Finding Their Niche

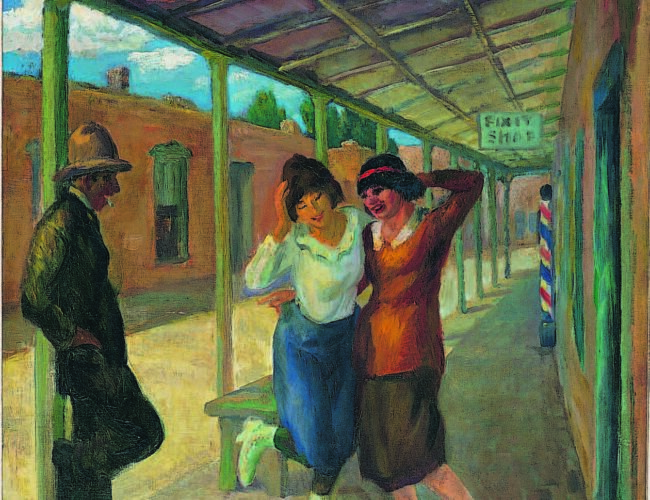

John Sloan, Under the Old Portal (Old Portale, Santa Fe), 1919 (reworked 1945). Oil on canvas, 24 × 20 in. Collection of the New Mexico Museum of Art. Gift of Julius Gans, 1946 (22.23P). © 2016 Delaware Art Museum/Artists Rights Society (ARS) New York. Photograph by Blair Clark.

John Sloan, Under the Old Portal (Old Portale, Santa Fe), 1919 (reworked 1945). Oil on canvas, 24 × 20 in. Collection of the New Mexico Museum of Art. Gift of Julius Gans, 1946 (22.23P). © 2016 Delaware Art Museum/Artists Rights Society (ARS) New York. Photograph by Blair Clark.

BY KATE NELSON

The New Mexico Museum of Art’s early alcove shows drew waves of artists to Santa Fe and defined it as a top US art city.

Before Santa Fe could grow into an international art destination with an art museum poised to hit its centennial in 2017, an art-world anarchist had to meet an archaeology-mad town booster while neither was anywhere near New Mexico. Serendipity played its part. The two got help from artists eager for new vistas, from a world war and a tuberculosis outbreak, from a spanking-new state steeped in eons of history, and from a sky so beautifully turquoise and so often lauded that to this day, praising it has yet to get old.

The artist-cum-anarchist, Robert Henri, founded the Ashcan School in New York City at the turn of the century. Besides encouraging a loosely classical approach to portraying the darker side of urban life, he also mentored a number of artists whose friendships would soon lead them to a rural outpost with one railroad, few roads, and that big, inspiring sky. Edgar Lee Hewett, the town booster, set the lure with what became the New Mexico Museum of Art. He sweetened the deal with offers of free studio space and, upon Henri’s insistence, an opportunity for artists both emerging and established to hang their works in the prominent alcoves of a bona fide professional museum.

At a time when Santa Fe counted few artists and no art galleries, you could imagine that East Coast, studio-trained painters and sculptors sensed a tectonic rumble somewhere in the distance, way out West. Their response to it changed the game in New Mexico, culturally and economically, as boldly as the Manhattan Project would just three decades later. The origin story, though, is set in 1914 San Diego, during the frenzied buildup to the Panama–California Exposition, on an uncertain but fabled date: when Henri met Hewett.

Hewett knew Santa Fe needed a place to show art other than the tight confines of the Palace of the Governors, which he had only recently rescued from demolition. As founder of the Museum of New Mexico, he rightly suspected that serious artworks and a clutch of working artists would attract tourists and new businesses to a town that was just being wired for electricity and had burros to thank for firewood deliveries. Hewett’s plans for a new museum in Santa Fe were sidelined when, shortly after statehood was granted, the 1915 Panama–California Exposition presented an irresistible option to show off New Mexico’s cultural assets.

Hewett’s credentials as an archaeologist had earned him oversight of the fair’s ethnology and art exhibits. Most of what he dreamed up celebrated Southwestern tribes. For a counterbalance, he asked Alice Klauber, a member of the Fine Arts Committee, to set up a contemporary art exhibit. She turned to her former art teacher, Robert Henri, who just happened to be living in La Jolla, California. Henri and Hewett hit it off, and their alliance continued when Hewett headed back to Santa Fe.

There, plans to build an art museum resumed, and Henri soon shifted the direction of how it would operate. His concept came to be known as the “open-door philosophy,” which meant any artist could add their name to a list, await an open alcove within the museum’s main, first-floor gallery, and present what they wished without the imprimatur of a hoity-toity art academy. (Hewett’s motivation was at least partly prosaic: the new museum had no collections to exhibit and no curators to organize exhibitions.)

“This was huge for artists,” says Mary Kershaw, director of the Museum of Art. “Henri was an East Coast art teacher, but he was also anti-academic. He felt artists were too constrained by institutions, curators, and critics in how they showed. To have this powerful, important building and to be showing within it made a statement about art.”

With Europe at war, the standard means of artistic training—tours of highly regarded art academies from Italy to England—was unavailable. Bolstered by their era’s spirit of Americanness and individual freedom, artists gleefully threw off that yoke. Regional art colonies had sprouted elsewhere. Santa Fe sounded a call to experience the new landscapes and exotic peoples of New Mexico’s high desert. Artists soon arrived, some for a visit, some for good. Upon the museum’s grand opening on November 25, 1917, El Palacio reported a roster of exhibiting artists who came to define the new breed:

Henry Balink; George Bellows; Oscar Berninghaus; Ernest L. Blumenschein; Paul Burlin; Edgar S. Cameron; Gerald Cassidy; Kenneth Chapman; Mrs. E.E. Cheetham; E.S. Coe; E. Irving Couse; Leonard H. Davis; Katherine Dudley; Helen Dunlap; W. Herbert Dunton; Lydia Dunham Fabian; W. Penhallow Henderson; E. Martin Hennings; Robert Henri; Victor Higgins; Leo F. Hirsch; Alice Klauber; Leon Kroll; Ralph Meyers; Arthur F. Musgrave; Sheldon Parsons; Bert G. Phillips; Grace Ravelin; Julius Rolshoven; Doris Rosenthal; Joseph Henry Sharp; Eve Springer; G.C. Stanson; Walter Ufer; Mrs. Walter Ufer; Theodore Van Soelen; Carlos Vierra; and Mrs. Cordelia Wilson.

Some of them donated their works to the museum’s empty collections bin, including Henri’s eternally popular Portrait of Dieguito Roybal, San Ildefonso Pueblo. With the advent of the rotating shows within alcove spaces, artists began sharing not only their latest interpretations of New Mexico and New Mexicans, but also items from their personal collections—Chinese paintings, Sioux ledger drawings, Indonesian textiles— broadening visitors’ access to art of all kinds and serving as cross-cultural muses for their fellow artists’ evolutions.

“It was a time of industrialization, and the artists had a big interest in anything hand-crafted,” says Merry Scully, the museum’s head of curatorial affairs. “Things were prized because of both their quality and because they were hand-crafted. So you see Japanese wood-block prints, and those things were also influential to the artists who were exhibiting.”

By 1920, some eighty artists had come to Santa Fe to work. Their shows rotated in and out so rapidly that, Scully says, “I wouldn’t be at all surprised if people painted in their alcove and then hung it up.”

Evidence of how the alcoves worked is scant and mostly pieced together from El Palacio articles that leave numerous questions hanging. Nevertheless, MaLin Wilson Powell, who curated the museum’s 2014 exhibit, Alcove Shows 1917–1927, says she was heartened during her research to see the mix of locally produced art and international collections. Equally impressive was that women artists were represented nearly half the time. “The sorry thing for me,” she adds, “was the things that went into the permanent collection were primarily works by men. I don’t know why that was.”

Also discouraging was the lack of Native and Hispanic artists. Despite the growth of the Santa Fe art scene, many of those who got to stand on center stage were Anglos who sometimes engaged in romantic portrayals of stoic Indians, humble Hispanics, and idealized landscapes.

“You’ve got a largely transplanted, Anglo, male coterie appropriating and manipulating Hispanic and Native American art,” says Chris Wilson, author of The Myth of Santa Fe: Creating a Modern Regional Tradition (University of New Mexico Press, 1997). “They’re doing it for tourism promotion, and they’re using other cultures for economic development. But myths are positive and negative. The city became an intellectual and cultural center with a great deal of power beyond any city of comparable size. One positive side effect was that Pueblo and Hispanic intellectuals were part of that milieu and, even if they weren’t exhibited, they developed their own media. It was a magnet.”

The milieu included work well known to any artist: stuff that sells. What the tourists wanted, the artists made. In one way, it gave birth to Santa Fe schlock, but in another, it fostered relationships among all artists, who shared ideas, books, materials, and techniques. In 1921 the Third New Mexico Loan Exhibition was announced in El Palacio. It appears to have been a sweeping show within the museum’s alcoves, each of which was named for one of New Mexico’s pueblos. Some 185 works by Anglo artists were arrayed on the walls of alcoves and staircases, along with 17 works by Pueblo artists—Awa Tsireh, Crescencio Martinez (Ta’É), and Velino Shiji (Ma Pe Wi). Eventually, artists based in both Taos and Santa Fe formed the Indian Arts Fund to foster top-notch Native artistry and set a figurative bulwark between those artists and the people who would happily spirit from the state both ancestral treasures and slapdash work.

“Dr. Edgar Lee Hewett . . . does much for the artists there,” artist John Sloan told the New York Times in 1922. “Too much cannot be said about him. He is always in sympathy. There are three galleries in the New Museum where the work of the artists can be hung. Santa Fe is on the route to the coast for automobiles, and in that way a good many tourists pass through and always visit the Museum and the old Governors Palace.”

It had worked. Artists were flocking to Santa Fe. Sloan and his wife now called it their part-time home. He and other artists showed their works not just in New Mexico, but also in New York, Chicago, and other American art capitals. The locale so inspired them that, when Randall Davey had his first New York City show three years after leaving for New Mexico, a reviewer in the May 1, 1922, El Palacio pronounced him a changed artist: “Of old . . . he looked through Velázquez darkly. But now he looks man and nature face to face. And the contemplation of man and nature, freed from the artificialities of city life, or art exhibitions, and of the (unconscious, perhaps) domination of various artistic personalities, has caused him to put off many of his former mannerisms and emerge from the high solitudes of Santa Fe a ‘new Randall Davey’ in view and deed.”

The artists received gushing attention from El Palacio, which reported on where their houses were, what other countries they visited, which out-of-state museums exhibited their works, how they were reviewed, when they arrived in Santa Fe for a visit, and when they left. In 1920 artist Will Shuster sought a high-and-dry cure for tuberculosis here and stayed. He helped form Los Cincos Pintores and, with fellow transplant Gustave Baumann, added elements like Zozobra and the Historical/Hysterical Parade to Hewett’s reinvented Santa Fe Fiestas. In 1925 Edward Hopper briefly abandoned his urban view to produce thirteen paintings of such thoroughly Santa Fean scenes as the towers of St. Francis Cathedral peeking over rumpled adobe buildings in a very Hopper-like foreground. From 1927 to 1931, transcendentalist Raymond Jonson organized thirty-two exhibitions in the museum’s “Modern Wing,” the precise location of which remains a mystery.

Auxiliary businesses came, too. Alice Corbin Henderson, the poet and wife of artist William Penhallow Henderson, opened the Santa Fe Print Shop. The first art gallery opened in Sena Plaza in 1925, and curio shops grew from four in the 1920s to sixteen in the 1930s. Hotels sprouted. The Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway took over La Fonda, and the Fred Harvey Company inaugurated its Indian Detours to nearby pueblos. After World War II, a population boom landed in New Mexico. By the 1950s, hotel lodgings had increased sevenfold from the museum’s maiden year.

Over those decades, grateful artists gave the museum pieces that became hallmarks of its collection and illustrated a virtual textbook on the roots of southwestern style. The 1921 exhibition featured a few, including Marsden Hartley’s El Santo; Leon Gaspard’s Portrait, Sheldon Parsons; Sven Birger Sandzén’s Alone in Their Majesty and Above Timberline; and Sheldon Parson’s Santuario. By the 1950s, the museum held enough art to mount its own exhibits. Artists crowded onto a lengthy waiting list for scant alcove time. Hewett’s 1921 pronouncement of the open-door policy, as stated in El Palacio, teetered on a precipice:

The people of New Mexico have a priceless opportunity. Here passes before their eyes from day to day and year to year a panorama of the esthetic efforts of a characteristic group of artists whose works are challenging the interest of the whole country. The Museum extends its privileges to all who are working with a serious purpose in art. . . . The artist is the judge of the fitness of his work for presentation to the public to the same extent that the speaker is who occupies our platform. Both are conceded perfect freedom of expression within the limits of common propriety.

But change had come. In 1951 the museum announced a new course of juried exhibitions. Some artists rebelled. Rousted from what became his deathbed in Hanover, New Hampshire, Sloan fired off a telegram to Shuster: “I have just heard that S.F. Art Museum is having its first Juried Ex.—STOP! . . . Robert Henri and Edgar Hewett will ‘turn in their graves’ muttering— STOP. The ‘Open Door’ might have let in Publicity, Honesty, Equity. The jury will cause all these to—STOP.”

“You can’t run an institution with any kind of consistency by continuing the open door,” Scully says. “Contemporary art was becoming more professional. You needed some kind of structure. Early museums were very idiosyncratic. As people began to expect certain types of things, museums needed to change—and they needed to change to have longevity.”

The alcoves are still there, and the museum revived permutations of alcove shows at various times beginning in 1980s. Scully oversees their latest incarnation, drawing together eclectic mixes of artists practicing every type of media for five-to-seven-week shows that encourage face-to-face dialogues with patrons and fellow artists. “It’s always been hard to be an artist,” Kershaw says. “I think what the museum did was offer a real focus for the art community and create a critical mass. Opening this museum literally helped raise the awareness.”

Today, Kershaw loves walking through that part of the museum where Gerald Cassidy’s classic and beloved Cui Bono? stands sentry on an alcove wall—a marker of a time when a new museum welcomed artists just learning how to interpret New Mexico and, even then, questioning their interpretations. (Cui Bono?, Latin for “who benefits?”, poses a Taos Puebloan in terms both heroic and gauzy, the past meeting an uncertain future.) “Transport yourself back 100 years,” Kershaw says. “That piece in exactly the same space is contemporary art. I love that combination of continuity and recognition—that change happens no matter what we do.”

Kate Nelson is the managing editor of New Mexico Magazine and author of the biography Helen Hardin: A Straight Line Curved.