The Power of One

With a simple act, Miguel H. Trujillo set in motion historic changes for Native American voters

By Stephanie Padilla

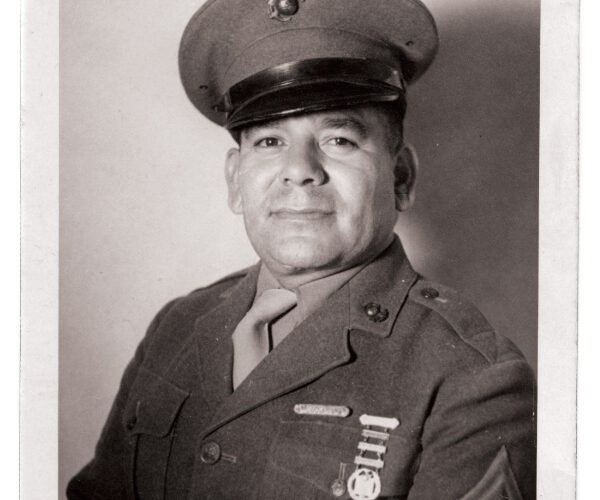

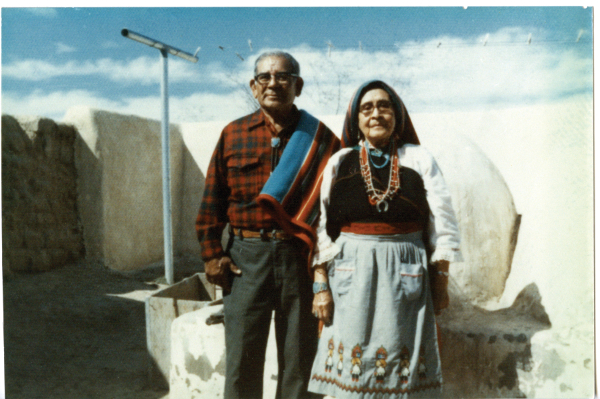

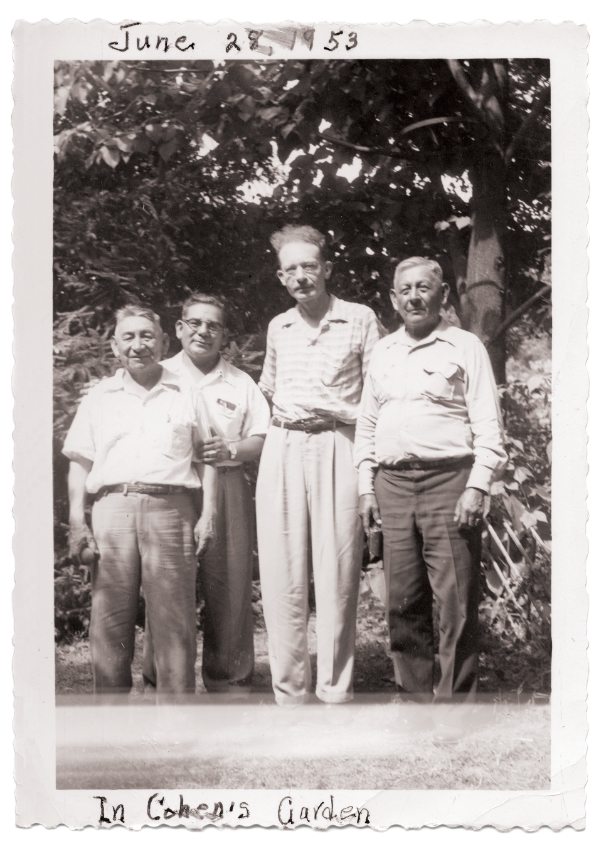

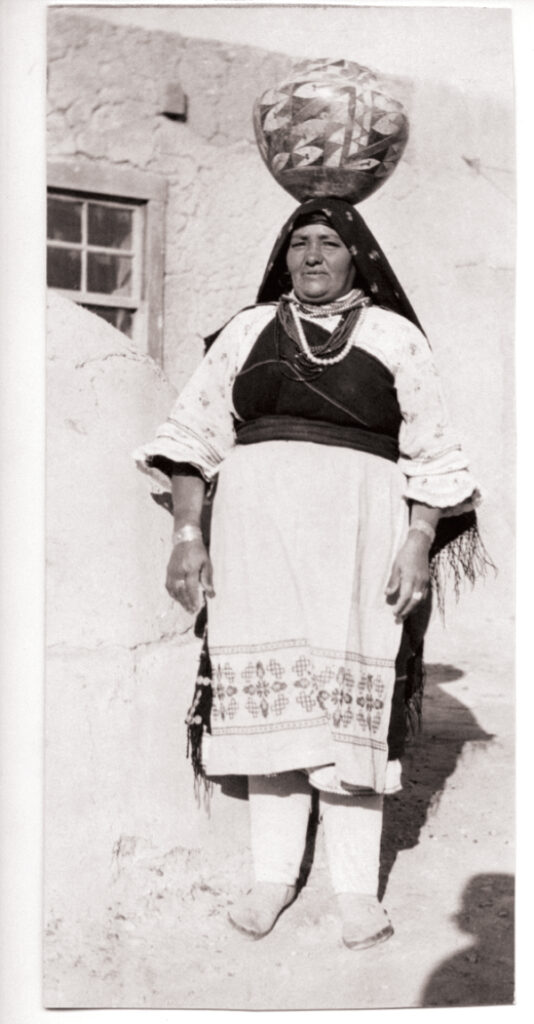

Photographs courtesy Dr. Michael H. Trujillo

In 1948, Pueblo advocate Miguel H. Trujillo and Indian Law attorney Felix Cohen walked into a courtroom and prevailed in their fight to win the Native American right to vote in New Mexico. Despite such a monumental achievement, only recently has Miguel Trujillo started to become a familiar name to the average New Mexican. Outside of the niche community of those who have studied Indian law or voting rights, Trujillo and Cohen are not well known. Without wider teaching and recognition of their actions, students and scholars alike have missed out on an inspiring but controversial moment in history which we continue to benefit from and fight for today.

In 2022, aided by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the New Mexico History Museum embarked upon an effort to bring more awareness to Native American voting rights and their foundation in Trujillo v. Garley, the court case fought and won in 1948. Now, with episodes of the podcast Encounter Culture and a corresponding video documentary series, the NMHM and the New Mexico Department of Cultural Affairs present contemporary takes on longstanding questions related to how the Indigenous people of New Mexico interact with their government.

What is the value of education, and how does a well-educated person interact with their government? How does the United States’ style of governance compare or contrast with an Indigenous model? What loyalty do Native Americans feel to the American government, after centuries of mistreatment and disenfranchisement? How does studying the history of Native American voting and the actions of Miguel Trujillo influence current Native decision-makers and figureheads in their work and mentorship?

To even begin to consider such questions, the first step is to look at the history of Trujillo’s life and advocacy, and how it plays into New Mexico’s Native history.

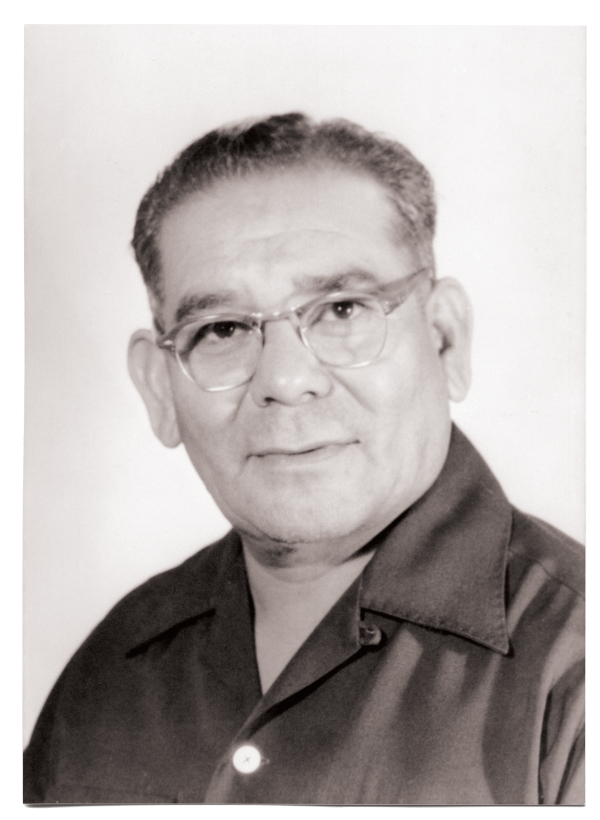

Miguel H. Trujillo (1904–1989) was born and raised in Isleta Pueblo, one of the nineteen pueblos located in New Mexico. He attended Bureau of Indian Affairs boarding schools and the University of New Mexico and eventually enlisted in the Marines, but was passionate about education throughout. While pursuing his education he married Ruchanda Paisano of the Pueblo of Laguna, which is about an hour west of Albuquerque. The couple lived most of their adult lives and raised their children in Laguna. Both pursuing their careers in education, Trujillo became the principal and Ruchanda became a teacher at Laguna Day School. According to their family, they made quite a team; Ruchanda was an organizer and homemaker as well as a career woman, and later would keep Miguel prepared and rested during Trujillo v. Garley. Ruchanda’s attention to detail and unwavering support of her husband’s endeavors were vital to the success of the case.

On three separate occasions, Santa Clara scholar Dr. Porter Swentzell, filmmaker Sibel Melik, and I sat down with Trujillo’s son, Dr. Michael H. Trujillo, and his granddaughter Karen Waconda. Both of them had come to share their memories of their family and what they knew about Trujillo v. Garley. In a cozy room at Albuquerque’s Indian Pueblo Cultural Center, surrounded by white adobe walls and the chirping of uninvited crickets, we listened to each of their stories.

There were five common themes that came up as Michael Trujillo and Waconda spoke of their ancestors: humility, humor, tradition, education, and community. “It’s something that you just do,” Waconda explained after I asked why she thought her grandpa never spoke of his victory. “It wasn’t until twenty years later when I was like ‘Wait a minute, grandpa did that?’”

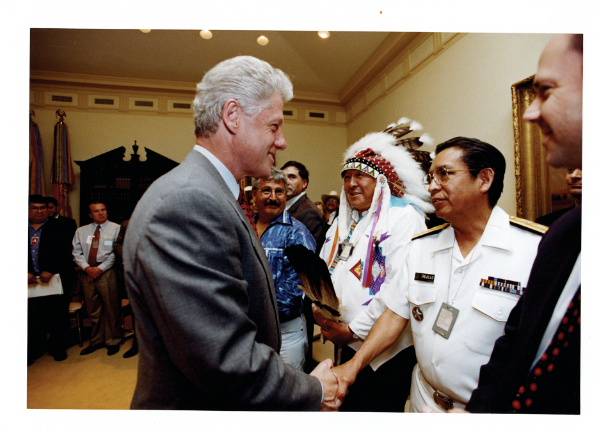

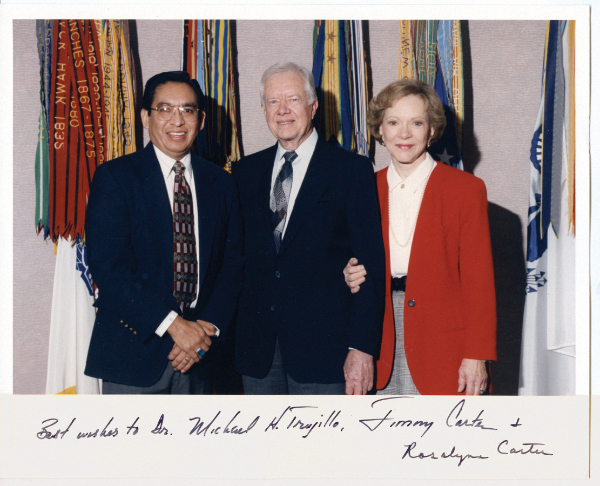

Trujillo rarely discussed his achievements with his grandchildren, but he did educate them on their right to vote and how to execute that right. Waconda remembers when she neared the age to vote, her grandpa drew an illustration of a ballot box, a ballot, and explained how the process worked. “We would watch presidential elections and state elections and he would review it with me and say, ‘Okay, what did you learn from this? What rights are they fighting for?’” Waconda recalls with a smile. Trujillo also emphasized the importance of education and that once you are educated, no one can take it away. This stuck with his children and grandchildren, each of whom went on to be incredibly successful in their endeavors. (Dr. Michael Trujillo was the head of the Indian Health Services appointed by President Bill Clinton.)

Trujillo was deeply invested in education despite the long era of boarding schools, the effects of which he experienced himself. An American education was forced on many children of Trujillo’s age. “He used to tell me little stories from when he was actually taken from his family home at Isleta. … They came around the houses to take children to Albuquerque Indian School and he remembered that he hid underneath the bed so he wasn’t taken,” Waconda recalls. The second time this happened they managed to find and take Trujillo, but he snuck out of the school and walked back to Isleta—a long trek for an adult, let alone a child.

Though resistant at first, Trujillo soon had a change of heart as he began to consider the opportunities an education could bring, despite the often malicious intent behind boarding schools. Trujillo realized he could use the power of education to his own benefit and the benefit of his people. He went on to graduate from Haskell Indian Nations University in Lawrence, Kansas, and the University of New Mexico. Trujillo was a jack of all trades, and during his time at Haskell he participated in a range of hobbies including wrestling and filmmaking.

Upon graduating from the University of New Mexico, Trujillo joined the Marines, where he served as a recruiter for World War II. He recruited a number of Navajo men, many of whom became Navajo Code Talkers. After the war, Trujillo continued to follow his passion for education, becoming the principal at Laguna Day School. We can assume it was his extensive education or possibly his service during the war that pushed Trujillo to be so invested in voting rights. To an extent, these assumptions may be true, but his family believes that it was simpler than that: He didn’t understand why he and his community members couldn’t vote, so he made it happen.

Around the time the case was brought in 1948, voting was still incredibly controversial among tribes in New Mexico. Many traditional leaders were opposed to voting, fearing what it might do to tribal sovereignty; they suspected that becoming eligible to vote on a state level might impact sovereignty on tribal land, allowing encroachment by the state. On the other hand, there were some people, mostly of the younger generation, who had a different perspective. The latter group didn’t understand why they were permitted to stand next to a white man in combat but not in a voter registration line.

Navajo Code Talkers were introduced in World War I. In World War II they returned with twenty other tribes who would use their languages to help the United States prevail. While enlisted in the Marines as a recruiter, Trujillo recruited Navajo Code Talker Thomas Begay from Gallup, New Mexico. At a recent event honoring Trujillo in Isleta Pueblo, Begay chuckled as he told the audience that he had decided to enlist in the Marines because they had the fanciest uniform. Begay ended up doing much more than wearing a fancy uniform—he successfully transmitted 800 messages during the war without any flaws. After a long and successful military career which included service in the Korean War, he received the Presidential Unit Citation with three Bronze Stars, the Meritorious Unit Citation with the Korean Service Medal with five Bronze Stars, and a Congressional Medal from President George W. Bush. Begay was only one of the thousands of Native Americans who saw active duty in World War II, yet he returned home without the ability to vote in an election.

Native-led contributions to the war were monumental motivators to gain the right to vote for many, but Trujillo’s family doesn’t think it was his only or even his main motivator. But Trujillo knew, regardless of the war, that the decisions being made out there would be impacting what would happen here; federal policies orchestrated in Washington, D.C. would only play larger parts in daily life for Indigenous people in New Mexico and beyond. He knew voting rights were vital to the success and independence of Native people and their governments.

Felix Solomon Cohen: The Father of Federal Indian Law

Felix S. Cohen, born in 1907, was a Jewish American from Manhattan, New York. After earning a PhD in philosophy from Harvard and subsequently graduating from Columbia Law School, Cohen was hired by the Department of the Interior. Though he didn’t initially set out to become an Indian Law attorney, he believed deeply in cultural and legal pluralism. Much of this had to do with his upbringing, as debate and critical thinking were encouraged in his household. Toward the beginning of his career, Cohen became sincerely invested in advocating for the interest of Native communities. As a young attorney, Cohen was well ahead of his time and failed to display the widespread ignorance and apathy often directed toward Native people.

Straight out of law school, Cohen served as a government attorney for the Department of Justice, where his primary duty was to contribute to the development of the Handbook of Federal Indian Law. He was later fired from this position (he suspected antisemitism; other historians suggest his involvement would have made the handbook give too much power to Indigenous people, whom the government has historically always tried to subvert). His dismissal put a pause on the handbook, but not Cohen’s work. He had become dedicated to the Handbook, so rather than give up, he finished the job with resources gathered through the Department of Interior, where he had resumed his position as the solicitor. The Handbook of Federal Indian Law is still relevant in the court system today and has been republished several times. During his career, Cohen drafted several tribal constitutions and made meaningful connections with various tribes. There is no doubt that by this point in his career, he was well trusted by Indigenous people across the country.

By 1940, Cohen was serving as the attorney for the Pueblo of Laguna. Aside from being progressively ahead of his years, contemporary accounts attest that he had a great sense of humor and a sincere desire to cultivate lasting relationships with the people he helped. Cohen believed that Indian reservations held a promise for a better national future—a future that would reflect his pluralist ideals. He also did not believe in assimilation, as he knew this would mean the death of the cultures he respected and appreciated.

Cohen was an asset to Native American tribes, and his valuable and dedicated work eventually led him to Trujillo v. Garley. The people of Laguna appear to have trusted Cohen, and he and Trujillo developed a friendship during the case. Michael Trujillo laughed as he recounted one afternoon when he and his family came home to a note from a friendly but hungry intruder. “One day we came home to a note from Felix; he had climbed through the window and helped himself to some bread.”

Trujillo v. Garley

The story commonly told is that in 1948, Miguel Trujillo walked into the registrar’s office in Valencia County to register to vote but was denied by Eloy Garley, who turned him away because Native Americans could not vote in the state of New Mexico. This decision was allegedly based on the New Mexico Constitution, which read that “Indians not taxed” would not be permitted to vote. According to Felix Cohen, however, the problem with this constitutional provision was that Indians were taxed, and so it had no merit.

According to Michael Trujillo, his father and Garley actually knew each other personally, as they had met at UNM. When Trujillo walked in to register, he already knew he would be turned away by Garley—but this was a part of the plan. Being denied the ability to register to vote was what he and Cohen needed to get the ball rolling on the case. So as planned, Trujillo walked into the registrar’s office with his eager attorney waiting for him, and he successfully failed to register to vote.

Trujillo sued, and through Cohen, he argued to the three-judge panel in the Federal District Court that though Trujillo does not pay property taxes, he does pay taxes on everything else including gas, groceries, and income. On August 3, 1948, the judges ruled in Trujillo’s favor, and Judge Orie Phillips made the important point that taxes have nothing to do with the right to vote, and it was in fact a violation of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments that Indians were the only race who must pay taxes to vote.

This monumental moment in New Mexican history was well overdue and mostly celebrated; however, it was soon overshadowed by those opposed to the decision. There were still many New Mexicans who did not believe that the Indigenous population should participate in elections, and pushed to have Trujillo v. Garley overturned. Much of this pushback came from state officials who thought Natives were the federal government’s “responsibility,” and that allowing them the right to vote would confuse this.

Coincidentally, just a few weeks before Trujillo v. Garley was decided, Arizona’s Harrison v. Laveen was decided, also succeeding in granting voting rights to Native Americans. Just like Trujillo, Frank Harrison was a Native American World War II veteran who walked into the Maricopa County Registrar’s office to register to vote. And just like Trujillo, Harrison was turned away because Native Americans were not permitted to vote in his state. The county recorder, Roger Laveen, cited the Arizona State Constitution which stated that Native Americans were considered persons under guardianship of the United States and thus were not permitted to vote. Harrison found this to be unjust and sued, eventually prevailing in the Supreme Court of Arizona just weeks before Trujillo v. Garley was decided. In the opinion issued by Justice Levi Stuart Udall in the decision on Harrison v. Laveen, the judge refers to none other than Felix Cohen’s Handbook of Federal Indian Law, calling the work “monumental.”

Sadly, Felix Cohen passed away in 1953 at the young age of 46—not long after he, Trujillo, and New Mexican Natives celebrated their win in Trujillo v. Garley. Felix Cohen was, and still is, a legendary Indian Law attorney. In his short life and career, he managed to leave behind a firm foundation of Federal Indian Law and an enormous amount of love and respect from the people he served.

The Controversy of Voting

In 1846, General Stephen Watts Kearny’s army entered Santa Fe, New Mexico. Previously, New Mexican tribes had suffered the effects of colonization by the hands of Mexican and Spanish governments. But through a limited amount of sovereignty and independence, they learned how to advocate for themselves. Under Spanish and Mexican governance, New Mexican Natives were considered citizens, and because they were citizens, they had rights.

The United States government, however, did not share this thinking. In the United States’ view, Native Americans were not and should not be considered citizens. In the second half of the nineteenth century, Native Americans everywhere were forced to resist assimilation efforts by the United States and their claims to their lands were at an all-time vulnerability. It wasn’t until 1924 when The Snyder Act was passed that Native Americans were granted citizenship and with that, the right to vote. However, discretion on whether Native people could actually vote was left up to the states, and it wasn’t until the decision of Trujillo v. Garley in 1948 that Native Americans in all fifty states had the right to vote.

Due to the complex and lengthy history of colonial governments, talk of voting rights for Natives in New Mexico and Trujillo v. Garley in the 1940s was controversial. At the All Pueblo Council Meeting held on April 6, 1936, respected Isleta leader Pablo Abeita said, “I hope that I will be seven feet under the ground when my people start voting.” Abeita said this during meetings concerning the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, also known as The Wheeler Act. The goal of the IRA was to push Native American tribes to adopt governments that would reflect that of the United States. Tribes that adopted these governments and created constitutions of their own would receive subsidies from the federal government. Abeita felt that this was yet another unnecessary invasion into tribal governments.

As part of the Department of Cultural Affairs’ podcast series Encounter Culture, Borderlands historian Dr. Maurice Crandall, a citizen of the Yavapai-Apache Nation of Camp Verde, Arizona, explained the traditional process of decision-making in most tribal governments. Rather than vote, the people would have discussions and made decisions only after listening to each other and a consensus was reached. Sometimes it would take days to come to a consensus. According to Dr. Crandall, this was how tribal governments operated most effectively: as a community.

To this day, many Native Americans do not trust the United States government due to the lengthy history of injustice they have experienced. Indigenous communities all over America are still healing from assimilation and colonization. American Indigenous communities continue to have their voices suppressed due to state-mandated I.D. requirements, gerrymandering, a lack of accessible polls, and other voter suppression efforts rampant in communities of color across the United States.

The Fight Continues

Voting equality, education, and high numbers of participation continue to be a goal yet to be reached. Native leaders persist in their efforts for a better future for Native communities by providing their communities the benefit of proper voting education and the tools they need for participation and success. As part of Encounter Culture, Kara Bobroff and Laura Harris shared their knowledge on how we can someday conquer the barriers that keep Native people away from the polls.

Kara Bobroff (Navajo/Lakota) is one of the founders of the Native American Community Academy, an Albuquerque charter school founded in 2007, that allows its Native American students to remain connected to their cultures while in school. In 2020 she served as the deputy secretary of education for identity, equity, and transformation in New Mexico and holds a long history of being a leader in education. Bobroff discussed how we can encourage Indigenous children to become politically involved; her perspective is that knowledge and an open dialogue, along with providing the tools to participate and become involved at their own levels of comfort, seems to be the most motivating.

Bobroff gives an example of this when she recalls volunteering for Moving America Forward. In addition to registering people to vote, she would teach voter education and participate in outreach efforts. In one instance, there was a group of students from Crown Point, Arizona, who wanted to vote. After the forty-five-minute drive it took to get to the nearest voting site, they found out that one of the students’ registrations did not process correctly. Bobroff assisted in resolving the issue on the spot so the student could participate, but she also remembers how this motivated the students further: “Everybody was really fired up. They were like, ‘Man, they were about to violate her civil rights!’ and ‘What can we do about that?’ Well, it’s knowing that process. … When people have that information, they’re more informed and able to speak up and say, ‘This is what I know to be true.’”

Bobroff also emphasizes the importance of recognizing accurate Native American history and identity in schools. This is important to Bobroff, as she was once a little girl going through a school system that lacked awareness. She recalls a “pervasive lack of Native American role models, both in the classroom as well as in the school,” and shares the vulnerability that surrounded being a young Native girl. “At that time, a lot of media in Albuquerque and throughout our state only portrayed Native American people on the news in really negative ways—which, for me, reinforced stereotypes about what it meant to be a Native American. I think that was really, really hard. I remember going through high school thinking that that was something I didn’t want to bring to the forefront, as much as I have later on in my life, because of the negativity that was experienced, both in the community in which we were living, but also within the school itself. There wasn’t a lot of support for Native American identity.”

Bobroff was able to overcome these barriers and prejudiced perspectives, and has now helped to curate a school that not only addresses these issues but also encourages Indigenous youth to be proud of who they are and push them to use their voices for positive change.

Laura Harris (Comanche) is the director of Americans for Indian Opportunity, which was founded by her mother LaDonna Harris, a trailblazing civil rights activist and Indigenous leader. Harris says Americans for Indian Opportunity was founded in the late 1960s to change federal policy as it applied to Indigenous communities. “Their first really big win was [returning] Taos’s Blue Lake to the people of Taos here in New Mexico… and that was the first time that the federal government ever gave back land to an Indian tribe,” Harris says. AIO doesn’t stop at Native policy; it has also worked on issues involving housing, leadership, and education.

Harris grew up in a home that was very politically involved; in addition to her mother’s political activism, her father was renowned Democratic Senator Fred R. Harris. Participating in elections and politics has always been the norm for her, and she believes firmly that it is vital for Native Americans to be at tables where decisions are being made, and that age is no excuse. When asked for guidance on when youth can begin to participate in campaigns, Harris offers, “There’s no age limit. … I started before birth, right?” Her advice for Native people, including youth, is to become involved in a campaign, even if it is simple volunteer work, which can open doors of opportunity. While Harris grew up in a household that cared a lot about politics, she recognizes that not all Native people are raised this way.

Due to the traumas caused by the United States government, there is still some hesitation in Native communities about becoming actively involved in American politics. When asked why Native Americans should care about American politics and vote, Harris’s answer reflected a vulnerable reality for Native Americans:

“It is important that we all participate and learn how the political process works, because it does affect us so much. We retain our inherent right to be self-governing—the United States Congress recognizes that and so does the federal government. But we say, ‘What Congress giveth, Congress can taketh away’—and they have. So, it’s in our own best interest to run for office and to vote for candidates that support tribes and urban Natives. … Native Americans are part of a national trend of apathy. The idea that their vote doesn’t count and that the average person can’t make a difference couldn’t be more far from the truth. The way our system in the United States is set up is that everybody has opportunity to make a difference, and it starts with civic participation in voting.”

So, indeed—the fight continues, but there are inspiring and motivated leaders who only continue to make strides toward voting equality, education, and participation.

—

Stephanie Padilla grew up on the reservation of Isleta Pueblo. She currently serves our New Mexico community as a children’s court attorney and is passionate about civil rights and her culture.

Encounter Culture, DCA’s official podcast, features interviews about Indian Law and Native American voting rights in its fourth season, releasing weekly in Spring 2023. For more information, visit podcast.newmexicoculture.org or search Encounter Culture in your favorite podcast app.