By the Book

A traveling exhibition about Frederick Hammersley’s work on and off the canvas spends the summer at the New Mexico Museum of Art

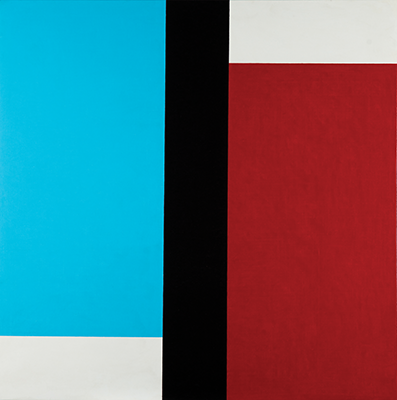

Frederick Hammersley, Adam & Eve, #2, 1970. Oil on linen on Masonite, 44 × 44 in. Collection Palm Springs Art Museum. Gift of L. J. Cella and museum purchase with funds derived from deaccession funds.

Frederick Hammersley, Adam & Eve, #2, 1970. Oil on linen on Masonite, 44 × 44 in. Collection Palm Springs Art Museum. Gift of L. J. Cella and museum purchase with funds derived from deaccession funds.

BY JAMES GLISSON

After nearly twenty years in Los Angeles, Frederick Hammersley (1919–2009) moved to Albuquerque in 1968 after accepting a teaching position at the University of New Mexico. By his own account, the move to New Mexico was the best decision he ever made. The change of location did him good, and he soon embarked on what would be his most productive decade, the 1970s.

Frederick Hammersley: To Paint without Thinking is the first exhibition to take advantage of a trove of archival materials, including notebooks, sketchbooks, and voluminous lists, to reconsider his lifelong interest in systems and rules for creating his art. While organized by The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens in California, the exhibition’s homecoming will be at the New Mexico Museum of Art (co-curated by Merry Scully) when it opens on May 26, 2018, in the state which was Hammersley’s home for fifty years. The following article is a condensed and revised version of the introduction to the exhibition catalog I edited, Frederick Hammersley: To Paint without Thinking (The Huntington, 2017), which accompanies the exhibition and is available for purchase at the Museum of Art’s bookstore.

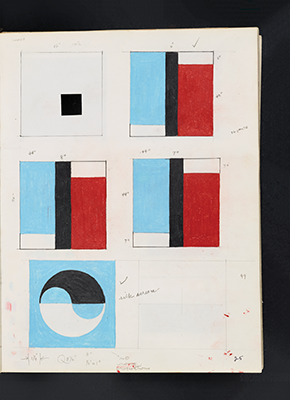

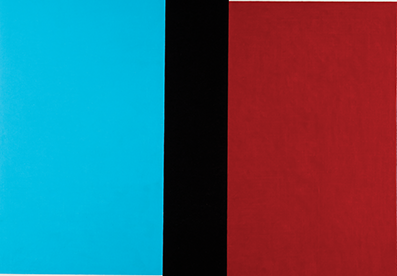

Frederick Hammersley is best known for his geometric “hard edge” paintings. Their elegant simplicity, however, is the result of a rigorous process of refinement, worked out in a set of sketchbooks and other archival materials now at the Getty Research Institute. The Notebooks, as Hammersley designated them, reveal him running through possibilities until he happened upon the solution. The page where he tests out options for the composition of Adam & Eve shows that he used the Notebooks to resolve the precise geometric composition and to establish a basic color scheme, which he returned to later as he mixed and applied paint. Although he still had to make choices as he executed the paintings, the studies in the Notebooks, like a set of instructions, largely guided him. By figuring out the big decisions before he began the paintings, Hammersley could sit down and focus on applying the paint with a palette knife to achieve his fantastically crisp edges, which he did by hand without the aid of masking tape. With the “geometrics,” as he called these paintings, he could “paint without thinking” because the thinking, so to speak, had been done in the Notebooks. The question of what to paint was settled, and he had to worry only about the how.

When I first saw the Hammersley archival material at the Getty in January 2014, I immediately wanted to organize an exhibition around it. On that afternoon I looked, in a rush, through hundreds of small lithographs, examined dozens of color swatches, leafed through the artist’s Notebooks, and passed my eyes over his sheets of titles. The sheer quantity of materials and the evident care the artist had lavished on creating and preserving them impressed on me that they were neither mere records nor material ancillary to his paintings. This exhibition is the first to highlight the archival trove Hammersley left in his home/studio at the time of his death, and to argue from its abundant evidence that the artist was profoundly concerned with the process by which he created artworks—the technical elements he used (canvas, paints, and varnishes) and the decision-making—all the choices that, little by little, bring an artwork into the world.

After a stint at Idaho State University in Pocatello, in the late 1930s, Hammersley moved to Los Angeles, where he studied at the Chouinard Art Institute. He then served in the U.S. Army during World War II, stationed first in England and later in Paris and Frankfurt. He returned to Los Angeles, where he reenrolled at Chouinard in 1946 before going on to Jepson Art Institute, studying and teaching there from 1947 to 1951. After nearly a decade of art school and the time he spent in Europe imbibing the Western artistic canon and meeting such modern masters as Constantin Brancusi and Pablo Picasso, whose studios he visited, he was ready to end his long artistic apprenticeship.

That proved difficult, however. Having completed a traditional course of study and having learned to fulfill the needs of the clients who commissioned him to do graphic design, he found the freedom of noncommercial work inhibiting rather than liberating. He was lost: “…I didn’t know what the hell to do, so I did a lot of self portraits.” As the artist recounted, he broke through this impasse with his First hunch painting on September 15, 1950. He had begun the work assuming he would produce yet another self-portrait, but something else happened. “I thought about the last element [of a self-portrait]—the eye, which in fact dictates the position of the head that supports it. I thought it would be interesting if instead, I painted that square entirely blue.” From there, he painted from square to square, choosing colors “just by feeling,” by hunch. He filled in the grid, and something clicked: “I said, ‘Boy if I can paint without thinking, that’s for me.’” Pick a color, fill in a square, repeat. This meant making fewer choices than were required to reproduce the complex geometry of a nose or hairline, and much less mixing of the paints needed to suggest the fall of a shadow or to articulate the line of a neck. He narrowed his options, set down constraints, and then, according to the rules of his game, so to speak, got on with art-making. He did not stop thinking but rather limited what he had to think about and thought about it in a different way. This breakthrough moment reverberated throughout his career.

Hammersley’s account, like any story of epiphany, elicits skepticism. He used grids to organize his compositions before his First hunch painting. In 1948, in a series of paintings, Hammersley used a step-by-step process to abstract a still life. Hammersley also used a grid format in making a set of lithographs beginning in 1949. This exhibition opens with forty-five lithographs chosen from hundreds that utilize a grid format.

What Hammersley called his Painting Books and Notebooks are key parts of this exhibition. In the late 1950s, he began keeping the Painting Books, which are essentially illustrated inventories of each step he took when he produced a painting, from stretching the canvas to applying the varnish coat at the end. These inventories, which specify the formulas the artist used for the mixtures of ground, paint, and varnish, are a boon to the co-curator of this exhibition, Alan Phenix, a scientist at the Getty Conservation Institute, who examines the intricacies of the painting process as well as Hammersley’s fastidious attention to his materials. In the Notebooks, he tweaked compositions for his geometric paintings in a two-step process. First, he tried out compositions, generally with color pencil, although ballpoint pen, black electrical tape, and oil paint appear, too. Then, often in oil, he enlarged those he found satisfactory in “composition books.” Finally, from those oil-on-paper studies, he chose compositions to enlarge further on canvas. From the mid-1960s to 1996, when he stopped making geometrics, these studies were a wellspring, and the tinkering and refinements in them bring to light the labor hidden by the serene finished canvases.

In 1968, when Hammersley moved to Albuquerque, New Mexico, he seized the opportunity to learn the computer program ART 1 and made what he dubbed “computer drawings.” Though hardly user-friendly by today’s standards, the program was among the first designed for visual artists without coding skills. In the late 1960s, when Richard Williams, the UNM faculty engineer who invented ART 1 in collaboration with Katherine Nash, explained that the program “does not require a computer programmer to hold the artist’s hand,” computers were still the province of highly trained scientists at universities and government research facilities. Although Hammersley’s excursion into computer art did not change the look of his geometric paintings, his documentation of their production became far more complete. Indeed, starting in the 1970s, the Painting Books break down a painting’s creation into a series of steps, with dated entries for each and details of every application of paint as well as the paint mixture applied. A computer program is nothing more than a set of instructions, and as the artist struggled to master the complex protocols of ART 1, perhaps he began to regard the process of paintings as following a set of instructions, like those on the punch cards fed into the IBM mainframe that printed the drawings. As this exhibition catalog excerpt suggests, the apparent simplicity of Hammersley’s abstract art belies a complicated creative process. His art was not a spontaneous, all-at-once act, but the outcome of a systematic approach that allowed him to “paint without thinking.” By this phrase, he did not mean becoming a machine, but working within constraints. Like chess, with its inflexible rules but vast number of possible games, Hammersley’s art is one of variations and play within boundaries.

James Glisson is the Bradford and Christine Mishler Associate Curator of American Art at The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. He and Alan Phenix, a recently retired scientist at the Getty Conservation Institute, were the co-curators of the exhibition at the Huntington.