Gone but Not Conquered

Standing Rock changed the way this country thinks about Indigenous sovereignty and resistance. What’s next?

Catcher Cuts The Rope (Aoanii, Nakota), a Marine injured in Fallujah, leads a two-mile walk protesting the Dakota Access Pipeline, which will cut across several sacred Indigenous sites and tunnel under Lake Oahe, which feeds into the Missouri River. Photograph by Alyssa Schukar.

Catcher Cuts The Rope (Aoanii, Nakota), a Marine injured in Fallujah, leads a two-mile walk protesting the Dakota Access Pipeline, which will cut across several sacred Indigenous sites and tunnel under Lake Oahe, which feeds into the Missouri River. Photograph by Alyssa Schukar.

BY C.L. KIEFFER AND DEVORAH ROMANEK

Most exhibits take years to plan, which is antithetical for museums that aim to be responsive to issues of contemporary urgency in today’s technologically-driven world. Take the issue of the protests at Standing Rock. The political urgency of the movement, its rapid proliferation, and associated social media phenomenon inspired us (Museum of Indian Arts and Culture curator C.L. Kieffer Nail and Maxwell Museum of Anthropology curator Devorah Romanek) to curate Beyond Standing Rock, at MIAC (February 23 through October 27). In order to create a rapid response exhibit, we asked individuals posting related videos and photographs on social media if we could include these materials in the exhibition.

Plans for the 1,172-mile-long Dakota Access Pipeline, which would run from North Dakota to Illinois, became public in June of 2014. Construction began in June of 2016. With the project’s construction, Dakota Access LCC (a subsidiary of Energy Transfer Partners, L.P.) promised that the building of the pipeline would provide the local communities with a number of permanent jobs, thousands of temporary jobs, and tens of millions in tax revenues. The pipeline project encountered major backlash when the original route, which would have traveled just north of Bismarck, North Dakota, was moved further south to cross the Missouri River due to the threat of contaminating Bismarck’s water supply. The new route would cross multiple states, communities, farms, fragile wildlife habitats, and tribal lands.

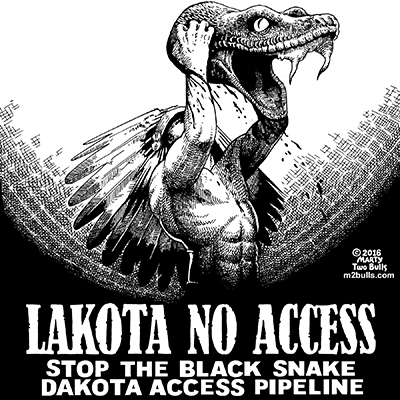

The Sioux (O˘chéthi Šakówi), an Indigenous nation comprising the Lakota, Nakota and Dakota, protested that this route threatened their water supply from the Missouri River and Lake Ohae. They also contended that the land the new route proposed to cross was seized in violation of the 1851 Fort Laramie treaty between the United States and the Sioux, and that the new route threatened to damage or destroy significant historic, cultural, and religious sites that were not initially reported by the US Army Corps of Engineers in their limited assessment of the area.

Protests against the pipeline began in early 2016 at Standing Rock Reservation with the establishment of Sacred Stone camp on the property of LaDonna Brave Bull Allard, a Lakota historian. These initial protests quickly expanded beyond members of the Sioux Nation to include individuals from over one hundred Indigenous tribes and nations, as well as non-Indigenous Americans, as protesters shared their experiences on social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter. The activists did not have to hope that mainstream journalists would expose their plight; they were able to cut out an unreliable middle man by posting instant updates and live reports. Social media also enabled its participants to plan, organize, fundraise, and acquire needed supplies for the growing movement. On February 23, 2016, after a number of confrontations between water protectors and local authorities, the National Guard and local authorities evicted the last of the protesters, arresting anyone who refused to leave.

The first iteration of this exhibition, Entering Standing Rock: The Protest Against the Dakota Access Pipeline, opened at the Maxwell Museum in Albuquerque on March 25, 2017, just a little over a month after President Donald Trump approved the completion of the pipeline. That exhibition ran until March 10, 2018, and informed visitors in real time about the ongoing protests against the project while construction was underway, its completion on June 1, 2017, and its first oil leaks and spills in November of 2017.

Two years after the protests were forcibly halted, MIAC has the privilege to expand upon the original exhibition with Beyond Standing Rock. In addition to showing the work of photographers, graphic artists, musicians, activists, and organizations featured in the Maxwell Museum exhibition, Beyond Standing Rock will also include new artwork inspired by the events that happened there, and highlight other prevailing and new environmental issues that face Native American tribes today.

C.L. Kieffer Nail is the collections manager for the Archaeological Research Collection at the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture. Devorah Romanek is the curator of exhibits at the Maxwell Museum of Anthropology in Albuquerque.