Fragments of the Story: Who was Mary Greene Blumenschein?

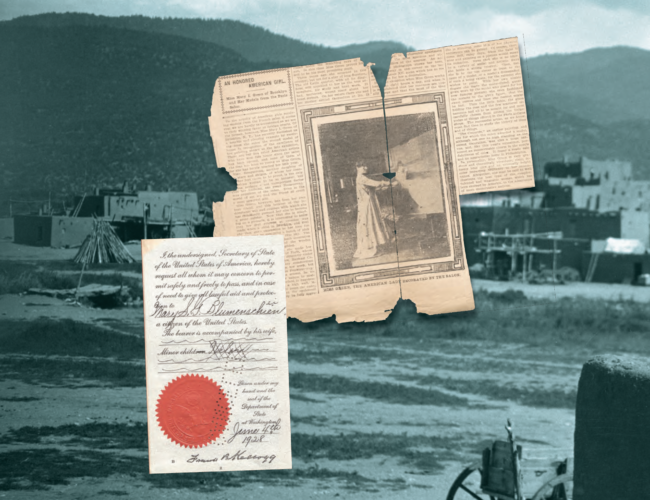

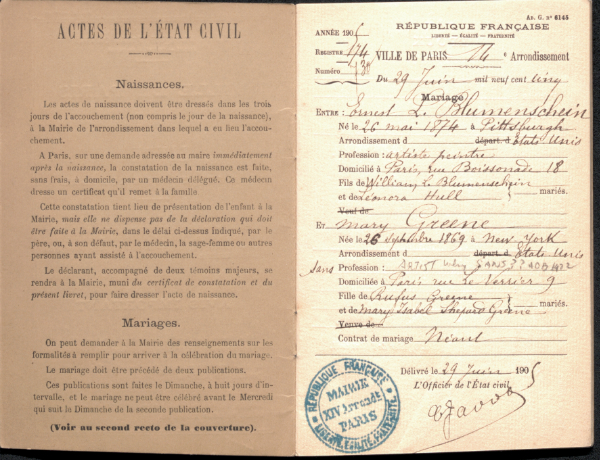

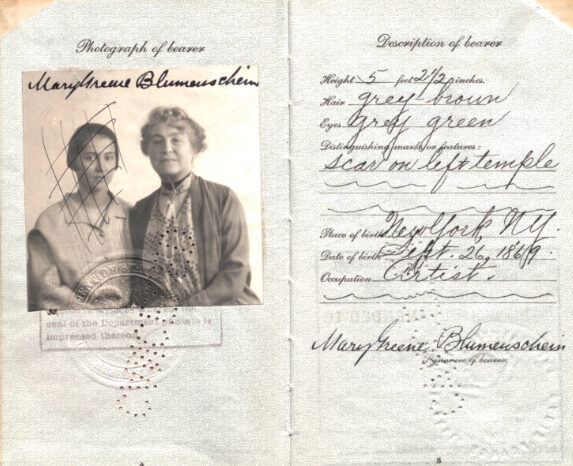

From left: Mary Blumenschein passport page; note Helen’s crossed-out name.

Newsprint, circa April 1902, describing Mary’s second-place prize at the 1902 Société

des Artistes Français Salon. Ernest Blumenschein. All courtesy Blumenschein Family

Collection, Fray Angélico Chávez History Library, New Mexico History Museum. Mary

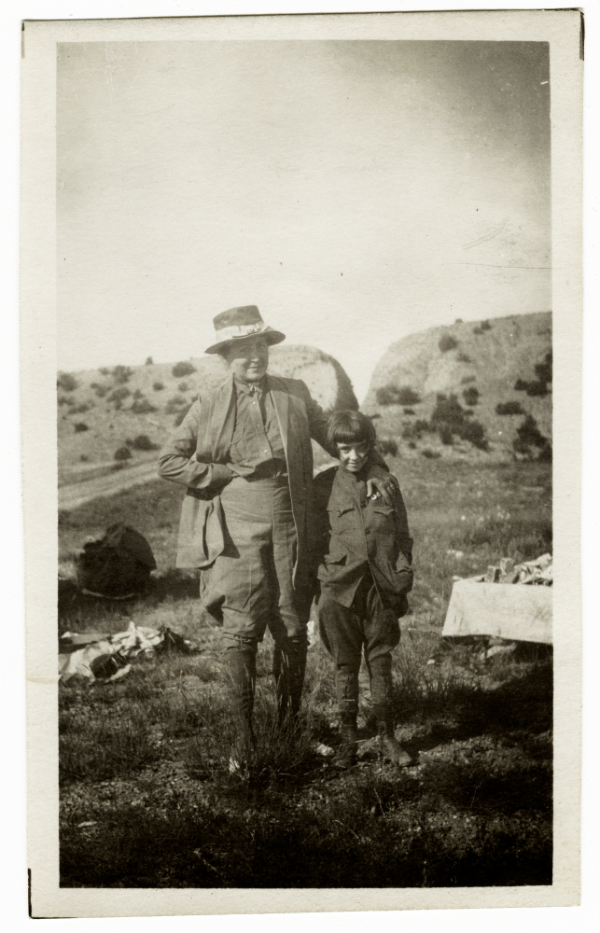

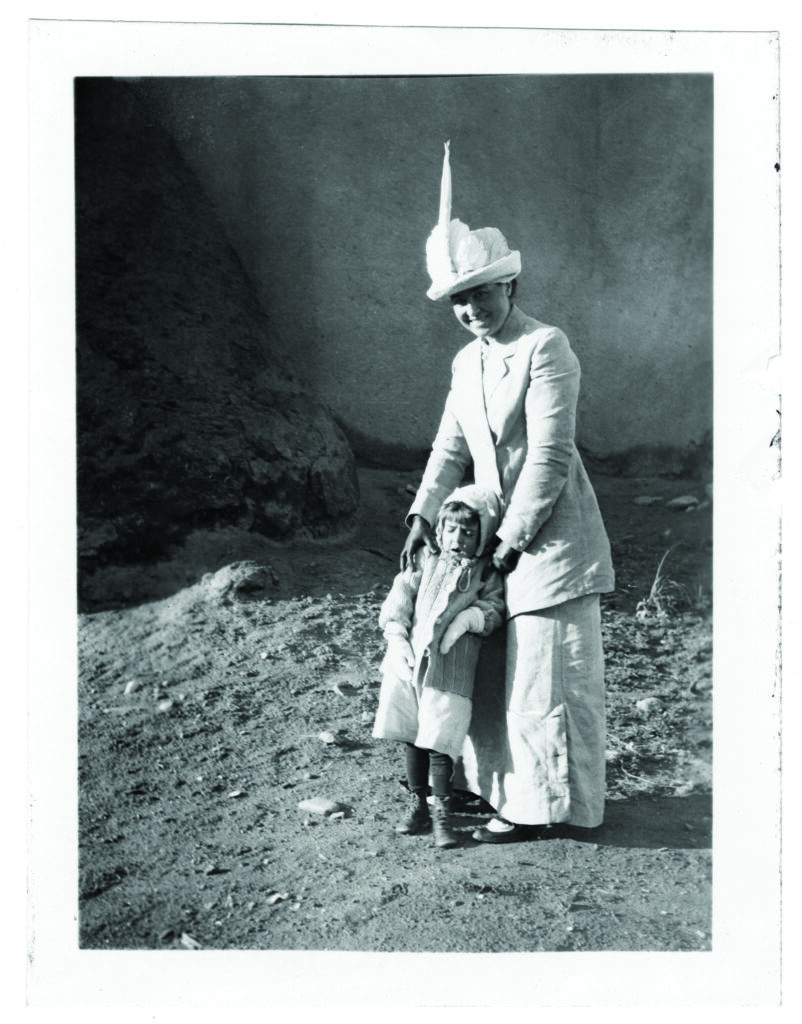

and Helen Greene Blumenschein camping near Kewa Pueblo (Santo Domingo Pueblo),

1919. Courtesy the Helen Blumenschein Collection, Palace of the Governors Photo

Archives (NMHM/DCA), neg. no. PAAC008.002.

Background: Taos scene, image taken between 1899 and 1928. Photographed by

Arnold Genthe (1869-1942). Courtesy Library of Congress LC-DIG-agc-7a01501.

From left: Mary Blumenschein passport page; note Helen’s crossed-out name.

Newsprint, circa April 1902, describing Mary’s second-place prize at the 1902 Société

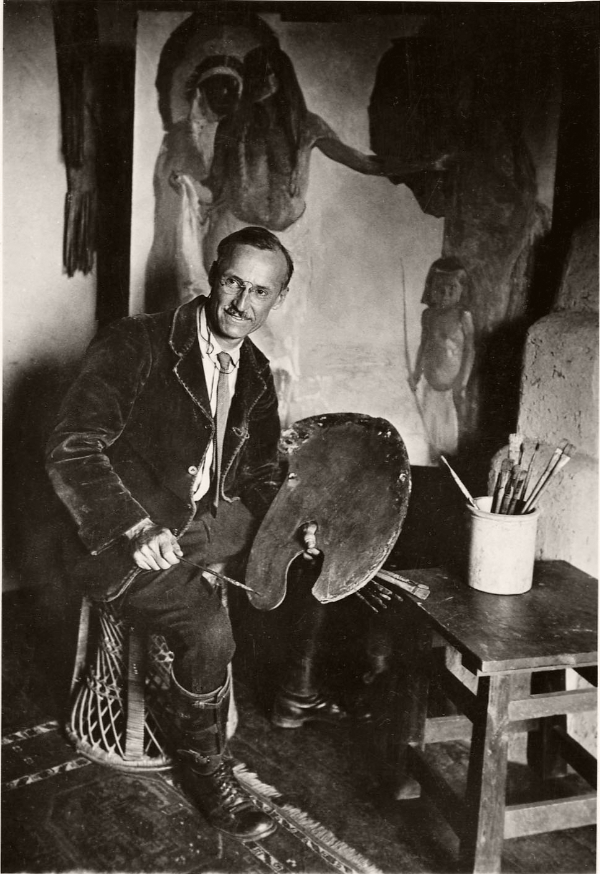

des Artistes Français Salon. Ernest Blumenschein. All courtesy Blumenschein Family

Collection, Fray Angélico Chávez History Library, New Mexico History Museum. Mary

and Helen Greene Blumenschein camping near Kewa Pueblo (Santo Domingo Pueblo),

1919. Courtesy the Helen Blumenschein Collection, Palace of the Governors Photo

Archives (NMHM/DCA), neg. no. PAAC008.002.

Background: Taos scene, image taken between 1899 and 1928. Photographed by

Arnold Genthe (1869-1942). Courtesy Library of Congress LC-DIG-agc-7a01501.

By Marcy Botwick

There are many stories waiting to be discovered at the New Mexico History Museum, particularly those tucked safely away in the archives of the Fray Angélico Chávez History Library. The FACHL houses a variety of materials, from old territorial maps to collections of scientists and writers who lived in New Mexico. One relatively unexplored collection is that of artist Mary Greene Blumenschein, who was married to Taos Society of Artists painter Ernest L. Blumenschein. Both he and Mary helped Taos build its reputation as an art colony, a legacy that continues to this day.

Mary Greene Blumenschein was born in 1869 and lived until 1958. Within her lifetime she witnessed powerful social and technological changes, including the invention of the telephone and car, the advent of the railway and road systems, two World Wars, and rapidly changing roles and expectations for women and men. She lived in Brooklyn, New York City, Paris, and Taos at different times in her life. Her life story and experiences as a working mother, wife, and partner reflect dynamic historical shifts that are relevant and familiar to women and families today.

As evident in items from the FACHL archives, Mary negotiated changing expectations of women over the course of her lifetime. Some changes were based on when she lived, and others on where she lived. In some instances, Mary was at the forefront of new opportunities for women, and in other cases she chose a more traditional path.

I pieced together Mary’s story during visits to FACHL, where I learned firsthand that reading an archive is a bit like excavating and sifting through an archeological dig site. The individual items look like just so much old stuff when you first uncover them. However, when these small shards and broken bits are puzzled back together and fit with additional context, they reveal new ways to understand historical experiences and stories.

I was able to dig deeply into Mary Greene Blumenschein’s archive thanks to the Steve Wimmer Southwest History Research Grant. This fund was established to honor the long-time head concierge at La Fonda hotel, who was a passionate advocate and enthusiast of Santa Fe and New Mexico. The grant was begun in 2021 with Wimmer’s bequest and is still growing through additional fundraising and donations. It provides graduate students or independent researchers with access to the New Mexico History Museum collections to study a person, event, or aspect of the state’s multi-faceted history. It also provides funding and hotel stays at the historic La Fonda so that scholars who do not live in-state can stay during their studies. I would like to thank the museum for this invaluable support in furthering my research.

Mary Shepard Greene Blumenschein kept a tattered piece of newsprint describing her second-place prize at the 1902 Société des Artistes Français Salon for her entire life, though she moved often and did not retain many boxes of memorabilia (see page 62). The photograph shows Mary in front of her prize-winning painting, Une Petite Histoire, in the Paris apartment she shared with her mother Isabel. The article text notes her groundbreaking achievement as one of only a few American women to have won a Salon award at that time, crediting “the indomitable will and courage with which she has steadfastly pursued her aim to become a great painter.” Mary was indeed only the third American woman to win at this most important Salon and was, therefore, in select company.

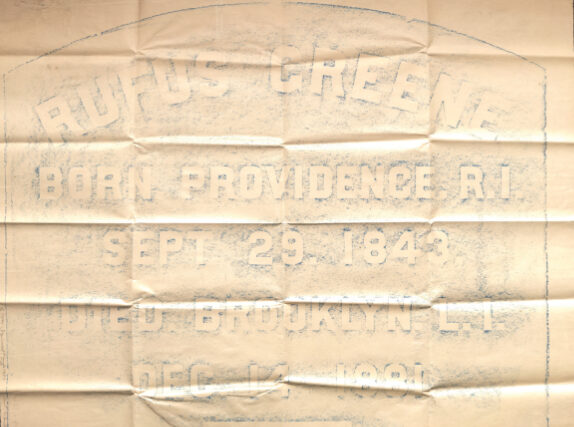

Mary’s parents, Rufus Jr. and Isabel Shepard Greene, were members of Brooklyn’s growing upper class during the Gilded Age, or late Victorian era. She was their only child, born on September 26, 1869, to a home on Van Buren Street. By the time she was in high school, her family had moved to a townhouse at 273 Ryerson Street, a more fashionable section of Brooklyn also called its “Gold Coast.” According to census records and papers in the FACHL archives, her grandfather Rufus Greene was a wealthy importer with a private shipping company. The company sailed barks and schooners to Mozambique, Madagascar, and other East African locations to trade gunpowder for hides, ebony, tortoise shell, ivory, gum copal, beeswax, and red peppers. Mary’s father was part of the family business; he listed his occupation as “African Goods” in the 1875 New York State Census. Unfortunately, Mary’s father died when she was 12, leaving her mother to raise her as a single parent.

A handmade 1889 Class Day Book from Adelphi Academy, where Mary attended high school, is direct evidence of her time at the school and pairs with family anecdotes. Most of Adelphi Academy’s early archives were destroyed by a flood and cannot be consulted to confirm her experiences there. But this small document tells us more than just where Mary went to school; it shows that she was educated at a progressive institution. Adelphi was one of the only coeducational high schools in the New York metropolitan area at a time when most schools were for boys or men only. Adelphi was influenced and supported by forward-thinking leaders including industrialist Charles Pratt, orator Henry Ward Beecher, and publisher Horace Greeley.

Rufus Jr. left a large estate that allowed Isabel and Mary to continue their lives comfortably. According to probate records, Isabel inherited directly, and retained full guardianship of Mary. Isabel was therefore able to manage the family finances without intervention by a male executor, a new recognition of women’s intellect and skill made possible by the passage of the Women’s Property Act in 1848, thirty-three years earlier. Prior to this bill, a man, oftentimes a relative, would have been named executor and Isabel’s access to the inheritance would have been controlled by this outside mediator. Isabel and Mary retained their financial agency and independence because the laws had changed. These same statutes were an important step towards all women’s legal independence and eventually women’s suffrage. The necessity for its adoption and the subsequent fight for women’s right to vote are visceral reminders that women in the late 1800s were not treated as or considered full citizens.

Mary and Isabel were a united mother-daughter team until Isabel’s death in 1917. After Rufus’s death in 1881, Isabel remained unpartnered, and her daughter became the sole focus of her attention. Mary lived with her mother until she married Ernest Blumenschein at the age of 30, and Isabel was an actively involved grandmother to Mary’s daughter Helen. The studio photograph of Isabel and Helen on page 66 was taken the year before Isabel died. In it, Isabel’s clothing clearly marks her identification with the Victorian era and its ideas that women were to always be modest, refined, and chaste.

Victorians felt that men and women were designed as companions, and that their behaviors and attributes were meant to counterbalance each other. Women were responsible for the home and domestic life, and men for roles outside the home, including business and politics. Women were meant to act as taming elements to men’s more competitive nature. Mary was raised in this era and understood some of her role as a woman in its terms. However, social dynamics were shifting by the end of the nineteenth century as a result of laws like the Women’s Property Act in 1848 and the fight for women’s suffrage. Though Isabel taught Mary to be reserved and ladylike, she also showed, by her own example, that women could manage as heads of households coordinating both the finances and the parenting alone.

Mary and Isabel moved to Paris in 1892 so that Mary could continue to study painting. Eleven years later, in 1903, Mary met her husband Ernest Blumenschein at the American Art Association of Paris. Between 1890 and 1922, this social and professional organization was the gathering place for American expatriate artists, one that art historian Emily Burns describes as the “nexus of U.S. art practice in France, a place where hundreds of American artists met and exhibited.”

Art, their identities as artists, and their friendships with other artists remained important to both Mary and Ernest throughout their lives. Their wedding on June 29, 1905 reflected these relationships. A newspaper clipping in the archive describes it as “one of the prettiest weddings the American artist colony has recently seen,” adding a list of guests that highlighted artists Raphaël Collin, Elizabeth Nourse, Susan Watkins, and Frederick Carl Frieseke.

After they married, common work continued to unite Mary and Ernest. Letters and photos show that for the first thirteen years of their marriage, they worked side by side in shared studios both in Paris and New York. From 1905 to 1909, they stayed in France, practicing their painting and advancing their careers abroad. In 1909, they moved to New York shortly before their daughter Helen was born on November 21. In New York, they maintained their affiliation with other artists as active members of the National Academy of Design, a prestigious organization where members could participate in exhibits and compete for prizes. Ernest also helped to found another renowned artist organization in 1915, the Taos Society of Artists.

Their marriage license (page 67) is fairly standard with the exception of the question of Mary’s “Profession,” which has the word “Sans” handwritten before it. The penmanship on the form does not match either Mary or Ernest’s hand, so it was likely written by the clerk in the civil office where they were issued the license. Did the clerk assume Mary was not working and it was not corrected? Why would Ernest or Mary have left out her profession as an artist? Enough women worked outside the home that the form had a specified place for their profession. Unfortunately, it is hard to decipher now why Mary’s work is not credited to her on this license. Helen also noticed this discrepancy and clearly questioned it as she sorted through her parents’ papers. Note the short sentence in pencil in the line where Mary’s profession should have been: “ARTIST why SANS?? HGB 1972.”

Mary and Helen took their first trip to Taos, New Mexico, in 1913. They set off on the long journey from Brooklyn to visit Ernest, who was spending his fourth consecutive summer there painting and sketching. There were a few possible train lines to the Southwest then, all of them long and difficult, and none went to Taos directly. The steep Rio Grande Gorge and mountains made it too difficult to lay track and cut the route. Research has not yet revealed which train line Mary and Helen took in 1913, but it is certain that it took several days on the train. Other photographs in the archives show that they finished the trip by stagecoach. This took another day of travelling rough dirt roads through canyons and passes before arriving in the front range of the Sangre de Cristo mountains.

By 1913, Ernest Blumenschein was already deeply attached to the town of Taos; he had dreamed of moving there since his first visit in 1898 with fellow artist Burt Phillips. Blumenschein wished to create an Anglo artist colony in the Native and Hispano town. He wrote of his initial life-altering experiences there in a May 1926 article in El Palacio titled “Origin of the Taos Art Colony,” commenting, “No artists were here then. No artists were in Santa Fe. It was 1898. And in that year, we two rovers who had met in Paris at the Académie Julien, decided that we had found what we had traveled long to reach.” Blumenschein described his “first powerful impressions” of “the vastness and overwhelming beauty of the skies; terrible drama of the storms; peace of night—all in beauty of color, vigorous form, everchanging light.”

As much as Ernest loved New Mexico, Mary remained unsure, and the 1913 trip was ultimately a failure. Mary and Helen stayed in Taos for only one week. The family story, as told in Helen’s autobiographical book Recuerdos: Early Days of the Blumenschein Family, is that her mother was concerned about a diphtheria outbreak, was unhappy with lodging in a boarding house, and was worried that they had little access to fresh milk or vegetables. I would suggest that Mary’s stated concerns masked a more complicated response, which can be seen in the photograph on page 65.

Looking at the picture, one would never guess that Mary and Helen had recently taken a long difficult trip to a remote place. Mary is immaculately, if inappropriately, dressed in a beautiful white suit, including a large feathered hat. Her clothing seems an odd choice to visit the dust and heat of the mountains and high desert.

Mary had no doubt heard much about Taos from Ernest, but this picture reveals what she had not heard or understood about the remoteness of the town. Ernest may have relayed the beauty of the place, but perhaps not its cultural distance from the life to which she was accustomed in large cities like Brooklyn and Paris. Few letters or documents have yet been found to reveal their feelings about the 1913 trip; however, two subsequent events provide strong indications of her complete discomfort. First, Mary was willing to undertake the very long, difficult journey back to New York City only one week after arriving for what was expected to be a longer stay. Second, though Ernest spent more time in Taos each year after 1913, Mary and Helen did not visit again until the summer of 1919, six years later.

What was Mary doing with her time in New York and Brooklyn in the years between 1910 and 1919? She was raising Helen with Ernest, or as a single parent during his months in Taos, and she was working with increasing popularity as an illustrator and painter. These ten years, when Mary was between 40 and 50 years old, were her most financially successful as a working artist.

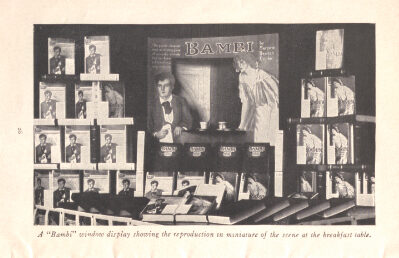

In 1914, the year after the failed trip to Taos, Mary illustrated an internationally best-selling book: Bambi by Marjorie Benton Cooke. The novel was first released as a serial in American Magazine between April and October before being published by Doubleday, Page & Co. later that same year. Mary created thirteen illustrations for the magazine version, nine of which were reprinted in the first edition of the book. Bambi was translated into Danish, Swedish, Finnish, and Spanish, and later editions and translations contain many of those pictures.

The brochure created to promote the book shows a bookstore window display featuring Mary’s illustrations of the main characters, Bambi and Jarvis. The brochure names Mary as the illustrator and describes her work as “some of the best color drawings we have every had for a story. Everyone is delighted with them.” Though couched in vague complementary advertising language, Mary’s inclusion in this brochure highlights the important role of the illustrator in selling popular literature at that time.

Marjorie Benton Cooke’s written works and Mary’s artwork reveal a similar understanding of women’s place in the professional world in the early twentieth century. Benton Cooke, like Mary, was a well-known cultural figure during her prime whose work is not studied or interpreted now. From 1903 until her untimely death in 1920, Benton Cooke wrote twelve novels, four plays, and one book of poetry. Four of her works were made into silent films. She was also a popular speaker who performed monologues on women’s right to vote and wrote articles for the National American Women’s Suffrage Association. Her stories, including Bambi, were popular for their light and humorous tone and for the way they examined relationships between men and women.

While Benton Cooke was an avowed first-wave feminist, feminist ideals in the early twentieth century were fundamentally different than women’s rights movements later in the century. Both Benton Cooke and Mary understood themselves as “New Woman,” a phrase widely used then in magazines, movies, books, and other locations of popular culture. It adapted Victorian feminine ideals of purity, gentleness, and domesticity by adding expectations of professional and/or academic accomplishment to them. Mary spells out her understanding of gendered standards in a May 1915 interview for Every Week Magazine:

Perhaps it is true, as many people assert, that women’s work is less daring and strong than men’s; but at the same time it is certainly more personal, spirited, and decorative. I believe there is such a thing as the woman’s point of view. Women see different things than men, and they see them differently. Women are not exactly more sentimental; but they are sentimental at different moments and for different reasons.

Being “spirited,” “decorative,” and “sentimental” were all considered attractive female traits, while men were valued for being “daring and strong.” Similarly, Benton Cooke’s heroine Bambi was praised by contemporary critic Grant M. Overton for “gayety, courage, tenderness, wit.” Both Mary and Benton Cooke understood that their skills and accomplishments were meant to remain within a woman’s sphere. Mary finishes the interview with a statement that defines her artistic scope as focused on the female: “Personally, I love to paint young and pretty girls: not the merely ‘pretty girls,’ but the ideal American type of young womanhood, compounded of audacity, intelligence, and charm.”

Mary and Helen finally returned to Taos in 1919, when Mary was 50 and Helen was 10. A series of letters between Ernest and Mary document the planning and aftermath of this trip. The letters, held in the Smithsonian Archives of American Art, also provide insight into the Blumenscheins’ relationship fourteen years into their marriage. The letters read like today’s emails and text messages; they are personal and intimate. Dramatic world events, like the 1918 flu pandemic and World War I, are rarely mentioned, though those events clearly formed an important backdrop against which the Blumenscheins’ lives unfolded. A letter from Mary to Ernest might begin with news of Helen’s grades, then discuss visits to the National Academy of Design, and then finally consider practical issues of trip planning and finances. The two often said how they missed each other’s company, and they addressed each other as “Best Beloved” or “Ma Cherie.” Some communications were breezy and light in tone while others, particularly the negotiations about the 1919 summer trip, were clearly more fraught with hopes and expectations.

Since 1910, Ernest had spent his summers in Taos. In 1919, he moved to Albuquerque in January to spend the rest of the winter painting in the Southwest. He lived at the Alvarado Hotel, writing to Mary that it was “a corking good hotel run by Harvey—and the meals are A1.” In March, he bought the family’s first car so that they could go camping that upcoming summer. Ernest’s excitement about both the car and trip is palpable in a March 3 letter where he writes, “I have bought a Ford!! and feel tremendously important,” adding, “I will begin to learn to handle same, in a day or two—and by May 1st, when I hope you will join me, I should be a pretty fair driver.” He then explains in detail what clothing Mary will need for camping and life in Taos. Given Mary’s priorities and choices in 1913, these instructions can be seen as important advice.

The camping outfit [for the car]—tent, mattresses, cooking utensils will probably cost another $50.00 but Albuquerque can supply everything we need. Get your khaki colored riding suit in B’klyn. You can get a ready made one and have it altered to fit you. Get a good warm sweater apiece for nights are cool even in August. … Don’t bring too many changes of clothes, except for Taos, when you may care to dress. For while travelling in the Ford we’ll not change our outer garments except on Sundays!

The photograph on page 63 shows that Mary followed his advice for this trip. She is wearing the recommended “khaki colored riding suit” with a small straw boating hat for sun protection, rather than the formal white suit and large hat of 1913. Mary smiles sideways at the camera looking bemused, hand on her hip as if daring the photographer, presumably Ernest, to take that casual snapshot of her dressed in pants. Though she never did learn to enjoy the rigors of camping and the outdoors, during the summer of 1919, Mary did learn to love life in the town of Taos.

In August 1919, Ernest and Helen went on a second camping trip while Mary stayed in town. This father-daughter excursion was the first in a lifelong series of summer camping and sketching expeditions. Between 1922 and 1929, Mary and Helen spent their winters in Brooklyn where Helen attended school but when they came back to Taos in spring, Ernest and Helen would take off for the mountains and streams. Even into Helen’s adulthood, she and Ernest would spend time together camping, fishing, sketching, and adventuring in the outdoors while Mary rested in their home in Taos. Mary sent a note with food and other supplies to Ernest and Helen’s campsite on August 2, addressing them as “Ernest and Pucker Doodle” and describing how much she was enjoying her time alone. She wrote, “I am going to the hotel for my meals and am having a quiet and restful day. … I feel quite like an unmarried lady without husband and child.” In Taos, she was able to relax and find respite from her busy city life. The small town became a place where she could, as the family referred to it, “hibernate.”

Mary faced family and career complications after Helen graduated from the Packer Collegiate School for Girls in 1928. Rather than go to college, Helen chose to follow in the footsteps of her parents and study art in Paris. Mary chose to act as her daughter’s escort and chaperone in Europe, as had her own mother Isabel in 1892. Mary’s passport confirms details from their time in Europe and shows how male-centered expectations influenced standard practices in the passport process before 1930.

Stamps in the passport show that Mary received the original visa to live in Paris on December 6, 1928, for both herself and her daughter. Helen was still considered a minor in 1928, and therefore did not need a passport of her own. In the 1920s, after WWI and as a result of pressures from the League of Nations, passport processes were in flux as different entities sought to establish international standards for identity papers. The seal impressed into the bottom of Mary and Helen’s picture was indeed a new security requirement begun in 1928. The cross-hatching through Helen’s name on page two (see page 62) and her image on page four (see right) reflect changes to Mary’s passport as a result of Helen turning 19. Marks in the passport on page six show it was officially amended to reflect Helen’s aged-out status on August 24, 1929.

According to Craig Robertson, author of The Passport in America, joint passports for married couples were standard practice before WWI. Before 1920, children, and even servants, were also considered part of a man’s household and did not need their own documents when travelling as a group. This practice maintained the false convention that women did not travel alone without a husband or other suitable male relative. Post-WWI, passports were less restrictive but still demonstrated Victorian assumptions of men’s primary role as the public representative of the family.

Mary’s passport from 1928 shows that a husband could sign on behalf of his wife, implying that a married woman was still considered part of a male household rather than an individual when travelling with her husband. That passports were still family-based for minor children is also shown in the amendments to Mary’s document. Until 1925, married women were also required to use their husband’s surname on their passport even if they did not do so in everyday life. Feminist activists including journalist Ruth Hale, anthropologist Margaret Mead, and aviator Amelia Earhart objected to this practice, creating a national debate about the legal implications of women’s surnames. By 1925, married women had gained the right to use their maiden names, though official practice required that it be followed by the phrase “wife of.”

Mary avoided that dilemma, as she had used both surnames—Greene Blumenschein— since her marriage to Ernest in 1905. She signed paintings created after she was married with either her full name or MGB. From our perspective, this choice may seem small, but in 1905, it was a departure and sign of how Mary felt about her career and status as a working person. In contrast to the marriage license and even though her career was diminished by 1928, Mary noted her occupation as “Artist” in the passport—a signal that she still considered herself a professional artist.

Mary and Helen lived in Paris from December 1929 until April 1931. Ernest visited them for a trip in 1930 when they travelled to Germany to meet extended members of his family. Mary had virtually stopped painting between 1920 and 1929, focusing instead on supporting Helen in school and learning to make jewelry. Mary continued to focus on Helen in Paris, ensuring that her daughter learned art in the Beaux Arts tradition. Helen studied at the Académie Julien, where her father had studied in the late 1800s. While abroad, Mary took up sketching and painting again, inspired by her daughter’s lessons.

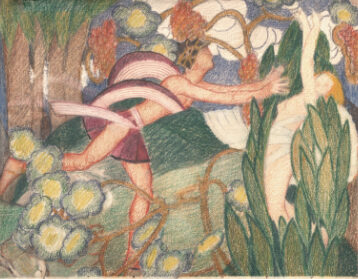

In 1931, Mary finished a large project titled Daphne and Apollo that is a stark departure in style from her earlier illustrations and paintings. In scale, it is one of her largest and most ambitious works, measuring approximately six feet wide by four feet tall. The painting was cut at some point, and the right side of it, featuring Daphne, is now framed and hung at Taos’s E.L. Blumenschein House and Museum. Why or when the painting was cut and what happened to its other section is still being researched. The image above, found during a December 2022 visit to the FACHL archive, is the first published that shows the entire picture.

From 1922 to 1929, Mary learned to make jewelry and studied gold and silversmithing at the Pratt Institute. This work changed her painting style. Tracings and pictures show that her jewelry was influenced by the Art Deco movement, Egyptian archeological finds, and Native American design. In this painting, she translated these styles to canvas depicting bold, simplified, and flattened shapes. The subject matter for the painting was not new to Mary but was a return to the myths and fairy tales that had long held her interest. The painting shows the moment in the Greek story of the river nymph Daphne when she is turned into a laurel tree by her father to avoid Apollo’s amorous pursuit.

Mary returned again to mythic stories in several works painted after 1931. In 1932 she painted Acoma Legend, which also displays a flattened mural style. It is based on a Pueblo story of how the courtship and marriage of Cochin, a beautiful Acoma woman, caused winter and summer, two opposing forces of nature, to form the truce that we now know as the seasons. (Acoma Legend is owned by the Albuquerque Museum and can be seen in its online collection at albuquerque.emuseum.com.) When she was in her eighties, Mary created a set of illustrations for One Thousand and One Nights (also known as The Arabian Nights), which were never published but are also displayed at the museum.

Piecing together and interpreting items from Mary Greene Blumenschein’s archive is part of a larger, more complex biographical project; however, even this brief introduction helps shed light on her individual experiences and those of other women who combined careers and families in the Victorian era and the early twentieth century. Professional women, like Mary and Marjorie Benton Cooke, were in constant negotiation with gendered expectations and limitations; those with children had additional tensions balancing jobs and family. While not singular, Mary was one of few women in the early twentieth century who, in part because of her many privileges, could choose to have both a career and a family. Her experiences show that combining the domestic and the professional was and always has been challenging. They also show that in all of these complicated dynamics, some families who lived one hundred years ago mirror those of today far more than one might expect.

Archives like Mary’s help us understand the history of why we have different expectations for men and women. They contain remnants of experiences that are both different from and similar to our contemporary moment. Old passports, imperfect snapshots, and faded newspaper clippings can seem like unimportant stuff, but they are tangible reminders that lived experience is not linear. Timelines overlap and real lives are messy and complicated. Photographs and ephemera act as idiosyncratic texts that help us see individual lives within a context of larger social patterns, values, and trends when examined closely and purposefully interpreted. The items archives protect reflect both the small and large historical moments that influence and help us understand our lives and experiences today.

—

Marcy Botwick is currently a librarian at the University of New Mexico. Like Mary, Marcy also emigrated from the New York area and maintains strong connections both here and with her eastern roots.