Turquoise at Ogapogeh

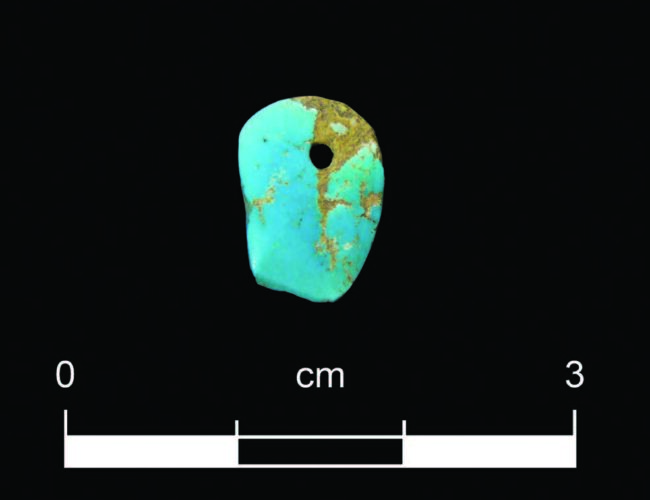

Turquoise ornament recovered from Ogapogeh Pueblo during the excavation prior to the construction of the Santa Fe Community Convention Center. Photograph by Scott Jaquith, Office of Archaeological Studies.

Turquoise ornament recovered from Ogapogeh Pueblo during the excavation prior to the construction of the Santa Fe Community Convention Center. Photograph by Scott Jaquith, Office of Archaeological Studies.

BY MATTHEW J. BARBOUR

In October 2008, the Santa Fe Community Convention Center opened at the northeast corner of Grant Avenue and West Marcy Street, just a few blocks north of the plaza. The property has a long and vibrant history.

Prior to the Convention Center, going backwards in time, the property housed the Santa Fe Civic Center, Santa Fe High School, portions of the Fort Marcy Military Reservation, portions of the Spanish presidio, and a large Pueblo village. To the Tewa-speaking Indians of Tesuque Pueblo, this village is known as Ogapogeh—the White Shell Water Place.

Following state law and the Santa Fe Archaeological Ordinance, before construction could begin on the property, archaeologists were required to document what remained buried beneath the earth. This task fell to the Office of Archaeological Studies, a state agency within the Department of Cultural Affairs. Over several years, archaeologists excavated numerous foundations, privies, and wells associated with Fort Marcy and the Spanish presidio, as well as pit structures, hearths, and refuse pits associated with Ogapogeh.

Excavation of Ogapogeh suggested a village occupied, at least intermittently, from about AD 900 to 1450, encompassing the time known to archaeologists as the Late Developmental, Coalition, and Early Classic periods. Among the artifacts recovered were black-on-white and glazeware pottery, flaked- and ground-stone tools, animal bone, and over 100 turquoise fragments from formal ornaments to raw material and manufacturing debris. Of particular note were sixteen turquoise pendants in trapezoid shapes and four round turquoise beads. The beads were relatively uniform in size and shape and may have come from a single necklace.

Turquoise was found in a wide variety of contexts, including debris pits, burials, and religious structures known to archaeologists as kivas. The discovery of turquoise in ceremonial contexts suggested that the material was of some intrinsic value and may have been used in rituals. However, archaeologists continue to debate the notions of “secular” and “sacred” in Pueblo society; many argue that all aspects of Pueblo life contain some aspect of ritual and ceremony.

The area closest to Santa Fe where turquoise can be collected is in Cerrillos Hills, about thirty miles to the south. Anthropologists working in the early twentieth century noted that only certain tribes were allowed direct access to the turquoise mines, including the Keres-speaking Pueblos of Santa Ana, Santo Domingo (now known as Kewa), Cochiti, and San Felipe, and the Tewa-speaking Pueblos of San Ildefonso.

It is believed that some of the inhabitants of these modern Pueblo villages once occupied San Marcos Pueblo, just north of Cerrillos Hills. Based on San Marcos pottery found in the mines and a few Spanish archival documents, archaeologists believe San Marcos controlled access to both turquoise and lead in Cerrillos Hills from about AD 1300 to 1700. After the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, San Marcos was abandoned, and the villagers fled to these other Pueblo settlements.However, San Marcos may not have monopolized the turquoise mines of Cerrillos Hills before the fourteenth century. Excavations at Pindi Pueblo, a Santa Fe–area village contemporaneous with Ogapogeh, uncovered a turquoise workshop specializing in the production of beads and pendants. While no turquoise workshop was discovered during archaeological investigations at the Convention Center, the presence of both raw turquoise and manufacturing debris strongly suggests the fabrication of turquoise ornaments at Ogapogeh. This emphasis on turquoise manufacture in the Santa Fe area indicates that the inhabitants of Pindi and Ogapogeh had or even controlled access to the Cerrillos Hills mines before the 1300s. Moreover, it is possible that the inhabitants of these Santa Fe pueblos moved south in the fourteenth century to help found San Marcos and perhaps other large, nearby villages in Galisteo Basin.

All of these notions—the manufacture of turquoise ornaments in the Santa Fe area, the ancestral ties of Tesuque to Ogapogeh, the early 1900s ethnographic work which concluded that access to turquoise was relegated to a small number of Keres- and Tewa-speaking Pueblo villages, and control of Cerrillos Hills by San Marcos after AD 1300—have ramifications for the history of the settlement and abandonment of northern New Mexico by Pueblo peoples. Underlying the distribution of turquoise at Ogapogeh and elsewhere is a complex narrative that archaeologists may never fully understand. Yet, the materials found at the Santa Fe Community Convention Center demonstrate the value of turquoise to Pueblo people and its importance in the Santa Fe region as a whole.

Matthew J. Barbour is the manager of Jemez Historic Site in Jemez Springs, New Mexico. He was formerly an archaeologist with the Office of Archaeological Studies.