Pictures of an Evolution

A history of photography at the New Mexico Museum of Art

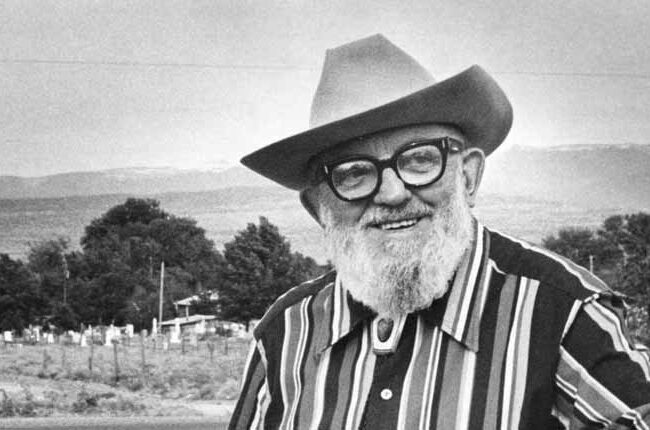

Ansel Adams, Henwar Rodakiewicz at H and M Ranch, around 1929, gelatin silver print. Collection of the New Mexico Museum of Art. Gift of Mrs. Henwar Rodakiewicz, 2003 (2003.1.1) Photo by Cameron Gay © Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust.

Ansel Adams, Henwar Rodakiewicz at H and M Ranch, around 1929, gelatin silver print. Collection of the New Mexico Museum of Art. Gift of Mrs. Henwar Rodakiewicz, 2003 (2003.1.1) Photo by Cameron Gay © Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust.

BY KATHERINE WARE

Like many significant anniversaries, the New Mexico Museum of Art’s one-hundredth birthday provides the opportunity to both share memories and look to the future. The exhibition Shifting Light: Photographic Perspectives (see sidebar), which spans the museum’s second-floor galleries, brings together classic images from the museum’s international collection of nearly 9,000 photographs, which spans the entire history of photography, with new acquisitions and promised gifts that will help define the museum’s future engagement with photographic art. The exhibition’s strong emphasis on creative innovation and viewer interpretation inaugurates the institution’s next century. But as the museum moves forward, it is useful to see where it has been. Our extensive research and preparations for the centenary have turned up new information and stories untold. The narrative is still evolving, but here, for the first time, is a story that explains how and why the museum began exhibiting and collecting photography.

From an early date, the museum adopted a progressive stance towards the relatively new medium, and photographs in its galleries occupied both supporting and starring roles. Photography’s perceived truthfulness, as well as its ability to be manipulated artistically, meant that it was flexible enough to easily fit into the founders’ evolving vision of New Mexico’s first art museum. The young museum’s commitment to contemporary art, specifically American Modernism, was surely another factor in the embrace of the medium. The discovery of photography in 1839 essentially coincided with the beginnings of European Modernism and had a strong impact on its esthetic. Though the photographs shown at the museum in the early twentieth century were not always the most vanguard examples, in New Mexico the medium found an early welcome that helped define the state as a significant locus for photographic innovation and a gathering place for the photographic community, as it remains today.

The earliest recorded solo exhibitions of photographs strongly reflect the museum founders’ interest in archeology and ethnography. Colorado native Laura Gilpin (1891–1979) was first, with a 1921 exhibition of portraits, still lifes, and Southwestern scenes. Carl Moon (1878–1948), who specialized in portraits of Native Americans, followed soon after. Both Gilpin and Moon were Anglo photographers working in the Pictorialist style, an approach that often favored soft focus and a romantic depiction of subject matter. Both, too, were passionately interested in Native culture and embarked on decades-long efforts to document it.

After graduating from an Ohio high school in 1903, Moon moved to Albuquerque to begin what became a thirty-plus-year project photographing Native Americans in the Southwest. The museum’s founders were receptive to Moon’s ambitious undertaking, aligned as it was with their own desire to foster research on Southwestern art and culture and to display artistic renderings of those subjects alongside physical examples. Moon was a talented portraitist and many of his images of individuals stand up well to contemporary scrutiny. However, his staged scenarios of Native people—with titles such as The Medicine Drum, A Tale of the Tribe, and The Dancing Lesson—now appear stilted and naïve. Like some of the work of his more well-known contemporary, Edward S. Curtis, Moon’s constructed scenes contributed to misperceptions about Native tribes and their customs. Moon’s work eventually culminated in the four-volume Indians of the Southwest, published in 1936.

Gilpin’s career-long engagement with Native peoples, particularly the Diné (Navajo), was integral to the museum’s history and its photography holdings. She began taking photographs at age twelve and when she was fourteen, her mother took Gilpin and her brother to New York City to sit for a portrait with Gertrude Käsebier, the leading female photographer of the day. In Käsebier, the young and determined Gilpin found a model and a mentor. (Later in her life, she stood on the other side of the camera to make a portrait of Käsebier.) Though she often supported herself with other work, Gilpin was committed to photography and in 1916 consulted Käsebier about where to seek formal training. Before the end of the year, Gilpin had sold her successful turkey farm for a reported $10,000 and moved east to study at the Clarence H. White School in New York City. The influenza epidemic brought Gilpin back home in 1918, but after her recovery, she opened a photography studio in Colorado Springs and became an active member of the artistic circle associated with the city’s progressive Broadmoor Art Academy.

Gilpin credits her daily visits to the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis in 1901 as marking the beginning of her interest in indigenous cultures, though surely her proximity to longstanding evidence of the Puebloan culture in southern Colorado was an influence. As Gilpin became increasingly involved with both photography and Native studies, she noticed the poor quality of images available for the study of ancient architecture of the Americas and knew she could do a better job. Always entrepreneurial, she traveled around the Southwest and in Mexico, taking photographs of the remains of Puebloan and Mayan structures. To support herself, she self-published a guidebook to Mesa Verde National Park in 1927 and assembled some of her photographs of the architecture into sets of glass slides, which she marketed for use by teachers and lecturers. Though much of her photographic work from this time can be characterized as descriptive, she also made some posed views with Native participants that are not so different from Carl Moon’s genre scenes.

For the museum, Gilpin and Moon’s hybrid images—both art and document—were useful complements to object-based exhibits; they provided context for three-dimensional objects and offered aesthetic relief from archaeologist’s drier photographs and charts. Gilpin’s own interests quickly shifted away from ancient sites as she began to have firsthand experiences with Native people, beginning her ongoing efforts to record their lives and living traditions rather than their material culture. Through her partner Elizabeth Forster, a nurse, Gilpin had the opportunity to spend time in Navajo Country over the course of several years and gained a more informed and nuanced appreciation of Diné life. In 1940, when she was finally able to publish a collection of her photographs from that series, Gilpin purposely titled her book The Enduring Navajo in response to the prevailing idea of Native Americans as a “vanishing race.”

The museum included Gilpin’s photographs in numerous exhibitions during her lifetime, tracing her development into a mature artist as well as changing ideas about photography. Her second solo show at the museum was a 1926 selection from her recent travels and included images from Mesa Verde and the Pueblos of Taos and Laguna, among others. A third solo show in 1928 featured photographs of Mayan architecture at Chichen Itzá in the Yucatán. Gilpin’s images of indigenous buildings were undoubtedly what gave her initial entrée to the museum, but her training as an artist and her growing stature as a photographer must also have made her an important advocate for photography as fine art during a time when most art institutions considered it to be merely the product of a machine.

However, throughout the 1920s, the machine aesthetic was one of the most common aspects of Modernism, and photography was perfectly suited to it. By the end of its first decade, the museum finally offered a solo exhibition of Modernist photography, a selection of work by the young American artist Henwar Rodakiewicz (1903–1976). The photographer had recently married poet Marie Tudor Garland; they lived at the H&M Ranch in Alcalde, where they entertained friends and visiting artists, including Georgia O’Keeffe and Ansel Adams (whose portraits of Rodakiewicz are in the museum’s collection). Modernism in photography stylistically shifted away from the softer Pictorialist style that Moon and, at the beginning of her career, Gilpin used. Modernist photographers, such as Rodakiewicz, embraced the camera’s precision and often rejected traditional rules about perspective and representation.

An El Palacio writer confirms that Rodakiewicz’s images were a departure from the norm, asserting, “A new note is struck” in the artist’s range of portraits, nudes, Arizona landscapes, and machine studies. The writer goes on to describe “the feeling of tension, of power and even of movement that Rodakiewicz succeeds in putting into what appear to be simple photographic studies of mechanical devices….” This account suggests a radical departure from the ethnographic and picturesque nature of photographs the institution had shown earlier, both in conjunction with objects and in the Gilpin and Moon solo exhibitions. No checklist or images from this installation remain, but the description clearly suggests that Rodakiewicz’s photographs were closely aligned with Paul Strand’s close-up studies of his Akeley motion picture camera from just a few years earlier. After the worst of the Great Depression had passed, in 1940 the museum featured Eliot Porter (1901–1990) for its next solo photography show. Just the year before, Porter, a young biochemist with a medical degree from Harvard, had achieved the distinction of exhibiting his work at Alfred Stieglitz’s New York gallery An American Place, the last photographer to do so. Around that time, Porter decided to devote himself full-time to photography and began the regular visits to New Mexico that would culminate in his moving to Tesuque. He had already begun his pioneering work in color photography, but his first show at the museum consisted of all black-and-white prints, primarily taken in Maine and New Mexico. Though Porter’s work did not become part of the museum’s collection until later, most of the images from that show, including his picture of Cañoncito Church in snow, are now part of the museum’s overall holding of more than 290 of his photographs. Both Gilpin and Porter transplanted themselves to New Mexico and grew deep roots; they became regular exhibitors at the museum, anchored the local photography community, and provided connections to the broader art world.

Throughout the museum’s first two decades, painting and sculpture were still the dominant art forms at the museum. The graphic arts (initially printmaking and drawing) were gaining in stature, however, and eventually earned a separate annual competition, starting in 1946. By 1951, the Fifth Exhibition of Graphic Arts in New Mexico included photography, and a dozen New Mexico photographers had the opportunity to show their pictures alongside the prints and drawings. The photographer Charles E. Lord of Santa Fe, though virtually unknown today, distinguished himself in a field of entries that included images by state residents Tyler Dingee, Laura Gilpin, Eliot Porter, and others. The awards committee selected Lord’s genre scene Amigos—Mexico for “first honors in photography” and also gave his photograph a purchase prize, making it one of the early photographs added to the museum’s collection. The following year, Gilpin took honors in black-and-white photography for Navajo Weaver, which the museum acquired with the Southwestern Arts and Crafts Purchase Prize. J. Hobson Bass won the prize in color photography that same year. Santa Fe artist Tyler Dingee took honors in photography in 1954 with his dramatic composition Dark Discipline, taken in the museum’s St. Francis Auditorium, and the museum added it too to the collection.

By the summer of 1956, photography had seceded from the Graphics Arts competition and the museum presented its First New Mexico Photographers Exhibition, which began an annual trend of competitions through 1959. In retrospect, it seems quite humorous that Len Sprouse’s photograph Taos Artist, a portrait of a painter holding an array of paintbrushes, received the first prize in portraiture and graced the cover of the catalog of the first photography competition. Traveling photography shows, especially those organized under the aegis of LIFE magazine, appeared at the museum on several occasions, and in 1964 the museum booked Photography in the Fine Arts, a traveling show of nationally recognized photographers organized by the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The show was clearly meant to set a high bar for photographic art, with images by nationally recognized talents Wynn Bullock, Paul Caponigro, Carl Chiarenza, Josef Karsh, Arnold Newman, and others. In 1968, the museum chose to return to the model of the New Mexico photo annual competition, but it was for the last time, and with controversial results.

For New Mexico Photographers/68, Curator William Ewing diverged from the practice of inviting local photographers to select the show and instead invited his friend Duane Michals, an up-and-coming photographer in New York, as juror. Michals’ national reputation attracted an unprecedented 260 entries from 105 photographers, including a significant number from the ranks of the growing art program at the University of New Mexico. In making his final selection of 67 prints, Michals singled out many that did not align with established ideals rules of beauty and representation.

One of that show’s reviews, which none other than Laura Gilpin wrote, bore the headline, “Photography Exhibit Found ‘Provocative.’” Gilpin found the exhibition “interesting in its seeking for new approaches, provocative in some of the results” and mentioned a “somberness” to the entries overall. “One wonders what has happened to sunlight, particularly New Mexico sunlight,” she wrote, noting the absence of portraiture, landscapes, and New Mexico subject matter. Indeed, in a statement for the exhibition press release, Michals admitted that he had chosen not many images with New Mexico subject matter. They “said nothing new or startling as photography, being merely snapshots of New Mexico,” he explained. From Gilpin’s perspective, the photographs on the walls were “interesting experiments” that belonged in a classroom rather than a museum. “This exhibit may disturb people,” Michals wrote, “because they will not see what they expect a photograph to be…but I hope that viewers will use it as a point of departure to expand their own vision of the possibilities of photography in our time.”

Gilpin’s reference to the classroom was hardly random, as many of the entrants were students in the Department of Art and Architecture at the University of New Mexico. Graduate student Jim Alinder’s untitled photograph, which Michals awarded an honorable mention, surely exemplifies Gilpin’s misgivings (directional tk). The composition is claustrophobic despite the awkward presence of two open doors, and the child’s blurred and indistinct face, along with the shadow behind, are discomfiting. The artist doesn’t offer classic beauty, balanced composition, or clear meaning, and the picture isn’t even in focus. Instead, he uses the camera and the subject to construct a psychologically intense and ambiguous scene that breaks the rules that Gilpin had learned at the Clarence H. White School.

The 1968 competition was indeed a turning point for photography at the museum. Nearly half of the photographs shown in that exhibition came into the collection, largely donated by the artists. The architect of many of the donations was another photographer in the show, Anne Noggle, who soon became the museum’s first curator of photographs. Noggle joined the museum staff on a part-time basis in 1970 after completing her M.A. degree at the University of New Mexico, the same year that Gilpin was awarded an honorary doctorate from the institution. Just as Käsebier was an important touchstone for Gilpin, so Gilpin was for Noggle (and many young photographers finding their way to New Mexico around this time). During her five-year tenure at the museum, Noggle built up the nascent collection of photographs and organized a series of groundbreaking exhibitions. The year before she left the position to concentrate on her own photography, she opened a retrospective of Gilpin’s work, a labor of love developed over several years in close partnership with the photographer William Clift, who moved to Santa Fe in 1970. Gilpin was featured, too, in the landmark show Noggle organized with Margery Mann at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Women of Photography: An Historical Survey, which came to the museum in Santa Fe in 1976.

The museum recently celebrated Noggle herself with the 2016 solo exhibition Assumed Identities, which featured selections from the museum’s holdings of nearly one hundred of her prints. Thus, at a time when photographic images on electronic screens appear to supersede photographic prints, the “provocative” work that challenged Gilpin’s sensibilities has now become historic. Generations of New Mexico photographers continue to explore photography’s capabilities in ways that have shaped the history of the medium. The museum’s collection of photographs therefore strives to reflect that adventurous spirit, which has been part of its story since—almost—the beginning.

Katherine Ware is the New Mexico Museum of Art’s third curator of photography, preceded by Steve Yates and Anne Noggle. Additional information about the history of photography at the museum is available in the exhibition Shifting Light: Photographic Perspectives.