Verses to an Institution

New Mexico poets share odes to the New Mexico Museum of Art on the occasion of its centennial.

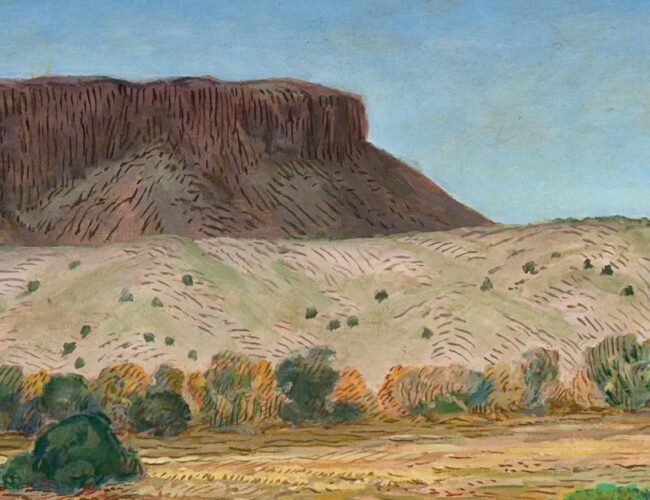

John Sloan, Little Black Mesa, 1945. Oil on Masonite, 19 15⁄16 × 24 in. Collection of the New Mexico Museum of Art. Bequest of Helen Miller Jones, 1986 (1986.137.22). Photograph by Blair Clark. © John Sloan Estate.

John Sloan, Little Black Mesa, 1945. Oil on Masonite, 19 15⁄16 × 24 in. Collection of the New Mexico Museum of Art. Bequest of Helen Miller Jones, 1986 (1986.137.22). Photograph by Blair Clark. © John Sloan Estate.

WHAT’S NOT LOST

Something happens

when there is an absence of

foundation

there is a direction chosen

where heart, intent, and desire, meet

intuition—where

preservation meets development

meets community

to set a precedent

for instances in which the likes of

MOMA follow suit.

Architecture and ancient character

conversing as if they’re

of two different tongues

but translation isn’t lost altogether—

instead a romantic erosion

set in motion

a revival that was

and remains

inherently difficult.

Yet performed with grace

and put in place

as Santa Fe Style,

Where seven sings of luck

like ceremony

like the planting of a seed

for means of interpretation

an authentic invitation

to the American avant-garde

What was once considered

to be hopeless and backwards in ways

saw a change —

a shift in the foundations

a brown and round revival

one that danced toward an identity

worthy of development

deserving of preservation.

Development of value

preservation of meaning

and the sustained promise

of authentic existence

abound—within these rounded

walls,

in these echoed halls

with floors that ache

to speak—oh the stories they’ve heard.

of creation

expansion

collision

dialogue and growth.

musings of inclusion

a unique revelation

a gift in the desert.

One of sand and mud

earth and sky

and everything in between

the in between,

it’s where we find ourselves,

now.

As cultures have clashed, coalesced

coalesced, clashed

Erosion, a term not quite

fitting, unless we aim

to find the beauty in what is lost,

the treasure that is story,

that is song,

that is memory until memories are gone.

and so here,

striking are the instances

of remembering—

where we came from

who we are

where we’re going.

100 years removed from this place in time

what might we find at this particular site

what will have beautifully eroded

into a quest for something more

to be questioned

to be brought about in the idea of

beauty, of belonging,

of story and legacy.

And where is that

Santa Fe horizon, somewhere else?

Likely anywhere

and that ought to be just fine to those

who have walked these halls

and shared in the

creation

the construction

the preservation

of beauty

in

art as response

in motion,

in memory,

forever.

—Carlos Contreras

Note

This is the latest in a series of commemorative poems El Palacio has commissioned from Carlos Contreras. He has also written “Along the Beaten Path” for El Camino Real (bit.ly/ecrpoem), “It Used to Be a Village” for Coronado Historic Site (bit.ly/chspoem), and “Communion in the Desert” (bit.ly/nmhmpoem) on the occasion of the opening of the New Mexico History Museum, among others.

A FESTSCHRIFT ENDING ON A DRAWING BY RICHARD TUTTLE

Window-glance of lilacs on adobe, a

light breeze and sunlight

shivering thin shadows on the wall,

tulips blading up

through loam and leaf-rot. From brush-

stroke and trowel-slip,

from windrow poplars leafing-out to

wind-dwarfed oak,

a shadowy yet lucid history—water

rushing the ditch-mouth,

rose and lilac rifted alike with

mountain light and thunderhead,

with elk-bugle, bear-chuff, bolete and

chanterelle, the silent rift

between first sight and pounce, the

lion shadowing the straggling lamb

like a painting that carries the heft of

gold-leaf, of clay and wool,

the arched stroke of horses, golden in

the mist-shrouded meadow.

We are like that newly-sighted woman

oppressed by the vituperations

Of shadow, of color—the bugled blues

and honking reds pressed hard

against her eyes, her ears, purpling

everything—a blastula of color,

a fistula, a fist that whelms and

overwhelms with newness

until the barest stroke of graphite—

part line, part silence—tacks

across a flat pond of lined paper, a

light hand on the tiller, buffeted

by chance, by the weight of sunlight

on penstemon—a breath so

gentle now across the earlobe carrying

just your whispered name.

—Jon Davis

MOONRISE OVER HERNANDEZ

The baby never slept, and if she did

it was only for ten minutes at a time.

She wasn’t distressed, simply inquisitive.

She didn’t want to miss out on anything.

At dusk I walked her in my arms around the Plaza.

The moon rising above Picacho Peak pleased her, the star

over Loretto Chapel illuminating the narrow streets of town.

We climbed the softly worn stairs of the museum,

the uneven wooden floors giving way under my feet like a

well-watered lawn.

She craned her head and stretched her arms toward the dark

vigas of the ceiling

with its carved red and blue bulleted pattern.

In a narrow room painted the green of a young ponderosa,

she gazed at Ansel Adams’ photographs,

moved her eyes across the southwestern sky of his prints,

pointing to the small white speck in the black sky

rising over snow-capped mountains, the river village of

Hernandez,

and said her first word, up.

—Elizabeth Jacobson

WHAT CAUGHT MY EYE

Would life be richer if the sunflowers blooming

Became tanagers and feathers flew out of the bird.

Maximilian yellow hit the George Bellows blue sky

I used to live below the abstract, adobe,

a tract house in the real. Our field flanked

La Mesita, inhabiting John Sloan’s masonite.

Oh Georgia, You drew me, lured by a skull,

a blue feud. I arrived and found a pelvis

by the road, caught is what I know about bone.

I ride this white painted horse home from the

“Rendezvous.”

My horse is in oil. My horse is in alfalfa.

A group from India passes between this life and my last.

Two of them take illicit photographs

next to two Hopi dancing in bronze,

a rattlesnake held in teeth

The man who donated his kidney strolls by.

Life always grabs me, rattle and fear,

Though my people rarely handled snakes.

Paint gasps for canvas.

We toss our lives back and forth, smile,

Handle what we dare.

—Joan Logghe

This poem was previously published in The Singing Bowl

(University of New Mexico Press).

THE REHEARSAL

Thunderheads above the Plaza,

a stop, a start—

guitar and violin rehearse.

One of those days

when conversations can go wrong

but the violinist is barefoot and cheerful

in hot pink and kelly green

and the guitar player smiles adoringly.

“It’s fantastic!” comes from the audience.

Rehearsals are confusing,

as is life,

the same problematic measure

over and over

and how many times I’ve looked

at these murals—

St. Clare rejecting the worldly life

in Pre-Raphaelite fashion.

The crucifix reaches higher

than the Mayan priest’s staff—

these images speak of conquest—

and Christopher Columbus

dreaming of a schooner’s

red sails at sunset.

Then Robert Schumann

Piano Quintet in E-flat,

the poor composer

dying in the insane asylum.

Yet it seems so amazing

to be walking around needing only

a stringed instrument

to produce these notes.

The piece so familiar to my ear

yet essentially unknown.

Notes falling and falling and falling.

How each person

in the audience

contains an entire world,

remains mysterious,

even to themselves.

Sorrow, greed, opinion, accomplishment, secrets, lunch.

Who can walk down an avenue

in a great city and say—

I am complete.

Now the violinist is playing the cello!

Showing off or to prove a point.

And the cellist is laughing.

—Miriam Sagan

EARTH AND WATER

At home, though out of place, caught in a spell,

like Rousseau’s nude drowsing on her jungle chaise,

a numinous radiant-white outsize shell,

suggestive, slyly, of a desert skull.

Painted in reverse, on the back of glass,

at home, though out of place, caught in a spell.

In the first brushstrokes, fine as filoselle,

the details are laid down: wisps of snake grass,

a numinous radiant-white outsize shell,

camper in which itinerant undine could dwell,

at any moment to emerge and gaze,

at home, though out of place, caught in a spell

under the creviced juniper, the swell

of distant mesas, now iconic as

a numinous radiant-white outsize shell.

An echo chamber, like a villanelle,

through which the rhymes of desert seas can pass,

at home, though out of place, caught in a spell,

a numinous radiant-white outsize shell.

—Carol Moldaw

THICK TIME

At dawn the Sangre de Cristos usher in slants of light;

all begins anew amid cool clean breezes

in the ancestral homeland of our relatives, the Kiis’áanii.1

Yootó2 is resplendent in the clear morning:

piñon, cedar and juniper, low red hills

and huge cottonwoods along the river

and the Plaza glisten in the new day.

They are eternal witnesses.

Near our home, the huge yellow chamisa are at their finest

in the bright September days though we admit

our detour around them due to their boisterous scent

and loud bees feasting on their nectar.

The young chamisa are perfectly round and stately;

their still-closed blossoms eager to debut in a few weeks.

They emerged in exact proportion to nearby stands

of brush, cholla, yucca and sage.

The crisp morning summons the sleek train

that is piloted by a bright yellow/orange roadrunner.

The car carries tourists who talk loudly though seated

together;

they are compelled to share their grasp of local food, cafes,

shops and pueblos.

Sullen students lug huge bags down the aisle then sling

them onto seats;

they are shielded by headphones and pause only to tap

intense texts into the world.

Solitary tourists keep watch on the landscape, snapping

pictures

of lone horses on the hills, the crimson bajada dotted with

green brush

and lone billowing cloud. Near the depot, they take selfies

suddenly smiling broadly and unabashedly

at their outstretched hand. The sudden action momentarily

startles others.

Fridays on the Santa Fe plaza:

slight winds carry enticing whiffs of hot dogs, burritos and

kettle corn.

Bright balloons rise languidly above shrill wails and

outstretched hands.

On the verandas above, people sip cool drinks, dine on spicy

dishes

or warm, crusty pizza. Their banter and laughter wafts

across joining

the din of children running about, that tall guy talking

boldly into his phone

and the teenagers huddled on the grass sharing smoke

their hushed voices punctuated by occasional whoops of laughter.

The huge, leafy cottonwoods regard the stooped elder who

treads warily;

she pauses to watch the children carelessly bound ahead.

She smiles

and recalls those delicious days when she too was light and

untethered.

Ecstatic little dogs struggle to sniff every inch while minding

their “good dog”

status lest they are picked up. It’s torture to be carried in

such a delectable place!

Near the Obelisk, a busker strums guitar while silently pleading

for another bill, or better yet, a fiver. As graying hair falls over

his bowed face, he recalls the long-gone years of dim smoky

bars,

rowdy laughter, fanciful undying camaraderie, cold sweaty

cans of beer

and that huge clear bowl stuffed with bills.

“Ah, Kentridge, the residue of the past is very much with

us,”3

he says to himself and smiles.

At the museum, my footsteps creak on the worn wooden floor,

Along the court yard pink hollyhocks and cerise roses

are radiant against the thick earthen walls.

The portals play annual hosts to strands of shiny, fresh ristras;

their deep, red iridescence a celebrated contrast to turquoise

skies.

Inside the dim museum, security guards politely shush

patrons,

whisper restroom directions then move about silently.

I wander through the halls and consider lines, colors,

angles of light and time conceits in varied works as

Maria Martinez, Scholder, Houser, Rembrandt and Picasso.

The echo of each scribble, line, stroke of pen, brush or yucca

leaf

gesture from each frame, from decades, and centuries ago.

Later, I sit beside the Santa Fe river where the fluttering

cottonwoods

evoke my ancestors’ long-ago journey to Yootó.

In the mid-1860s, the Diné were rounded up by the U.S. Army.

They were to be imprisoned at Fort Sumner,

but were first marched through Santa Fe to quell fears

about “marauding” Navajos and Apaches.

To the capturers’ surprise, the townspeople attacked the weary

disheveled children, elders and families.

They threw sticks, rocks and some even kicked and struck them.

Alarmed, the military formed a protective circle around them

then finally led them southward on the 200-mile walk to

Ft. Sumner.

The Diné were held there for four years then released in 1868.

In the afternoon din, I stretch my arms

and straighten my back: a reminder to maintain posture.

I see myself as others might: a Diné woman alone in Santa Fe

though I am bequeathed again with prayers, songs, and memory.

I understand that the huge trees, the cold river, dark velvet

mountains

and even the thick brown walls recognize me.

They bid me to return so as to cherish our ancestors,

and the multitude of gifts that surround us.

We are bidden to remember their journeys

as we prepare for the days ahead.

—Luci Tapahonso

Notes

- The Pueblo people.

- Yootó is the Navajo name for Santa Fe, meaning a necklace made of beads of clear cold water.

- William Kentridge, Arc Procession 9. Lines of Thought: Drawing from Michelangelo to Now. New Mexico Museum of Art. September 2017.

- Diné means “The People” in Navajo.

THE REHEARSAL AT ST. FRANCIS AUDITORIUM

Xylophone, triangle, marimba, soprano, violin—

the musicians use stopwatches, map out

in sound the convergence of three rivers at a farm,

but it sounds like the jungle at midnight.

Caught in a blizzard and surrounded by wolves

circling closer and closer, you might

remember the smell of huisache on a warm spring night.

You might remember three deer startled and stopped

at the edge of a road in a black canyon.

A child wants to act crazy, acts crazy,

is thereby sane. If you ache with longing

or are terrified: ache, be terrified, be hysterical,

walk into a redwood forest and listen:

hear a pine cone drop into a pool of water.

And what is your life then? In the time

it takes to make a fist or open your hand,

the musicians have stopped. But a life only stops

when what you want is no longer possible.

—Arthur Sze