Provisions for the Soul

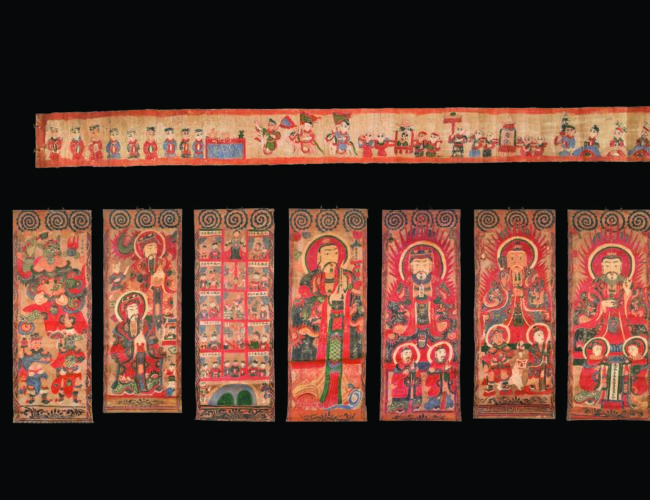

The Dragon Bridge of the Great Dao, Yao culture, late nineteenth–early twentieth century, China. Paper, natural pigments, fiber cord, bamboo, 6 5⁄16 × 167 11⁄16 inches. Gift of Michael Goh, The Lost Heavens, Museum of International Folk Art (A.2014.57.1). Photograph by Blair Clark.

The Dragon Bridge of the Great Dao, Yao culture, late nineteenth–early twentieth century, China. Paper, natural pigments, fiber cord, bamboo, 6 5⁄16 × 167 11⁄16 inches. Gift of Michael Goh, The Lost Heavens, Museum of International Folk Art (A.2014.57.1). Photograph by Blair Clark.

BY TRIAN NGUYEN

The Yao objects in the Museum of International Folk Art’s Sacred Realm exhibition have eye‑opening stories to tell.

Colorful and detailed, Yao ceremonial paintings and other ritual objects tell us stories about Yao cosmology and the status or rank of the shaman who used them.

The Yao are a large ethnic minority group who reside in the mountainous regions of southern China and the northern mainland areas of Southeast Asia. Originally from Hunan, during the Ming (1368–1644) and Qing (1645–1912) dynasties many Yao groups migrated to highland areas of northern Vietnam, Laos, and Thailand from mountainous provinces of southern China: Guizhou, Guangdong, Guangxi, and Yunnan. While Yao subgroups are differentiated by spoken languages and distinct forms of traditional dress, what unites them is their shared written language based on an archaic form of Chinese, a common ethnic ancestor (Pan Hung), and Daoism, the backbone of the Yao’s religious practices and beliefs.

The Yao honor the Three Pure Ones as the creators of the universe and all beings, and worship the Jade Emperor as the supreme ruler of the cosmos. They believe Daoism’s magic formulas and mystical rituals can help them endure life’s challenges. Pan Hung is a divine, protective being. Legend has it that when Yao descendants crossed many bodies of water to migrate south into the highlands of Southeast Asia, they ran into severe storms and prayed to Pan Hung. He sent his armies to their rescue and is seen as a great protector.

In Yao Shamanism, carefully crafted objects play roles in life’s most important rituals, and have religious and cultural significance, functions, and meanings. Those functions and meanings all relate to safety, protection, good health, and good fortune for families and communities.

Because the Yao often migrated from place to place in ancient times, they typically do not have permanent temples for communal worship. Rather, important ceremonies are conducted in homes, where temporary shrines are set up with hung paintings and ritual offerings.

In recent decades, many ceremonial paintings and ritual artifacts have found new homes in private collections or public museums, which gives more people a chance to better understand Yao culture. While any sacred item that is on display, particularly in a museum, is removed from its original context, it can still serve as a window into traditional aspects of cultures (as in the case of the Yao) that are in danger of disappearing as its society’s values change.

The Museum of International Folk Art has an extraordinary collection of Yao ceremonial paintings and other ritual artifacts in the exhibition Sacred Realm: Blessings & Good Fortune Across Asia. One of the museum’s sets of ceremonial deity paintings and four paper deity masks come from a single shaman’s collection.

Deities dwell in consecrated paintings, and Yao shaman priests use them as devotional objects of worship. Yao ceremonial scroll paintings depict not only members of the Daoist pantheon, but also legendary figures of folk religions, their original ancestors, national heroes, and popular Buddhist deities and divine beings.

Painted on mulberry paper, Yao ceremonial paintings were typically commissioned by a patron and produced by Yao or Chinese artists. Traditionally, painters observed strict behavioral rules and proscriptions when making the ceremonial paintings, and resided in a small, purified room near the main house of the commissioner. Upon completion of the painting, the owner invited high shamans to perform an “eye opening” ceremony, inviting the deities to dwell in the new paintings. Without this ceremony, a shaman could not use them for rituals. If the owner died, the paintings had to be burned, or the whole set was transferred to a new owner after an “eye closing” ceremony was performed to invite the gods to leave the painted scrolls, rendering them profane. If the next owner wanted to use the paintings ritually, another eye opening ceremony would have to be performed.

The Yao believe that a man must undergo an initiation ceremony, known as the Three Lamps Hanging Ritual, to become a mature and fully recognized member of Yao society. It is the first of the three major rituals (of three, seven, and twelve lamps) necessary to become a shaman priest. The lanterns’ light represents knowledge, wisdom, and spiritual insight transmitted from master to disciple. The ritual confirms that the participants are true descendants of Pan Hung, and bestows on them the blessings of the ancestors and deities. After death, it ensures entry into heaven to reunite with ancestors, or reincarnation, thus avoiding the severe tortures of the underworld.

To Become a Shaman

In order to conduct ritual services, all shamans must possess a set of three basic deity paintings. Low-ranking, novice shamans start out with paintings of deities who govern the palaces of life and death, including the Heavenly Hosts (an assembly of all the Daoist deities); the High Constable, Tai Wai (the Jade Emperor’s assistant, who helps the supreme ruler give blessings to human beings); and the God of the Sea, Minor Hoi Fan (the guardian of the Yao). The basic set of three in MOIFA’s collection, from the Red Dao (Yao) culture, was created in southern China in 1879.

Gaining Status as a Shaman

To become a high Yao shaman priest, the novice must study advanced rituals (including chanting and magical spells) with a senior shaman. He also learns how to read and write Chinese in order to compose petitions to supreme gods, and receives full ordination with the Seven Lamps Hanging Ritual.

In order to perform important rituals such as funerals and weddings, and those related to daily life—planting crops, water and its guardians, human illnesses and their associated spirits, and fertility—the high shaman priest is required to own a set of thirteen paintings. This thirteen-painting set is added to his basic set of three paintings and becomes a full set. Like the basic set of three, MOIFA’s full set is from the Red Yao culture but was painted about twenty years earlier.

The Three Pure Ones—the Jade Pure One, the Supreme Pure One, and the Grand Pure One—are the highest gods in the Daoist pantheon. Regarded as the creators of all beings and all the universe, they are the pure manifestation of the Yao— primordial celestial energy. An inscription on the back of the painting of the Jade Pure One, the central painting of the set, identifies the owner and the painter, gives a blessing, and names the full set: The Jade Pure One’s Sacred Realm.

The Three Pure Ones are depicted as elderly deities dressed in ceremonial court robes and hold sacred objects in their hands. As in all paintings of the Three Pure Ones, the Jade Pure One is seated at the center with two female attendants holding a banner inscribed with a short phase, a prayer for longevity for the current ruler. On the right is the Supreme Pure One, and on the left is the Grand Pure One. The halos around their heads radiate with divine flames.

The other paintings depict deities of various ranks with different administrative roles in the sacred realm. The Jade Emperor (not to be confused with the Jade Pure One) and the Master of the Saints are the two most important administrative gods in the Daoist cosmology. As the supreme ruler of the universe, the Jade Emperor has the power to appoint, dismiss, reward, and punish all beings. The Master of Saints is in charge of the twenty-eight constellations. Together, they are invoked to terminate evils and bestow happiness and long life. Except for the ceremonial tablets in their hands, inscribed with their titles, their features, costumes, and two attendants are indistinguishable.

Some paintings are more narrative. Major Hoi Fan, the God of the Sea, guides a shaman postulant on his path to advance his religious vocation. The high shaman is married with a family and has a high social status. To display his powers, the postulant must show his magic skills, such as climbing on a ladder made of sharp swords without being injured, and learning from Major Hoi Fan to swallow a hot iron plough without being burned. As illustrated in The Major Hoi Fan (fourth from right on page 73, in the full set of painting scrolls), only women who are married to high shamans and who received the Seven Lamps Hanging Ritual are recognized as official members of the religious path and are welcomed into heaven with their husbands after death, as seen in the exhibition in the long painting scroll The Dragon Bridge of the Great Dao.

A shaman’s rank increases with experience, knowledge of rituals, social status, and financial means. He is increasingly expected to be able to perform more complex rituals, and must add more paintings and ceremonial objects to his collection and his ritual work. These include paintings of the Four Heavenly Messengers, the Dragon Bridge of the Great Dao, a ceremonial dragon robe, and ritual masks.

These paintings are displayed during initiation ceremonies, funeral services, and ceremonies honoring the ancestors. The Four Heavenly Messengers are Daoist deities who connect the human realm with the unseen spiritual worlds and pass messages between heavenly realms. Their tasks include keeping track of people’s good and bad deeds and time spent praying, and reporting this information to the higher deities in the court of the Jade Emperor, who ultimately rewards the good with blessings, and punishes the bad with misfortune.

The Dragon Bridge of the Great Dao is the longest handscroll among the ritual paintings of the high Yao shamans. This 167-inch-long scroll invites the full assembly of Daoist deities, sages, heavenly masters, guardians, and ancestors to descend from the spiritual realm to earth to bless the living and welcome the dead. It is used mainly at funerals, but other rituals also utilize this bridge. The Dragon Bridge is always displayed above all other paintings in various rituals. For a funeral rite, the long scroll is hung from the entry door of the house to welcome the soul of a recently deceased person into heaven. The assembly of religious administrators and deities should be viewed in descending order of rank, from right to left.

Ritual Items

Ritual instruments including rattle-daggers, seals, and printing blocks are used in services to summon spirit soldiers, ward off evil forces, and stamp inscriptions on memorials and petitions sent to the supreme Daoist gods. Many are inscribed on the back with the priests’ names.

Pan Hung is found on wands used by shamans to sanctify sacred items. Paper masks represent Daoist deities. Depending on the purpose of each ceremony, the shaman wears different masks as the earthly manifestation of the divine when he recites sacred texts, chants magical formulas, or performs a ritual dance. In addition, it is believed that by wearing other shamanic elements such as the Dragon Robe and holding a magical staff and wand, in addition to paper masks, shaman priests access powers that can exorcise evil spirits and bring peace and safety to followers.

Trian Nguyen is associate professor of Asian art history at Bates College. His most recent publication is How to Make the Universe Right: The Art of the Shaman from Vietnam and Southern China.