Spoon to City

Alexander Girard’s genius: tasty, urbane, and infinitely scalable.

Miller House, Columbus, Indiana, USA, Alexander Girard, 1953–57. Photograph by Balthazar Korab. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Miller House, Columbus, Indiana, USA, Alexander Girard, 1953–57. Photograph by Balthazar Korab. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

BY LAURA ADDISON

In a 1953 letter to friends back in Michigan, designer Alexander Girard enumerated what appealed to him about Santa Fe, his new hometown. Tellingly, his description engaged all the senses. He spoke of New Mexico’s “crystal clear, crisp air,” the feel of the hot sun, the fires “that smell like incense,” the views of horses, goats, and cows from their home portal, the sound of singing processions, and the multisensory allure of nearby bonfires. Girard also gravitated to northern New Mexico because it was home to Native American, Spanish Colonial, and Mexican communities, whose arts he avidly collected.

Girard spent his most productive and creative years, 1953 through 1993, in Santa Fe. In choosing New Mexico, he joined a long line of artists, writers, and other inventive individuals who found creative nourishment here. Girard’s visual language brimmed with bold colors, complex patterns, and dynamic figures and forms. His great contribution to the design field, according to fellow textile designer Jack Lenor Larsen, in his essay “A Celebration of the Senses,” was “to inject the lively human qualities of joy and spontaneity into what was probably one of the driest, sensually impoverished chapters in the history of design.”

The traveling exhibition Alexander Girard: A Designer’s Universe is the first comprehensive retrospective of Girard’s design work. Organized by Germany’s Vitra Design Museum, it draws from the designer’s estate, which was donated to Vitra in 1996, three years after Girard’s 1993 death. The exhibition’s generous selection of his designed textiles, furniture, tableware, sketches, and more details how Girard engaged the senses and influenced modern design. A Designer’s Universe also illustrates Girard’s rich creative life, from the invented worlds of his youth to his mature work as one of the pioneers of modern design.

Visitors to the Museum of International Folk Art are familiar with Girard’s awe-inspiring displays in the museum’s long-term exhibition Multiple Visions: A Common Bond, in which Girard staged approximately 10,000 toys and folk art in various imagined worlds. The design side of Girard’s creative life has not been showcased as prominently, and this exhibition is a welcome corrective.

These two exhibitions—A Designer’s Universe and Multiple Visions—seen together at the Museum of International Folk Art from May 5 through October 27, 2019, provide a rare holistic view of Girard’s creative virtuosity.

Born in New York in 1907, Alexander Girard grew up in Florence, Italy. While attending boarding school in England, he created a fictional country called the Republic of Fife, complete with designs for stamps, currency, heraldic banners, maps, and a secret language of symbols. A Designer’s Universe opens with this fascinating first glimpse into Girard’s imagination. In the exhibition, the Republic of Fife inhabits a distinct wooden structure—a gallery within the gallery—that the viewer enters through a rounded arch to encounter these colored-pencil drawings from Girard’s youth. In one drawing, done in a journal, two bearded figures face each other in European-style costume, one holding a shield, the other a sword. The colorful heraldic imagery on their costumes relates to the banner each carries. Stamped on the journal page is text that reads, “Fife Republic Post, Dec 1923.” Here, fiction meets the Italian influence in which Girard’s childhood was steeped.

Standing within the Republic of Fife structure, the viewer is introduced to the idea that Girard designed discrete spaces that came alive with color, pattern, and structure, an idea that carried through Girard’s entire design career. From his earliest years to his later designs, Girard created spaces where the serious and the fanciful commingled. The Republic of Fife presages the worlds Girard would later imagine in the miniature theaters he would construct with his toys and folk art in the exhibitions The Magic of a People at San Antonio’s HemisFair (1968) and Multiple Visions at the Museum of International Folk Art (1982).

Girard moved back to New York City in 1932, after studying architecture in London and Italy. After five years in New York, he and his wife, Susan Needham Girard, moved to Michigan. Eager to embrace the opportunities available in this industrial and automotive hub, he established a design studio near Detroit. Here, Girard worked for Detrola, among other clients, designing everything from the corporate cafeteria to radio housings. He also helmed several iterations of a design store, where he curated exhibitions and sold his work, including fanciful toys.

In 1951 Girard was hired as director of the textile division of the Herman Miller furniture company, located in Zeeland, Michigan, outside of Grand Rapids. Two years later, the Girard family, Alexander (also called Sandro), Susan, daughter Sansi and son Marshall, relocated to Santa Fe.

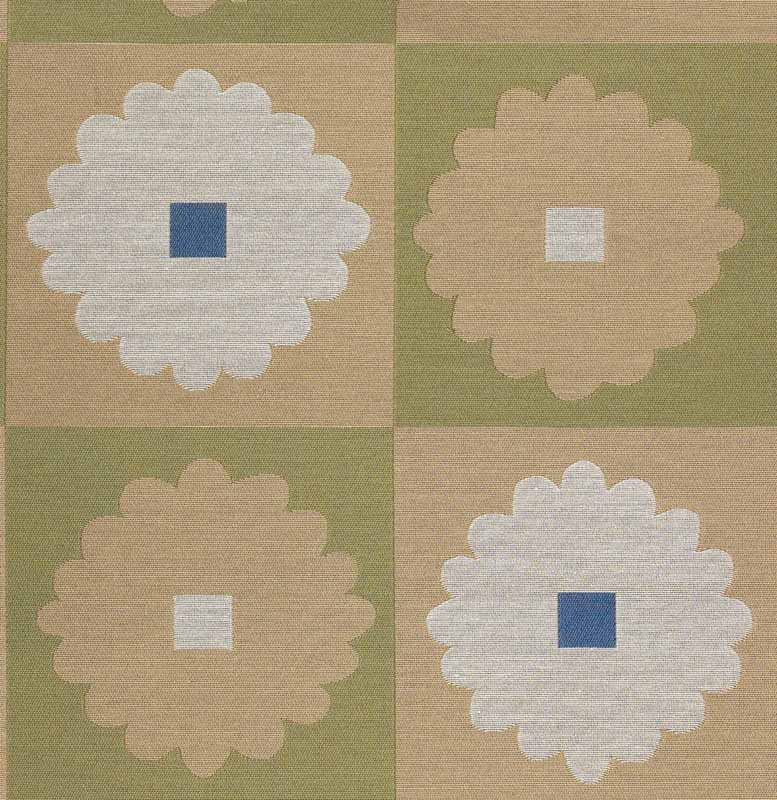

Santa Fe became Alexander Girard’s home base for numerous projects, including his ongoing work for Herman Miller, which eventually numbered more than 300 textile designs. As A Designer’s Universe curator Jochen Eisenbrand states, for Girard, textiles were a building material, as important to architecture as brick, glass, wood, and plaster, and the exhibition includes many of these textile designs, installed in dramatic fashion. Yards of fabric swoop from the ceiling and unfurl down the walls in the show’s dynamic installation. Patterns such as Ribbons, Feathers, and Mikado are among the textile designs. The repeating patterns—primarily geometric or floral—lent themselves to upholstery and drapery applications. Mikado, from 1954, is a reminder of Girard’s early interest in global culture. The textile’s stylized chrysanthemum represents the symbol of the Japanese mikado, or emperor.

A Designer’s Universe also includes a number of textiles from Girard’s best-known collection, the Environmental Enrichment Panels. Girard designed these panels in the early 1970s in an attempt to humanize the coolly efficient modular Action Office System which Robert Propst designed for Herman Miller. When he was tasked with psychologically improving the outlooks of office workers, he found the available textiles to be inadequate. And so he created his own. This concept of “aesthetic functionalism” became a defining part of Girard’s legacy. While some of the Environmental Enrichment Panels made use of repeated patterns such as a cloud of stars, an arrangement of bricks, or a maze of interlocking knots, others featured figurative, stylized images.

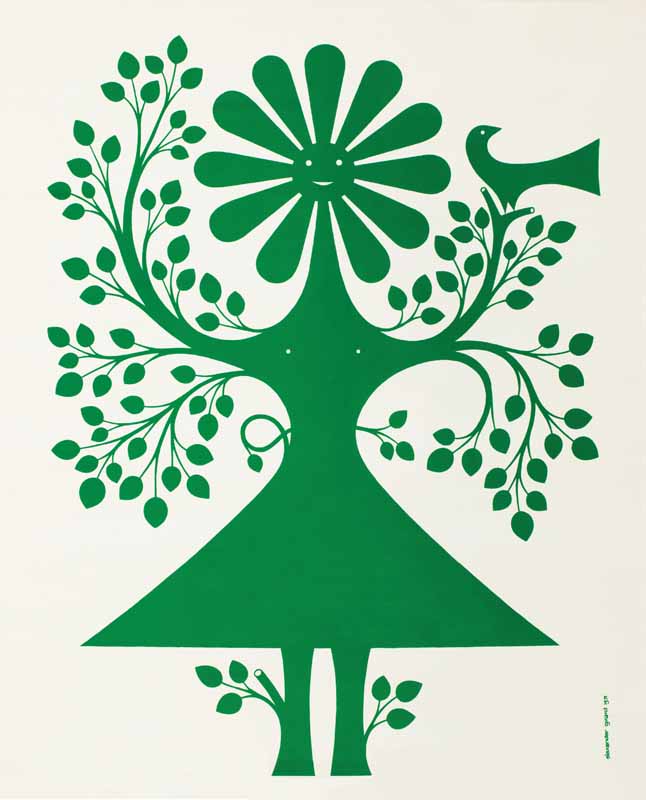

Girard intended Love Heart (page 35) to make the office cubicle a more colorful, joyful site for productivity and work satisfaction. Daisy Face (page 34) is a single anthropomorphized tree in emerald green. Its dual trunk-legs spring from the earth and sprout leaves from the knees. Branches replace arms and the silhouette of a flower represents the head. A bird, one of Girard’s recurring motifs, perches on the figure. She seems to gaze directly at the viewer—offering a dose of nature and encouragement to cubicle-anchored corporate employees.

Both Love Heart and Daisy Face illustrate how Girard engaged the senses and the imagination through the use of bold colors, graphic simplicity, and patterned complexity.

Girard’s portfolio was remarkably varied—from residential and corporate interiors to the main-street facades of Columbus, Indiana; from table settings and restaurants to the bold new graphics of Braniff International Airways; from typography to exhibition design. In short, Girard was known as a designer who would take on any design challenge. To use a phrase coined by the Italian architect Ernesto Nathan Rogers, Girard employed a “spoon to city” approach to design. Though perhaps less widely known than his textiles, his designed environments were equally important to design history and Girard’s legacy.

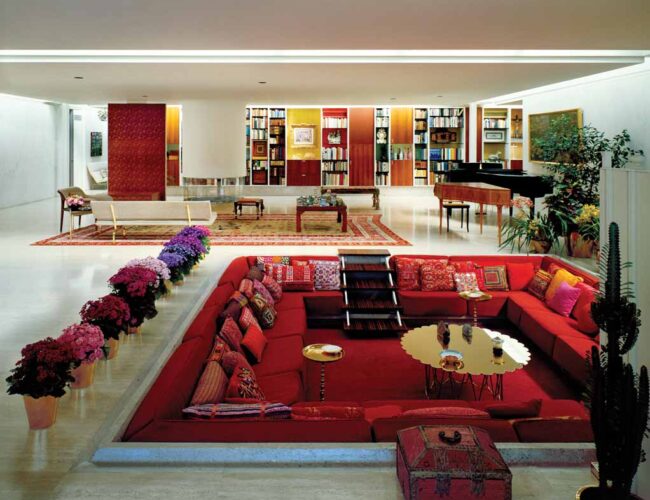

Through rich assemblages of objects, sketches, and video projections, A Designer’s Universe offers a close look at some of Girard’s designed environments, including the restaurants La Fonda del Sol [see El Palacio’s spring article, “A Dazzling Denizen,”] and L’Etoile, as well as his residential designs for the Miller House in Columbus, Indiana, and his residence in Santa Fe. Eisenbrand has observed that Girard’s home “served both as an experimental laboratory of sorts and as a showcase for his ideas regarding a modern lifestyle.” The exterior of the house was painted with vibrant blocks of color. Inside, he installed wall-mounted shelving systems, and displayed collected folk art pieces in nichos. His family and their friends gathered in the house’s conversation pit, or below-grade seating area. In a Los Angeles Times interview Girard said, “Your household becomes a ‘theater’ in which you live with the scenery. Among the props will be a few high-quality furnishings and a vast array of entertaining and temporary expendables.”

The design of the exhibition A Designer’s Universe by Raw Edges of London references Alexander Girard’s own designs. The swooping fabrics that greet visitors upon entering the textile room cite Girard’s exhibition design for The Design Process at Herman Miller at the Walker Art Center. The layered effect of the image-and-artifact displays in his designed environments echoes Girard’s layering of fabric and objects in the Herman Miller Textile & Objects Shop as well as his installation strategy for a dimensional history mural he did for John Deere. The gallery-within-a-gallery concept for the Republic of Fife display echoes MOIFA’s own chapel within the Girard Wing that houses religious folk art from around the world. And the seating area of A Designer’s Universe includes a kaleidoscopic and encyclopedic array of Girard fabrics upholstering the cushions, a nod to one of Girard’s signature interior elements—the conversation pit—which made its appearance most famously in the Xenia and J. Irwin Miller House in Columbus, Indiana (page 30). Girard’s ethos was never about isolated objects, but rather the richness of relationships: not only between a room and its furnishings, but an altruistic intimacy between humans and their designed environments.

Alexander Girard: A Designer’s Universe is organized by Vitra Design Museum. Global sponsors are Herman Miller and Maharam. The exhibition is on view May 5 through October 27, 2019 at the Museum of International Folk Art.

Laura Addison is curator of North American and European Folk Art at the Museum of International Folk Art.