Petal Pusher

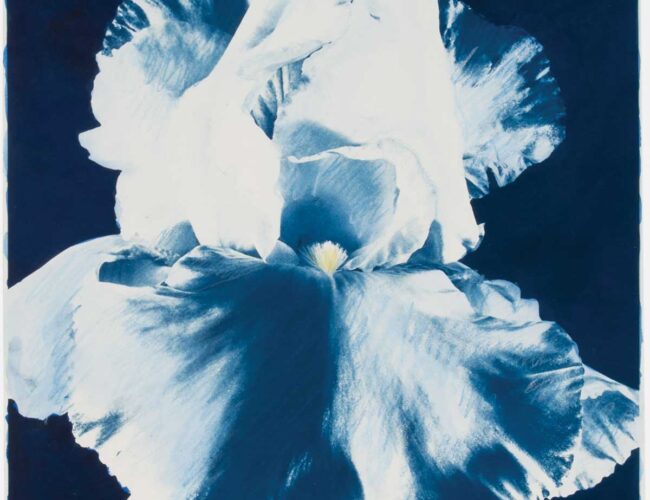

Betty Hahn, Large Blue Iris, 1985. Hand-colored cyanotype. 19 3/8 × 15 5/8 in. Collection of the New Mexico Museum of Art. Gift of the Roberta DeGolyer Estate, 1995 (1995.33.18).

Betty Hahn, Large Blue Iris, 1985. Hand-colored cyanotype. 19 3/8 × 15 5/8 in. Collection of the New Mexico Museum of Art. Gift of the Roberta DeGolyer Estate, 1995 (1995.33.18).

BY KATHERINE WARE

It’s spring, and our fancy turns to flowers. For those who are not the gardening sort, or for anyone impatiently awaiting a hint of new growth, we present this frilly, exuberant iris by artist Betty Hahn. The mythology of the iris dates to ancient Greece, where the personification of the goddess Iris was a rainbow, symbolizing her role as a link between heaven and earth. Legend has it that purple irises were planted on the graves of women to call the goddess to guide them to heaven. The iris gets its heavenly hues from the cyanotype photographic process, which uses iron salts to generate this distinctive Prussian blue.

Originally from Chicago, Hahn spent part of her career in Rochester, New York, before moving to Albuquerque to join an all-star cast of teachers in the Department of Art and Architecture at the University of New Mexico. Hahn’s innovative work is well-represented in the Museum of Art’s collection, with more than 75 examples from across her career. The title of her 1995 solo show and book at the New Mexico Museum of Art, Photography or Maybe Not, suitably conveys Hahn’s reputation as a photographic genre-bender. She is known for using some of the medium’s oldest processes, such as this cyanotype. She is also known for enhancing her prints with pastels, paint, and even embroidery.

So why is such a photo rebel photographing flowers? As the Women’s Liberation Movement developed in the 1960s and 1970s, some women artists began adopting subjects and techniques traditionally associated with women that were considered less important than painting and sculpture. Perhaps the most renowned example is Judy Chicago’s mixed-media installation The Dinner Party (1979), which celebrated the female body using china painting and embroidery. In Rochester, home of Kodak and the George Eastman House’s famous collection of film and photographs, many photo-centric female artists were already working with mixed-media and books. It was a short step to incorporating everything from needle and thread to the newly developed Xerox machine. Many women also chose to concentrate on personal and domestic subjects such as family, female sexuality, and identity issues.

Hahn’s flower, though made later, fits nicely into that rich socio-artistic milieu. When asked to consider this evaluation of her longstanding interest in flowers as a subject, Hahn had an even better explanation: “I really like flowers.”

Katherine Ware is the curator of photography at the New Mexico Museum of Art.