Pasó por Aquí

Generations of explorers and artists traverse the path of an historic expedition

Gregory Mac Gregor, Green River crossing site, Dinosaur National Monument, Utah, 2008. Courtesy the artist.

Gregory Mac Gregor, Green River crossing site, Dinosaur National Monument, Utah, 2008. Courtesy the artist.

By Dr. Alicia M. Romero

“For through the lack of expert help we made many detours, wasted time from so many days spent in a very small area, and suffered hunger and thirst. … But God doubtless disposed that we obtained no guide, either as merciful chastisement for our faults or so that we could acquire some knowledge of the peoples living hereabouts,” wrote Fray Francisco Atanasio Domínguez on November 7, 1776, just as he, Fray Silvestre Vélez de Escalante, and their exploration party successfully traversed what is now known as the Crossing of the Fathers at Lake Powell, between Utah and Arizona. They were making their way back to Santa Fe after an unsuccessful attempt at finding an overland route to Monterey, Alta California, to connect colonial Mexico’s far northern lands. Escalante’s journal documented details in the land that would have been used to determine settlement and agricultural potential, as well as possible exploitation of natural resources. Additionally, because two priests led this survey expedition without any actively serving soldiers accompanying them, their interests in proselytization potential of Native people from New Mexico to California was likely just as important as forging the overland route itself.

Domínguez and Escalante’s expedition in 1776 inspired multiple generations of people to recreate their journey. In the early 2000s, photographers Siegfried Halus and Gregory Mac Gregor set out with their cameras and maps in hand to document the contemporary changes to the land that Domínguez and Escalante traversed nearly 235 years prior. Halus and Mac Gregor’s photographs are the basis for the New Mexico History Museum’s long-awaited exhibition, In Search of Domínguez & Escalante, on view through fall 2022 in the Palace of the Governors and based on a book of the same title.

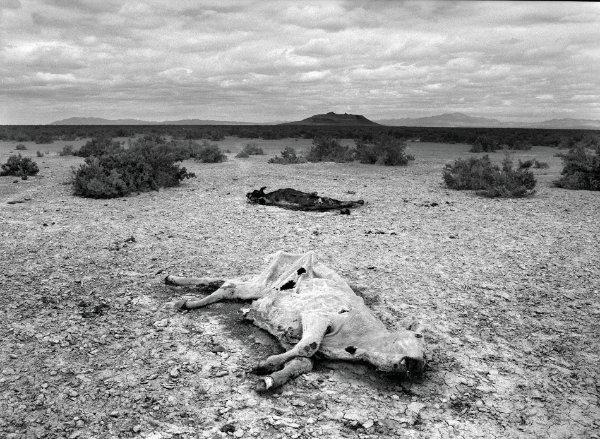

The juxtaposition of Escalante’s journal entries, available in the original Spanish and in a contemporary English translation, with forty contemporary photographs from Halus and Mac Gregor, invite the viewer to consider the vast changes throughout the terrain since the 1776 exploring party stumbled across what is now the Four Corners area so many years ago. Halus and Mac Gregor sought to portray the land laid before them with visual precision similar to that of Escalante’s written descriptions, all the while putting into perspective the rapid environmental change of some of these areas due to human activity and industry. In order to accomplish this monumental task, Halus and Mac Gregor studied both whom and what the friars met along their way.

Domínguez and Escalante, plus an initial group of eight, planned to leave Santa Fe for Monterey on July 4, 1776, but were delayed twenty-five days before finally setting out on what became a five-month expedition. (Of course, they had no idea what other major event was happening on that significant day, thousands of miles to the east.) Despite covering over 1,800 miles of terrain, the group never made it to Alta California; they ended up back in Santa Fe on January 2, 1777, likely feeling defeated at being unable to complete their task at hand. That the exploration party knew little of what to expect as they attempted to reach Alta California is no surprise, given the vast terrain they intended to cross during one of the most difficult seasons of the year.

Fray Francisco Atanasio Domínguez, at 36 years old, originally from Mexico City, led the expedition. Fray Silvestre Vélez de Escalante, 26 years old and born in Spain, was formerly priest at Our Lady of Guadalupe at Zuni Pueblo and chronicled the entire journey in writing. His extensive daily entries included descriptions of people, weather, flora and fauna, rivers, mountains, canyons, and distance traveled. Of course, he also included blunt descriptions of frustrations and illnesses, especially when it came to the “stomach trouble” of the party’s cartographer, Bernardo de Miera y Pacheco, who fell ill more than once on the journey.

Because Escalante chronicled the expedition, generations of scholars erroneously attributed him with commanding the party and nearly omitted Domínguez completely. In fact, it was actually Domínguez who brought Escalante on and convinced Governor Pedro Fermín de Mendinueta to fund their journey. This long-lasting error was perpetuated throughout the Four Corners area, specifically southeastern Utah, as one can attest to the number of places named solely for Escalante.

Another key member to the party was de Miera y Pacheco, highly recognized cartographer, artist, army engineer, and soldier—among other notable professions. Miera y Pacheco meticulously plotted the geographic features and put down on paper what Spanish-language names Domínguez and Escalante gave these “newly discovered” lands and people. His were among the first maps created of the area, and he remained an influential member of Santa Fe society throughout his life.

A number of other men accompanied the expedition, though few, if any, have received recognition for their role in the effort. Andrés Muñiz, a Nuevomexicano guide from Bernalillo and Ute interpreter, was among the vecinos—Spanish-speaking citizens of the territory—who traveled with Domínguez and Escalante. Also important were the number of Genízaros, Pueblo, and Ute people who either began or joined the expedition as the group made their way through Ute lands. Some of these Indigenous individuals were described in contemporaneous writing as joining “voluntarily” or by coincidence; some were also “given” from the tribes. We can’t be sure how much of their participation was voluntary or not. People such as Juan de Aguilar (Santa Clara Pueblo), Simón Lucero (Zuni Pueblo), Juan Domingo (Abiquiú Genízaro), Francisco (Ute), and Atanasio (Ute) made this journey possible, although their roles were diminished in favor of the friars’ description of and interactions with Indigenous people, the atmosphere, and their own hardships.

They first traveled northward through the Pueblo de Santa Clara and the Pueblo de Santa Rosa de Abiquiú before finding the Sierra de la Plata and the Río de Nuestra Señora de Dolores, or the Dolores River, in southwestern Colorado. As they moved farther on, the party soon met Motawei, Taviwatsiu, Mowataviwatsiu, and Ute communities in southeastern Utah. Escalante described these and other Indigenous people either favorably or badly depending on whether or not they were welcoming of the Nuevomexicanos. On the one hand, Domínguez and Escalante met Native people who, the friars felt, were accepting of their missionizing efforts; these groups were spoken of with sensitivity and high regard as “gentle and affectionate.” On the other hand, other Indigenous people maintained clear boundaries with Domínguez and Escalante. In one remarkable instance toward the end of the journey, the party met with Hopi people who welcomed and provided provisions for the Nuevomexicanos—but outright rejected their Christianity. In turn, Escalante remarked that the party “withdrew quite crestfallen back to [their] lodgings after seeing how invincible was the obstinacy of [those] unfortunate Indians.” Many of the journal entries featured alongside Halus and Mac Gregor’s photographs include these complex interactions, as the photographers keenly recognized this clash of cultures that often resulted in spiritual misunderstandings and uneven power dynamics, much like today.

© Siegfried Halus, courtesy Maximilian Halus.

After the group realized that winter was on the horizon and they seemed to be far from their destination, a decisive vote was cast to return to Santa Fe rather than continue to Monterey. Had they continued northwest, they would have likely encountered the Great Salt Lake next, but they headed south instead. Upon changing course, the party redirected their path through northeastern Arizona, where they met Havasupai and Hopi people. Amazingly, they both circled and crossed the Grand Canyon.

The story of Domínguez and Escalante has inspired generations of people to embark on the same journey and attempt to experience what the friars saw long ago. Still, others followed the journal to find a possible inscription marking their passage through the land, which is a typical human activity not limited to colonists. Siegfried Halus and Greg Mac Gregor’s 2011 ambitious photographic project to document the 1,800-mile trail is the most contemporary of these efforts, though theirs differed in intention and result.

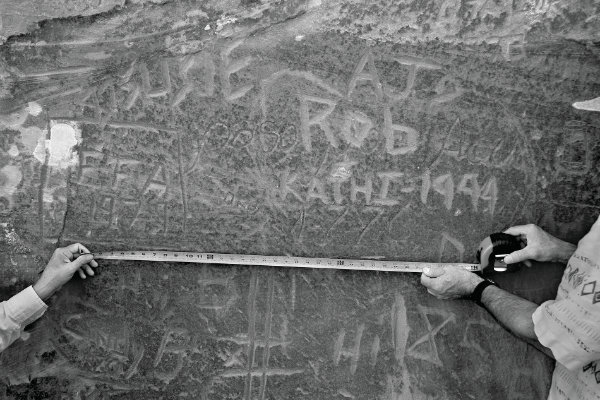

The first recorded retracing of the route came from Harry L. Baldwin who, as he prepared maps for the United States Geological Survey in 1884, came across what he believed was Escalante’s 1776 “pasó por aquí” rock inscription in northern Arizona. Years later, in October 1939, Dr. Herbert Bolton of the University of California, Berkeley, Dr. George Hammond of the University of New Mexico, Jesse Nusbaum of the National Park Service (at that time), and two unnamed Diné guides, among other academics and archaeologists, set out to verify Baldwin’s claims.

That endeavor proved fruitless—Baldwin was unable to accompany Bolton’s group, and they never found Escalante’s inscription. In typical fashion, Jesse Nusbaum took his camera and photographed the party on horseback and on foot as they journeyed along an area of the Colorado River in Glen Canyon, Utah, near the Crossing of the Fathers (named for Domínguez and Escalante).

Despite not finding Escalante’s rumored inscription in 1939, Bolton eventually trekked much of the Domínguez and Escalante trail and produced Pageant in the Wilderness, a 1951 publication that offered a map, translation of Escalante’s journal, and astute, firsthand observations from Bolton the explorer himself.

Then, in 1976, Fray Angélico Chávez produced a new translation as part of the Domínguez-Escalante State/Federal Bicentennial Committee; scholars from the University of Utah followed this updated translation and corrected a number of cartographic inaccuracies for an updated USGS map of the route. Participants from New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado, and Utah embarked on a reenactment of the trail as part of the bicentennial celebration.

Nearly twenty years later, Dr. George C. Baldwin, son of Harry Baldwin, finally located the inscription in the Echo Cliffs area of northern Arizona with the help of volunteers and support from the Palace of the Governors. Surprisingly, in 2006, two volunteers from the National Park Service at Lake Powell found another inscription attributed to the friars: “Pasó por aquí, anyo 1776.”

So although Halus and Mac Gregor weren’t the first to follow Domínguez and Escalante’s journey, their project differed substantially from others. Using technology like GPS, unavailable to earlier groups, Halus and Mac Gregor located with as much accuracy as possible each and every stop for which Escalante wrote a journal entry. And they photographed what they saw. Sometimes the landscape appeared relatively unchanged, save for a fence or two. In other locations, however, it was clear from Escalante’s descriptions and the passage of time that many areas had experienced radical transformations due to increased human activity and settlement of the area. Many of their photos document remnants of large-scale ranching, industrialization and infrastructure in power plants and dams, and trash-strewn stretches of land. Clearly, as Halus and Mac Gregor demonstrate, much of the area that the 1776 group explored would be unrecognizable to them, and perhaps even to Bolton’s 1939 party.

In Search of Domínguez & Escalante promises to inspire the viewer, encourage appreciation for inquiry and determination, and put into perspective the limits and impact of humankind at any given moment. As Siegfried Halus observed of the 1776 journey and his and Mac Gregor’s documentary project: “We became bound by mutual amazement over the difficulties we encountered as modern pilgrims on the heels of Domínguez and Escalante. We looked east, west, north, and south as we tried to formulate a coherent vision of what these friars must have imagined so long ago. … Nevertheless, we photographed all the identified sites, making it a point not to reject what we saw, and ultimately coming to terms with the vicissitudes of time.”

Unfortunately, Halus passed away in 2018 just as this exhibition was being planned for the Palace of the Governors. We hope that students of photography, New Mexico history enthusiasts, caretakers of the environment, and adventure-seekers might better imagine what Domínguez, Escalante, and their compañeros experienced through Siegfried Halus and Greg Mac Gregor’s contemporary photographs of a centuries-old journey.

—

Dr. Alicia M. Romero is curator of Nuevomexicano/a history at the New Mexico History Museum. She graduated with a BA and MA in history from the University of New Mexico and a PhD in history from the University of California, Santa Cruz.