We’ve Got a War to Win!

A new book from the Museum of New Mexico Press details artist Eva Mirabal’s quiet subversion.

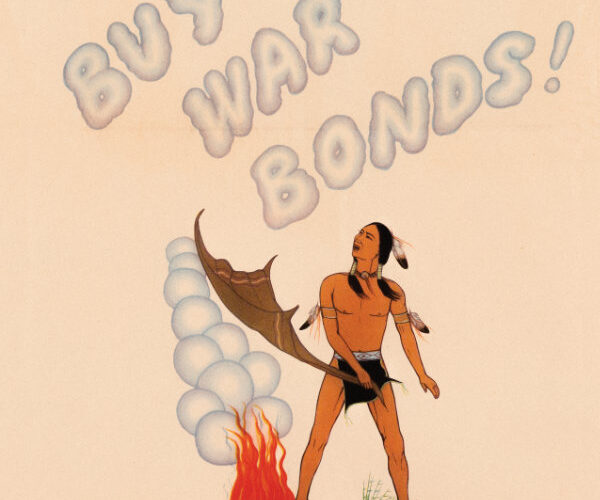

Eva Mirabal, Buy War Bonds, 1942. Offset poster, 19 ¾ × 16 1⁄8 in., unframed. Fred Jones Jr. Museum of Art, University of Oklahoma, Norman. The James T. Bialac Native American Art Collection, 2010.

Eva Mirabal, Buy War Bonds, 1942. Offset poster, 19 ¾ × 16 1⁄8 in., unframed. Fred Jones Jr. Museum of Art, University of Oklahoma, Norman. The James T. Bialac Native American Art Collection, 2010.

By Lois Rudnick and Jonathan Warm Day Coming

The following is an excerpt from the third chapter of Eva Mirabal: Three Generations of Tradition and Modernity at Taos Pueblo (Museum of New Mexico Press, 2021). Eva Mirabal (Eah-Ha-Wa, Fast Growing Corn, 1920–1968, Taos) studied at the Dorothy Dunn Studio Arts Program at the Santa Fe Indian School, where she was a favorite of the founder and served as an assistant to Dunn’s replacement, Geronima Montoya (P’Otsunu, 1915–2015, Ohkay Owingeh). By the time she was 20 years old, Mirabal was exhibiting at museums and galleries across the nation.

During World War II, Mirabal enlisted in the Women’s Army Corps in the US Army (1943–1946), the only WAC assigned as a full-time artist. She was likely the first Indian artist to publish her own comic strip, the subversive G.I. Gertie, which she published monthly for the nationally distributed newspaper, AIR WAC. During the same period, she worked on two significant murals. After the war, she was a visiting art instructor at Southern Illinois University. Following her return to Taos Pueblo in 1947, to help care for her ailing mother, she was a student at the Taos Valley Art School (1949–1951). Throughout her lifetime, her paintings and murals received national acclaim.

CHAPTER III: Eva Mirabal and World War II (1943–1946)

In 1942, Eva’s last year at Santa Fe Indian School, she entered a national poster contest, sponsored by the US Treasury Department, which was held in Indian schools throughout the nation to help sell war bonds. Hers was one of three winning posters, now preserved at the Library of Congress as well as in other museum collections. Indian iconography was popular during World War II. Most of it was stereotypical (war chief icons and lingo—“braves,” “warpath”—were especially popular). Eva’s depiction of the warrior in Smoke Signals seems intended to remind her fellow Americans that an earlier Indian mode of communication predated modern technologies and that the original “Native” Americans were as patriotic as any other Americans.

The introduction to the award-winning posters by the US Treasury Department, ironically, drew on stereotypes of Indian “savagery,” which now benefited the nation that had decimated Native lands and cultures: “All over the country American Indians still in school are making posters that tell how they feel about the war. … Some of these poster-makers say these things differently because they see America and the war with a special vision. … They see the war as their fight—to be fought with their ancient courage and cunning.”

As Jeré Bishop Franco points out in Crossing the Pond: The Native American Effort in World War II, Indians played “a vital role as media figures designed to promote the war effort.” This role “developed from a conscious effort on the part of the Indian Bureau, the media, and politicians. The hard-earned reputation of the Indian as self-sacrificing, hard-working, and patriotic implied that the Indian Bureau had successfully transformed reservation Indians into citizens capable of merging into mainstream society.” But there were contradictory tensions in the images and discourse that presented Indians as at once assimilated and exotic.

There is no question, however, that many Native Americans who enlisted or were drafted genuinely felt part of their country—perhaps for the first time—and its mission to defeat the Axis powers. This was likely because their contributions were embraced (as were those of many other previously despised ethnic groups) as part of the fight for freedom. Native American enrollments in the military service went from 7,500 in 1942 to 24,500 in 1945, exclusive of officers. Another 20,000 off-reservation Indians worked at war-related jobs—one of the highest percentages of any ethnic group.

New Mexico Indians from all nineteen pueblos, as well as Apaches and Navajos, served in every branch of the armed services, as well as in defense factories. Men served as “deep-sea divers, paratroopers, aerial gunners, medics, and radio operators.” About 300,000 women served in the military during World War II. Out of the 61,000 women on military duty in the month Eva enlisted, some 800 Native women served as WACs or WAVEs [Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service], and hundreds of others worked in hospitals and defense factories around the country. Ironically, the approximate numbers of Native women who served might be low because they were typically designated “white” under “military ethnicity parameters.” …

Before she decided to the join the WACs, Eva looked for factory war work in California, which she was apparently not able to obtain. Inspired by her continuing desire for adventure, and looking forward to the many advantages of living and working in a milieu where she might be able to put her artistic talents to patriotic service, she set out with two Taos Pueblo girlfriends, and the blessings of her parents, to start basic training at Fort Devens, in Bedford, Massachusetts, where she was stationed for four weeks, starting on June 7, 1943.

In her study of Native women who served during World War II, Pamela Bennett found that they had little difficulty identifying both with their nation and their tribes. “The terms ‘traditional’ and ‘non-traditional’ held little significance in the broad view because each of them fully embraced who they were as Native women.” Like Eva, many had come from Indian boarding schools, where they got used to long absences from home and were “exposed to strict regulations within the schools [that] helped make their adaptation to the military a relatively easy process.” While patriotism was a “strong factor in their enlistment decision … healthy self-interests, such as the desire to learn new things, meet new people and travel” were also motivations. The women she interviewed “experienced few incidences of sexual harassment or gender discrimination in their service … overwhelmingly the women stated they were treated with respect and their work was appreciated and acknowledged.”

This was certainly true for Eva. The delight she took in her new path can be seen in her cartoon sketches and blithe descriptions of the exhausting physical labor required in hours of marching and calisthenics during basic training, which she entered into her black address book. Viewing these pages, it’s not surprising to discover that Mirabal would be assigned as both a full-time artist (according to Franco, the only full-time designated artist in the WACs) and commissioned to draw a comic strip for the AIR WAC, a nationally distributed newspaper that was published at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Ohio, where Eva spent her three-year tour of duty.

Eva’s first G.I. Gertie cartoon was published in February 1944. According to Bertha P. Dutton’s Pocket Handbook: New Mexico Indians, “She [Eva] was used exclusively for artwork during the war, painting murals for camp buildings and making a weekly cartoon for an air force magazine.” G.I. Gertie was both revolutionary and subversive for its time. This is not just because Gertie was unlike any other WAC female cartoon character, most of whom were created by white men, but also because of the national panic, which at times came close to mass hysteria, over women enlisting and being recruited into the armed forces.

Public fears were related to the belief that military women were undermining gender roles throughout society, losing their femininity, unmanning men, and most likely serving in the armed forces as a cover for prostitution in order to satisfy the sexual needs of military men. One of the strangest rumors that came out of Los Alamos during the war was that the baby boom that occurred there during the war years because of the Manhattan Project was the result of pregnant WACs being sent secretly to Los Alamos to have their children. Robert Nott interviewed a Santa Clara woman who worked on the Manhattan Project, whom he quoted in an obituary he published about her in The Santa Fe New Mexican on March 12, 2018. Floy Agnes Lee had told him that she did “pioneering research on radiation biology and cancer, working as a hematology technician in early 1945,” although she had no idea what the scientists were working on. “Lee described how Manhattan Project officials tried to cover up the activities of the men scientists, doctors, and military veterans at the site, including women, by explaining that Los Alamos was a ‘hideout for pregnant WACs. Santa Fe loved that story and many believed it,’ she said.”

There were numerous syndicated cartoons during World War II that presented women in the service as one of two traditional stereotypes: feather-brained or mannish. In her book Creating G.I. Jane, Leisa Meyer reproduced several such cartoon images, which were intended to reassure men that women in the armed forces were no threat to them in any way. A WAC goes to a movie theater and asks for “four soldiers, please” at the ticket booth. A WAC shows her engagement ring to a fellow WAC, telling her, “One confirmed—two probables!” A WAC and an army man on a date sit on opposite sides of a couch. The WAC asks, “Can’t you forget I’m a first-class private?”

In The 10 Cent War: Comic Books, Propaganda, and World War II, Trischa Goodnow and James J. Kimble take a more benign view of these stereotypes, at least as they were deployed in comic books, which they believe “might have helped foster tolerance for the newly created women’s corps by using recognized gender stereotypes as contrary evidence to dominant social complaints about women’s military service.” Comics “reframed gender norms to depict feminine stereotypes as strengths, rather than weaknesses in military service.” But they admit that while “women were encouraged to expand their self-expectations and dreams,” it was only to be “for the duration” of the war. At the end of the war, all conceivable social and cultural forces were brought to bear to get women back to their domestic duties.

The enabling legislation for the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) was passed on May 14, 1942. The army refused to have a service over which they did not have full control, so women, as auxiliaries, were denied equal rank, pay, and benefits, such as tuition to attend college after they finished their tour of duty. The women in charge of the WAAC demanded better—full membership in the army—and they got their way when Congress passed a bill on July 1, 1943, that established the Women’s Army Corps (WAC), providing women the same rights (except for fighting on the battlefield) as men.

However, this change in status did not affect most media representations of WACs in the least—if anything it created a deeper need to deny women’s intelligence and equality. The most famous cartoon and comic book WAC was Winnie the WAC, who also became a pinup girl known as the Flaming Bomb. White and sexy, she sits on the lap of a patient in a dental office and tells the dentist she is doing it to cheer him up. She brings bags of clothes back to her dormitory after a shopping spree, complaining that the WACs were “too uniform.” She poses as a newspaper journalist who doesn’t need a notepad for her articles because she has “lots of room in my head.” What is most outrageous about this portrayal is that the model for Winnie was the brilliant Private Althea Semanchik, who had taken a course in higher mathematics under Army supervision and was assigned to the instrument section of the Fuge Chronograph Department in Aberdeen, Maryland. There, she worked on computing the firing ranges and hitting power of shells. Winnie’s creator, Corporal Vic Herman, won an award for his strip in 1945. Both he and Semanchik got a three-day pass to go to New York City to be feted at the Pen and Pencil Club.

In dramatic contrast, Mirabal’s Gertie uses her wit to undermine army rules. In one first strip, published in February 1944, she greets her superior as an equal, as though difference in rank doesn’t count; in another, she writes a letter where she lies about her grandmother’s death in order to obtain a leave. It is sad to note that while there are scores of images of mostly silly cartoon women WACs and WAVEs available to historians in books and archives, there would be no knowledge or memory of G.I. Gertie’s publication if Elaine Wagner had not found the AIR WAC newspaper that published Eva’s first strip. It is one of only two strips we have been able to find—the other was cut out of the paper, probably by Eva, and photocopied.

Two years of scouring government and military museums and archives has yielded no other copies of Mirabal’s comic strip. Among the many US Army and Air Force archivists and historians I spoke with, one told me that it was unlikely that the AIR WAC newspaper would have been saved because it was by and for women and thus not seen as having significance. The issue Wagner purchased (the first in which G.I. Gertie appeared) includes substantial coverage of many aspects of the lives and work of WACs at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base. However, it is not surprising that at the time it was considered inconsequential because it was about women.

In addition to her professional accomplishments, Eva’s papers reveal the private side of her life during the war, which paralleled the lives of many women in and out of the armed forces who had male friends and boyfriends abroad, and for whom the possibilities of wounding or death on the battlefield heightened the intensity of romantic bonding and the frequency of early marriage. Eva held on to a small but precious collection of love letters written to her by two men she had met during her time at SFIS, who were now in the armed forces.

The bulk of them are from Private Homer Charlie, a Navajo from Crown Point, New Mexico, who was stationed in Texas in 1941 and eventually sent to a military base in the Panama Canal Zone. He wrote to her frequently over the course of three years, with the intention of one day marrying her when he returned home. His letters reveal not only the intense loneliness many soldiers felt for the women they left behind, but also the great respect he had for her talent as an artist. Before she entered the WACs, he encouraged her to take advantage of an art program she had written to him about in Phoenix that would allow her to take more classes, and he encouraged her to go to college, regretting that he had only finished high school.

On December 11, 1941, Homer spoke yearningly of wishing to see her before being sent abroad: “Just remember what I’ve told you, that I always did love you, and will be thinking of you forever and ever. I wish you could too. We’ve had a swell time together you know. You’ve got a good future ahead of you, keep it up. I hope you succeed. Think of us Soldiers.” Eva apparently reciprocated his feelings, to judge from his comments about one of her letters. Among other things, Homer provided an interesting glimpse of the dating life of young Indian teenagers at the SFIS and ABQIS. On February 3, 1942, he wrote to her at Fort Devens from the Canal Zone: “Them were the days when I used to race up and down between Albuquerque and Santa Fe. You know why don’t you? Just to see you every weekend and sometimes during the week.” He told her he had to get back to “Bessie,” but that there was no need for her to be jealous because “she” was not a girlfriend but the name of his gun. “When I think of you I’m not afraid anymore, & so I’m fighting for the love of you. Will you marry me and share my happiness until the dooms day comes?”

Whatever Eva felt for Homer, he was not the only soldier who hoped to marry her after the war. Sgt. J.L. Martyn, 479th Bomber Squad, Fort Myers, Florida, wrote on October 5, 1942, “I may sound crazy but I have loved you since the time I went around with you. Will you marry me? I mean it sincerely. I’ll prove to you that I really meant all I said & if you’ll accept me I’ll do my best to keep you happy.” Eva kept one postcard from the man whom she would marry in 1950. She had known Manuel Gomez since they were children in Taos Pueblo. Gomez was sergeant second class at the time he wrote a casual postcard to her on May 10, 1942 or 1943. He said that he thought he would drop her a card because he was thinking of her. “Be glad to hear from you.” But Eva was set on a mission throughout the war and for five years afterward, when she gave her full attention to advancing her career as a nationally recognized artist—which, of course, she already was even before she entered the army.

Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, 1943–1945

When Eva moved to Wright-Patterson Air Force Base (WPAFB) in August 1943, she entered a world that was nothing like any she had experienced before. She had traveled to big cities as a Girl Scout and received basic training at Fort Devens, a major military facility in central Massachusetts. But Wright-Patterson was entirely different in size and military importance. When Eva moved to Wright Field in 1943 (Wright and Patterson air fields merged in 1948), it had just been designated the Air Services Command Headquarters for the US Air Force. At the beginning of the war, the United States had a very small air force. When Eva arrived, there were forty buildings at Wright Field; by 1944, more than three hundred buildings had taken over an area of 2,064 acres. The federal government provided $300 million for the base to produce 5,500 warplanes. By the end of World War II, WPAFB served the needs of the US Air Force around the world.

Wright Field workers repaired damaged planes and worked on air safety and weapons. By 1944, some 50,000 employees lived and/or worked there. Civilian employees peaked at 19,433 in March 1943, half of them women, who worked alongside men as tug and truck drivers, in warehouses, and as storekeepers. The base also had the amenities to provide a social life for enlisted men and women, which included musical performances, dining, and dancing. It was a cosmopolitan place, where Eva encountered people from many walks of life, class backgrounds, ethnicities, and cultures. In effect, Eva was working in a city that had three hospitals, dormitories for three hundred WACs, thousands of servicemen, several large facilities for building new planes, and maintenance sheds and repair shops for repairing them.

Eva was given her own small studio space at headquarters by her commanding officer so that she could continue her own painting, but the demands of her job seemed not to allow her much time for this. (I could find very few paintings from her time at Wright.) Mirabal’s public fame grew exponentially from the publication of her G.I. Gertie strip, as she was very likely the first Native woman to publish her own cartoon. But she was also touted for the extraordinary murals she worked on, both as an assistant for Corporal Stuyvesant Van Veen’s monumental Bridge of Wings, which still exists in the building that housed the headquarters of WPAFB, as well as in her own right, when she was given a commission in October 1944 to paint an original design for a mural celebrating an Air Power show in the Buhl Planetarium, located in Pittsburgh.

On August 31, 1943, before Eva had even begun the work that brought her local and national magazine coverage, she was interviewed by the base radio station about her career as an artist. She told the interviewer that she had made art her career up until the time she joined the WAC, and that she had always participated in the dances at her pueblo. She painted “episodes from the lives of Indians, their ceremonies and watercolor landscapes. Most of these have been done on order from collectors who visited my studio in Taos. After the war I intend to illustrate a book on Indian legends from the stories told to me by my grandmother. She is in her 90s now. This book will also contain illustrations of famous buffalo hunts and other exciting adventures in Indian legend which my grandfather related to me.” When asked why she joined the WACs, Eva replied that two of her friends and she “decided we wanted to help the war effort so we joined at once.” Her interviewer, who obviously knew nothing about Pueblo villages, seemed anxious to establish that her ultimate goal was to settle down “in a little home in the west with a little white fence, flowers, and …” Mirabal cut him off: “If you’re talking about marriage, Corporal, that’s out for the duration. We’ve got a war to win—remember?”

—

Lois Rudnick is a retired professor of American studies who has written and edited ten books, mostly about New Mexico arts and culture. She also teaches courses for the Renesan Institute for Lifelong Learning.

Jonathan Warm Day Coming is an illustrator, painter, and children’s book writer who lives in Taos Pueblo. He is the author of Taos Pueblo Painted Stories.