The Science behind Frederick Hammersley’s Modern Art

Frederick Hammersley, Open, #3, 1950. Lithograph in artist-made frame, 3 × 3 in. (frame: 8 × 8 in.), Frederick Hammersley Foundation. One of the artist’s series of late-1940s 3-inch lithographs based on tic-tac-toe squares

Frederick Hammersley, Open, #3, 1950. Lithograph in artist-made frame, 3 × 3 in. (frame: 8 × 8 in.), Frederick Hammersley Foundation. One of the artist’s series of late-1940s 3-inch lithographs based on tic-tac-toe squares

BY JOSEPH TRAUGOTT

I met Frederick Hammersley in the early 1980s. We bonded quickly around our shared penchant for making bad puns in public, and never apologizing to those who suffered from them. After making a particularly obnoxious pun, Hammersley would respond after a long pause, “Yes . . . okay.” Our friendship lasted until his death in 2009.

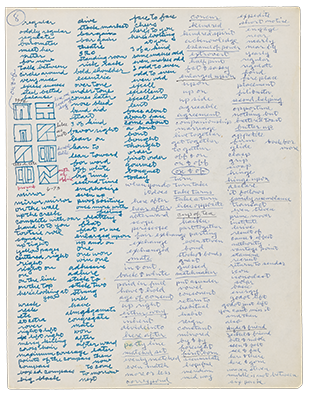

Puns dominate the titles he chose for many of his works, such as his computer drawing DO YOU Z (a play on the words “Do you see.”). He kept lists of words and phrases that could describe the actions of the forms in his art. Often Hammersley included small sketches of pieces alongside potential titles to keep the image in front of him as he freely associated words and images. When a phrase worked with a specific piece, he circled it, or underlined others. The freewheeling exchange with himself in one section (see first column below drawings on page 63) goes “mirror / mirror mirror / on the wall / complete with our / hand is to you / tootsie roll / square / uptight / yellow pages . . . .”

I’ve written about the range of Hammersley’s images, and curated the breadth of his artmaking in Visual Puns and Hard-Edge Poems: Works by Frederick Hammersley (Museum of Fine Art, Museum of New Mexico, 1999), but I never got it quite right, until now. I never understood he was tipping his hat to science, not art, with his compulsive activities. Hammersley fused together three seemingly contradictory aesthetic approaches in his studio: 1) He used science-like controlled experimentation to clarify ideas; 2) He then foiled them with his freewheeling “hunch” paintings, and 3) He finally emphasized his Modernist outlooks by enclosing his smaller works with funky frames that feign a lack of sophistication.

Perhaps his pseudo-scientific approach jelled in the late 1940s when Hammersley taught himself to make lithographs, no mean feat. He printed an extended series of three-inch square images that explored the nature of modernist compositional ideas he discovered while a soldier in Europe at the end of World War II.

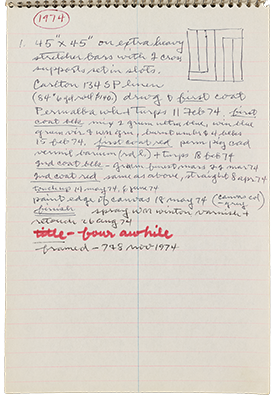

Hammersley’s notes foil the freewheeling title pages that act like free verse. But the compulsion in his written notes allowed him to repeat materials and images, and reject events that were unsatisfactory, just like a scientist. His note from a stenographer’s pad makes this point as he described Four awhile, a large square oil painting from 1974 with a punny title.

After his meticulous production of experimental lithographs during the late 1940s, Hammersley moved in the opposite direction: his hunch drawings and paintings. With these works, he would draw a line or paint a shape in color, and then wait for a hunch before making the next move. In some ways Hammersley’s hunch paintings were like playing chess with himself. Sometime his hunch worked well, and other times the next element had to correct a previous mistake.

Hammersley continuously flipped between science and his intuition, both based on years of visual thinking: small scientific lithographs, large hunch paintings, large geometric works noted for their pristine “hard edges,” organic paintings that moved from hunch to hunch, a series of computer drawings created through punch cards directing a mainframe computer, and then back to the hunches with a long series of small organic works.

You may have already noted Hammersley’s unusual frames; they look like something an outsider artist might make from found objects. Aesthetically, these handmade frames were diametrically opposed to his sophisticated imagery. But this unique synthesis made his jewel-like small prints, paintings, and photographs sing in a harmony that is difficult to realize. An incredible achievement. Or as Hammersley would say, “Yes, okay. . . . Marrrvelous.”

Joseph Traugott is the former curator of twentieth-century art at New Mexico Museum of Art, and a member of the Frederick Hammersley Foundation board of directors.