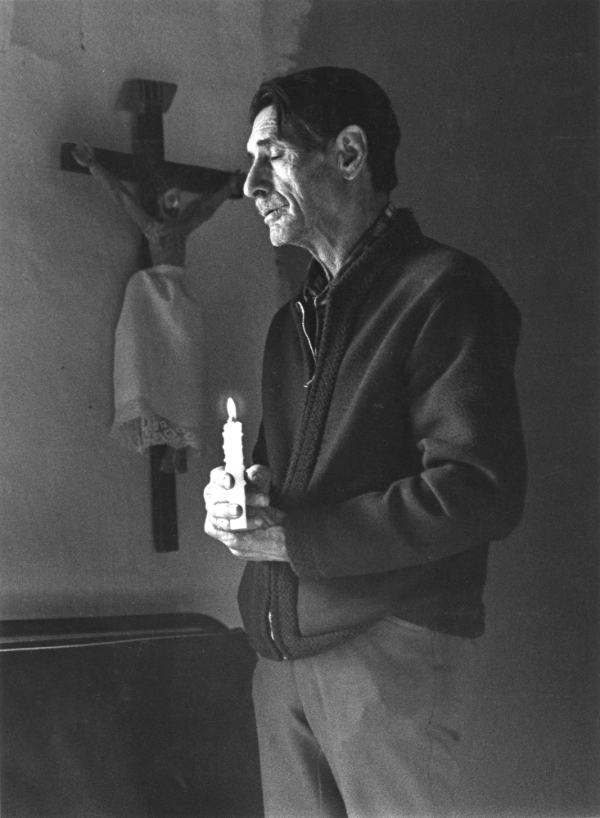

Tinieblas

A Holy Thursday with New Mexico Penitentes

Capilla de Santa Rita, Penitente chapel near Chimayo, New Mexico,

ca. 1955, New Mexico Tourism Bureau, New Mexico Magazine Collection.

Courtesy of the Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA),

HP.2007.20.562.

Capilla de Santa Rita, Penitente chapel near Chimayo, New Mexico,

ca. 1955, New Mexico Tourism Bureau, New Mexico Magazine Collection.

Courtesy of the Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA),

HP.2007.20.562.

By Leeanna Torres

“Dónde estás?” asked Papa over the phone, and after explaining I’d just left the house, headed his way, he quickly insisted, “Pues, para aquí at the capilla!” in our commonly spoken nuevomexicano Spanglish.

The day was the start of the sacred Catholic Triduum that begins at sundown on Holy Thursday and concludes at sundown on Easter Sunday.

“Ya estoy aquí, ven…” Papa explained.

I knew he was talking about the Sánchez capilla. I’d passed the seemingly unassuming building thousands of times on Highway 47 but had never been inside. Ninety-nine percent of the time, the Sánchez family keeps it closed. It was a private chapel, not uncommon in New Mexico. But during Holy Week, it was open, a hand-painted sign out front stating “Capilla San Ramón, Bienvenidos, Welcome.”

I thought of all the places we pass during an ordinary day, the sacredness hidden inside, the solemnity passed over again and again. I thought too about this idea of private capillas—are they about privilege, or are they about individuals creating sacred spaces for themselves, unkept by the laws of a larger religion? Are they perhaps a remnant of a larger standing persecution from the more established Catholic religion? The reasons might be many, or all together and at once, but the only truth was the present moment, and we’d been invited to the Sánchez capilla.

The Sánchez brothers had been inviting Papa to attend their Holy Week events for years, but he’d never been able to attend due to farm work or other commitments. Except for now, this Holy Week, this Holy Thursday.

Native to the Tomé area, the Sánchez brothers had grown up alongside Papa, distant cousins, boys growing up in the deeply Catholic community along the Rio Grande in central New Mexico. And while it was the Immaculate Conception Church (whose building foundation was laid in 1739) which was the formally recognized space of Catholic masses and sacraments, private capillas (and even the remains of a morada) also exist in the community of Tomé.

Papa and Mama raised me Catholic in this Hispanic community; so many of my memories and events often centered around Catholic ceremonies throughout the seasons, including Cuaresma, or Lent. As registered parishioners at the local Catholic iglesia, Papa and I had initially planned to attend the formal Holy Thursday mass. But here we were, at the Sánchez capilla instead.

I wondered what our priest, Father Demkovich, would say if he knew we were here instead of mass. He’d only been the priest in our Tomé community for about a year and was striving to serve as our leader. In that moment I questioned my intentions, but then realized we’d been invited here—and wasn’t there sacredness in invitation as well?

As Papa and I approached the building, questions about this private capilla—its existence, its exclusiveness—calmly disappeared. Approaching its wooden doors and tan-colored adobe walls, I quickly recognized it for what it was—a place of prayer.

I thought of Papa’s aging body, now in his late seventies; I thought of my aging self too, no longer his little girl, now in my forties—but always his first and only daughter. While still actively farming and ranching in our Middle Rio Grande Valley, I recognized the ache in Papa’s walk these days, the way his body swayed in old age.

I also realized the meaning of Holy Thursday for Papa, and how he’d passed it on to me. “I left for Vietnam on Holy Thursday…” was the start of the story he’d told me many, many times, so I knew this holy day always meant something more.

Adjacent to the main entrance door of the capilla, commuter traffic rushed by on a four-lane highway. Diesel trucks and four-door cars all on their way somewhere. It was an unmistakable commotion of rumbling traffic behind us as Papa and I approached the capilla together, just coming to see, but not to stay. Or so we thought.

+

What does it mean to grow up in the Catholic faith? What does it mean to question the church, or not question the church? What does it mean to follow the ceremonies of a specific religion? What does it mean to be devout? And in what ways are traditions and ceremonies allowed to change and transform into a living expression of the people?

Papa grew up and was raised Catholic, as was his father, and his father, and his father. Mama’s familia was Catholic too, and thus both my brother and I were raised within the adobe walls of one of New Mexico’s oldest, and still active, Catholic parishes—La Nuestra Señora de la Immaculada Concepcíon.

Like my father before me, I’d been baptized within the walls of our local parish and remained committed to the faith. But several of my tías, tíos, and primos were no longer Catholic for their own reasons. Why did I stay? What is it that grounded me, tethered me so tightly to the Divine in this Christian tradition?

“Did you go to mass?” Papa asks me often, and most of the time I say yes. But what would we say to each other—come to the capilla instead of the church? I thought of the Penitentes, historically not recognized by the Vatican, and oftentimes reprimanded because only the priests, only the ordained, were allowed to lead.

But when Papa and I went to the capilla, neither of us realized what would meet us there.

+

Papa enters in through the two front doors, open wide. Stepping inside, it’s suddenly cool, damp, dark. Behind the narrow row of wooden pews are fold-out chairs, added for the event’s visitors. Mrs. Padilla is here, along with her esposo; Mr. and Mrs. Romero too. Professor Enrique hands out a paper pamphlet, printed resos inside. “Comó estás?!” he whispers, and we hug, having not seen each other since before the pandemic. This, too, is a fact, so many community members gathered again in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, many still leery, like Erica and her husband sitting along the wall, both still wearing cloth masks over their noses and mouths. A community on the edge of what was separation for so many, many, months, now together again, slowly, cautiously.

“Siéntensen, siéntensen…” invites Mr. J. Sánchez, his hands motioning to empty chairs. His invitation is warm, enduring. Papa and Mr. Sánchez shake hands. Whispers fill the capilla, vecinos talking with vecinos, until the resos start.

Cuatro hermanos de Carñuel, two wearing plaid green and brown work jackets, take their place up front near the altar. Inside, the only light source is dim twilight coming in through the front doors, still open, and thin flickering candlelight from the altar.

With a history as vast and complex as New Mexico’s physical landscape, the myth, mystery, and traditions of the Hispanic Hermanos Penitentes are still alive today. “The Penitentes of New Mexico represent an interesting New Mexican Spanish religious survival,” Dr. J. Manuel Espinosa writes in his 1993 article, “The Origin of the Penitentes of New Mexico: Separating Fact from Fiction,”

This lay Catholic penitential brotherhood… who long have called themselves Los Hermanos de Nuestro Padre Jesús Nazareno, commonly known as the Penitentes, came into existence in New Mexico sometime during the second half of the eighteenth century.

As we are seated in pews along the narrow interior of the capilla, two otherHermanos Penitente standing in the back near the entryway begin the resos with a cadence between prayer and song, voices strong and commanding. There is no sound system, no microphone or speakers; instead, their voices are amplified by adobe walls and the vigas above, low enough to almost reach up and touch.

“Padre nuestro, que estás en el cielo…” begin the Hermanos. Papa’s sitting beside me, reading through the prayer pamphlet handed out at the door, the print of the pamphlet declaring “tinieblas,” but in the ever-darkening capilla, he gives up quickly, folding the thin paper and stashing it in the back pocket of his jeans.

I’d heard of tinieblas, familiar with the worditself—but what is it, really? The paper does not say. Instead, the pamphlet gives only a brief outline of the capilla’s Holy Week events:

INVITATION SEMANA SANTA…

ROSARY… TINIEBLAS… PROCESSION… LENTEN MEAL… ALL WELCOME

(No donations, please).

Within the pamphlet, I am familiar with all except for one—tinieblas. A prayer? An event? A ceremony?

“Help us preserve and experience the rich traditions of Semana Santa at Capilla San Ramón,” states the pamphlet.

As the voices of Los Hermanos speak, a repetitive prayer-answer from the small crowd gathers, I look downwards, eyes drifting along the dirt floor, then over to Papa’s boots, scuffed and worn.

“Padre nuestro, que estás en el cielo…” the repetitive prayers continue. Inside this capilla, full of people, communidad, and as the Hermanos Penitentes recite in my first language, Spanish, I’d like to imagine their resos as old as time itself. Similarly, in the lull of growing darkness and vocal incantation, I’m transported into the teaching by Father Richard Rohr—a globally-recognized Franciscan priest and founder of the Center for Action and Contemplation in Albuquerque—who invites us to realize a “Christ” larger than Jesus, an eternal Christ more powerful and expansive than any human heart can conceive.

I think too of Father Demkovich, our priest just a few miles down the road assigned to the Tomé Catholic parish, preparing for the mass, a different prayer and ceremony than this.

In this capilla with the Hermanos, the place of prayer feels rogue, rebellious, and deeply grounded in the people, of the people, for the people. This here and now feels different than any mass I’ve ever attended. This capilla, these Penitentes aren’t ruled by the Vatican or any Archbishop. It’s its own kind of gathering, a ceremony as old as New Mexico, or at least I’d like to imagine it this way.

“The Penitentes, a private Catholic brotherhood, is wholly unique to Northern New Mexico and southern Colorado,” Sol Traverso wrote in Taos News in 2022. “While its date of origin has been debated, they have been in the area for hundreds of years and are centered around community and penance, a Catholic sacrament involving the confession of sin, self-punishment and forgiveness.”

What is prayer? What forms does it take? I thought of the prayers my parents taught me, the ones Nana recited, and the many said by the numerous priests of my childhood. How was this current time of tinieblaswithin this capilla similar? How was it different?

Light wanes inside. I can hardly see Papa’s shadow next to me now. Resos y mas resos. Between breath and word, I imagine the Hermanos praying for the suffering of the whole world. Some of us seated repeat the prayers in cadence with the Hermanos, but others are silent, the sacredness of adobe walls already settled into their bones. We are just ordinary people, reciting prayers passed down through generations as the light inside the capilla darkens.

We entered through the wooden doors as twilight was settling into evening. And now quietly, almost unnoticeably, the Hermanos close the two main doors, enclosing us all inside, the dim flicker of candlelight at the altar keeping our attention as the voices of the Penitentes continue their prayers.

The rituals of Semana Santa have been present in my life since childhood, yet this is different. How many Catholic masses had I attended in my forty-plus years? I’d been to cathedrals and basilicas in other cities too. But here in this small adobe capilla, among vecinos and familia, my body tenses. Still seated, I try focusing on the voices, on the physical presence of Papa beside me.

Then slowly, almost imperceptibly, the Hermanos begin blowing out the twelve candles at the front altar, one by one. Their voices in prayer do not stop; their cadence continues, the only thing grounding us as the darkness inside begins to squeeze, engulf, smother. Before I realize, it’s pitch dark inside. Resos y mas resos. I can see nothing now. Absolutely nothing. A complete darkness. My eyes struggle. I can hear people shifting in the pews. Los Hermanos are still praying, and I struggle to hear as their voices lower. Somehow, I can’t move; my body is suddenly paralyzed within the darkness.

I struggle to sense the people around me. Wasn’t I just sitting inside adobe walls with my vecinos? Where are they? I can’t see them, can’t sense them, and in this darkness, I am sharply alone, clinging to the cadence of a prayer, song, and voices I no longer recognize or sense as familiar. Something in me wants to reach over, to feel Papa still sitting next to me, but I’m paralyzed in this darkness, more fearful than even now I care to admit. Why? What’s happening?

My eyes still struggling, looking for light, any light. But nothing. Only the voices of the Hermanos. They are plunging us into the darkness. They are plunging me into darkness.

Then the songs, the voices, the prayers—all of it stops. In a capilla full of people, it’s only silence and darkness. I’m here, waiting for what will come next, paralyzed in fear. Why? What’s happening? Where has my logical mind gone? I wait for it to pass. It does not pass. There is only deeper darkness.

It is silent for longer than I care to admit. I’m paralyzed for longer than I care to admit.

Then, I hear what sounds like metal snapping, cracking, splintering. It’s sudden and terrifying, and still, there is only darkness. I try opening my eyes wider, grasping for light, but there is nothing. More unfamiliar sounds, what I’d describe now as chains falling on wood. Clanging and dragging in the darkness.

Still unable to move, I try feeling my body, time itself suddenly gone.

What is darkness? What steepness or gravity presses on both your senses and your soul when you least expect it?

The sounds stop. There is no light. Papa is not beside me. No songs, not even prayers. Only darkness.

Then one candle is lit, a single yellow flame breaking the darkness. One of the Hermanos begins to sing an alabado, low and grounding.

In my daily life, I seek joy as much as peace, but what I found in the participation, the invitation, to las tinieblas that evening at the San Ramón Capilla was something different than my common Catholic upbringing. Even now, a year later, I think about what we witnessed and experienced. Historians and estorias tell me there used to be Penitentes in my home region of Tomé as early as the 1800s. As a child I’d heard the mythologized, and often exaggerated stories of New Mexican Penitentes. But really, I did not know what the Penitentes were about and what they illuminated about the Catholic faith.

Truth be told, I did not experience what Willa Cather’s novel Death Comes for the Archbishop describes as, “the bloody rites of the Penitentes.” Instead, what was revealed to me was a practice of much deeper gravity. Not a bloodied dramatization, but an event grounded in unabashed and unapologetic validity. It was a lesson I had not learned in my many years as a traditional New Mexican Catholic growing up in and among the formal church.

To experience a New Mexican Penitente ceremony is not to describe it. To experience a prayer is not the same as to say it. And I thought of the invitation Papa had received, and how he and I were welcomed into a space not recognized by the Archdiocese of our upbringing.

+

“How would you describe tinieblas?” I ask a Nuevomexicana friend one morning on an outside patio restaurant. There is a long pause, deep thought on her part before she answers, her hand holding a cup of coffee. I watch steam rise from her cup as she thinks about this seemingly simple question.

Her pause is longer than I expect. It’s in that moment—many weeks after the actual tinieblasevent at the capilla—that I realize many of our nuevomexicano traditions are just this: hard to define, difficult to describe, impossible to ever fully explain. Instead, their essence is cupped gently in the liminal space between our essence, our identity, and our deepest knowing.

How to explain the importance of a New Mexican matanza, a velorio for your Nana? How to explain or describe New Mexican tinieblas?

Then came my friend’s answer. “It’s a practice,” she replied with deep conviction. “It’s a practice, but one where you say to yourself, ‘I don’t even fully understand what’s happening right now, but I accept it as a part of myself, a part of my community, a part of my querencia.’”

Las Tinieblas, more than a ritual, more than a ceremony or event.

Las Tinieblas, an outward expression, a practice. This reso, devout individuals—Penitentes—actively practicing what my amigo (and UNM scholar emeritus) Professor Enrique Lamadrid explains as “una visita.” And these men pray not as performance, but out of expression and season and faith.

Tinieblas is Spanish for the Tenebrae service that represents the darkness and chaos following the Crucifixion of Christ. But more than this.

Las Tinieblas, the ritual of “the darkening,” takes place inside a morada on the evening of Holy Thursday. But more than this.

My friend puts into words what I’d been trying to define for myself about what happened that evening at the capilla. When prayers move you, when they create a physical reaction, and yet you cannot define nor fully understand it. Nor do you necessarily want to understand it. This is the power of practices that reflect the terrain and culture we come from here in Nuevo Mexico.

The complex history and current-day continuation of evolved practices of our Nuevo Mexico cannot be fully understood, rationally defined, or even accurately described. That evening with the tinieblas, I came to experience darkness with a gravity my soul had not yet grasped. My entire life, catechism classes and Catholic mass services had tried to explain the plunge into Christ’s passion. Somehow, they’d all fallen short. But now, at a rogue capilla within a Holy Week service led by Penitentes, I’d been plunged into a strange and sudden re-translation of holiness, ceremony, and reso. This is the power of practices reflecting the terrain and culture of Nuevo Mexico.

+

One does not have to be Catholic to experience tinieblas; in fact, I’d dare say my Catholic upbringing had less to do with what I experienced that Holy Thursday evening than I can explain. Because suffering, turmoil, and what any individual might name as their deepest darkness is a brutal yet universal truth for all humans. Although tinieblas was centered and grounded in the passion of a universal Christ, more importantly it seemed to reveal what it means to be invited as both human and divine. An inevitable journey into the darkness.

The community was just coming out of the COVID-19 pandemic when I experienced tinieblas at Capilla San Ramón. COVID-19 had been a kind of darkness for so many. And cancer in the community. And poverty in our country, despite such wealth. Political division in our nation. War in the world. Seemingly endless darkness in so many ways. And yet, a single candle was lit by a Hermano Penitente, to break the darkness, to reveal the light.

That night, Papa and I exited through windowless wooden doors, the sun long set, our limbs shaky and unsettled. It was only the start of our holy days. Before I could look to Papa, ask him if he’d experienced any of what I had, Mr. Sánchez warmly spoke, “Ven a comer,” his voice like a single candle lit, urging us warmly to go next door, where a light Lenten meal waited.

—

Leeanna T. Torres is a native daughter of the American Southwest, a Nuevomexicana writer with deep Indo-Hispanic roots in New Mexico. She has worked as environmental professional throughout the West since 2001. Her essays have appeared in various print and online publications (Blue Mesa Review, High Country News, High Desert Journal), as well as several anthologies, including Torrey House Press’s First & Wildest; The Gila Wilderness at 100 (2022), and Elementals: An Elemental Life, Vol. 5, forthcoming by Center for Humans & Nature Press (2024).