Love Pa’ Mi Gente Shine Through Me

The Grit and Realism of Chicano Prison Art

By Jimmy Santiago Baca

There was a time when you would have never caught me in a museum. At most, I had maybe visited a cultural display for el Día de los Muertos at our local community center. I had other things to do besides pay an entrance fee I couldn’t afford. Can you imagine my wife asking me where the groceries for the money she gave were and me saying some stupid thing like, “Ah, yes my dear, well, I visited the museum”? No doubt, she’d throw me out of the house after that reply. Besides, I had grass to cut, screen doors to repair, bathtub drains to unplug, kids to run around—unlike those rich white people who could hire people to do all that. And besides, really, when two-thirds of the planet is starving, and most of it is in coughing death-throes from urban toxins, and you hear of someone buying a painting for a gazillion dollars, you’re like, What? Must be a misprint, no? You tell yourself to hold your sanity in place, No, people do not do this. For a picture of corn fields? Nudes? Picasso’s work looks like someone on meth after three months of no sleep, so it really, I mean really, does make you wonder if you’re one of the billions of inhabitants on this planet trying to meet the bills each month and make sure your kids are safe.

Museums weren’t for me: costly entrance fees, guards trailing me, paintings depicting European cultures, wine and cheese (Tequila? Tacos? How about a little cultural sensitivity?), table fruit, girl looking out a window or in a mirror, widow in a rocking chair knitting by a fire, wheat fields. If my wife knew I’d spent the day staring at these paintings, she’d insist I pay her to watch her looking out the window or in a mirror, which she wouldn’t do, not with that youthful glow gone and too many cups of ice cream and popcorn packed in. But loving each other, we’d survive this mega quarrel and hug and kiss and have sex later and probably laugh it all away.

But times have changed, and I caught the bug. The museum bug. Now, not a month goes by when I don’t sweep my kids and wife into the car and head to the latest exhibition at the Albuquerque Museum in Old Town or the National Hispanic Cultural Center in the South Valley or the Museum of International Folk Art in Santa Fe.

I love these excursions.

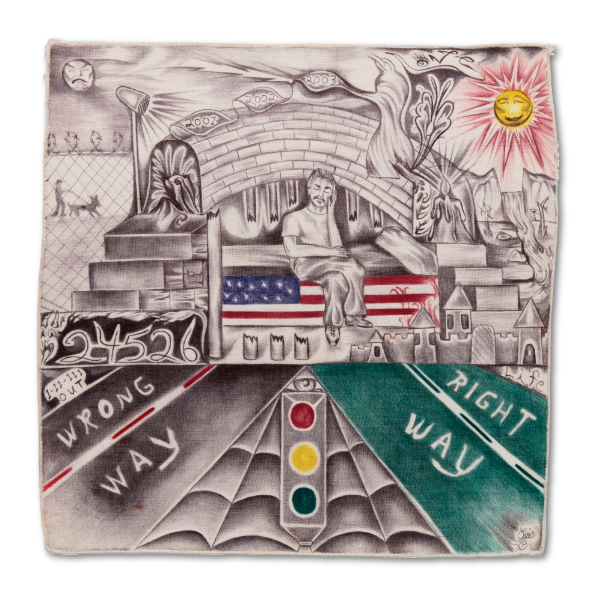

This love affair began, budded, bloomed when museums started showing Chicano art. An important part of the renaissance is Pinto Art, art by men and women in prison. This is the real stuff—grim, vulgar, untamed beauty.

But here’s the catchall—most of the world’s prestigious museums are out scouting the boonies to find these artists and exhibit their work. It’s an enthusiastic time for an exciting phenomenon, with only one setback; whereas thirty years ago you could pick up a Paño or Chicano painting done by a Pinto for say, five thousand, (or sometimes a six-pack depending on the day and mood of el pintor), now you have to sell your firstborn. And that’s good for them, bad for me, Old Empty Pockets Poet (my street label).

Some collectors are paying upwards of a hundred thousand to half a mil or a million a pop. Problem is, no one’s selling because there’s not enough work to go around. It’s like those Walmart Black Friday sales: collectors are pushing and shoving to get in the door first. The smart guys have cornered the market, but at least I can still see the work in museums.

Value. The magisterial skill they reflect, the controlled freedom of the lines, the imaginative colors and merging and blurring any reference you bring to its content, explodes in your mind and spins like it’s a piece of clay on a wheel. The face or car or landscape sometimes is so mesmerizing that I can walk right into it and, for a suspended moment in time, leave my miserably poor life and enjoy, through the Paño art, a happy, fulfilled life. If not fulfilled, then purposeful.

But now to the nitty gritty: The talk about what Chicano art is, for all you trust funders needing to spend your money on a good investment. I’ll tell you what to look for, how to understand it.

Let’s take two of the best museums in the country and their current and upcoming exhibits: the National Hispanic Cultural Center’s exhibition, Into the Hourglass: Paño Arte from the Rudy Padilla Collection, on view until April 14, 2024, and the Museum of International Folk Art’s exhibition, Between the Lines: Prison Art & Advocacy | A Community Conversation which opens August 9, 2024, and runs through April 2025.

A lot of the Chicano art—and Paño arte especially—I’ve seen deal with bad guys/good guys, accidents, injustice, and peril. It redefines the narrative of culture and bias, fearlessly. For so long, we’ve looked at art in museums with an eye-patch on (hell, if James Drake’s work didn’t bring West Texas culture back, we’d still be thinking it was pearl-handled pistols and fourteen-carat spurs).

Paño arte and Chicano painting is returning home with a journey to tell about. Look at the exciting and innovative work of John Paul Granillo, Adam Montoya, Eric Martinez, Nicolas Hererra—those standstills of Indians in ceremonial garb and maudlin, sentimental Hispanic scenes of women weaving and making tortillas in the kitchen are now being (alas!) placed in storage. The feeling that I’ve been mugged is over. I breathe freely, move about, and feel liberated by the new exhibitions.

There is a new vital dynamism of Chicano creativity waking us from our timid voyeurism into the wonderful lashing of waves against reefs that is the cultural renaissance; the Pachuco resurrects, my identity is no longer displayed (or flayed) as a lecherous criminal on canvas, but as a joyous manifestation of engagement with songs, dance, literature, and, in this specific case, painting. Yayyy, I live again, there are artists painting me and my culture as I am! As I wish to be treated, seen, related to. Wow, let the world in! Yes.

Prison art holds a special place in my heart. Artists working under duress and oppression have always produced the volatile work that interests me, and now it seems to have summited public interest, especially for the wealthy, who are rushing, as I mentioned, in droves to museums and galleries to get their rich hands on this work.

Prison art represents the spirit stripped of pretense, the mind at its most acute, and the heart at its most passionate. Do away with the macabre perceptions of the idle, bored artists to portray dumb effigies of who we are—violent, sexually maddened, depraved weirdos. Why anyone would waste their talent painting lies is beyond me, but it does sometimes usher in the deplorable side of the vast breadth of human nature which is inclined towards the cruel and wicked. No, though there is a long road yet ahead, Chicano art has matured, after being long nurtured in silence and isolation, into adulthood.

I speak from experience, having done time for a quarter of a century in some form of contained environment—orphanage, juvy hall, gladiator school at Montessa Park, county jail, and alas, maximum-security prison. It was in these socially sanctioned torture palaces where I first encountered Paño arte and where it first took my breath away. I couldn’t believe the fine detail, the meticulous manner in which portraits were sketched. They came alive and almost spoke, almost gestured to me, almost called me into their world. I noted the symbols and myths, the dreadful needle, and La Llorona in hooded cowl and reaper’s blade.

Prison art is fearless, bends no knee before authority or monarchy of public opinion, and shatters tasteless and timid portrayals. It doesn’t imply, it points with an unblinking stare, it doesn’t shy from historical shames—women raped by gringo vigilantes, police brutality, injustice—no, the Indigenous Chicano takes the stage in Paño arte with dignity and meaning, a purpose that fosters deep thought and new appreciation of an ancient culture and draws from that legacy the richest journey into Self.

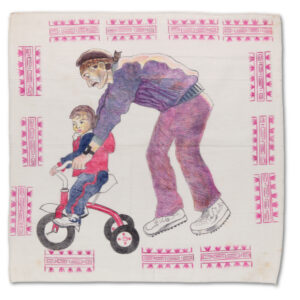

Paño arte, prison art specifically, is a search for meaning and celebration of survival under the direst conditions of repression and brutality, and herein is where the spirit fuses with craft and announces its genius. Rebellion in art is the best art (take Picasso’s Franco period), showcasing our uniqueness, how a prayer on a rosary can suddenly look like a starry night, tattoos become metaphors of love and loyalty, Southwest landscapes and prison landscapes all become grounds for blending the desperate and hopeless with achievement and success, merging the halves into a beautiful whole state of love and endurance that speaks to our experience in the fields, borderlands, prison cells, schools, judicial arenas; every cliché is wrenched apart, the corporate selling points of acceptance and what is mainstream are stomped underfoot and crushed as debris, swept into the gutter and replaced with realism that shows extraordinary grace and control of craft.

The vato loco, la ruca, la curada, Jesús Cristo, y la Virgen de Guadalupe, all take front and center and reach the powerful heights of true conciliation with the viewer in a way that leaves wonder in the bones, appreciation in the mind, a grace that is bestowed and cherished and kept long after leaving the gallery.

We now see things differently.

We now live in a place with fresh eyes; not the idealized, but the communized. I wear sunglasses inside, I button my Pendleton at my collar, my babe wears heavy make-up, I wear my black leather Calcos polished bright, and dude, let me tell you, I got attitude. These are the hallmarks of the Chicano that I am, ages of Indigenous love pa’ mi gente shine through me, and I ain’t taking steps back, pa’delante compa.

The era of trying to please the overseers is over: no more braided little Spanish girls smiling from book covers to please my white audience. Nope, no, no, no. This is barrio land, this Pinto plebe, camaradas in the joint doing time because a racist system loves sacrificing the brightest and most beautiful men and women. This is injustice no more, ya se `cabo, we come now to reflect our mothers’ loves, our familia, our sorrow, and our alegria, no longer are we demonized—because now we are telling the story, we are painting our culture.

This is the new Paño arte and what it fleshes out on handkerchiefs—this is what the Hollywood directors and movie stars and rich stockbrokers and art collectors are tripping over each other trying to buy. The people who have for so long been forced into isolation have come to light, to expose another piece of democracy or lack thereof, to show how people can overcome and thrive and love and destroy each other, how they hurt and what their dreams are, all within the confines of a handkerchief.

What you see of graffiti is a detailed script of place, street-cred lifted to high art form, those hearts and roses and crucifixes are the cultural residue of metaphysical beliefs.

Paño arte is the work of the undesirables, the dispossessed, the disposable human beings, it is clearing the attic cobwebs and opening the boxes and discovering your past, present, and hopes for the future, it’s despair where there is no bottom, no trap door, the telling of a tale of a human being who only has a handkerchief to dwell upon and tell his journey.

Here you will find no white people, you will see judgment from the artist’s point of view, terror from their experience told with a fine-point ink pen or a No. 2 pencil, the shades and dark lines penned with an astute devotion to truth—captive artists working in the most inhumane conditions to render the beauty of their damaged lives.

Sexualized content in its destruction, noir butchery and dripping bloody blades, black ink images of death that haunt, religious piety and assaults on the enemies, renditions of demonic reigns in caressing pastels, mixtures of heaven and hell in grueling combat for the sketcher’s soul, personal histories that disturb the viewer with their disarming sincerity, the gut-stuff of life, the doomed pleas for mercy, a surrendering to God, wherein the artist can no longer endure the piercing agony of his life, martyrdom—here in this Paño where death and life abound, Pintos find their redemption.

The artists sometimes portray themselves as crucified, as tear-dropped faces of dead friends murdered in drive-bys or by police, political raising of fists defying authority, dreams of ancestral victims, generation after generation of family members plunged into the abyss of prison and darkness, all portrayed with love that shines as bright as the sun.

And all of it tells a story of oppression and liberation, love and hate, mercy and mercilessness, all of the bleakness offered in a beautiful Paño for the viewer as another valid face of the real art world that comes from America’s prison industry.

—

Jimmy Santiago Baca is a poet and writer of Chicano descent. While serving a five-year sentence in a maximum-security prison, he learned to read, eventually emerging as a prolific writer and spoken word artist. Baca’s memoir, A Place to Stand, earned him a prestigious international award and was turned into a documentary with the same title.