Excavating the Past and Present

Understanding Black-Mexican identities

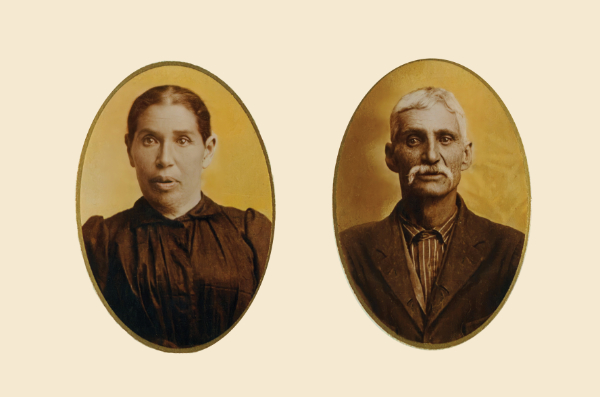

Francisco and Justa Catalina Martinez—parents of Adelaida Barela—married at the oldest church in Colorado in 1865 and were awarded a 160-acre land grant in 1901, reflecting the settler colonial history in the author’s family. Photograph circa 1880–1900, courtesy Robert Quintana Hopkins.

Francisco and Justa Catalina Martinez—parents of Adelaida Barela—married at the oldest church in Colorado in 1865 and were awarded a 160-acre land grant in 1901, reflecting the settler colonial history in the author’s family. Photograph circa 1880–1900, courtesy Robert Quintana Hopkins.

By Robert Quintana Hopkins

One email can radically change your understanding of yourself. I received that email in 2015 from Hannah Abelbeck, photo archivist at the New Mexico History Museum. A 1915 photo of Sam Adams at the Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (see “Sam and the Adams Family“) prompted a multi-year exploration into his life story by Hannah and me. I am a descendent of Timotea Chavez, Sam Adams’ wife. Over six years, Hannah and I have shared notes and records and engaged in conversations to better understand Sam and Timotea’s experiences. What follows is my firsthand account of how learning Sam and Timotea’s story changed my understanding of myself.

I was born in 1970s California to a Mexican American mother, Bonnie, and an African American father, Robert Charles. My sister Shane and I grew up navigating our bi-racial and bi-cultural identities, believing we were the first Blacks in our Mexican American family.

Our Blackness was significant among our relatives. My parents, responding to their families’ disapproval of their relationship, eloped, leaving their respective families in the Central Valley of California and moving 350 miles south to Los Angeles. They started their own family with my birth, and as a result, my mom’s father, a grandfather I never met, disowned her, never reconciling their relationship before his death. My mom remembered her family’s race prejudice and consciously decided to protect my sister and me from it by raising us in California with my dad’s immediate family and her own younger sister, not in Colorado with her extended family. In our youth, our Mexican American identities were shaped almost exclusively by our mom and her sister, Georgina.

Our environment was filled with symbols of our Mexican heritage—symbols that, like most elements of culture, were so normal they were not recognized as significant. On weekends our mom often served chorizo and eggs with fried potatoes for breakfast, or large pancakes she made on a cast iron comal. As teenagers our primary snack was a plastic tub of homemade salsa fresca and a bag of store-bought chips. She taught us to make chile verde, two versions of Mexican rice, menudo, guacamole, and beans. From the black wrought-iron chairs and table in our kitchen, red clay Mexican pottery with multi-colored papier-mâché flowers next to the fireplace, or the wooden kitchen utensils hanging near the stove, including a rolling pin, spatula, spoon, bean masher, and molinillo for mixing hot chocolate, there were small, subtle reminders of our Mexican roots.

As a graduate student in anthropology during the late 1990s, I decided to write an autoethnography as my master’s thesis. Writing my own story and researching my family’s history was my way to resist the colonial roots of the field, in which whites researched people of color, controlling and commodifying knowledge and narratives. I wanted to show that we could tell our own stories in our own voices, turning the researcher’s gaze internally, so that the subject and researcher became one, and the power to represent another shifted to the power to represent one’s self.

I began interviewing the people around me: my parents, my paternal grandmother, Bennie Mae, and her mother, my great grandmother, Jessie Ann. I regularly interviewed my paternal grandfather Robert’s eldest sister, Llemma Mae. I spoke with my dad’s sister, Carolyn, and my mom’s sister, Gina. I visited extended family on both sides, researching my African American family in Utah, Texas, and Arkansas, and my Mexican American family in Colorado, and performed archival research in New Mexico. I was embraced by the elders on both sides of the family. I met my maternal great-grandmother Sidelia’s brother, Manuel, who lived to be 98. I interviewed my maternal grandmother Irene’s sisters, Geri and Dolores, and her cousins, Viola and Lucy, and my maternal grandfather’s cousin, Ercie. Through my cousin Nikki I learned of my great-great-grandmother Timotea, our Great-Grandma Tillie’s mother. Generously, my family shared the stories of our ancestors, making them my stories too, as if one generation bestowed our family narratives to the next, ensuring my ancestors would continue to live in our collective memory for generations to come.

As we sat at her kitchen table eating homemade tamales and menudo, Aunt Viola told me about my maternal great-great-grandmother Adelaida Barela. Adelaida’s parents left New Mexico and settled in Southern Colorado, one of the first Mexican families to settle in the region. Her parents, Francisco and Justa Catalina Martinez, were born in New Mexico when it was part of Mexico. Their parents were born in New Mexico when it was a Spanish colony. Francisco and Justa Catalina married at the oldest church in Colorado in 1865, eleven years before Colorado became a state, and were awarded a 160-acre land grant in 1901, reflecting the settler colonial history in my family.

The family moved north via horse and wagon, living in Walsenburg and Pueblo, finally settling in the Fort Collins area around 1906, working as farm workers in the sugar beet, barley, and wheat fields of Larimer County. Adelaida was widowed after her husband, Francisco Barela, died from injuries sustained in an automobile accident in 1921. According to oral history, Francisco was half Navajo and half French, a reflection of the long history of mestizaje also present in my family. Aunt Viola described Adelaida as a loving grandmother who helped raise many of her grandchildren and faithfully attended mass at Holy Family Catholic Church every morning.

Born in 1915, cousin Lucy recounted her memories of my great-grandparents Roy and Sidelia Vigil, her aunt and uncle. They were married in 1928 in Fort Collins. Roy was 21 and Sidelia was 28. They moved to Denver to raise their six children. Cousin Lucy lived with them for a while. Roy worked as a chef at the Cosmopolitan and Brown Palace hotels, while Sidelia was a homemaker, cooking and sewing for the family and spending summers in Fort Collins canning vegetables and fruits with her sisters Mary and Opal. Lucy described the segregation Mexicans experienced in theaters, restaurants, and other businesses, with signs that said “White Trade Only.”

First, the family lived in a poor, but racially diverse neighborhood in East Denver and later moved to a mostly Italian neighborhood in North Denver. Proud of the family’s Spanish roots, Lucy applied a critical lens, describing how our ancestors became second-class citizens in “their own country,” working for German and Russian “foreigners with money” as a result of being poor. Silently, I applied the same critique to our family, aware that our presence negatively impacted Indigenous communities.

My mom told me about her grandmother Tillie, originally born in New Mexico. Tillie raised my mom and her sister Gina. Widowed after the death of her husband, Raymond Quintana, who was sixteen years her senior, my mom described Tillie as strict and independent. She worked as a day worker for the wives of two local doctors and wanted upward mobility for her granddaughters. Education and assimilation were the paths she encouraged them to take for a better life.

Through archival research I found census records of Timotea, Tillie’s mother, in Galisteo, New Mexico. One record in particular caught my attention. The 1900 Census lists Timotea and three children. While Timotea is listed as white, the three children are listed as Black. Not being sure if this was the right family, I saved the record, but questioned its pertinence to my search. Several times my mom had told me that she suspected someone in the family was part Black. She thought it may have been one of her uncles. I always brushed off her assertion as speculation.

Eventually, I was contacted by Grandma Tillie’s niece, Cecilia. Cecilia was Tillie’s eldest brother Nestor’s daughter. Cecilia confirmed that the record was indeed our family. She told me that Timotea had married Sam Adams, an African American man, and that some of the sisters were mixed-raced. She told me that her parents lived with Timotea in Galisteo when they first married in 1914 and that she had stayed in contact with her cousins, Irene and Jane, for years via phone calls and Christmas cards, before losing contact.

I wondered about the experiences of Timotea and Sam’s mixed-raced daughter, who I discovered was named Paublita. My sister and I were raised within the context of an Anglo ideology that governed the social and legal classification of race, with whiteness defined as the absence of Blackness. The “one-drop rule” established that anyone with one drop of Black blood was Black. I questioned whether or not Paublita, too, was monoracialized, in spite of navigating the world with a multi-racial identity and sense of self, like us.

In 1970’s California there was no language to identify children who were both Black and Mexican. Forms and census records forced you to choose. This wasn’t true in Colonial New Spain. Colonial New Spain had a multitude of names to describe racial identities, such as mestizo, mulatto, pardo, and zambo, among others. Race was more fluid. Native American scholar Jack D. Forbes used census records to show that residents of Mexican California changed racial categories over time, and educator and scholar Edgar Love used colonial church records to show interracial marriage patterns in Mexico City.

I wondered if Paublita, who was born in New Mexico only forty-one years after the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, experienced a more fluid racial context, like that of the Spanish Colonial period, or a binary racial context as a result of the Anglo influence after 1848. I wondered if Paublita maintained a Black identity, held a Mexican identity, or created a new mixed-raced identity like me. I self-identify as AfroChicano. Did she “pass” as Mexican? Do her descendants know they have African ancestry? Was she proud to be both?

For a long time I bemoaned the fact that my generation didn’t know about Paublita and that no one in our family today is in contact with her descendants. Was their erasure from our collective memory and oral history intentional? I speculated that the family’s silence was due to her mixed-raced background. I was relieved when I discovered that Paublita died in 1945, before my mom was born. My relief was due to the fact that I know that around 1964, Grandma Tillie and her brother, Nestor, travelled from Colorado and California, respectively, to visit Paublita’s husband, Isidro, and children, Jane and Irene, in New Mexico; this tells me that nearly twenty years after their sister’s death, they were still visiting their brother-in-law and nieces. Race, for that generation at least, did not divide the family.

All our lives, my sister Shane and I grew up thinking we were the first Blacks in our Mexican American family. Sam Adams and Timotea’s marriage reveals that our story is not as unique as we thought it was. There must be many untold stories of people who have loved and married across racial categories and across identities, creating new notions of family and identity, preserving, mixing, and recreating cultures, passing on the old, while creating something new in a constant state of emerging, unfolding, and “becoming” within a context that at times supports and at times challenges what and who is created. So much is unknown about Sam, Timotea, and Paublita, but their stories remind us that there have always been brave people who have challenged norms and crossed geographic and racial borders, living at the intersection of multiple cultures and identities. Through Sam, Timotea, and their descendants, we see New Mexico as a site in which multiple people, histories, cultures, and genes converge in a complex web of human experiences still waiting to be fully understood.

—

Robert Quintana Hopkins is an AfroChicano descendant of the Martinez, Barela, Quintana, Chavez, and Vigil families from Colorado and New Mexico. He was born and raised in California and currently resides in the San Francisco East Bay, where he works as an organizational development practitioner and is completing a PhD in organizational psychology. In his spare time he writes poetry and facilitates a monthly writing group.