Straight Back to Our Own Country

How a Navajo shaman negotiated with one of America’s most legendary generals for his tribe’s survival

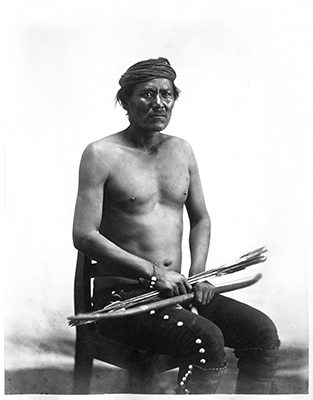

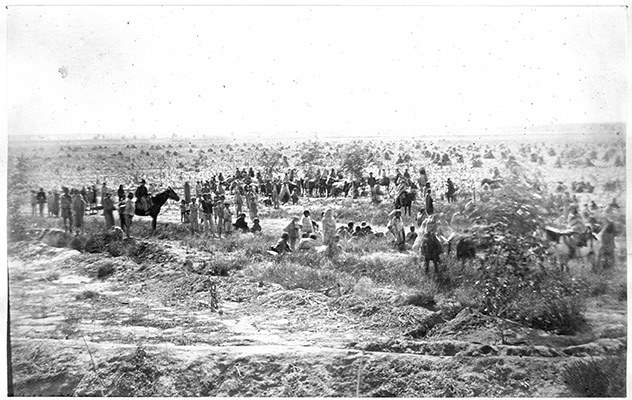

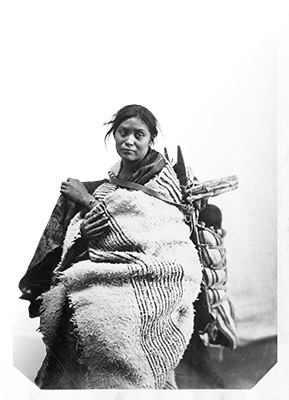

Navajo Indian captives under guard at Fort Sumner, New Mexico, ca. 1864–1868. Courtesy Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA), Neg. No. 028534.

Navajo Indian captives under guard at Fort Sumner, New Mexico, ca. 1864–1868. Courtesy Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA), Neg. No. 028534.

BY HAMPTON SIDES

This story accompanies Esther G. Belin’s poem, “The Petition(-ing, er) of Peace(-ful)(mak -ing, -er).”

At the War Department, Kit Carson met with generals Phil Sheridan and William Sherman. Sherman was preparing to travel west as part of a special commission to make treaties with numerous tribes. Among other ambitious projects, he and his fellow commissioners would be visiting New Mexico to consider closing down Bosque Redondo. During their visit in Washington, Sherman in all likelihood discussed the Navajo predicament with Carson.

There is some evidence that Carson had slowly come to recognize the massive failure of the Bosque. Having now successfully created a reservation for the Utes in their own homeland, perhaps Carson had come to see the wisdom of allowing the Navajos to return to their native country as well.

On a bright morning in late May, the same week that Kit Carson died, several thousand Diné gathered on the plains of Bosque Redondo, away from the Pecos, out on the hard, bright ground where they could all see one another. A chant rose up from their midst, a song that slowly built on itself as the collective energy took hold. Then, the Navajos began to clack stones together, and a clear pulse ran through the tribe.

The sound of the clicking rocks puzzled the soldiers over at Fort Sumner. At first they feared it was the first stirrings of an insurrection, and they climbed to the rooftops of the Issue House to investigate.

The Navajos had formed a circle several miles in diameter, so large that any person standing on the circumference could look across the plains and see only tiny human dots on the circle’s opposite side. Then, taking small, measured steps, they began to close the ring. As they stepped forward, the Navajos continued to chant and clack their rocks. Slowly, the circle began to shrink on the plain, tightening like a great noose.

In the center, a young coyote stood up and began to run in fright. As the circle closed up, the coyote ran frantically this way and that, until it finally understood it had nowhere to go: It was trapped inside a human corral.

Whether out of sheer terror or an instinct to feign death, the coyote lay down. Then Barboncito, the small, bearded medicine man from Canyon de Chelly, stepped inside the circle and approached the trembling animal. Several others helped him hold the coyote down. Barboncito opened his medicine bag and removed a bead of abalone shell. Carefully, he placed the white bead in the coyote’s mouth and began to pray over the animal.

The chanting and the percussion of the rocks stopped, and in the silence, each person on the circumference slowly backpedaled: The great noose was opening up again.

Barboncito was keen to see in which direction the coyote would run. That was the purpose of the ceremony, in fact. It was an ancient ritual, one that Navajo medicine men performed only in extreme circumstances, to look for signs that concerned the future of the tribe.

Suddenly Barboncito and the others pulled away, and the coyote sprang up. It looked confused at first. And then it turned in the direction Barboncito had hoped. The coyote bolted across the thickets of cholla and mesquite, and escaped from the confines of the human circle.

It was running headlong toward the west.

A few days later, on May 28, 1868, General William Sherman arrived at Bosque Redondo with his entourage from the Great Peace Commission. He must have known that his friend Kit Carson had died five days earlier. Sherman understood that with Carson’s passing, an era had ended and a new one had begun. Carson helped to put the Navajos here, and now Sherman had the authority to undo what his friend had done. Sherman was no softhearted advocate for the Indians, but he could see that the reservation was an abject failure, that the Navajos were despondent and the farms fallow. “I found the Bosque a mere spot of grass in the midst of a wild desert,” he later wrote, “and that the Navajos had sunk into a condition of absolute poverty and despair.”

General Sherman joined the other members of the commission in one of the buildings on the grounds of Bosque Redondo. There they met a small delegation of Navajo headmen, led by Barboncito and Manuelito. Two Spanish interpreters translated the proceedings, and army stenographers recorded everything.

General Sherman rose and spoke first. “The Commissioners are here now for the purpose of learning all about your condition. General Carleton removed you here for the purpose of making you agriculturalists. But we find you have no farms, no herds, and are now as poor as you were four years ago. We want to know what you have done in the past and what you think about your reservation here.”

Barboncito stood up to answer for the Navajos. He had great poise, a calmness at the center of his being. But an unmistakable passion also rose from his words and gestures.

“We have been living here five winters,” he said. “The first year we planted corn. It yielded a good crop, but a worm got in the corn and destroyed nearly all of it. The second year the same. The third year it grew about two feet high when a hailstorm completely destroyed all of it. For that reason none of us has attempted to put in seed this year. I think now it is true what my forefathers told me about crossing the line of my own country. We know this land does not like us. It seems that whatever we do here causes death.”

Barboncito then explained to Sherman his aversion to the prospect of moving to a new reservation in Oklahoma. “Our grandfathers had no idea of living in any other country except our own, and I do not think it right for us to do so. I hope to God you will not ask me to go to any other country except my own. This hope goes in at my feet and out at my mouth as I am speaking to you.”

Sherman was visibly touched by Barboncito’s words. “I have listened to what you have said of your people, and I believe you have told the truth. All people love the country where they were born and raised. We want to do what is right. We have got a map here which if Barboncito can understand, I would like to show him a few points on.” It was a map of Navajo country, showing the four sacred mountains and other landmarks Barboncito immediately recognized.

Sherman continued, “If we agree, we will make a boundary line outside of which you must not go except for the purpose of trading. You must know exactly where you belong. And you must not fight anymore. The Army will do the fighting. You must live at peace.”

Barboncito tried to contain his joy but could not. The tears spilled down over his mustache. “I am very well pleased with what you have said,” he told Sherman, “and we are willing to abide by whatever orders are issued to us.”

He told Sherman that he had already sewn a new pair of moccasins for the walk home. “We do not want to go to the right or left,” he said, “but straight back to our own country!”

A few days later, on June 1, a treaty was drawn up. The Navajos agreed to live on a new reservation whose borders were considerably smaller than their traditional lands, with all four of the sacred mountains outside the reservation line. Still, it was a vast domain, nearly twenty-five thousand square miles, an area nearly the size of the state of Ohio. After Barboncito, Manuelito, and the other headmen left their X marks on the treaty, Sherman told the Navajos they were free to go home.

June 18 was set as the departure date. The Navajos would have an army escort to feed and protect them. But some of them were so restless to get started that the night before they were to leave, they hiked ten miles in the direction of home, and then circled back to camp—they were so giddy with excitement they couldn’t help themselves.

The next morning the trek began. In yet another mass exodus, this one voluntary and joyful, the entire Navajo Nation began marching the nearly four hundred miles toward home. The straggle of exiles spread out over ten miles. Somewhere in the midst of it walked Barboncito, wearing his new moccasins.

When they reached the Rio Grande and saw Blue Bead Mountain for the first time, the Navajos fell to their knees and wept. As Manuelito put it, “We wondered if it was our mountain, and we felt like talking to the ground, we loved it so.”

They continued marching in the direction the coyote had run, toward the country they had told their young children so much about. And as they marched, they chanted—

Beauty before us

Beauty behind us

Beauty around us

In beauty we walk

It is finished in beauty

Hampton Sides is an American historian, author, and journalist. This excerpt from Blood and Thunder was reprinted with the author’s permission. Sides’ account of the discussion between Sherman and Barboncito is taken from United States, Proceedings of the Great Peace Commission of 1867–1868.