Bohemian Rhapsody

Will Shuster’s artistic community

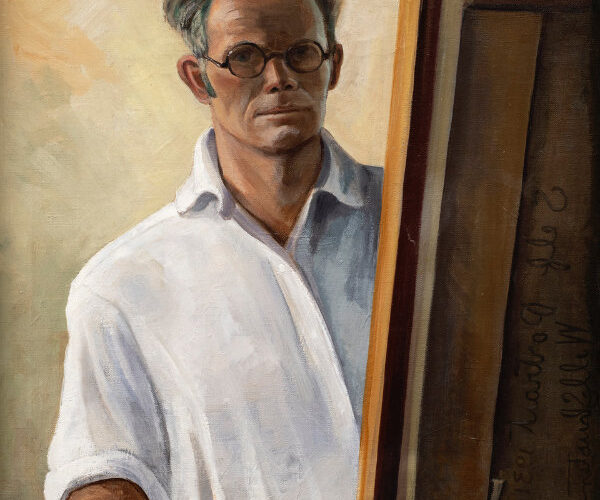

Will Shuster, Self Portrait, 1931. Oil on canvas. 30 × 24 in. Courtesy the family of Will Shuster, Santa Fe, and Zaplin Lampert Gallery, Santa Fe.

Will Shuster, Self Portrait, 1931. Oil on canvas. 30 × 24 in. Courtesy the family of Will Shuster, Santa Fe, and Zaplin Lampert Gallery, Santa Fe.

By Christian Waguespack

A century ago, in 1920, serious health issues brought Pennsylvania-born artist William Howard Shuster (1893– 1969) to New Mexico, beginning forty-nine years of creativity, exploration, and community engagement. Though he received some fine-arts training in Philadelphia, it was not until he experienced the inspiration of Santa Fe that he decided to dedicate his life to art. Almost immediately, he famously joined four other young bohemians to become Los Cinco Pintores, and integrated himself into Santa Fe’s burgeoning Modernist art scene. He soon made a reputation for himself as an eccentric and passionate member of the community with an unsurpassed lust for life.

Shuster embraced the unique beauty of New Mexico, from Carlsbad Caverns to Cañoncito and the Badlands. The artwork he left behind illuminates the natural beauty and rich cultural heritage of the state that gave him a new lease on life. Shuster quickly moved to the center of the Santa Fe art scene, becoming close friends with American Modernist painter John Sloan and establishing himself as a member of one of the city’s first artist communities.

The five artists of Los Cinco Pintores comprised a group of Modernist painters with an affinity for presenting fine art to the masses. December of this year marks a century since their first show at the Santa Fe institution that was then called the Museum of Fine Arts. In celebration and commemoration, this year the New Mexico Museum of Art presents A Fiery Light: Will Shuster’s New Mexico to highlight the artistic legacy he developed in Santa Fe and throughout the state and illustrate the artistic relationships he forged here.

Los Cinco Pintores

Five painters—Jozef Bakos, Fremont Ellis, Walter Mruk, Willard Nash, and Shuster—came together in the early 1920s at a time when Santa Fe was beginning to establish a distinctive identity as an arts colony. These five were part of a younger, more avant-garde scene in the city, and had not been able to make much headway into the artistic community of more established artists thriving in Santa Fe and Northern New Mexico. Ellis came up with the name “The Five Painters,” but his wife, Laurencita Gonzales, suggested the Spanish “Los Cinco Pintores” to reflect the culture of the area. In El Palacio’s November 1921 edition, Bakos published a manifesto for the group, stating its “endeavor to reach out to the factory, the mine and the hospital, as well as the gallery, and it aims to awaken the worker to a keener realization and appreciation of beauty, thus helping to develop the art instinct which lies latent in every human mind.”

As a group, they were more interested in the potential of art enriching the lives of everyday people than a dedication to a common aesthetic or philosophy of art. Commonly—and affectionately—referred to as “five little nuts in five mud huts,” they built adjacent adobe homes on Camino del Monte Sol, effectively creating Santa Fe’s first art-colony road.

John Sloan and the Aschcan School

Sloan and Shuster were introduced in 1920 over dinner by the owners of the boarding house on what is now the corner of Guadalupe Street and San Francisco Street, where they both stayed when they first came to Santa Fe. This fortuitous encounter led to a lifelong friendship, and resulted in Sloan, who was twenty-two years Shuster’s senior, becoming a mentor to the aspiring young artist. Sloan first visited New Mexico in 1919 on the advice of Robert Henri, who, some four years earlier, had convinced the New Mexico Museum of Art’s founder, Edgar Lee Hewett, of the importance of Modern art and who was seminal to the establishment of the museum. Sloan and Henri were prominent members of the Ashcan School in New York, a group of realist artists focused on representing the lives of everyday people and the poorer neighborhoods of the city.

Sloan brought this interest in finding inspiration in ordinary life with him to New Mexico. Shuster picked up these themes in his own work. Over the next thirty years, Sloan continued to visit New Mexico regularly, painting primarily genre scenes of community life, such as Pueblo religious ceremonies.

Pueblo life and culture were a reoccurring theme for Shuster, too. While many earlier depictions of Native ceremonies could be documentary in nature, skewing to the anthropological, modernists like Sloan and Shuster aimed to capture the feeling and expression of these ceremonies, pulling the viewer in close to the action. As time went on and Sloan became more conscientious in his representation of Native peoples, his paintings pull back, offering a more realist and respectful representation of these ceremonies, similar to the composition we find in paintings by Shuster such as The Santo Domingo – Corn Dance. Shuster would have been familiar with the evolution of Sloan’s treatment of this subject, and Sloan’s work certainly informed the way Shuster approached his art; but Shuster always remained true to his own vision. Sloan enthusiastically encouraged Shuster to paint the life of the Native people of New Mexico, and for both artists it was a staple of their regional subject matter.

Sloan’s influences on Shuster went beyond local subject matter. He first sparked Shuster’s interest in printmaking when he sent him a textbook on the principles of etching. Shuster’s zest for the new medium often distracted him from his painting. In a letter to Sloan in 1925, he writes, “Painting has been at a standstill because of the etching splurge, but somehow or other it doesn’t bother me much.” Shuster made large editions of etchings focused on picturesque regional scenes and was especially fond of making Christmas cards. He was particularly taken by the populist nature of printmaking and made his prints with an eye to accessibility and affordability; the large editions made them available to any who wanted one. He priced them within the budget of tourists with even the most limited of means. His etchings earned attention outside of New Mexico, with the New York Times publishing a glowing review of a series of prints exhibited at the Society of Independent Artists in New York City in 1923.

Zozobra

When it came to making art for all, undoubtedly Shuster’s most communitarian contribution to Santa Fe is Zozobra—a soaring cloth and paper marionette representing Old Man Gloom that is burned every year in late summer. It is almost impossible to imagine Santa Fe without Zozobra. One of Santa Fe’s most unique and spectacular community celebrations, the dramatic and therapeutic group catharsis that is the burning of Zozobra is both a staple of local culture and a magnet for visitors to Santa Fe.

The roots of Zozobra reach deep into the fertile artistic soil of Santa Fe. The first burning of Zozobra was the result of an artistic collaboration between Will Shuster and Gustave Baumann in 1924. Their inspiration came from the Yaqui Indians of Mexico who, during the nation’s Holy Week celebrations, reportedly led a donkey carrying an effigy of Judas around their village. At the end of the day, the effigy, which is filled with firecrackers, is set alight. Shuster and his good friend E. Dana Johnson, a newspaper editor, came up with the name Zozobra. As the story goes, they flipped at random through a Spanish-English dictionary landing on the word that in Spanish means “anguish, anxiety, gloom,” or “the gloomy one.”

Shuster and Baumann burned the first Zozobras at private parties attended by the other artists in the community. The ceremony was introduced into the city’s annual Fiestas celebration in 1926. The burning of Zozobra continued through the devotion of Shuster until 1964, when he passed responsibility for the event to the Kiwanis Club of Santa Fe, which has kept his cultural legacy thriving ever since.

When he died in 1969, Shuster—who served in the United States Army in World War I—was buried in Santa Fe National Cemetery, in the shadow of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. His death was an occasion for regional mourning. In its coverage of Shuster’s funeral, The Santa Fe New Mexican reported: “It snowed last Thursday when they buried Will Shuster, and later that snow turned to rain and sleet. In the skies, Zozobra reigned, but the people who attended the funeral service went along out to the cemetery to be with their old friend to the very last.”

—

A Fiery Light: Will Shuster’s New Mexico is currently scheduled to be on view at the New Mexico Museum of Art until July 25. Due to uncertainty related to the COVID-19 pandemic, please check nmartmuseum.org for updates before planning your visit.

Christian Waguespack is curator of twentieth-century art at the New Mexico Museum of Art in Santa Fe.