¡Oye Primos!

Community and resilience in the art of Aztlán

By Petra Salazar

How do we survive the uncertainty of our globalized, techno-digital age? Listen for answers in the sounds and stories of the Borderlands.

The border is not just a geographic location, but something embodied in people who dwell on the border of conflicting identities. In the U.S. Southwest, the region referred to in Chicano philosophy as Aztlán, the border is a place where we find a confluence of diverse Indohispano perspectives, blending Indigenous and Spanish ways of knowing. These ways of knowing remain largely undocumented in the canon of artists and scholars taught in traditional U.S. schools. But those of us who are at home in these borderlands know that our people carry valuable information in our bodies and our styles, our ways of speaking, living, and loving. This knowledge, rooted in our history and our complex racial and sociopolitical identities, is known in Chicano philosophy as “el oro del barrio,” and, if given recognition, it can offer a powerful tonic for coping with the uncertainty of our historical moment.

Indohispano elders have long called for younger generations to claim, steward, and contribute to our inheritance of traditional knowledge. Many young New Mexicans are taking up this call. In her work as a curator with the National Hispanic Cultural Center Art Museum, Jadira Gurulé platforms New Mexican artists whose work puzzles over heritage—never expecting easy answers. Gurulé says the museum has a duty to represent a broad range of Latinx experience. Although there are some themes that frequently arise in the work shown in the museum, including “identity, resilience, healing, family, and community,” Gurulé says that “the beauty in working with these themes is how many ways there are to tell these stories.” She is especially curious about work that explores the museum as an acoustic space.

One such work is by experimental artists Adri De La Cruz and Marisa Demarco. Their collaboration is an expression of a shared interest in documentation and in questions about how knowledge is communicated beyond words, who gets to claim and convey knowledge, and how the audience and environment shape the knowledge that gets conveyed.

The Mountains Wore Down to the Valleys is a multi-phase installation that explores sound as a medium for the transmission of knowledge, through family stories of survival, situated within the acoustic landscape of New Mexico. Demarco describes the work as located at the “intersection of journalism, documenting, storytelling, and experimental sound art.” The installation is intersectional and stages a dialogue between dichotomies—such as sound and story, erosion and survival, grief and renewal. This is a work of the borderlands, one that sheds new light on the uncertain terrain that Indohispano knowledge workers and artists have long been charting.

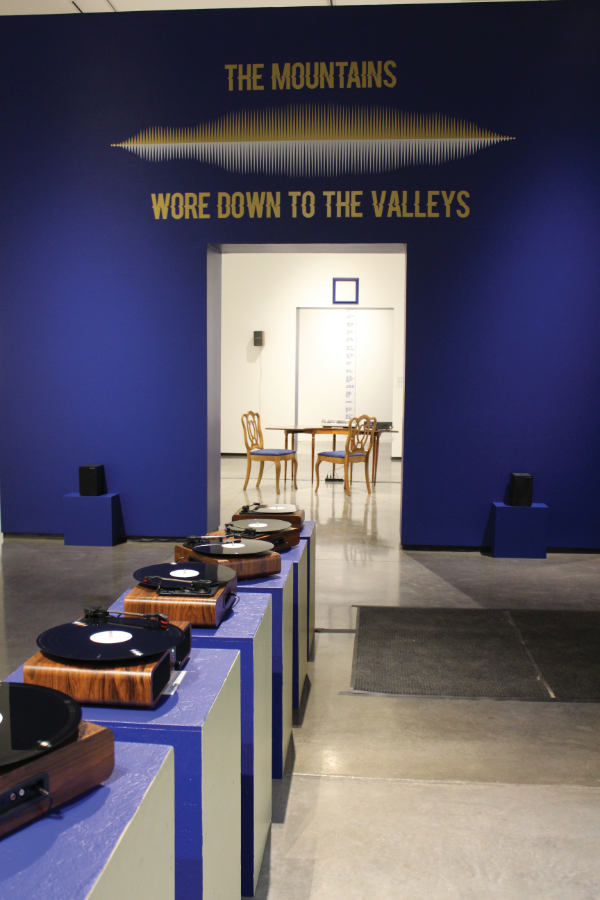

The multi-phase exhibition opened on November 4, 2022. Guests who visited during the first phase, which lasted seventy-two hours, were treated to the full sound experience, amplified by a minimalistic environment. In the museum’s Community Gallery, twenty-one record players are arranged in a row in the center of the space, leading to a small room with one additional record player.

Over the course of the first three days, twenty-two lathe-cut records played simultaneously. Twenty-one of these records played unique musical compositions by Demarco. To my ear, the combined sounds from these atonal compositions evoke New Mexico’s windy, alien desert. The title of each of these records is listed on one gallery wall, forming together a poem about impermanence and resilience. Two tracks, or lines, read:

Uncertainty, rising and falling

Constant, like these hills.

Demarco, a journalist and experimental sound artist, is concerned with the “big long slow changes” that occur in the landscape, unobservable in a single human lifetime. Her work experiments with scale and expanding time. She recently collaborated on a composition representing decades of data on the flow of the Rio Grande.

In the first phase of The Mountains Wore Down to the Valleys, Demarco’s compositions spanned the entire seventy-two-hour period. During that time, the needles from twenty-one record players wore away the ridges, or “mountains,” of the vinyl records, and the sounds from Demarco’s compositions slowly eroded, until they could no longer be heard.

What survived the erosion is a record titled The Mountains Wore Down to the Valleys, which continues to play in the small room. This is the De La Cruz family record, documenting stories from the descendants of migrant farmworkers and the knowledge that helped this family survive uncertain times. In the second phase of the installation, etched portraits of the family were presented on the reverse side of eight eroded records and put on display.

The family record contains el oro del barrio, hard-won insights into the importance of family solidarity, strong mothers, practical skills, and faith in something larger than oneself, like community. Initially, De La Cruz said, their family didn’t feel they had much wisdom to offer. However, through a series of open-ended questions, De La Cruz was able to provoke memories, helping the family summon into words this invaluable traditional knowledge.

New Mexican philosopher Tomás Atencio used a similar form of dialogue to reveal el oro del barrio in his home community of Dixon, where he would facilitate long, open-ended discussions. Afterward, he would organize community action around themes that arose in these dialogues. He called this process “Resolana,” which he proposed as an Indohispano alternative to the Socratic Dialogue. The term “resolana” derives from the Indohispano tradition of men gathering on the sunny side of a home to talk.

The dialogues we hear in The Mountains Wore Down to the Valleys, however, occur at another domestic site of knowledge exchange. In the intimacy of the small room, the family record sits on a table with two chairs. The setting evokes the “kitchen table organizing” described by Joy Harjo and Gloria Bird in the collection Reinventing the Enemy’s Language. They write, “Many revolutions, ideas, songs, and stories have been born around the table of our talk made from grief, joy, sorrow, and happiness.” The kitchen table represents an often unrecognized space of possibility—a space of family dialogue and community organizing.

Dialogue is an oral mode of knowledge sharing that can help us tolerate the uncertainties and complexities of the borderlands and navigate the terrain beyond rigid and reductive colonial boundaries. For his part, Atencio believed that dialogue could reveal universal themes that provide a framework for greater human understanding and relation. Unfortunately, in the current knowledge economy, oral traditions of knowledge production like dialogue have little commercial value. Instead, there is a premium set on knowledge objects—static information, often generated by a single individual and sealed in print, which can be efficiently processed and filed away as documented. This comes at the cost of dynamic and evolving traditions that are impermanent but embodied and alive. When we lose our living connection to these traditions, we risk annihilation.

The Community Gallery is a fitting location to showcase the work of De La Cruz and Demarco, two community-builders who find solace in being just a small part of something greater. During the isolation of the pandemic, the longtime friends leaned on one another and are now rebuilding the vibrant creative community they had before COVID-19. De La Cruz co-runs La Chancla, a hub for experimental artists, and Demarco is a member of the noise collective Death Convention Singers.

While the idea for the installation came before the pandemic, its themes are even more salient now. Preoccupied by digital worlds and relationships, the pressures of wage labor, and polarized demands on binary identities, we’re increasingly alienated from one another, from the Earth, and from our own bodies. The installation’s themes of resilience and community have cross-cultural resonance that extends the impact of the work beyond one family to the broader human family—a family we can choose to recognize.

In many Indohispano traditions, familia has an inclusive connotation: Everyone outside one’s immediate family is a primo, a cousin. This inclusive sense of family accounts for the complex and growing community of people who, despite racial, religious, political, and geographic differences, make up the amorphous family known as Latinos. The presumption of relatedness among Indohispanos leads not only to an inclusive sense of family, but also to an expansive sense of homeland, because primos live all over the Americas and the Caribbean—and wherever there is family, there is home.

We can extend our sense of family even further, the way Demarco scales time. The idea that we’re all connected to each other, and to Earth, can be found in traditional knowledges worldwide. The climate crisis, with its droughts, fires, floods, and displacement, could be seen as a symptom of our forgetting this basic truth.

The installation uses storytelling to activate deep memories, a ritual practice described by Laguna storyteller Leslie Marmon Silko as a key technology that we will need to survive the devastation of forgetting. In her novel Storyteller, she writes: “Old stories and new stories are essential: They tell us who we are, and they enable us to survive. We thank all the ancestors, and we thank all those people who keep on telling stories generation after generation, because if you don’t have the stories, you don’t have anything.”

De La Cruz’s father, who helped the artists build the plinths for the record players, can be heard in one recording urging his child to “keep the life going.” Everyone has a responsibility and a role to play in keeping the life going and sharing el oro del barrio, a duty to ensure we have expressed curiosity in one another’s stories and offered up our own stories. Indohispanos have much to contribute towards a more nuanced, pluralistic understanding of identity, community membership, and querencia—our familial, spiritual connection to land and home.

Experimental artists who work at borders and intersections can help us sit with uncomfortable contradictions, increasing our tolerance to uncertainty. There is much that is uncertain when it comes to climate, heritage, and how we will survive our current historical moment. But as De La Cruz reminds us, “it’s okay to not know.” The knowledge we need to survive is an emergent variable that we are co-creating in dialogue.

While Demarco’s sonic experience has passed, guests can access the eroding sounds via a QR code in the museum. The visual component of The Mountains Wore Down to the Valleys is on display through April 23, 2023, along with the De La Cruz family record, marginalized stories that are worth a listen.

Oye, mis primos.

—

Petra Salazar is a coyote (regional term for an Indohispano/Anglo racial identity) from Española, New Mexico, aka “Spaña.” They teach children at a Montessori school and adults at philopoetics.com. Petra’s work has been published or is forthcoming in Colorado Review, Indiana Review, Sonora Review, The Southampton Review, Latin American Literature Today, and elsewhere.