I Change into My Levi’s That I Bought With Last Year’s Potato Harvest Money

Querencia and New Mexico’s Manito Diaspora

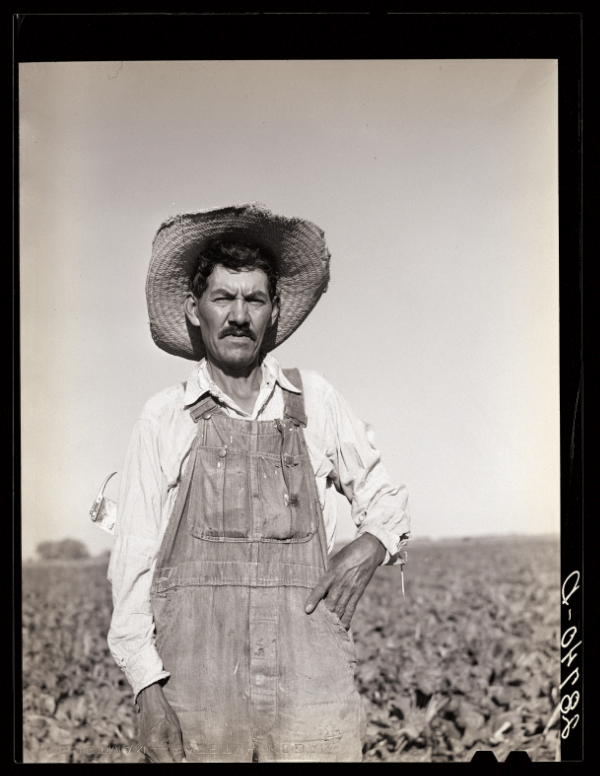

Loading wagon with sugar beets, Colorado, 1938. Photograph by Jack Allison. Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Black-and-White Negatives. LC-USF34-015800-E.

Loading wagon with sugar beets, Colorado, 1938. Photograph by Jack Allison. Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Black-and-White Negatives. LC-USF34-015800-E.

By Jim O’Donnell

Rosie left for Colorado when she was 6 months old. Her family travelled by covered wagon, crossing the mountains and making their way north. The year was 1921. José Delores Cordova, Rosie’s father and a recently returned veteran of the First World War, simply couldn’t make ends meet farming and ranching the high desert plateau north of Taos, New Mexico. He and his wife, Maria Refugio “Ruth” Martínez, had gotten wind of decent-paying jobs in the sugar beet fields outside of Fort Collins, Colorado, run by the Great Western Sugar Company, and so they left their ancestral village of Cerro and joined hundreds of other Hispanic New Mexico families—los Manitos—migrating north for better economic opportunities.

The northeast Colorado sugar beet industry of the early twentieth century has been described as an empire. Beet fields sprawled across thousands of acres surrounding communities such as Greeley, Eaton, Loveland, and Fort Collins. Workers and their families poured in from all over the country and beyond. In Fort Collins, the neighborhoods of Andersonville and Buckingham filled with immigrants from Russia, Germany, and Eastern Europe. New Mexicans settled the Alta Vista neighborhood.

José Cordova had been to Colorado for work before—probably several times, as was common for the Manitos of New Mexico’s mountain villages. The 1920 United States Census lists Cordova as living in both Cerro, New Mexico, and Windsor, Colorado. For a time, he herded sheep around Meeker, Colorado. Yet for José, it didn’t make sense to be apart from his family, and he was determined to bring them with him. Steady work in the sugar beet fields gave him that opportunity. It was in Alta Vista that José and Ruth Cordova built an adobe home on Martínez Street sometime between 1920 and 1922, when Rosie was just a little one.

“My brother and I helped mix the mud with the sand and the straw. We’d take off our shoes, roll up our coveralls and just get in there and mixed it all up,” Rosie said in an interview before her death in 2007. “My father would make up the adobes, leave them to dry for one or two days. He kept turning them until they’d dry evenly then he’d put them in a pile until he had enough to build another wall.”

José and Ruth raised ten children in that adobe house. The boys slept in the attic, the girls below. Before long, José’s parents Juan Miguel and Eleonora Cordova joined José and Ruth in Alta Vista, creating a new home just across the intersection. José’s brother, Manuel Ruperto Cordova and his wife, Lilly, settled in across the street.

“This is my family,” says Rosie’s granddaughter Ashley Cordova, my wife’s cousin. “We’ve been in Fort Collins for eight generations. Over 100 years. The older I get, the more infatuated I get with our family story. And I want to preserve that legacy.”

Manito. Mano.

I once met a man named Arsenio. He was 94 years old at the time. He was from the village of Peñasco, south of Taos. When I told him that I was born and raised in Pueblo, Colorado, he launched into a string of stories about his life as a Manito, working in the train yard at the sprawling Rockefeller-owned Colorado Fuel and Iron Company steel mill. I told him my grandfather worked there from the 1930s into the 1970s and, as the crazy world works, it turned out my grandfather had been Arsenio’s boss. This was the first time I’d heard the term “Manito.” According to Arsenio, the term meant “hand,” as in the calloused hands of the hard-working migrant laborer.

Mano. Manito. The name more likely comes from the term of kinship and endearment rooted in the Spanish word for brother. Hermano. It’s an old term. Some early collectors of folklore and oral histories feel that the word manito may have originally been a somewhat pejorative label for the “mixed-blood” Hispanos of El Norte. Regardless, by the late 1800s, “mano” and “Manito” were used in terms of kinship, brotherhood, sisterhood, care, and shared identity. The name Manito is used to this day.

And yet mano in terms of hand is probably not far off in other respects. It was the hands of these New Mexico families that harvested the beets of Colorado, built the highways, dug the mines of the West, and herded the sheep of Wyoming. At home, it was the manos that shaped the adobes, fixed the roof, harvested the corn and chiles, and built new lives far from home.

Levi Romero, poet and associate professor in Chicana and Chicano studies at the University of New Mexico, writes in an introductory brochure for the Millicent Rogers Museum’s exhibition about the Manitos that “Not every New Mexican calls themselves Manito. Some New Mexicans prefer to be called Chicano. Others prefer Hispanic or Latino. Some people just like to be called New Mexican. Here, we use the term ‘manito’ because for us it means family and community.”

Now, a number of researchers—many Manitos themselves—are working to preserve the legacy of this chapter of the American experience.

Summers En Los Campos

Savannah P. Rodríguez

Dedicado a mi Tío Leroy

Summer is here y ya nos vamos a Colorado

Tío Ezequiel, Tía Sofía and the rest of the crew están esperando

I change into my Levi’s that I bought with last year’s potato harvest money

Grab my big hat and long sleeves

Estoy listo

We left home when school was finished

When the air was hot and dry

When there was no work and Welfare ran out

So we all hopped into the back of the troca and we were on our way

I was 6 years old the first time I went to the fields

Too little to hold the hoe, so I watched

Learned

Understood what work was and the value of feria

I walked up and down the rows

Up to all the sweaty trabajadores

Chicanos from all over the place

And offered ’em Daisy cups of water

For one penny a pop

Back home there was much time to practice in our gardens

I looked forward to the next job, next town, next field

During the harvest, we went to Monte Vista

Filled a thousand sacks of papas a day

For fifty bucks a week

I’d clean acequias on the weekends for fifty cents an hour

For pencils and paper and pantalones for my siblings

Sometimes on my day off, I’d take the bus into town

Fort Garland to Alamosa

Walked half a mile to the swimming pool

Bought a burger and a song on the jukebox

For years after I graduated high school and left home to California,

Soñé de los campos

Y los extrañé

Picking peaches allí en Grand Junction

String beans in La Junta

Boxes of watermelon and cantaloupe

Buckets of onions, beets, and lettuce

Farmer’s tan

Knees and hands stained with dirt

I dreamt of summers

En los campos

For centuries, Hispanos from the mountain villages of El Norte have had to travel in order to survive. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, ciboleros crossed la sierra, the Sangre de Cristo mountain range, to hunt with their Comanche allies on the Llano Estacado, the great Staked Plain stretching from the foothills into present-day Texas and Oklahoma. People moved regularly up and down the trade routes into Mexico and, later, between the trade centers of Taos and Santa Fe to the American frontier and the commercial center of St. Louis.

It was with the United States invasion and annexation of what we now call the American Southwest that economic and social conditions in the villages of Northern New Mexico morphed so dramatically that large-scale migration and permanent resettlement of Hispano families far from home took place.

In 1848, the United States of America and Mexico signed the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, officially ending the American war on Mexico and codifying the American takeover of Texas, New Mexico, and most of present-day Arizona and California. New Mexicans of the agriculture-based villages of Northern New Mexico suddenly found themselves on the other side of the border in a country with an entirely different legal and economic system. “This reality has had a significant impact on the day-to-day experiences of Nuevomexicanos,” writes Dr. Trisha Venisa-Alicia Martínez of University of New Mexico – Taos, an expert on New Mexico’s migrant workers and families and author of Living the Manito Trail: Maintaining Self, Community, and Culture. “Communal lands where they once grazed their livestock and gathered wood were seized [by Americans] and no longer accessible. Many communities were banished from their property and displaced from their livelihood.”

Dr. Martínez, grandchild of Manitos who settled in Wyoming, recently returned to her ancestral village of Valdez in Taos County to raise her children, give back, and work the land of her ancestors. She is furthering her research and continuing to document the history of Manitos as research scholar for the Following the Manito Trail ethnographic project, and as migrations manager for the Manitos Community Memory Project.

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo assured New Mexicans that their communally held lands would be protected by the United States. However, as with promises made to Native Americans, these assurances were rarely kept. New Mexico’s agricultural communities were marginalized and saw their land-based economies undermined.

“In my own research,” says Dr. Vanessa Fonseca-Chávez, associate professor of English and associate dean of diversity, equity, and inclusion at Arizona State University, “I have noted that modernization processes in Northern New Mexico prompted migration for many Manitos. Following the Mexican-American War of 1848, Nuevomexicanos became wage laborers in a wage-based economy—meaning that they were expected to earn money to pay for goods, services, etc. As land-based peoples, they encountered a system brought forth by U.S. colonization that was largely unfamiliar to Nuevomexicanos. We often note that Manitos migrated because they had to—and primarily to find work elsewhere.”

The latter half of the nineteenth century saw Manitos spreading north to work the coal mines of southern Colorado, the steel mill in Pueblo, the sugar beet fields of the Wyoming-Colorado borderlands, and as sheepherders in the mountains of Wyoming. Manitos also took jobs in stores, with construction crews, and at meat-packing plants. Later, more Manitos were pulled to shipyards and aircraft factories during the world wars. New Mexican migrants extended their reach into Texas, Arizona, and Gold Rush-era California as well.

American business also drove the migration north. Many companies seeking cheap labor sent recruiters to the villages of El Norte, promising housing, good pay, and decent working conditions. It wasn’t just the sugar beet industry. The mines, factories, and railroads found in the Hispanos of Northern New Mexico a land-based people thrust into an unfamiliar wage economy to which they were forced to adapt.

It is unclear how many New Mexicans left home. “Because the Census data only accounts for every ten years, its fairly easy to track where people were in 1910, 1920, 1930, etc.,” says Dr. Fonseca-Chávez. “But we don’t currently have the data to know how many people left in any given year or over a number of years.” Fonseca-Chávez and a colleague, Dr. Eric Nystrom, are working on an estimate for migrant numbers by interpreting the Census data. That work is in its early stages.

People also went back and forth, making an exact count difficult, if not impossible. An estimated 250 to 300 men from the village of Chimayó averaged five to six months away from home each year in the 1930s. Even before the Great Depression, as many as 85 percent of the men from Tierra Azul were away working in sheep and lumber camps. At first, Manitos who migrated for work tended to do so only seasonally. They would leave for several months in the summer and return for the winter. At times, working men were gone for years at a time. Migration was key to survival.

“My paternal grandparents are from Valdez, both of them,” says Dr. Martínez. “They knew each other’s families and they met in Wyoming. As of work—options were limited, so people would go out of state. My grandfather left after he got out of the Army. People around here would go—and pick papas, they would go take care of sheep, they would work the mines. … Somebody’d say there was work somewhere, and a lot of the people from one area, they would go together, live together in the same area to help each other out. And a lot of the time, the ladies would just stay here, taking care of the family, the animals, and the ranchitos. The men would come back and bring money in, just keeping their land, keeping the way going.”

“The people left behind had it rough,” says Doug Cordova, nephew of Rosie Cordova and the family historian. “The women had to do everything. They had lives of their own doing the day-to-day on the farm.” Doug speculates that the Penitentes, a religious order unique to Northern New Mexico and southern Colorado, helped support the women and children left behind.

With most of the men of the villages gone, the women crossed traditional gender norms by working in the fields, building the houses, taking an active role in faith and spirituality, and practicing medicine, points out Dr. Martínez.

“The women became the culture-bearers,” she says. “We have a legacy of powerful women in our communities. They had to be. They raised the children; they built the houses. But it didn’t come without loss. The loss of men meant loss of certain experiences. Yet this reality inspired the strength of our matrilineal heritage and families.”

“The other thing,” says Doug Cordova, “is that the men were often gone so long that the women who stayed behind had other relationships, so there were a lot of out-of-wedlock kids, half-brothers and sisters.” It made sense as, at times, husbands were gone for upwards of ten to twenty years, often starting new families where they lived. All this, Cordova guesses, may have contributed to the deep intertwining of relations he sees in his own family.

When the Great Western Sugar Company offered to move whole families and even supply housing, the choice for many New Mexicans was clear. Family mattered. It only made sense to José and Ruth Cordova to keep their nuclear family together and move permanently to Colorado.

Borders, much like the concept of race, are a social construct. A social construct does not have inherent, “real” meaning. Social constructs are created by people, and the only meaning they have is the meaning given to them by people. Borders don’t actually exist in physical reality; they are constructed in our minds. Borders are imaginary and arbitrary, and yet they play a profound and deeply problematic role in our everyday experience. Just because a border is named doesn’t mean that it instantly alters existing ties and realities on the ground.

The idea and implementation of borders is a relatively new concept on the human timeline. Migration is part of the human condition. Simply put, humans have always moved across the landscape for fresh opportunities.

At the same time that New Mexico’s Manitos were spreading throughout the West for work, tens of thousands of Mexican nationals likewise came north seeking fresh opportunities. Mexican workers 100 years ago, much like today, were seen as both undesired yet highly valuable as exploitable workers. Mexican migrants were on the receiving end of an enormous amount of racism, and that reality impacted Manitos.

According to Dr. Martínez, “it is important to acknowledge the conflation of Mexicans, Mexican-Americans, and Manitos, particularly in terms of how they have been perceived as one culture and community.” For much of white America, there was no difference between Mexicans and New Mexicans. While the Manitos were American citizens, their rights were frequently curtailed in their new communities as they were lumped in with non-citizen Mexicans because of the color of their skin.

“‘No Dogs and No Mexicans Allowed’ was the sign on the door of the store,” Vi Esparza recalls. “They were everywhere those signs. All over Fort Collins.”

Esparza, Rosie’s sister, remembers her father José Cordova speaking only Spanish at home while sticking to English in public. “He paid his bills at the end of every month. He showed respect and demanded respect. He wanted to work harder than everyone else to prove that we were equal, and he told us: ‘Don’t think you’re better, but certainly don’t ever think that you’re worse.’”

José held down three jobs. He worked in the sugar beet factory in the day and topped beets all night. Depending on the season, the family harvested at farms across the area. Cucumbers, cherries, peas, pumpkins. Esparza recalls being pulled out of school to harvest potatoes. Their father dug up the roots and she and her sisters followed behind shaking the spuds from the vines.

“It was very, very difficult. We were calloused and sunburned and tired. Even the other New Mexicans looked down on us for a while. But I guess, when you work hard in life, you appreciate it when you’re older.”

The Fathers

by Dr. Patricia Perea

For George Perea and Jacobo Perea

These are the fathers I know. Like twins.

Inseparable as night from day.

They were always following each other. Often

they lived in the twilight—that fine

line when the light goes from lavender to amethyst—

when sapphire hovers just above the straight

horizon of the southern plains.

I traveled miles with them—miles between Lubbock and Amarillo,

Friona and Canyon, Clovis and El Paso,

Albuquerque and Vado.

Between us, there were piñon shells, Marlboro Reds,

whiskey and Allsup’s chimichangas. And on the AM radio rancheras

crossed paths with honkytonks on the dial.

My fathers had secrets I never knew. Secrets held in the red

rocks of Dilia houses, the loud shipyards of Oakland,

the cotton fields of Texas, and the dry sands of the Chihuahua desert.

At Christmas and birthdays, I got dolls and doll furniture,

rabbit fur coats and headbands; I loved them all;

used them until they fell apart in my hands.

But what I really wanted, I never said.

I wanted to be like them.

I wanted to take hits at the punching bag in the barn,

learn to shoot combos at the pool table,

brush down the horses, and maybe practice a pretend spar in the backyard.

I wanted to be between them, sharing everything, telling jokes

and sometimes crying over the lost land I had not yet seen.

I wanted to know the stories behind their dark eyes,

or the reasons for the slight breaks in their laughs.

I want to know why my dad held my grandpa so close and pushed

all the rest of us

so far away.

The Manitos weren’t always welcome in their new communities. There was the overt racism they frequently encountered such as the “No Mexicans” signs, and then there was the pervasive marginalization and neglect.

Frequently, white migrant workers had access to better working and living conditions. It was common to see access to voting rights, commerce, and even basic infrastructure curtailed for the New Mexicans.

“Manitos and their Mexicano relatives continue to evolve in a world of borders [that] attempts to limit and define their existence,” writes Dr. Martínez.

“To the Anglos, we’re all Mexicans,” says Nety Arias of Cheyenne, Wyoming, related to Dr. Martínez—and thus the Manitos, much like the Mexicans, were segregated from white people.

In a new paper slated to be published in the fall of 2022, “We Were Always Chicanos, or, We Did it Our Way: Situated Citizenship in the Equality State,” Dr. Fonseca-Chávez takes an in-depth look at how Manitos in Wyoming were not afforded the same rights as their fellow Americans, who were white. As she notes, the New Mexicans—and in particular the women—pushed back. “Chicanas challenged notions of gender and ethnic equality and fairness in Riverton, Wyoming, an unlikely place to uncover historical moments of Chicana activism.”

A number of the individuals she and Levi Romero interviewed for the Following the Manito Trail project pointed out that because they were perceived as Mexicans, many Manitos had difficulty finding housing in white neighborhoods throughout Wyoming. This “almost always led them to ethnic havens on the south side of town. Even though these neighborhoods were connected by cultural and racial heritage, they often were neglected by city and town officials due to existing racist sentiments.”

The women, the Chicanas, were forced to mobilize their communities to get the basic infrastructure services they needed and that white neighborhoods enjoyed. They organized their communities and used their voting power, pushed the municipalities to direct money their way, applied for state and federal grants, and even fought in the courts. In Riverton, Wyoming, these Chicanas, fed up with the waiting and the stalling, took it upon themselves to pave their own streets. In other places they installed sewer lines or drinking water systems. More often than not, the whole community joined together to get the work done.

“Their activism elucidates the extent to which they were keenly aware of their positionality within a state that is overwhelmingly white and one that historically has failed to extend equality and fairness to Chicana/o communities as well as other marginalized populations,” writes Dr. Fonseca-Chávez.

One recurring theme in nearly all Manito family stories is the importance of education. Life for many Manito migrant families was hard, and education was seen as key to getting out of the sugar beet and corn fields.

“Grandma takes pride in her education and ours,” Dr. Martínez says. “Education was a way out of the hard labor of the fields and a way to move ahead.”

The Cordovas of Fort Collins also put a high price on education.

“Grandma Rosie told us, ‘Go to school, get good grades, you won’t want to work like we did,’” says Ashley Cordova. “Education was super important for us.”

In 2017, Fort Collins honored the Cordovas with a new street name and, in October 2021, they planted a Living Legacy Family Tree in Sugar Beet Park, where Ashley’s great grandfather, José Delores, worked. This year, the Cordovas will install a street mural in the Alta Vista neighborhood to honor the sacrifices of their ancestors.

There is an aspen tree in an old sheepherder’s camp alongside Highway 70 in the Sierra Madres of Carbon County, Wyoming. Carved on the tree are the words “Taos” and “Arroyo Seco.”

Wyoming’s forests are covered in tens of thousands of tree carvings known as arborglyphs. Arborglyphs can be both pictures and text cut into the bark of living trees. Most of Wyoming’s arborglyphs were made during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, first by Hispanic New Mexicans, then Mexican, then Basque, and now Peruvian sheepherders.

Videographer and documentarian Adam Herrera and Dr. Troy Lovata of the University of New Mexico have spent the last several years studying these arborglyphs. They hope to construct the cultural histories of Wyoming’s aspen forests and to fill in the historical gaps left by a lack of written and oral histories.

The carving of arborglyphs is a cultural trait of Northern New Mexico communities dating back centuries, and the Manitos brought this practice with them to Wyoming, writes Lovata. “Some arborglyphs are clearly billboard-like in their prominent placement and flamboyant forms. These include stylized signatures, notable dates, and vibrant images that are meant to be easily seen and widely understood as strong statements of ‘I was here’ in the face of the vastness of nature, time and labor.”

Still other glyphs are hidden, Lovata has discovered. These in-jokes, jargon, dichos, and messages are targeted at particular individuals or groups. Some are enigmatic. Some are names of people and places. Some express loneliness or the missing of a loved one. Frequently the glyphs express a deep longing for home, a call for the mountains and valleys of El Norte. “No te olvides, amigos.”

Manitos on the migration trail or Manitos who moved permanently to other states generally sought to preserve their unique culture, holding onto their songs, sayings, poems, foods, and other deep markers of culture.

Dr. Martínez places the New Mexican “Manito Trail” migrations among the assemblage of true diasporas, mass movements of people who retain a collective memory and myth about the homeland and a commitment to the maintenance and continuation of their heritage and culture. “To understand Manitos as a community, historically and today, we must consider their migratory experiences and who they are as part of a larger Manito diaspora,” she writes in Living the Manito Trail. “The link between Manitos and the villages of Northern New Mexico have been pertinent in maintaining cultural values and a sense of ethnic identity in marginalized spaces.”

Dr. Sylvia Rodriguez, University of New Mexico professor emerita, defines querencia as both a physical place or location and the subjective feeling that ties a person or people to that place.

This attachment to place, or a homeland, is fundamental in understanding the Manito diaspora. It is a lived idea that ties Manitos to their homeland and culture and sets them apart as a unique people.

Querencia

by Olivia Romo

The deep profound love I have for my homelands,

My connection to the earth through adobe bricks, communal ditches, and the rural

Traditions of my Nuevomexico

Soy India-Hispana. Proud of Spanish coat-of-arms, Comanche cautiva songs, and

Meso-American seeds, like corn.

These are my raices.

Author and photographer Jim O’Donnell is based in Taos, New Mexico. His work has appeared in Discover, Scientific American, Ensia, Sapiens, BBC Travel, and New Mexico Magazine, among others. Jim is the author of Notes for the Aurora Society and a wide range of short stories. Find him at jimodonnellphotography.com.

The Millicent Rogers Museum in Taos, New Mexico, hosts the exhibition Following the Manito Trail, on view through July 31, 2022. For more information, click here.