Blood Oaths

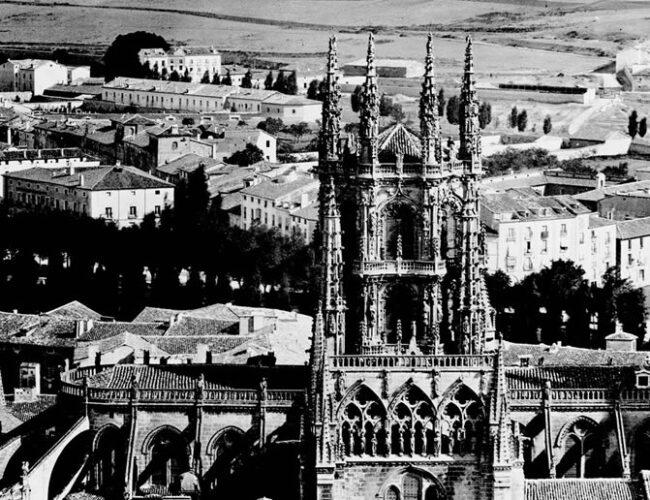

Burgos was home to many of Oñate’s ancestors of Jewish descent. This image shows a view of the cathedral and city from the royal castle, ca. 1860–70. Photo by J. Laurent. Library of Congress

Burgos was home to many of Oñate’s ancestors of Jewish descent. This image shows a view of the cathedral and city from the royal castle, ca. 1860–70. Photo by J. Laurent. Library of Congress

Piety and privilege collide in Juan de Oñate’s Jewish-converso lineage.

BY JOSÉ ANTONIO ESQUIBEL

Don’t think that you injure me by calling my fathers hebrews. of course they were, and thus i want them to be.

—Attributed to Alonso de Cartagena, ancestral cousin of Juan de Oñate, in Diálogo de Vita Beata, by Juan de Lucena, 1502

Fractured Faiths: Spanish Judaism, the Inquisition, and New World Identities, currently at the New Mexico History Museum, tells the history of the Jews of the Iberian Peninsula, many of whom were forced to convert to Christianity or expelled from the peninsula for rejecting conversion. Least studied are descendants of converts who practiced Christianity and also honored the memory of their Jewish lineage, including individuals that came to the Spanish Americas in service to God and king. One such group of sincere Catholic conversos (converts) is found in the maternal family lineage of Don Juan de Oñate, among others who settled Spain’s far northern frontier regions of the Americas.

Oñate’s landmark arrival in New Mexico in 1598 introduced the cultural legacy of Spanish Iberia to the region. In his company were about 300 individuals from throughout Europe, mainly the Iberian Peninsula and the Spanish regions of what is today central and northern Mexico. Oñate’s own ancestry is a quiet testament to the diversity of Spanish culture, including Jewish-converso family roots. (For a thorough introduction to conversos and crypto-Jews in Spain and New Mexico, read “The Exile Factor,” El Palacio 121, 2).

The acceptance of Christianity by two of Oñate’s Jewish ancestral families was a prominent part of family history from the 1390s into the 1600s. The descendants of these families, the Maluendas and the Santa María-Cartagenas (Ha-Levis), did not attempt to hide their Jewish origins or pretend to be of “Old Christian” heritage. Cristianos viejos, Old Christians, was a term used to identify individuals without any Jewish or Moorish ancestry. Cristianos nuevos, New Christians, referred to individuals whose parents or immediate ancestors converted from Judaism or Islam to Christianity. Oñate’s New Christian family members made valuable contributions to Spanish society as scholars, local officials, crown-appointed officials, and clergy of the Catholic Church

In 1625, living back in Spain at age seventy-three, Juan de Oñate sought entry into the prestigious Spanish religious military Order of Santiago. Acceptance into the order required a prueba de limpieza de sangre, proof of Old Christian pure-blood lineage to at least the third generation. The prueba statutes originated in the mid-1400s as a direct reaction to the large number of Jewish conversos (like Oñate’s ancestors) seeking positions in public and religious institutions. This was the culmination of decades of fierce anti-Semitism that fostered discrimination against descendants of New Christians regardless of their sincere adherence to Christianity.

All one in christ? Old Christians Against New Christians

During the 1300s, at the request of local government leaders of towns and cities, the royal court of Castilla issued decrees prohibiting Jews from occupying positions of local governance. What began as anti-Semitic rhetoric in the mid-1300s evolved into widespread acts of violence against Jews in 1391, including murder and the confiscation and destruction of property in numerous cities and towns of the kingdoms of Castilla and Aragón.

Even after numerous Jews converted to Christianity in the face of violence, New Christians, as descendants of Jews, became targets of increasing anti-Semitic discrimination. The entry of numerous New Christians into positions of civic and religious governance between 1391 and 1440 generated disaffection among some Old Christians, including some clergy, due to resentment around a loss of control of financial resources and diminished political influence. The anti-converso ideology developed by adversaries of New Christians during this period emphasized political opposition to their integration into Christian society rather than accusations of religious insincerity. This changed with mounting social and political tensions.

In the late 1440s, Old Christian city administrators of Toledo augmented the prevailing anti-converso ideology of discrimination based on ancestry to include accusations that conversos held Jewish beliefs and practiced Jewish rites in secret. Slogans vilifying conversos as secret Jews rapidly spread among the general population. Conversos were also regarded as heretics, accused of conspiring as a group to bring ruin to Christendom by means of their mass conversion. As a result, in Toledo in 1449, conversos were arrested and dragged into religious court, accused of Judaizing, sentenced to death, and burned at the stake; their property was confiscated.

This was the beginning of decades of public discourse that questioned the religious sincerity of New Christians, giving rise to distrust and the erroneous belief that the majority of converts were crypto-Jews seeking social advantages while still practicing Judaism in secret. Although Church prelates and the king condemned the acts of violence in Toledo and punished the perpetrators, an increasing number of the general populace began to harbor ill will toward New Christians and perpetuate suspicions about their religious sincerity.

In the wake of this growing hostility, adversaries of the conversos developed strategies to exclude them and their immediate descendants from occupying positions in a variety of social institutions. Among these strategies were the pruebas de limpieza de sangre, which sought to denigrate the ancestry of Christians with Jewish lineage and cast aspersion on the sincerity of their family’s authentic, multigenerational acceptance of Christianity. These proofs became necessary in order to attain various positions in Spanish society, compromising the viability of New Christian candidates.

The assault on the religious sincerity of Christians with Jewish antecedents fractured the Christian faith in the kingdoms of the Iberian Peninsula. High-ranking officials of the Roman Catholic Church and the royal crown of Castilla rebuked these tactics of discrimination. Prelates of the Church regarded the rationale for the purity of blood statutes as heresy—an erroneous interpretation of Catholic doctrine. Pope Nicholas V denounced the statutes in a papal bull, or decree, released in September 1449, emphasizing that “all Catholics are one body in Christ.”

Catholic theologians of Jewish descent, such as Alonso de Cartagena, the bishop of Burgos and an ancestral cousin of Juan de Oñate, drew from scripture and Catholic doctrine to argue for unity between Old and New Christians. Although sound in theological reasoning, the arguments did not dismantle opposing beliefs, and the fracturing of Christianity expanded. Some Catholic clergy further promoted anticonverso ideology, leading to the eventual establishment of the Inquisition in Castilla and Aragón in 1480 and the subsequent command of King Ferdinand and Queen Isabel that forced the expulsion of Jews from Spain in 1492.

Juan de Oñate’s Christian ancestors of Jewish lineage endured extreme social, political, and religious adversity following conversion from Judaism in the late 1300s. Nonetheless, they managed to make remarkable contributions to Spain’s Christian society, a legacy that Oñate emulated in his service to crown and Church in New Mexico and for which he sought entry into one of the most prestigious Spanish religious military orders.

Oñate’s Proof Of Christian Lineage

When Don Juan de Oñate prepared his application into the military Orden de Santiago in 1625, he began with the identification of his parents, his paternal grandparents, and his maternal grandparents. The process of proving purity of blood lineage followed a pattern of gathering testimony from community members, usually male elders, in towns in which a person’s immediate ancestors were born or lived. In the case of Oñate’s proof, witnesses from the towns of Oñate and Narria, in the Basque prov ince of Guipúzcoa, confirmed his descendancy from the hereditary manor house of the Lords of Narriahondo, Basque nobles of Castilla descended from cristianos viejos.

The ancestors of Oñate’s mother, Doña Catalina de Salazar, served in the royal court of Spanish monarchs from the late 1300s to the mid-1500s. One of her family lines traces back to Jewish families that converted from Judaism to Catholicism in the late 1300s. To document the Christian status of his maternal lineage, Oñate included in his application the already confirmed proof of lineage of his great-uncle, Maestro Luis de la Cadena, brother of Doña Catalina de la Cadena, Oñate’s grandmother. In 1534, when Maestro Luis prepared to complete his doctorate in Catholic theology at the University of Alcalá, the testimonies of numerous witnesses, mainly from the city of Burgos, attested to the Christian character of his immediate ancestors. The witnesses testified truthfully that his immediate ancestors were born Christians. They chose not to acknowledge what was well known: both of his parents, Pedro de Maluenda and Doña Catalina de la Cadena, were descended of Jews.

The earliest ancestor mentioned by witnesses was Alvar Rodríguez de Maluenda, the direct paternal great-grandfather of Maestro Luis and the third great-grandfather of Juan de Oñate. Alvar’s father, Juan Garces de Maluenda, a man of Jewish lineage, arrived in Burgos before 1391 and married María Núñez, a Jewish woman of the local Ha-Levi family. This family, including the celebrated and learned Rabbi Selemoh Ha-Levi (1350–1435), accepted Christianity just before the violent anti-Jewish riots of August 1391.

Oñate’s Jewish and New Christian Ancestral Relatives

Selemoh Ha-Levi, rabbi of the jurisdiction of Burgos, was of course well versed in the Torah, Talmud, and Jewish law. He also studied Arab philosophy and read Greek philosophy and Latin works, including Catholic theology. Selemoh accompanied Rabbi Samuel Abravalia on a mission to speak with the pope in Avignon about mistreatment of Hebrew people by Christians. He also entered into the service of King Juan I of Castilla. In 1390 Selemoh experienced a profound spiritual transformation, leading him to accept Christianity. His new conviction influenced his immediate relatives and other Jews of Burgos to receive baptism and to begin practicing the Catholic faith

Adopting a Christian name, Pablo de Santa María, Selemoh professed ordination vows as a priest of the Roman Catholic Church. Selemoh’s careful choice of a Christian name spoke volumes about his conversion and that of his extended family. With the given name of Pablo, he extended tribute to the influence of the epistles of Saint Paul and drew a direct connection to the sharp conversion of this saint, who came to believe in Jesus as the Messiah. Selemoh even wrote, “Paulus me ad findim convertit” (“In the end, Paul converted me.”), indicating that he and his brethren not only considered themselves akin to the Jews who were the first Christians, they were also influenced by Christian writings with an emphasis on the messianic prophecies of the Old Testament. In choosing the surname of Santa María, Selemoh and his extended family recognized an ancestral kinship with Saint Mary, who was popularly known as a descendent of the tribe of Levi. In his writings, Pablo de Santa María emphasized that as Levites he and his relatives were related to Saint Mary and thus to Jesus. Pablo de Santa María studied at the University of Paris, where he received his doctorate in Catholic theology. His writings provide insight into his spirituality, religious thought, and views of being a Christian of Jewish lineage, as well as the prophetic links between the writings of the Old and New Testaments. This view of continuity between Judaism and his conversion to Christianity is apparent in the following statement: “Although other saints preceded Abraham in time, nevertheless Abraham was the first among all the saints, first in separating himself from the body of infidelity—he was first also in receiving from God the promise of the coming Messiah.”

Three sons of María Núñez (Ha-Levi) followed in the footsteps of their uncle, Pablo de Santa María, and took Catholic religious vows. This family, like other New Christians, did not hide their Jewish background. They viewed their conversion as a form of continuity between Judaism and Christianity, like the Jews who became the first Christians.

Upon their deaths, the bodies of María Núñez and Juan Garces de Maluenda were laid to rest in a chapel of the Convento de San Pablo. By the beginning of the 1500s, the Maluenda-Nuñez descendants founded their own family chapel within this convento and christened it the Capilla de las Once Mil Virgenes, where many members of this family were interred.

Confirmation of “Old Christian” Lineage of Jewish Descent

The fact that Maestro Luis de la Cadena received confirmation of his Christian lineage as part of a prueba de limpieza illustrates more attention was paid to verifying character through “purity of faith” than through literal “purity of blood.” Among the Maluenda family’s Christian character witnesses was the influential Pedro Jiménez del Castillo, secretary of Emperor Maximilian in Flanders and secretary of the emperor’s son, King Felipe. Jiménez del Castillo attested that none of Maestro Luis’s parents, grandparents, or great-grandparents were ever condemned for practicing Judaism, and all were Christians of good standing and honor.

The rules dramatically changed in 1544, when Archbishop Juan Martínez Siliceo instituted a more stringent application of the statutes of limpieza in Toledo. He intended to specifically exclude individuals of Jewish lineage from entering the clergy of the local cathedral. Although Roman Catholic Church officials opposed such statutes in the 1400s, by the mid-1550s, Pope Paul IV and King Felipe II endorsed them. The requirement of proving limpieza de sangre gained momentum and became widespread. In Castilian society, literal blood lineage, which was associated with ancestral cultural heritage, was now the litmus test for unimpeachable familial religious sincerity.

Of course, the new interpretation of the statutes of limpieza caused difficulty for descendants of the Ha-Levi clan. Maestro Luis de la Cadena clashed with Archbishop Martínez Siliceo and was suspected of instigating the writing of a treatise against the statutes. Either Martínez Sileceo or his allies denounced Maestro Luis to the Inquisition in 1551. Fearing the worst, he managed to escape to Paris, sacrificing his position as chancellor of the University of Alcalá, a position he had held since 1537. Maestro Luis remained in France until his death.

In an extraordinary act of favor, Pope Clemente VIII issued a 1603 bull confirming and extending Old Christian status to the descendants of Pablo de Santa María. The following year, King Felipe III issued a royal decree also confirming the limpieza de sangre of the Santa María descendants. Although other Jewish-converso families received titles of hidalguía (lower nobility), none were granted the same official extension of Old Christian status.

Despite these remarkable measures, the Jewish ancestry of the Maluenda–Santa María family emerged as an impediment in the next century and across the ocean. In 1619, in Mexico City, the application of Bernardo Vázquez de Tapia as an official of the Inquisition was delayed by the investigation into the ancestry of his wife, Doña Antonia de Rivadeneira y Oñate, a niece of Juan de Oñate and a second great-granddaughter of Pedro de Maluenda and Doña Catalina de la Cadena. Witnesses in this case recalled that the Maluendas were descendants of “María de Santa María y Cartagena, a Jewess woman.” It was not until 1640 that Vázquez de Tapia received favorable approval of his and his wife’s lineages. The delay may have been for political reasons and not because of religious infidelity by either one of them.

But when Juan de Oñate submitted his application in 1625 to join the Order of Santiago, he confidently included the proof of lineage of the Maluenda family. With additional testimony from members of the communities of Zacatecas, Mexico City, Oñate, Narria, Granada, Madrid, and Burgos, the case for his Old Christian status was accepted.

It is likely that a number of individuals who came with Juan de Oñate to New Mexico were also descended of Christians with Jewish lineage, but it is very challenging to determine with historical and genealogical documentation which families that settled New Mexico were descendants of Jewish converts to Christianity. By 1609 fifty soldiers were left as settlers in New Mexico, most with families. Many of these individuals rank among the most common ancestors of people with deep Hispano roots in New Mexico. None of these families’ genealogies have yet been traced further than the mid-1500s; they include Archuleta, Baca, Carvajal, Durán y Chaves (Chávez), Gómez, Griego, Luján, López Holguín (Olguín), Martín Serrano (Martínez), Montoya, Robledo, Romero, Márquez, Pérez de Bustillo, and Varela (Barela). Although suppositions have been made about families who may have been descended of Jewish-conversos, it is still necessary to trace lineages into the 1400s and even the late 1300s in order to confirm such descendancy.

DNA Testing

Because of the lack of documentation, there has been recent interest in DNA testing. Although DNA does not reveal religious affiliation, it provides some hints that a few Spanish lineages of New Mexico may descend from individuals who practiced the Jewish faith. This is based on gathering DNA samples of modern-day clans of people with a long history of practicing Judaism and matching samples from Hispano New Mexican males. Although DNA studies show that there is no single DNA haplogroup (genetic category) among people with ancestral Jewish roots, a high percentage of Jewish men have the genetics of Y-DNA Haplogroup J. However, this haplogroup is also common among non-Jewish men with ancestry in the Middle East, North African, and throughout Europe. There are men with roots in New Mexico whose Y-DNA belongs to Haplogroup J, which may be a hint, but is not proof, of Jewish ancestry.

The New Mexico DNA Project is actively collecting DNA of men and women with Hispano roots in New Mexico. It will require a large sampling of individuals in order to conduct comparative analyses of DNA matches in conjunction with genealogical data to make a link to common ancestors. This effort is in the early stages, and the need to trace family lineages beyond the mid-1500s is critical for this work. There is the likelihood that lineages similar to that of Juan de Oñate will be uncovered. It is highly probable that at least a few individuals who came to New Mexico in service to the Spanish Royal Crown and the Roman Catholic Church were descendants of Christians of Jewish lineage. One such individual was Fray Cristóbal de Salazar, also a descendant of the Maluenda-Ha-Levi family and Oñate’s cousin.

The expedition that Oñate led into New Mexico embodied a deliberate intention to establish the Christian religion among the indigenous people of the northern frontier. His cousin, Fray Cristóbal de Salazar, is remembered for delivering the first Catholic sermon along the banks of the Rio Grande at El Paso in September 1598. He helped bring the Christian faith to the Tewa Indians of northern New Mexico and died en route to Mexico City in 1599 near a small mountain range still known today as the Fray Cristóbal Mountains, in southern New Mexico.

In spite of centuries of generations of social adversity, two descendants of Christians with Jewish lineage led the effort that established Christianity in New Mexico, a faith that has endured to the present day

José Antonio Esquibel is a genealogical researcher and historian. With France V. Scholes, Eleanor B. Adams, and Marc Simmons, he is coauthor of Juan Domínguez de Mendoza: Soldier and Frontiersman of the Spanish Southwest, 1627–1693 (UNM Press). In 2009 Juan Carlos II, king of Spain, invested Esquibel as a knight of the Orden de Isabel la Católica for his dedication to preserving the history of Spain and Spanish heritage in New Mexico.

Fractured Faiths: Spanish Judaism, the Inquisition, and New World Identities runs through December 31, 2016, at the New Mexico History Museum. It is the first museum exhibition to explore this subject in depth. Josef Díaz and Roger L. Martínez-Dávila, the curators, have traveled to collections in Mexico and Spain, as well as the United States, identifying the 150 or so objects in the exhibition to tell this intriguing 500-year-old story, from the Jews of Spain to the conversos of New Mexico. These priceless historic objects have been hand carried to New Mexico by couriers from each lending institution. The late Seymour Merrin’s generous initial donation made this exhibition possible. A catalog with the same title as the exhibition, edited by Roger L. Martínez-Dávila and Ron D. Hart (Fresco Press), includes articles by authorities on this subject from the United States, Spain, and Mexico.