on the road proved stressful. Vicente became ill with hepatitis. He had to quit his group and spend time in the hospital, and he was unable to dance. He eventually came back to Santa Fe to recuperate.

Everything was going great in New York, he had gigs, a good show, but he had to come home to recuperate after all that travel.

Vicente returned to New Mexico in 1961, where he started teaching and creating bilingual educational programs throughout the state. Miguel recalled that at first, Vicente used recorded music for teaching until he met a guitarist named Lew Critchfield (aka Luís Campos), “a very serious player and student.” They did a performance together at Saint Francis Auditorium, in the New Mexico Museum of Art. According to Miguel, Critchfield and Romero “blew everybody away. Santa Fe had not seen flamenco. . . . Vicente had electric, lightningspeed footwork.”

Vicente became known as much for his own talent as for his knack for bringing together top musicians and performers from Spain. He believed in providing a total flamenco experience: one never did a show without a singer, since cante is the most important aspect of the art form. His own experience and that of guest artists, who then also taught formally or informally, transmitted the art of flamenco to students and aficionados from near and far. Both of Vicente’s brothers, Miguel and Ruben, got their early start in flamenco and Spanish guitar because of Vicente.

Chávez: How did you and Ruben get into flamenco?

Romero: Vicente started introducing me [and Ruben] to flamenco. Back then when it was introduced, we saw José Greco on TV, but you don’t get the explosive power that you see in a small live venue . . . awesome. We all saw Carlos Montoya on The Ed Sullivan Show. I was aware that Carlos Montoya did tremendous finger work, trémolos [rapid, yet soft movements of the right hand]. I had a steel-string guitar and was trying to pick up using records. When Lew came along it was a godsend, he started me. Vicente became friends with Lew. Lew’s mother called Vicente’s mother and said, “Maybe we should get them together,” since they both did flamenco. Then Vicente was able to do what he knew. They worked together until Lew went off to Spain. Then Vicente brought in the Patterson brothers, Eric and Bruce Patterson. Eric ran a bookstore in Albuquerque. Clarita [García de Aranda, the mother of the founder of the National Institute of Flamenco, Eva Enciñias- Sandoval] was having parties and jam sessions at her house back then; she sang a bit. She knew and studied some of the [Spanish] dances. Eric liked to accompany Clarita. Eric and Bruce learned from Julio de los Reyes. Julio later played with Vicente at Zambra [an establishment started by Vicente and his partner, Jorge Midón, in 1972, after Vicente left El Nido; present-day El Gancho]; he also became a painter. Bruce Patterson worked first with Vicente in 1964. He was hanging out with Clarita and playing for her in 1962–63, when Vicente was teaching in Albuquerque. Vicente met Clarita through Eric; the kids [Clarita’s children] were really small and doing palmas [the rhythmic hand-clapping that accompanies flamenco guitar, singing, and dancing]. We were playing on steel strings, trying to fake it, because we had seen it on television. Lew Critchfield helped us and taught us. We already had training in electric guitar, had developed our left hands, [and] began working on the right hand right away. We also got into classical music, Andrés Segovia; we were still learning at Rancho Encantado after leaving El Nido.

Chávez: How did El Nido begin?

Romero: Ray Arias had the popular watering hole in the late 1950s. Vicente brought it to Ray’s attention. [It started in] the Zozobra Room, which had a painting [of Zozobra] by Will Shuster. It was done on canvas so the painting could be removed later on. You had the Shusters, [Jozef] Bakos, Freemont Ellis, and movie stars were hanging out there. Even Desi Arnaz came to Santa Fe, I saw him at the bar at La Fonda. Santa Fe is a place where a lot of people came. There were lots of movie pictures in Santa Fe, lots of actors, they all ended up at El Nido, a really neat watering hole, a great bar, was close by away from town. Ray Arias was a super host, like Vicente. He [Ray] was friendly and a politician. It was the perfect place for flamenco to start. . . . When I was playing at Rancho Encantado, I made friends with Jimmy Stewart and Gene Kelly. I was

twenty-five.

Chávez: When did you start playing at El Rancho Encantado?

Romero: About 1963 or ’64; the owner of Rancho Encantado had been going to El Nido. We had excellent guitars, Ramírez guitars, they made beautiful sound. [Rancho Encantado] had the perfect atmosphere, ambience; it continued even after El Nido and Zambra. I played the first few months at El Nido, but Vicente had plenty of guitarists. I got more into classical music. Classical is more poetic, and you can play it alone. Flamenco is very energetic and exciting. Vicente brought in René Heredia to play at El Nido. I had no idea that René had played for Carmen Amaya for five years, after Sabicas [Agustín Castellón Campos] went off to play solo. Heredia was inspired by [French gitano flamenco guitarist] Manitas de Plata. . . . [Early on] people were freaked out with [flamenco] because it was not around that much. Being the first ones, people think of us as genius. El Nido was in the paper all the time. Tourism was getting very strong during the late 1950s, early 1960s. The Santa Fe Opera was coming about. People went to the opera first and then to see the flamenco show at El Nido.

Canyon Road was like a little artist colony; Santa Fe was an art center before the opera and before El Nido. The opera was a small opera house, outdoor place, all the people studying would come. . . . It was a little ahead of flamenco, a little sooner. The two things coincided together. Flamenco made it on its own merit, had its own audience. . . .

We had the Rockefellers, Maria Callas, Grace Kelly; our entertainment was perfect for them. The classical and the romantic music, perfect for dinner, a little flamenco for a little excitement. We threw in a little jazz, a little boogie-woogie; variety saved us on guitar. Ruben became quite a guitar phenomenon. He had his first film, Simple Treasures, in 1981–82, done by László Kovács, the same guy who did Easy Rider. It was scenes of New Mexico put to music by Ruben, who wrote it and did the arrangements. It got international play.

Guitar became popular because of flamenco. El Rancho Encantado was the only place for classical [at the time]. Vicente at this time was doing gigs at La Fonda, El Farol; he did banquets, weddings. During the off-season, from El Nido he went to the Robin Hood Inn on 4th Street in Albuquerque. Ray Arias became Vicente’s impresario. He died in a car accident in 1968, two years after the Robin Hood Inn, after the summer at El Nido. That changed Vicente’s life and career; he had to become his own boss, manager, and impresario. Arias’s wife didn’t want to continue El Nido anymore; she sold the business. Vicente moved to La Zambra at El Gancho. He was there for one year, nine months. Carlos Montoya came to Zambra and did his rasqueados [quick, rhythmic motions of the entire right hand to emphasize beats or phrasing] and fast trémolos. His fast trémolos blew me away! María Benítez was here only during the summers; she did El Nido; she taught and did La Zambra. In 1982–84, guitarist Carlos Lomas brought in José Greco at La Fonda.

By the 1980s the flamenco scene had already been established in Santa Fe for more than a decade, thanks at first to Romero, then to Benítez, Lomas, and others. In a separate discussion, Lomas recalled that there was enough audience for several venues to run simultaneously. Each group had its shows six nights a week, but performers had different nights off and attended each other’s shows. After parties, late-night jam sessions took place. Another establishment, El Farol, known as Santa Fe’s oldest bar and restaurant, became a known local hangout, where all walks of life from various flamenco communities in Albuquerque, Taos, and Santa Fe met.

Chávez: How and when did El Farol become a known flamenco hangout?

Romero: We would go there for drinks after shows, had late night juergas [jam sessions]. Vicente would get up and dance.

We would have a jam session, impromptu, get the guitars out of the car. It is the best way to do flamenco . . . just break out the tequila and jam. . . . Vicente would do the martinete [a dance that mimics the sounds of the blacksmith at his forge] with the anvil. Flamenco has changed, it is different. [Back then] there was a whole lot to flamenco, eight to ten different styles of soleares [one of the basic forms, or palos, of flamenco]. . . . Vicente and María were into all the old stuff and all the regional dances. They showed the beginning [origins] of flamenco and where it comes from. Vicente was very young [when it all started]. He worked for a long time, but burned out dancing two shows nightly.

Vicente enjoyed an illustrious career. In Santa Fe he danced two shows a night, six nights a week during summer season. He spent a portion of his life touring and educating throughout New Mexico’s rural communities and faraway towns and villages. He also guest starred in many national shows, and in 1991 he joined the company of the man who first inspired him and encouraged him to go to Spain for further study, José Greco. In 1995 Vicente suffered a heart attack after a performance with Greco’s company at the Joyce Theater in New York. His last dance was an alegría, one of Romero’s specialties, showcasing the upbeat, joyous side of flamenco for which he was so famous. He received three standing ovations for his final dance. Miguel remembers Vicente with a smile: “It all would never have happened without Vicente going to Spain. I can’t believe I played with a guitar player who accompanied Carmen Amaya for five years!”

Nicolasa Chávez is curator of Latino/Hispano/Spanish Colonial Collections at the Museum of International Folk Art. She recently curated Flamenco: From Spain to New Mexico and wrote the accompanying publication, The Spirit of Flamenco (Museum of New Mexico Press, 2015). Previously she co-curated The Red That Colored the World and contributed to the accompanying publication, A Red Like No Other (Rizzoli Press, 2015).