Challenging History

The Conception and Crafting of A World-Class Exhibition That Honors One of New Mexico's Darkest Chapters

The Bosque Redondo Memorial as viewed from above, looking north by northwest. Photograph by Tira Howard.

The Bosque Redondo Memorial as viewed from above, looking north by northwest. Photograph by Tira Howard.

By Charlotte Jusinski

The town of Fort Sumner, New Mexico, is quiet and pastoral. The streets of the farming and ranching community are gravelly and pocked, and rusty signs for Billy the Kid’s grave or Fort Sumner Lake dot the shoulders like tired but richly patinaed sentinels. Sometimes the whole town smells vaguely of petrichor, thanks to the Pecos River lurching lazily through the plains nearby, and irrigation ditches lining the streets fill the fields thick with green crops each spring and summer. Horses whisk their tails near pickup trucks and tidy barns. The floodlights outside the Dollar General buzz. A car stops at the Dariland drive-thru for a cheeseburger and a milkshake.

About three miles from the town center, down Billy the Kid Road to the southeast and just past the gravesite of the famous outlaw, is the eponymous fort, established in the nineteenth century. None of the buildings from that time remain, but a herd of churro sheep graze quietly in a field adjacent to the old military parade grounds.

Rather than musty old adobes, the location is dominated by a relatively new building: the Bosque Redondo Memorial, a state historic site. The building, which presents as a modern take on a teepee melded with a Navajo hogan, is impressive but not large. With only 6,500 square feet of exhibition space, the site endeavors to fairly and accurately recount a history that seems widely unknown: that of an American concentration camp.

It’s a story that is vital to the understanding of the American government’s relationship with Native Americans, not only when the camp was in operation in the 1860s, but right up to today. It’s a story that has been years in the making, if not decades, or perhaps centuries; it’s taken a long time to get it right, or as close to right as possible. It’s a story as emotionally charged as any about genocide, forced removal, survival, racism, and resilience.

It’s a story that the state of New Mexico has been trying to tell for a long time—an endeavor which has finally come to pass in a sweeping new exhibition led by Indigenous communities and pieced together by deeply invested parties.

It’s a story that one could say started in 1492, or 1864, or 1990, or 2017. But most importantly, it’s a story that will forever evolve.

This is only one version.

The Letter

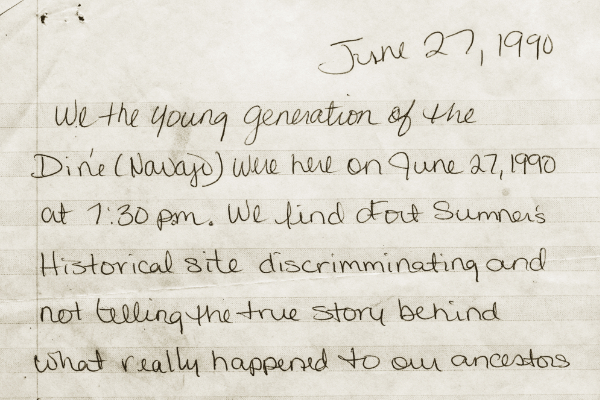

One summer morning thirty-two years ago, a ranger at the Bosque Redondo Memorial was walking the grounds when they came upon a folded letter carefully tucked in a rock shrine. The ranger brought the mysterious letter inside to show to their colleagues; it seemed to have been left by a group of students who had visited the site the day before.

“We the young generation of the Diné (Navajo) were here on June 27, 1990 at 7:30 pm,” the letter begins. “We find Fort Sumner’s Historical site discriminating and not telling the true story behind what really happened to our ancestors in 1864-1868.”

The letter, signed on the back by twenty students, continues: “It seems to us there is more information on ‘Billy the Kid’ which has no significance to the years 1864-1868. We therefore declare that the museum show and tell the true history of the Navajos and the United States Military. We are a [concerned] young generation of the Navajos for the future.”

Indeed, the exhibition at what was then Fort Sumner State Monument wasn’t a memorial, nor was it about the Bosque Redondo. The exhibition focused mostly on the army fort operations at the site, touched briefly upon the incarceration of Indigenous people there, and made significant mention of Billy the Kid. The outlaw died behind a house, since razed, back behind the parade grounds; a phonebook-sized plaque marks the site.

Even more egregiously, every single iteration of the exhibition at the site since its founding in the 1970s had been prepared by mostly white state employees with no input sought from Indigenous communities.

But with the letter from the Navajo students, the trajectory of the historic site was about to change. It would take a few decades, a few directors, and more than a few iterations. Eventually it led to a collaboration that spanned from the Navajo Nation to Oregon to Santa Fe to New Jersey to the Mescalero Apache Reservation.

On May 28, 2022, with the grand opening of a new exhibition, Bosque Redondo: A Place of Suffering…A Place of Survival, the story of the site will enter its next chapter.

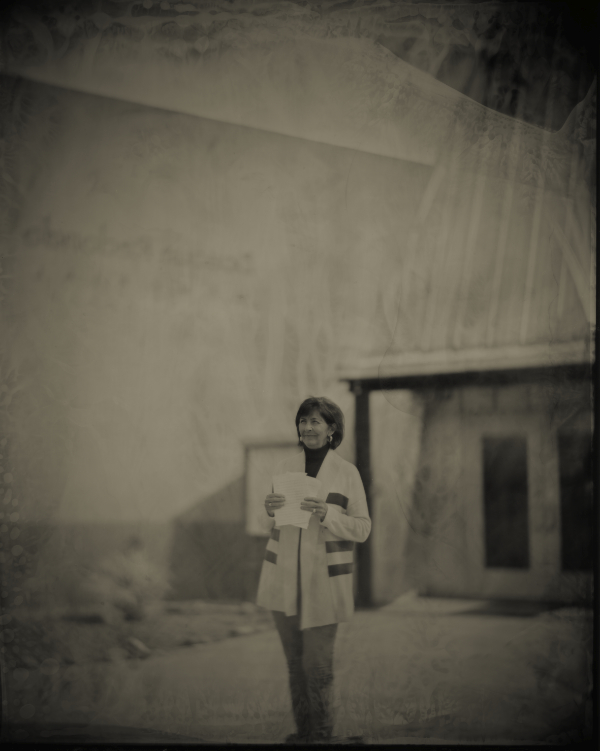

Photograph by Tira Howard.

Hwéeldi

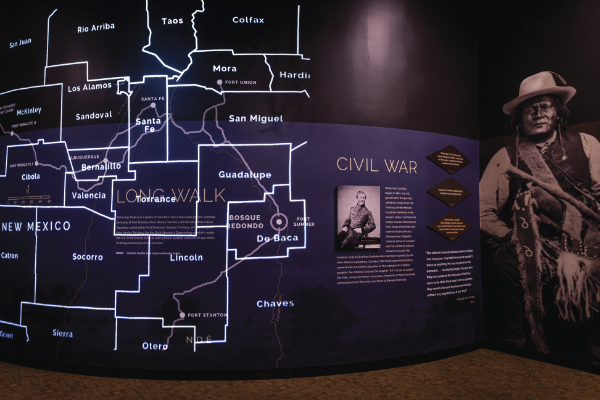

The 1800s were a tumultuous time in the American West, as white colonizers blazed new paths across lands already colonized by Spanish conquistadors and the Mexican government. In New Mexico, Navajos (Diné) and Apaches (Ndé) had come to be known by settlers as particularly “problematic” people often blamed for raids and thievery. The solution, according to the United States government, was mass incarceration and cultural genocide.

Chasing down the nomadic Mescalero Apaches through Southern New Mexico resulted in a small number of that band surrendering to the government. Then, through a brutal campaign of scorched earth and a vicious war of attrition, Kit Carson led a band of soldiers to Dinétah and into the heart of Canyon de Chelly to force the Navajo people to turn themselves in. Carson, relaying the promises of the government, assured the Navajos that if they surrendered, they would be well cared for as charges of the United States.

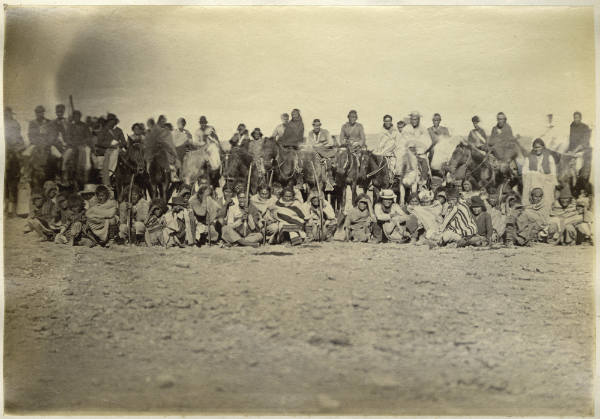

What in fact happened was a forced march of hundreds of miles from the Four Corners region to eastern New Mexico, to a newly established frontier outpost called Fort Sumner. Thousands of Navajos started what they called the Long Walk from their homelands to Fort Sumner. Hundreds died en route, and more were kidnapped and forced into slavery along the way. Mothers were forced to give up their children in villages they passed through, while soldiers shot and killed sick or weak people who fell behind. It was weeks before the line of thousands reached their destination in the dead of winter in 1864.

The area around the fort, a 40-mile square the Spanish had dubbed Bosque Redondo, was a site chosen by U.S. General James Carleton. Supposedly an idyllic landscape for Indigenous people to learn the virtuous sedentary life of farming on the banks of the Pecos River, it was offered to the Diné and Ndé people as their new home, a place where they could live in peace—as long as they didn’t leave or cause any further trouble to colonizers.

After the horror of being forced off their homelands and enduring the Long Walk, at first there seemed to be a few dim glimmers of hope at the site. The Bosque Redondo was actually already known to the Mescalero people as a peaceful, shady site perfect for pit stops for small groups in summer. The Navajos, meanwhile, took pride in their farming prowess, and for a time there was plenty of firewood, the corn at the Bosque grew tall, and it seemed there would be plenty to go around.

The hope didn’t last. The water of the Pecos was alkaline and unfit to drink. It wasn’t long before a worm infestation, then bad-luck weather, destroyed the crops. Even on a million acres, there wasn’t enough firewood to feed the campfires of thousands of people. There weren’t materials to build proper hogans, so the people were forced to dig into the earth and lay branches over the ground for shelter. The barren landscape couldn’t feed even a fraction of the population of Bosque Redondo.

On November 3, 1865, the Mescalero Apaches had had enough. They were greatly outnumbered by Navajos at the Bosque, and tensions between the tribes were high, in addition to the abysmal conditions at the fort. The Apaches appointed nine people who were either too old or too ill to travel to tend to fires throughout the night to fool the guards into thinking the Mescaleros remained at their camps; and then, under the cover of darkness, 400 Apache captives snuck away in the night, spreading in all directions to evade pursuit.

Conditions did not improve for the people left at Fort Sumner. Servicemen sexually assaulted young girls, leaving them “payments” of ration tickets or cornmeal; children dug corn kernels out of mule manure to eat; people walked miles every day to wrest scant mesquite roots out of the ground to feed meager fires. Disease and malnutrition were rampant. One out of every three captive Navajos—three thousand in total—died at the concentration camp.

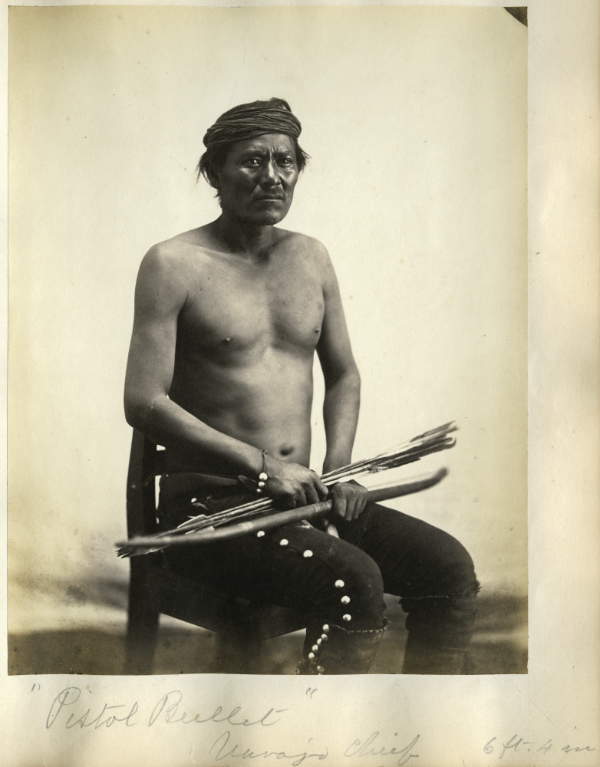

In May 1868, the government finally admitted what had been clear since the beginning, and agreed to shut down the Bosque Redondo. Navajo chief Manuelito, medicine man Barboncito, and other headmen of the tribe signed the Treaty of 1868, which allowed the Navajos to return to their ancestral lands and established the boundaries of the Navajo Nation. On June 18, 1868, the remaining captive people began the 400-mile walk back to Dinétah.

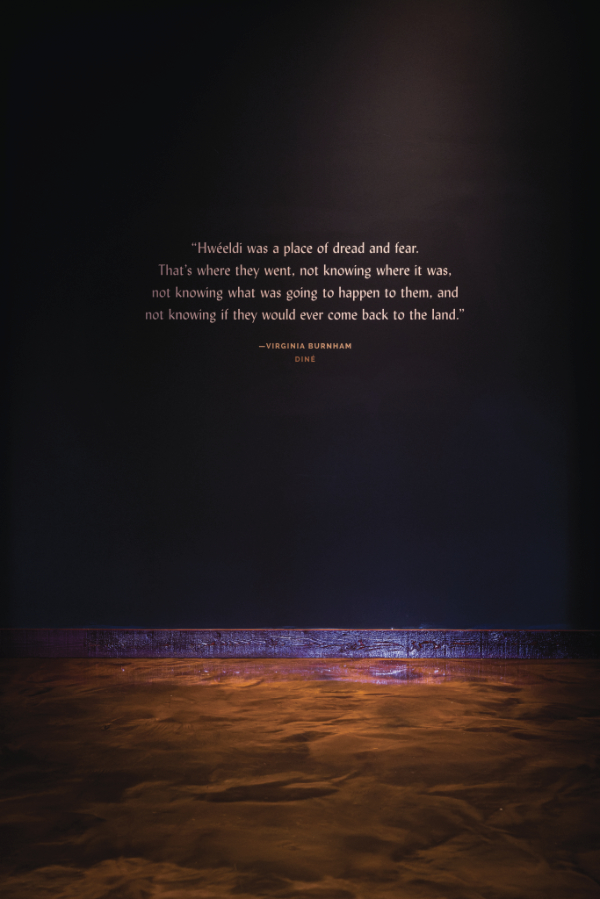

The incarceration experiment at Bosque Redondo had been a resounding failure. The place would forever be known to the Navajos as Hwéeldi—a place of suffering and fear.

The People

Only one individual has been consistently involved with the Bosque Redondo Memorial through all of its recent iterations, and most will cite a single name as its matriarch: Mary Ann Cortese.

Cortese, a retired school teacher, is the president of the Friends of the Bosque Redondo Memorial, a nonprofit sister organization. She has been a tireless advocate of telling the entire truth of the site since 1995, and her work with the memorial has become more than a project. It’s integrated with her very life.

When asked how she’s stayed so passionate, she remains modest. “You know, I believe in the project,” she says with poise, seated elegantly in an office at the historic site. She often says, “When I stop crying when I tell this story, I need to quit. When I lose the passion for it, I need to step out. So far, I haven’t lost that.”

The Friends of the Bosque was always involved in the exhibition planning as an auxiliary group, and Cortese says problems emerged early on with some of the early designs. “The first one was dioramas, mannequins. Very oldschool exhibits.” Worse, she says, “Neither one of the tribes were contacted. Neither one was involved.”

She continues, “Being an educator and being a counselor, you have to get down to the nitty-gritty of a problem in order to solve it. You’ve got to be able to solve it in a way that it doesn’t come back, hopefully.”

The nitty-gritty of this problem, of course, was the exclusion of the Navajos and the Mescalero Apaches from the process. It was nearly the 150th anniversary of the Treaty of 1868 before Indigenous groups were involved and consulted from the very earliest stages of exhibition planning.

And then, through a mix of timing, personal passion, and ambition, Director Aaron Roth took up the mantle at the site. Roth moved to Fort Sumner in 2014 and took a job as a ranger at the Bosque Redondo Memorial, but it wasn’t long before he was promoted to site director at a pivotal time in its evolution.

Many facets of Roth’s education as an historic archaeologist, not to mention his ancestry, especially equip him to aid in leading at the site. Prior to World War I, sensing oncoming trouble for Jewish people, his father’s side of the family left Germany and changed their name from Rothstein.

Of the maternal side of his family, Roth says: “His father told him to get out of Germany just before the onset of [World War II],” referring to his grandfather and great-grandfather, who were half-Jewish and Jewish, respectively. His grandfather eventually enlisted in Canada, and was shot down over the English Channel.

“He came back to the United States because he said, ‘I cannot return to Germany, my home, because it is a graveyard to me.’” Roth pauses. “I think about that.”

He continues, “I know that we don’t explicitly state that this place has its connections to other concentration camps around the world, but it does. … It’s my driving force.”

Upon his arrival, Roth was presented with a “finished” exhibition plan that still felt incomplete; as he says, all that was left was to choose the paint color for the rotunda. But it still wasn’t right. He took the drastic step of scrapping everything. “The history that we told over the years is not incorrect. It’s just not complete,” he says. “The fact that we have shied away from that is what’s upsetting to me. It’s something that happened. To deny it, that’s the injustice.”

So Roth and Jeff Pappas, then the director of New Mexico’s historic sites, went back to the drawing board. And the time is right, Roth says, to talk about difficult histories. “You can’t do something anymore without being seen,” he says, referencing ubiquitous social media and a twenty-four-hour news cycle. “I think injustice is on everyone’s radar. If someone is being harmed in any way, people pull out their phones and it is viewed. How people are treated, how people are mistreated is something that is constantly in the limelight.”

When it came time to assemble the “dream team” to put together the new exhibition’s articles, layout, literature, and overall appearance, a variety of folks threw their hats into the ring, each as important as the people next to them.

Manuelito (Manny) Wheeler, director of the Navajo Nation Museum in Window Rock, Arizona, represented his people both as a tribal member and a museum professional; Holly Houghten, tribal historic preservation officer of the Mescalero Apache Tribe, advised as a representative for the Mescalero people, who escaped in 1865; consultant Tammy Bormann of New Jersey joined the group to facilitate discussions around race and culture; and historian Morgen Young traveled from Portland, Oregon, representing Historical Research Associates, Inc., to advise on the sensitive building of the exhibition.

“The chemistry with this group is there,” Wheeler says. “Half the time, [when] you’re dealing with design and development aspects of exhibits, the chemistry is not there and it becomes very formulaic. … It wasn’t a self-serving group, either, where it was like, ‘Let’s all pat ourselves on the back.’ Everybody understood the importance of this.”

Cortese agrees, and reflects upon her own involvement. When asked how she’s kept the historical narrative a priority for twenty-seven years and counting, she says with a slight smile: “Well, when you start a story, you finish it.”

Talking

After the exhibition team was assembled, says consultant Tammy Bormann of New Jersey-based TLB Collective, it was time to actually meet for the first time. TLB enables dialogue-based development of change processes just like the Bosque Redondo Memorial’s evolution. “My expertise was to facilitate the process,” Bormann says. Her role was to “bring insight around institutional structural racism,” but even the very first steps of this process felt fraught.

For example: Where to meet? Even that question was loaded. The 2005 decision “to build a government building on sacred [land]” made a meeting location “a complex dynamic.”

Bormann continues, “Particularly for the Navajo people, the philosophy, the cosmology, the belief is you don’t return to the place of trauma, because it comes back with you. Yes, tell the story, but I don’t know—build it right on the ground? It’s a tricky dynamic.”

The project that began in 2017 wasn’t the first time this kind of advisory committee was attempted. An advisory group did meet a few times in 2007. “The outcome of that process was there were several recommendations, next steps, educational work, themes that would get embedded into the exhibit itself,” Bormann says. “I produced a couple of reports as a result of that work, and fundamentally we didn’t move forward.” Then, “the leadership of the site changed. The site manager retired. New people came in. There wasn’t funding. It didn’t really go anywhere, for a while…” She pauses. “For a while.”

A while later—ten years later, to be precise—things had changed. The process restarted in 2017 was what she describes as “a nation-to-nation consultation collaborative planning process that wasn’t mandated by the state, but the state participated in with tribal leaders in both communities. Totally different vibe the second time around.”

That vibe led to a swift spirit of collaboration. “There was a sense that learning had to precede planning, and the learning came from the inside out. It wasn’t imposed,” Bormann says. “Because we had more time together and we were funded to be in spaces together, there was an opportunity as a facilitator of the process to build in trustbuilding work, to build in space for really listening and hearing, not just rushing to product. I think that made a difference in the way the group worked together, and the product that emerged and the way the space is now being designed.”

She continues, “In this most recent process, I don’t think the white saviors were in the room. As white folks, we were not absent from that narrative. We just had a different role in that narrative. … This was about accountability and about truthtelling, even in the constraints of knowing that the very existence of the building on the site was problematic.”

A self-described “white girl from the East Coast,” Bormann says, “I do understand the cynicism. I get it. … I think that has been the history not just of that site, but of many historic sites in this country that have been governed, controlled, and shaped by white culture, by white narrative. … If you are an American organization, it doesn’t matter what kind of organization you are—if you were started in this country, then you were planted in the soil of a racialized, genderized social system from the beginning. If you’re American, this is your shit to deal with.”

And deal with it they did.

Returning

“I’d never been there,” Manny Wheeler says of the Bosque Redondo. Wheeler strikes a tall, perhaps imposing figure, and his voice fills the conference room at the Navajo Nation Museum, of which he is the director. “It was something that I had questions about, and it was time for me myself to get some answers.”

In 2017, he was invited by the state of New Mexico to consult on behalf of his tribe about the memorial’s new exhibition. Wheeler grew up knowing what happened in Fort Sumner, but he also knew that, for some members of his tribe, returning to the site is taboo. At the time of the Long Walk, the Navajos were particularly distressed to travel outside the square formed by the four sacred mountains; the change in landscape from the rich red-rock landscape of Dinétah to the flat, bleak llano of Fort Sumner notwithstanding, it was believed that the prayers and traditions of the Navajos would become meaningless outside of their homeland.

Today there is still some resistance to journeying to the Bosque Redondo. When the Navajos left in 1868, the headmen of the tribe vowed never to return to Hwéeldi, and many generations of the tribe regarded that rule as sacrosanct.

“But from an administrative standpoint, as a Navajo Nation employee and as a director of the Navajo Nation Museum, I understood that 2018 was coming up,” Wheeler says, in reference to the 150th anniversary of the Treaty of 1868. “I knew that somebody had to … acknowledge 1868, acknowledge the tragedy, acknowledge the spiritual ramifications that are associated with it.” He continues, “It’s almost like one of those ships that break ice. I had to break the ice first, so that everybody else can start to participate if they wanted to.”

It turns out that more people want to interact with this history than is perhaps realized. “A common misconception is that the majority of Navajo people do not want to go to Fort Sumner,” he says.

Houghten concurs. Of the Ndé, she says, “I would say it’s 80 percent would be for talking about it, and 20 percent not. Another reason for the shift is we’ve lost a lot of our elders who were much more embedded in the culture; and the reason it’s not talked about is because it’s part of the culture not to talk of the dead or of bad things, because it may be bringing them back upon you.” But an evolution of communication within the Mescalero Tribe has contributed, in her view, to a much more willing attitude toward discussing difficult histories.

Wheeler continues, “I’ve found plenty of people, including myself, who have questions and want to contend with that part of Navajo history, part of my history. My maternal grandmother was extremely wise in the ways of Navajo beliefs and ceremonial practices. That being said, she visited Fort Sumner on more than one occasion. She raised my mother with the idea, concept, and belief that we need to be strong because the people who survived that were strong. That, in turn, makes us stronger.”

But appreciating the strength of ancestors doesn’t necessarily mean that busloads of Diné will travel to the Bosque for picnics—or that anyone should. “There’s the other part, for me, the humanistic approach,” Wheeler says. “This is an emotionally, historically, and psychologically heavy location to go to, regardless of your belief system. For a lot of Navajo people, it’s complicated. It’s complicated for us.”

Houghten also appreciated the collaboration before anything was set in stone. “A lot of it is a trust issue,” she says. “They ask you to help, but then a lot of times they develop everything and say, ‘Okay, here’s what we’re doing, is it okay?’ And if you say, ‘Well, we really wish you’d done it this way,’ they say, ‘Well, we already paid to have this done, we can’t really change it.’ Things like that. So this project was better, because they did bring us on from the beginning, and actually had us involved in all the steps.”

In working together to craft the exhibition, Roth recalls one instance that illustrated the tribal consultants’ influence. The Glimpse of Life program was an educational activity presented for inclusion at the site. Roth describes:

Fort Sumner high school kids … were given forty-five minutes to build a home with whatever they could find around the site. Then they were given the same type of rations that would have been issued here. Mind you, it wasn’t rotting or filled with plaster of Paris, but they were given eight ounces of meat, a pound of white flour or cornmeal, some coffee beans, and some sugar. Then they had to make adobe bricks. Then they had a creative writing exercise where they were given a persona of somebody based upon historical fact and they had to write from their perspective. Part of the interpretive plan was expanding that.

I remember talking to Manny outside, and I said, “Manny, how do you think the schools on the Navajo Nation would feel about joining in with the Glimpse of Life program? That we could combine Fort Sumner kids and say a school from the Navajo Nation and mix everybody up and gauge that experience?”

He said, “Well, I don’t really think that’s a good idea.”

I said, “What are your thoughts on that?”

He said, “Well, it would be similar to if you sent Jews to Auschwitz and said, ‘Why don’t you live there for a day or two to see what life was like in Auschwitz?’”

Beyond the complicated history, Wheeler says, there is mostly respect between members of his tribe who differ in their beliefs about traveling to the Bosque. “I also don’t want to paint a picture of, ‘Everything was rainbows, and all Navajos were skipping along together in unison.’ There were also points of ugliness about each other’s belief systems. The majority of Navajos came together, regardless of that, and said, ‘This is an important point of our history, an important time to state that after that tragedy and after that point in time where our ancestors, in 1868, questioned our future.’”

Roth also believes this return is important, whether physically or through education. He says of Navajo Nation President Jonathan Nez, “He said, ‘There are many monsters that plague Navajo Nation. Drug abuse, spousal abuse, kids being lost in the system, and problems with land disputes—all of that stems from this place.’ He said, ‘The fact that we’re not talking about it is that we’re just burying this monster deeper.’”

Now, Wheeler says of the Bosque Redondo, “Every time I go there, I just find a little bit of a quiet time just to go outside and stare at the landscape and try to think about many different aspects of that place. The absolute horror, but also the absolute courage that our people had.”

The Plan

When asked about the thirty-plus-year time span between the letter from the Navajo students to the opening of the new Bosque exhibition, Mary Ann Cortese lightly shakes her head. “How long it took, that means nothing to me. That’s not even a story to me. … It does us no good to go back and dredge up why it didn’t work. It is working now.” She smiles. “Something good is happening.”

That “something good” greatly concerns historian Morgen Young, a representative of Historical Research Associates, based in Portland, Oregon. “I’m a public historian, so that essentially means history outside of the classroom—museums, historic preservation, archives,” she says. “My focus is exhibit development. I love creating exhibits with community members—not for community members, but with them directly. That’s totally what we’re doing at the Bosque Redondo Memorial site. … My brain likes combining the analytical side of research and the creative side of conveying complex history to the public.”

And of course, when it comes to complex histories, Fort Sumner fits the bill. “I knew it was also going to be a challenge of a site that is revered by others for its association with Billy the Kid,” Young says. “I knew that I didn’t want to continue that reverence myself.”

So, she said, she leaned heavily on Wheeler and Houghten as partners from Indigenous communities to craft the exhibition. “We wanted the community voice to be first and foremost. That was how we structured all of the content and the design.” Indeed, she says, in reference to the note found in the rock shrine in 1990, “The whole show starts with that letter. That letter is a challenge to the site to the state of, ‘Why aren’t you telling our story? Our story needs to be here.’”

While there are opportunities to just skim the exhibition and opportunities to dive deeper, no matter what mode a viewer uses to view the memorial, “it’s a heavy exhibit. It is not easy history. We try to give people areas where they can pause and reflect.”

Because the exhibition is so emotionally charged, it’s broken up into stages, perhaps the most challenging of which is a circular room at the center of the building that features contemporary accounts of life at the Bosque read aloud.

It’s a lot to take in—so, Young says, “At the end, there [is] also this reflection room where you’re able to sit and share your experiences, either at the exhibit or as a member of these communities who have dealt with intergenerational trauma. The hope is that the content is presented in such a way that you will get something out of it, whether you read ten words or all of the words.”

The exhibition is unique in that there aren’t many artifacts from the site during the Bosque Redondo era. But the team found ways around it. One display box contains a ration token, illustrating both the struggle to get enough supplies—and the ingenuity of skilled Navajo silversmiths, who quickly learned to counterfeit them. Additionally, to accompany a quote about finding meager mesquite roots for firewood, Young says, “Mary Ann Cortese’s husband Buddy provided us with a mesquite root that he got from his property.” Something as neutral as a piece of wood, in this environment, takes on an intense charge: Picture walking miles every day for roots smaller than this one, hoping against hope it could feed a fire all day and night.

In reference to a cup of cornmeal in the round theater room, lit softly in a glass box, Young says, “You walk up to this seemingly innocuous object and you read this recollection of what people went through at this site.” The cornmeal is presented with an account of young women and girls sexually assaulted in exchange for a meager ration, like what you see in the cup. “That’s us utilizing community oral traditions of what happened there, and then trying to illustrate that with objects [that have an] even bigger impact on visitors.”

For Young, the development of the exhibition was as much a learning experience as it was one of creation. “There were ideas I had on the exhibit and I would run by [Manny Wheeler and Holly Houghten]. They would tell me that they were inappropriate.” She says she appreciated “being able to work directly with them and learn from them and realize how much I don’t know. … There’s no ego with this sort of stuff.”

The Exhibition

The final exhibition, which saw a soft opening to the public in July 2021 and celebrates its grand opening on May 28, 2022, is reverential without being static; it’s informative without being didactic; it’s heavy without being oppressive.

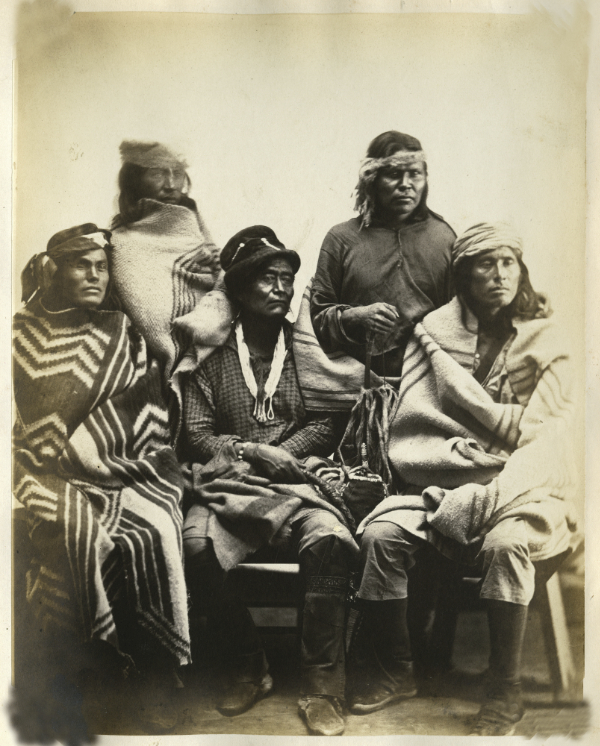

Dressed in cool blues and bathed in the ambient light of a fiber-optic installation hanging overhead throughout the first half of the exhibition, it features mostly historic photos blown up floor-to-ceiling on the walls, along with descriptive text—mostly quotes from Indigenous scholars and historic figures, as well as panels about the site’s history in English, Diné (Navajo), and Ndé (Apache). As previously mentioned, there aren’t necessarily many physical objects in the exhibition, but that makes those on display even more impactful.

In particular, a wool dress in the style of what women would have worn at the Bosque Redondo dominates one of the first areas you see upon entering. In addition to unraveling government-issue blankets to re-weave their traditional clothing, the Navajo at Fort Sumner used wool from churro sheep, the tribe’s prized livestock, to weave fabric. The dress by Ephraim Anderson (Diné) is the first garment made of wool from Fort Sumner’s churro sheep since 1868.

The experience of moving through the exhibition is intense, but manageable. Throughout, the language and presentation of information is both sensitive and informative; it doesn’t cut corners or spare ugly details, but viewers are able to digest it bit by bit. This is due in part largely to the design, which only allows you to see small sections at a time as you move through the exhibition on a single path.

“The designers—they were part of the conversations, too, with our tribal partners,” Roth says. “They had input every step of the way. It wasn’t they were hearing these conversations second- or third-hand. They were taking notes from our tribal partners. … They had a wealth of tools to draw upon to make a lot of these concepts come to life. … Everyone sitting at the table together was probably the biggest change. It wasn’t done piecemeal.”

While the majority of the rooms at the Bosque Redondo Memorial describe the incarceration of the Navajo and Apache people, the exhibition doesn’t end with the signing of the Treaty of 1868. The last portion describes many of the struggles and cultural genocide that awaited Indigenous people after they returned to their homelands, including the boarding school program and forced relocation. Many of these discriminatory practices and policies continue to reverberate.

“When we study and teach enslavement in the United States, it’s like the whole African world begins with the Middle Passage,” Bormann says regarding the need to look at the bigger picture. “Nobody ever pays attention to the fact that there were kingdoms and whole lives and histories long before Gorée Island. That was an important part of this. There’s a whole narrative, and it ain’t over yet. … That became important as a mechanism for teaching Navajo people, Mescalero people, people who are not Indigenous at all, who are coming to visit. We also talked about the fact that the site itself has meaning and implications on a global scale. What happened there continues to happen in the world, and happened multiple other times in the United States.”

The last bit of Bormann’s statement refers to the site’s inclusion in the International Coalition of Sites of Conscience, a group of sites around the world that were home to the worst of human atrocity—and the most remarkable of human resilience. At the end of your journey through the exhibition, near a tasteful reflection area, a display of panels describes other Sites of Conscience around the world. Featured are places such as the Carlisle Indian School Farmhouse, Minidoka National Historic Site, and Manzanar National Historic Site, all of which include a brief description of the site’s history and why it is an important part of understanding the history of the atrocities humans have visited upon each other.

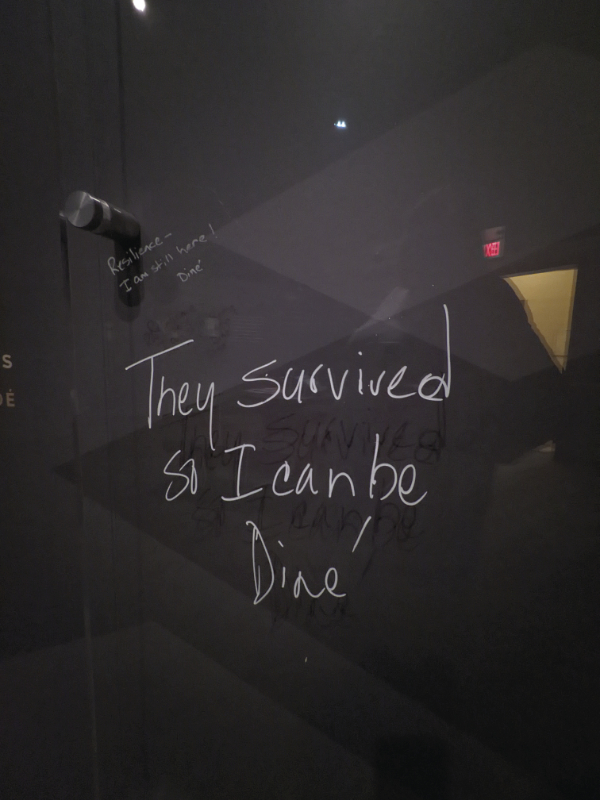

The reflection room, meanwhile, is a comfortable space designed by the Friends of the Bosque Redondo. Earth-toned couches and decorative pillows dot the space; tissue boxes, journals, and pens pepper coffee tables and end tables. It’s a welcoming space to silently reflect, discuss the exhibition with staff or your companions, or recalibrate after an exhibition that could (and should) be jarring. Another room invites visitors to write their thoughts in marker on glass panels.

Most of the reflections, both in the journals and on the walls, are unsigned. Some are in tiny print; some in wobbly writing from a very young or very old hand; others are bold and declarative. In early 2022, right in the middle of one glass panel were stark silver words, the message undeniable:

“They survived so I can be Diné.”

Looking Forward

When asked what the biggest challenge facing the site in the future might be, every member of the team had a similar answer. No one disagrees that the exhibition is world-class, but there is one glaring problem: “Just the physical location of that town,” Wheeler says. “How are we going to get people down there?”

Indeed, Fort Sumner is two and a half hours from either Santa Fe or Albuquerque, and doesn’t fall on any major highway or thoroughfare. Unless there is one large group that has come together, such as a school group, the exhibition rarely has more than a few people visiting at a time. It’s not a huge tourist draw simply because it’s not on the way to or from anywhere in particular.

However, Roth says, “I feel as though there will always be people with ancestral heritage coming here. Because when this place was an open grass field and there was no exhibit, over 3,000 people gathered here. They walked from their homelands to this place in 1968, and it was nothing. Regardless of whether I’m here or anybody else is here, the people will come. It’s important.” He continues: “I know that people will always be here.”

Every member of the exhibition team also had a similar answer to the question of whether the site was “finished.” When asked whether she herself would ever consider her work done, Cortese says no. “When I come back in ten years, if I’m still alive in ten years, I don’t want it to look the same. Absolutely, it shouldn’t. I hope that it just continues to modernize itself.”

Physical location and modernization may not be the site’s only concerns, moving forward. “We live in a time right now that Americans who want to reject or deny the ugliest parts of our history are empowered to do so,” Bormann says. “They are empowered to reject, are empowered to deny, and they’re empowered to express their resistance. I do worry about that in this space. I worry about guarding the hearts and souls of people for whom this is a site of trauma. I worry about guarding that in the face of empowered whiteness in the United States at a time when all of that has been sanctioned and even given nobility.”

While no one on the exhibition team wants to dwell on what hasn’t gone right since the site’s opening in 1971, the missteps and mistakes of their predecessors haven’t been forgotten. “That part is important, owning up to how what was here was not perfect,” Roth says. “It was far from perfect. It wasn’t done well. But after a lot of effort, we’re getting there.”

Continuing

As the sun sets over Fort Sumner, the comfortable heat of an autumn day fades into a brisk dusk. The familiar smooth gradient of a cloudless sky is beautiful, but those well versed in New Mexico weather know it usually means a bitterly cold night is on its way.

While researching this story in October 2019, I took Aaron Roth up on a generous offer to stay a couple nights in a casita on the grounds of the memorial. Roth was almost done orienting me when he remembered one last important point.

“If you hear what sounds like screaming in the middle of the night, it’s okay,” he said. He continued: Some of the churro sheep, which they raise and keep at the memorial, were due to give birth soon.

His ominous warning in my head, I leaned against the casita’s west-facing adobe wall, still warm from the day, and watched the light fade from the sky over the Pecos. I wrote a few words on this piece, read a bit from Hampton Sides’s Blood and Thunder, and mostly sat quietly—which is something everyone should probably do for a while at the Bosque Redondo.

I slept soundly and didn’t dream. The next morning, early-arriving rangers found two little lambs still steaming in the chilly air.

—

Charlotte Jusinski is the editor of El Palacio. She is from New Jersey and has lived in Santa Fe on and off, mostly on, since 2003.

Molly Boyle contributed editing. She is senior editor at New Mexico Magazine.