A Beautiful Death on the Santa Fe Trail

By Frances Levine, Ph.D.

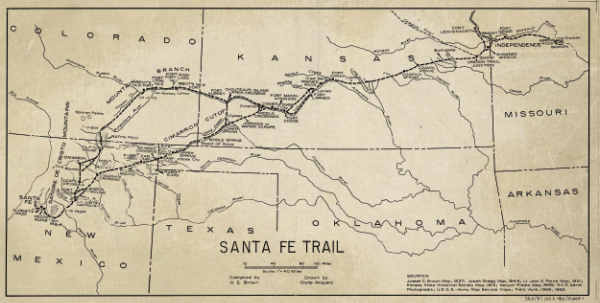

Travel on the Santa Fe Trail was not restricted to the hale and hearty. Some travelers made the strenuous journey to try to reclaim their health. Many travelers—men and women—wrote diary entries remarking about their increasingly robust constitution that seemed to come from the pure air and sunshine of the best days on the trail and their connection with nature that came from sleeping under the stars. Others wrote about the discomfort of the trail and the challenges that accompanied them on their crossing, yet hoped the journey would improve their health. The trail from St. Louis to Santa Fe and the return from the Southwest to the States was not without risks and dangers, and even death lurked on the prairie.

The story of Kate Messervy Kingsbury, who died on the Santa Fe Trail in June 1857, is especially poignant. Kate made three trips across the trail between 1854 and 1857. As her husband, veteran trail merchant John M. Kingsbury, planned each trip from her home in Salem, Massachusetts, to supply houses in St. Louis, and then on to Santa Fe or the reverse direction, he feared that any one of those journeys might end her life.

Described by her family as a genteel and fragile beauty, Kate was the sister of William Sluman Messervy, a well-regarded merchant. He moved from Salem to St. Louis in 1834; in 1839, when he joined as a junior partner in the mercantile firm of James Josiah Webb, Messervy opened their store in Santa Fe. With suppliers in New England and St. Louis, Webb and Messervy followed a competitive and lucrative business practice that wholesaled fabrics, groceries, housewares, and hardware obtained in northern markets, aggregated them in Missouri supply centers, and carted them across the heartland of the continent for the Santa Fe trade.

John M. Kingsbury, a Boston bookkeeper, joined the firm in Boston in 1849 and was mentored into the trade by Webb and Messervy. Kingsbury traveled between St. Louis and Santa Fe for the firm in 1851, and by 1854 he joined the firm as a junior partner, handling their business transactions in Santa Fe. Webb, Messervy, and Kingsbury each prospered financially, but all suffered personal losses and economic strains that ultimately led to their abandoning the Santa Fe trade.

Messervy began to withdraw from the business after 1853, and left New Mexico in 1854. Kingsbury furthered his importance to the partnership after he married Messervy’s sister Kate on December 21, 1853. Kingsbury was the last of the partners to live in Santa Fe, where he spent the majority of his time between 1853 and 1861.

When Kate married John M. Kingsbury, she had already been diagnosed with the early symptoms of tuberculosis, or consumption as it was called then. It was a disease that struck many people in the crowded, often unsanitary cities of the United States in the nineteenth century. One prescribed therapy for the disease that persisted well into the early twentieth century was a regimen of travel to more healthful climates, where fresh air and rest supposedly provided much of the cure.

Her brother and her husband feared that she might not be strong enough to travel to Santa Fe. But it was that very journey that offered her the last and best hope for recovery. Kate Messervy Kingsbury may never have enjoyed any of her three crossings of the Santa Fe Trail, but she left no personal record of her feelings or fears. In correspondence between Kingsbury and his partner Webb and with his brother-in-law and partner Messervy, the progression of Kate’s illness is discernable, and Kingsbury’s own emotional turmoil is evident.

Consumption Causes and Cures in the Nineteenth Century

Permit me to give [a recipe] for producing consumption. Take a girl between the age of twelve and eighteen, who is growing rapidly, of delicate constitution; confine her six hours each day in a crowded school-room; let her have lessons to get out of school which will require from two to three hours of study, in addition to two hours’ practice on the piano-forte; stimulate her to extra exertion by hope of a prize at the end of the term, or of excelling her classmates; let her sleep in a dark, close and small bedroom, with one or more persons; supply her plentifully with candy and sweet-meats, so as to destroy any little appetite she may have for wholesome and nourishing food; when out of school, confine her to a heated room, except occasionally going to church or to parties in thin stockings and shoes, and low dress, so as to expose the chest and neck to the cold—and you have all the requisites to produced disease. Should you not produce consumption, you will be likely to have disease of the brain, equally but more quickly fatal.

–Professor C.B. Coventry, 1856

Tuberculosis, known in nineteenth century literature as consumption or by its more technical name phthisis, was widespread throughout the world. Discussions of what caused the disease and how to cure it ranged from the scientific to the spurious, from practical and healthful to utter quackery. Antibiotics would prove to be the only cure, but nineteenth-century doctors and their patients experimented with cod liver oil, sugar vapor, and inhaled iodine and an inhalation made with creosote for short-term relief.

Professor Coventry’s description of the social conditions and lifestyle stresses that could give rise to consumption refers to some of the common ways in which consumption was thought to have been contracted in the early nineteenth century. It was not until 1882 that the bacteria responsible for the spread of TB was identified by a German microbiologist. When rest and recuperation were not enough to halt the disease, its progression was marked by specific symptoms.

Dr. James Clark published one of the many sources offering a comprehensive consideration of the course of TB in 1835. In its first stages, consumption could be diagnosed by its persistent cough and fatigue. Gradually, the patient might experience night sweats and chills, and some loss of muscle firmness. There could be a seasonal aspect to the disease’s progress as well. If a patient first experienced symptoms in the spring, the onset of warmer weather and the opportunity for outdoor activities could slow or even arrest the disease. If the patient contracted the disease in winter, Dr. Clark thought there was little chance it would subside.

The second stage of consumption was marked by a frothy, sometimes bloody, but always a productive cough, as well as a marked rasp or crackling in the lungs. Bouts of fever and chills increased, and the patient began to experience pain in their chest and shoulders as the lungs “softened.” Dr. Clark noted that some people persevered with the symptoms for months and even years, while others arrived “at the brink of the grave” within weeks. In the third stage of the disease, patients had frequent attacks of chills and fever, diarrhea, and of course the deepening and prolonged coughing. By this stage they also experienced a marked change in posture and body appearance as their shoulders raised and stooped forward, forming a more concave upper chest. Dr. Clark noted that patients had diminished physical and mental energy, and could appear to be “skeletal.” In their final days, patients became delirious, and often violently so. Dr. Clark concluded with a rather telling summary of how consumption impacted the emotional state of the patient:

…[T]hat inward struggle between hope and fear, which, whether avowed or not is generally felt by the patient in the latter stages—constitute a degree of suffering which, considering the protracted period of its duration, is seldom surpassed in any other disease.

Bound for Santa Fe—A New Western Frontier

John Kingsbury was 22 years old when he first journeyed to New Mexico in 1851 as a clerk and bookkeeper for Messervy and Webb. He served for a time as well as a private secretary to William Carr Lane, the second territorial governor of New Mexico. Kingsbury was known as a careful bookkeeper with fine penmanship, good organizational and personal skills, and was “proficient with numbers as well as guns,” according to the firm’s biographers.

While Kingsbury attended to the trade, Messervy became involved with political affairs, serving as a delegate to Congress from the newly recognized Territory of New Mexico. Messervy was never seated in Washington, but did serve in Santa Fe as secretary of the territory, and then as acting governor during the administration of David Meriwether (1853 to 1855). When Messervy decided to leave the trade, Kingsbury and Webb then formed a new partnership.

John Kingsbury and Webb returned to New England in the fall of 1853, both determined to find wives. They kept up their correspondence with each other, sometimes playful and sometimes seriously trying to reassure each other of the arrangements that might make for continued success in the Santa Fe business, provided they could find wives ready to join them. Each would marry before the end of the year.

When Webb visited the Messervys in Salem in early October 1853, he wrote a long letter to Kingsbury, who was then on a supply trip to St. Louis, mentioning that he saw Kate, the “original” of the photo John had carried in New Mexico. William Messervy writes to Webb as well, urging him to influence Kingsbury to resume his courtship with Kate, but also to buy out Messervy’s share of the Santa Fe business. Messervy is anxious to return to Salem so that he can rejoin his own family there. Kingsbury and Kate seemed uncertain about marrying, though it is not clear if this is due to Kate’s illness, her strong bond with her mother and sister in Salem, or the dangers of living in New Mexico—though all are certainly mentioned in correspondence between Kingsbury and Webb. Webb writes:

I spent but a short time in Salem, and had but little time to see the gals, but made the most of my time in talking with, and looking at, the original of the picture you value so highly. I talked much of New Mexico, and much of her going out there provided you desired her to do so. I think she would go, but her sister and Mrs. Messervy have the greatest horror of that country, and the strongest attachments to home of any two persons I ever met. I told her (as I really thought and still think) she ought by all means to go there in preference to remaining in this country, even with pecuniary prospects equal. Her health is very delicate and I can but believe that the trip and a residence of a few years in that country would establish her health upon a strong constitution. I told her of the proposals I had made you and Mr. Messervy, that I was willing to take you in an equal partner, whether we continued the business, or he should withdraw from the concern. This I desire to do.

On December 2, Kingsbury and Kate Messervy were married in Salem. They honeymooned in New York, where they met up with James Webb and his new wife Florilla “Lillie” Mansfield Slade. Webb and Kingsbury, the new partnership, used their respective honeymoons to buy supplies for the Santa Fe trade. They bought cloth and clothing, shoes and boots, alcohol, and hardware. They sought markets to receive beaver pelts, wools, and minerals from New Mexico.

At the end of February 1854, there still seemed to be some question about when Webb, Kingsbury, and their brides would return to New Mexico. Writing to Kingsbury from Santa Fe, William Messervy chided his new brother-in-law for taking so long to make up his mind about his business offer, and whether he would bring Kate and her sister Eliza Ann with them to New Mexico. He scolded his partners for being unprepared for their wives to begin life New Mexico, but he was also clearly pleased that they were returning to the West, and that Kate’s health was improving since the wedding.

I was much pleased to learn that you and Kate had so fine a wedding and that Kate’s health is improving. I have no doubt she will experience great benefit from her trip to this country, that is if she comes. I am most anxious about my sisters and am completely in the dark to know even where to write to them. You have managed this thing very badly. You should have made up your minds either to stay or come as long as the first of January.…

If my sisters are with you I must depend upon you and Mr. Webb to do the best you can to promote their comfort. Give Eliza Ann, if she is with you, all she wants. It is too late now for me to make arrangements….

I wish you and Webb would think a little about what you are going to do when you get out here. You both remind me of two boys who have found birds’ nests and think the whole world is in them. Would it not be well to give a thought as to where you are to live when you get out here—or do you intend to tumble in here with the whole crowd who come in at the same time with you….

Over the years Messervy continued to advise Kingsbury from afar, and it is through their family connections and lengthy correspondence that we learn the most about the progression of Kate’s health and other personal details.

Messervy was solicitous yet directive in business matters in his correspondence with Kingsbury. Later, his letters have a strong tone of censure when he describes what he sees as Kate’s failures as a wife and an upstanding Christian woman when she pities herself for her illness and the undisclosed deformity and illness of her only child. (Kingsbury’s letters written during his time in Santa Fe, meanwhile, are focused largely on the business climate and the difficulties he encounters in placing and receiving orders. His letters also contain warm fraternal feelings for both Webb and Messervy. As Kate’s condition worsens, his letters reflect his fears and his hopes, his frustration and his devotion.)

There is little in the surviving correspondence about the trip that these two newly wedded couples made together across the Santa Fe Trail in 1854. Webb writes to Kingsbury on March 7, urging them to set a date to begin their return, noting that they will need three weeks in Independence to gather the goods they have bought in New York, Philadelphia, and St. Louis. In mid-March they began their journey. At the end of March, Messervy wrote to Webb urging them to exercise caution as bands of the Jicarilla Apaches and Utahs (Utes) lately had been increasing their attacks on wagons and the U.S. Army.

They shipped items first by rail from New York to Pittsburgh, and then from there to St. Louis on the Granite State Steamship. Then on April 11 they were in St. Louis purchasing wholesale groceries from the Glasgow Brothers. They bought boxes of soaps and candies, condiments and cordage, sugar, tobacco, and whiskey, all totaling just over $2,100.00 in value. On April 17 they purchased an assortment of plates, lamp glass chimneys and globes, canisters, and housewares from E.A. & S.R. Filley on Main Street in St. Louis. And on that same day they purchased a few chairs and tables, a camp bedstead, bolsters, cotton batting, pillows, and mattresses. Some of the items no doubt they used to make comfortable camps on the trail, and others were likely furnishings for their new homes in Santa Fe.

By the end of April, Messervy was anxiously awaiting the reunion he would have with his partners and Kate. He wrote to Kingsbury that he would “give a dollar an hour if you and Webb were only here—it would take a great load off my shoulders.”

They arrived in Santa Fe in June 1854 to begin their new life.

The Webbs’ and Kingsburys’ Santa Fe Experience

As the Webbs and Kingsburys established themselves in Santa Fe, William Messervy withdrew from the business and his political life. He resigned as Secretary of New Mexico Territory in July 1854, then sold his house fronting the Santa Fe Plaza to the two couples. Messervy returned to Salem, but stayed in correspondence with both couples.

Santa Fe was not so impressive to those who arrived in the nineteenth century. Webb, Messervy, and Kingsbury entered New Mexico as it was transitioning from a military occupation to an administrative territory of the United States. They were joined too by Archbishop Jean Baptiste Lamy, who brought a French Catholic perspective and style to the church that was a departure for centuries-old Hispanic practices and local traditions.

Santa Fe and the Territory of New Mexico in the 1850s were divided by political allegiance, religious and family alignments, and feuds. It was a time punctuated by rising disagreements among territorial governing authorities who had little experience with local customs, not to mention politicians and political processes that were not understood by these newly arrived officials. The military and the growing Anglo-American population differed over how to deal effectively with raids by nomadic Indian groups. There was insufficient funding for the government, and the imposition of new laws, norms, and language on the population made solving any issue fraught.

Merchants had the hard cash, so that even the territorial governors had to issue warrants to support the new government. The solvency of the territorial government and the stress it put on the merchants is a recurring theme in Kingsbury and Webb’s correspondence. Their letters are filled with political intrigues and business details. Unfortunately, none of the letters that Kate or Lillie wrote have been found, and so they are remembered only in passing comments in others’ correspondence about their lives in Santa Fe.

By summer, Kate and Lillie’s advancing pregnancies must have been evident—though none of said letters mention it. Lillie Webb gave birth to a son on December 22, 1854, and Kate to her son George in January 1855.

What should have been a joyous event for the Kingsburys was apparently not, although John Kingsbury’s letter on the subject in which he confided his worries to his brother-in-law was evidently destroyed. William Messervy wrote to John on March 13, responding to his letter of February 1, 1855. Messervy assured Kingsbury that he had burned the letter informing him of the birth of their son who was somehow deformed and might not survive. Messervy promised that he had told no one of the birth of the child. He counseled John from his own experience with a child who was not “perfect” that, should the child survive, he was sure that Kate and John would come to love the child and would in their Christian kindness extend that extra care that the child might need.

Kate’s despair only deepened when the Webbs left Santa Fe in September 1855. By the next month Kingsbury was concerned that Kate’s health and stamina were weary caring for their sick child. Kate’s health and state of mind were evidently so unsettling that Kingsbury wrote of his concern to her brother. Messervy responded with a rather stern rebuke directed at Kate:

She is the last person who ought to complain, and she should accept the condition of her little boy cheerfully and without a murmur. God placed him into your and her charge for a good and wise purpose, & it is her duty as a woman, as a mother & as a Christian to cheerfully—affectionately & pleasantly—without a murmur—to cherish & be proud of it—had it been my child, it would never have me an hour’s unhappiness. My rule is—‘What we can’t cure—we should cheerfully endure.’ Tell Kate, that as hard as she thinks her lot is—that there are but few who have been as highly blessed as herself.

The news from Santa Fe in the winter of 1856 that Kingsbury sent to Webb and Messervy was of a very slow market and increased Indian raids. At the end of April 1856, Kingsbury decided to send Kate and their son George to New England for the summer. They traveled with William Watts Hart Davis, the United States Attorney for the Territory of New Mexico and a trusted friend, as far as New York, where they were met by William Messervy. He would take them on to Salem, arriving there in June 15, 1856.

Kate must have been delighted to be reunited with her family, but that happiness would be short-lived. Her child George died on July 29 of an infection of the bowels. John had already begun his trip east to join them in Salem and Davis was traveling west back to Santa Fe; it was he who told Kingsbury the news of his child’s death. They were on the Santa Fe Trail at the Middle Crossing of the Arkansas River near Cimarron, Kansas. John hastened to Massachusetts, even neglecting to finish some of his buying and business negotiations in St. Louis. When he reached Kate in Salem, she was grieving and already quite relapsed into consumption. He wrote to Webb in October 1856 displaying his own grief and pledging his energy to return Kate to Santa Fe.

I found Kate as my letters had indicated very sick. She is on her feet & able to move about the house but that is all. Her cough is very troublesome and has got a strong hold on her. I have had a long consultation with her physician but could get no encouragement from him. He thinks her lungs are past cure. All that remains for me is to get her back again to Santa Fe if possible.

Waiting for the Doleful Last Crossing

Kate and John moved into the Messervy homestead in Salem for the winter of 1856–57. Her sister Eliza Ann was with them, as well as one of their New Mexican servants, Facunda. John wrote to Webb, who was in Santa Fe, suggesting that Lillie, who was in Connecticut, visit when she could, as that would cheer Kate—who was now often confined to her bed.

Kingsbury’s letters to Webb and Messervy vacillate between hope and despair. In November he wrote to Webb, saying he knew Kate could not live long with consumption and affirming that it was too soon to say if she would be able to withstand the trip to Santa Fe. Messervy wrote to Webb at the same time, doubting Kingsbury’s chances of returning Kate to their home in Santa Fe. As the year ended, Kingsbury wrote a long summation of her condition to Webb that showed his own inner struggle between hope and the fear that Kate would die:

Kate’s health I am sorry to say…is certainly no better. Her cough is still very troublesome, and in addition she is now confined to her bed with Rheumatism, this however, we hope is nothing permanent and may soon be relieved—but it is very unfortunate as it deprives her the privilege of taking fresh air, which is quite important in keeping up her appetite—In losing her appetite she will of course lose what little strength she had gained. I felt at times quite encouraged, but now do not know what to hope for. I fear every change, & look with dread for the next. It is now two weeks since she was out, she is in as good spirits as can be expected, the weather is pleasant & cold for this season of the year, the cold does not appear to affect her unpleasantly.

By January 1857, Kingsbury was determined to take Kate back to Santa Fe. He, perhaps on the advice of his doctors, believed it presented her only chance for recovery. The urgency of her health was wearing on John, who wrote Webb a long and quite emotional appraisal of the situation and his own anguish. He did not know what the best solution was for Kate, and he worried as well about the business:

Since my last letter the weather has been very changeable, extreme cold and then warm, which has been very trying for Katy. The last week she was again compelled to take to her bed, suffering severe pain in the chest and side—something like pleurisy. She is now just sitting up again. It has reduced her strength much. I have no encouragement from her Doctor or anyone else. She has already lived beyond their expectations. I am satisfied there is little hope for her here. I may be deseived [sic] but I cannot give up the hope that she may be able to start with me. The time is fast approaching and still it looks very dark. My mind is so harassed with anxiety for her that I am almost beside myself. I hope I shall have strength to do my duty. The disease is very flattering, and so far has been slow, and I think in spite of all opposition it will be a case of long & protracted termination. Her friends think different. They say if we start she will never reach St. Louis. If she remains there is but little hope of her getting through the summer. What am I to do? She is willing to start & wants to leave here, is very unwilling for me to leave her only for a single night. I feel very anxious to go out with the goods and relieve you and still intend too [sic], but it may prove otherwise, a week’s time may prostrate here so as to put it beyond a doubt and show me plainly what course to pursue. You may rest assured that I will not encroach upon your indulgence more than the necessities of the case will warrant.

By mid-March, John, Kate, and her sister Eliza Ann, as well as Facunda, were all on their way back to Santa Fe. Messervy was with them in New York, and even he had some hope that Kate would regain her health and make it back to Santa Fe.

They reached Westport Landing, Kansas, at the end of April, but were delayed there by the lack of grass and the difficulty and expense of finding mules for their wagons. Kingsbury estimated that 800 wagons would reach Santa Fe as soon as the grass was available. Kingsbury had little choice but to use oxen to pull his wagons. While this might make the animals less attractive to Indian raids, he was concerned that the slow pace might delay getting Kate to Santa Fe where there was the fresh air and rest she needed.

In separate correspondence, Messervy and Webb shared their concerns that Kate would make it to Santa Fe. Messervy asked Webb to see that his other sister Eliza Ann would be well taken care of and safely returned to Salem should Kate die on the trail.

As they approached the Lower Crossing of the Arkansas River east of Dodge City, Kansas, Kate’s health took a turn. Her breath was labored and she slipped into delirium, marking the last and fatal stage of consumption.

Kate died there on June 5, 1857. John Kingsbury had prepared for just such an emergency. He had packed a metal coffin in one of the wagons. John, Eliza Ann, and their close friends Mr. and Mrs. Tom Bowler accompanied Kate’s body to Santa Fe, covering the 375 miles in a record eleven days. Webb later described her last night:

Mrs. Kingsbury was at no time improved in health on the whole route….She urged her husband and sister to take all care and persevere in trying to save her and then just after midnight she seemed to realize the end was close. She said, ‘is it possible that I have come this far on my way and must now take leave of you all?’ She then commended with perfect composure, and took leave of her sister and John. She wished to assure them that the course they had pursued was in every respect to her satisfaction, and asked forgiveness for every hasty expression, or unkind word that had passed her lips during her illness, her every wish had been complied with, and everything in the power of man had been done to promote her comfort.

‘And now,’ said she, ‘if my Heavenly Father has sent for me, I am ready to go. I leave myself in His hands, having the fullest confidence in His justice and mercy. Don’t regret, or grieve over the step you have taken. I have taken leave of everything behind; I have got everything with me. Oh,’ said she, ‘I am very tired and now let me go to sleep.’

Eliza Ann says that the whole scene of that night was the most overwhelmingly sublime that she has ever witnessed or imagined, transcending the power of man to describe. Not a cloud in the sky—not a breath of air swept over the plain—

not a sound of man, beast or fowl to break the stillness of the night—all nature seemed hushed and subdued to silence by the sublimity of the scene. The moon shone in her most dazzling splendor, and the majesty and power of God seemed to pervade all nature. At 6 o’clock, all was over.…

She died in the peaceful knowledge that her husband had made all the proper arrangements for her body, and indeed he had. He pulled from one of the trains a crate labeled “private stores” and in it was a metallic coffin. Mrs. Bowler and Facunda laid out the body and by 9 o’clock they had completed their duties.

Despite their best efforts, Kate Kingsbury did not make it across the Santa Fe Trail that third time, but she was rewarded with a beautiful death under a moonlit night attended to with the careful ministrations of her family and friends. She was laid to rest at the end of the Santa Fe Trail, beneath a headstone honoring her memory that John ordered carved and later transported to Santa Fe.

—

To learn more about Kate’s resting place and the stories of Santa Fe’s cemeteries explore Kate’s Final Journey.

Frances Levine is president of the Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis, and the former director of the New Mexico History Museum and the Palace of the Governors.