David Bradley: The Postmodern Trickster

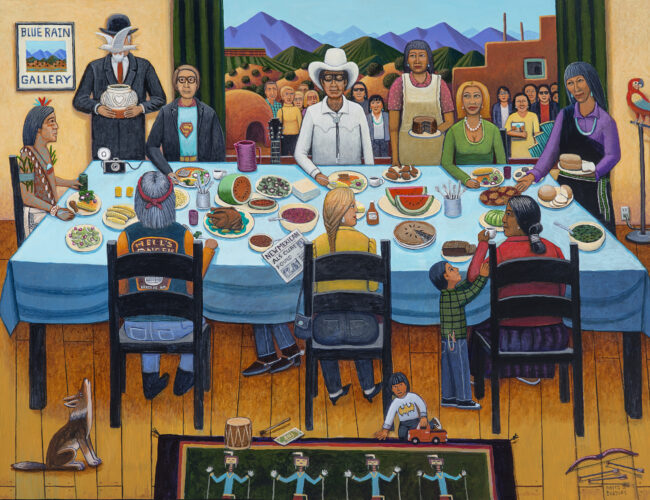

David Bradley, Pueblo Feast Day 1984/2014, Full Circle, 2015. Mixed media, 40 × 60 in. Collection of the artist. Photograph by Blair Clark.

David Bradley, Pueblo Feast Day 1984/2014, Full Circle, 2015. Mixed media, 40 × 60 in. Collection of the artist. Photograph by Blair Clark.

BY VALERIE K. VERZUH

In fine art, postmodernism embraces diversity and contradiction, destabilization, and multiple perspectives, as does Coyote — a trickster archetype of indigenous narrative.

Like Coyote, Minnesota Chippewa artist David Bradley is open to life’s multiplicity and paradoxes. “My paintings have been described as narrative art because, when I paint, I tell a story. Like trickster stories, my works are imbued with fantasies and incongruities. Maybe I am a trickster. People usually are struck by the fact that, although they may not see my funny side, my paintings are very funny.”

A trickster counterpart in the contemporary world is the artist who challenges society’s rules and thereby instigates change. Both the trickster and the artist reveal hidden truths, compelling us to acknowledge a world in which there are no absolute truths, just multiple perspectives. Throughout Bradley’s paintings, Coyote appears with cunning regularity. This is, in part, the artist said, because “for the purveyors of ‘high art,’ anything with a howlin’ coyote in it is Santa Fe kitsch.” He learned early in his career, he said, that “the Elaine Horwitch Gallery [which thrived in the 1980s and ’90s], and the artists who showed there, were linked with kitsch, because she sold popular art, including coyotes, the ultimate stamp of schlock.”

In paintings whose seriousness is tempered by trickster humor, Bradley portrays Native American history, human conditions, and personal relationships, and incorporates autobiographical sketches that might be too provocative or divisive in another form. The biographical details of Bradley’s life are critical to understanding his commitment to specific artistic goals and reveal the attitudes, beliefs, interests, and values that have developed out of his experiences, education, and training.

Bradley’s mother was a member of the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe; his father was non-Indian. Born in 1954, he lived with his family in an impoverished Minneapolis Indian community until, when he was four, the Catholic Welfare Services and the Minnesota Department of Family Welfare removed the children from the family home. Bradley and his younger sister were adopted out to a non-Indian family. It was not until he turned twenty-one that he was able to learn details about his birth family and reconnect with his mother and siblings.

Because of his early life experiences, Bradley grew into a man who describes himself as “very independent, often reclusive, and often with trust issues for people and society.” Yet through these experiences Bradley became a painter of keen sensitivity and intelligence with a singular vision and Native American voice. Bradley’s place in the world, that of a person with mixed heritage and complex life experiences, is profoundly present in his artwork in its resolute expression of a heightened sense of injustice.

“My art is about my life. For the past thirty-seven years I have lived near Santa Fe, New Mexico. Before moving here to study at the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA), I was a tumbleweed blowing in the wind. But New Mexico had such an immediate impact on me, I knew that I would live the rest of my life here.”

Much of his artwork is highly personal, revealing many aspects of his life: family, community, connections to specific places and people, his sense of humor and outrage, as well as strongly held beliefs and politics. Family portraits, as well as personal experiences and recollections, are scattered throughout the artist’s work. The painting Arlene Loretto (1989), as well as a sculpture with the same title (2013), are portraits of his wife, a member of Jemez Pueblo who comes from a family of artists. He also delights in depicting the landscape and the town near his home. Lisa’s Café (1994) depicts the town of Madrid, near the Bradley family home outside of Santa Fe. David; his wife, Arlene; and son, Diego Bradley, are seated at the front window. Surrounding them are some of the motifs viewers encounter over and over again in his paintings: the ghost riders in the sky; the Southwest landscape; a representation of two worlds, here in the form of teepees with a satellite dish, Coyote, Whistler’s Mother (from James Abbott MacNeill Whistler’s Arrangement in Grey and Black, No. 1), the Lone Ranger and Tonto, and the ubiquitous cat.

Although his art’s content is both real and imagined, it fits familiar figurative art-historical genres: portraiture, landscape, still life, and genre (the portrayal of scenes of everyday life, including people). His meticulous attention to the surface gives each area of the composition equal significance and resists focal points, inviting viewers to wander the canvas from top to bottom, following lines, shapes, colors, and concepts. His use of strong colors, patterned surfaces, generalized light, absence of expressive brushwork, and overall flatness and linearity enhances the illusory aspect and gives precedence to ideas.

The artist’s dry, highly observant, personal humor successfully bridges the gap between the cartoon and fine art tradition. Intentionally, Bradley constructs seemingly chaotic narratives that combine the unlikely with the absurd, leaving his viewers to ponder how all the elements are related, define each other, and are harmonious. For each viewer, understanding resides in personal, social, and cultural histories as well as in a willingness to question closely held assumptions.

“My art suggests and comments on situations but does not resolve them. I believe my work is accessible to most people, so I allow it to speak for itself. If I try to explain too much, I only put limitations on my ideas, and I’d rather they remain less finite to the viewer. I appreciate listening to other people describe and interpret my work. Each viewer brings something of their own life experiences to it, and their interpretations are often as valid as mine.”

Bradley makes visual this obligation to reach beyond the known in his allusive paintings and motifs based in the work of Belgian painter René François Ghislain Magritte (1898–1967). Found in a variety of guises throughout Bradley’s artwork, Magritte’s man in a bowler hat (from The Son of Man, 1964) was intended by Magritte to be a self-portrait, although only a small part of his face is visible. Both Magritte and Bradley allude to the unknown in their paintings, and both recognize that viewers are often blinded to alternative readings or perspectives by what they “know.”

Another European artist with whom Bradley feels a strong affinity is French artist Henri Rousseau (1844–1910). Rousseau created paintings depicting people and objects in a highly personal version of magical minimalism, in which he expressed both dream and reality through meticulous rendering and simplified form. In Sleeping Gypsy (1897), a woman rests below a lion, which may be interpreted as threatening her well-being, as Bradley’s sleeping Indians lie beneath the threats of foreign culture.

Most of Bradley’s paintings contain or suggest multiple narratives. In The Passage (2012), the artist pictorially positions himself, and the viewer, in the modern world, looking into Indian Country, a place existing on the land, in the hearts and memories of Indian peoples. The Ancestral Pueblo keyhole-shaped doorway and pottery are signs of human life; the rocks with petroglyphs signs of people’s histories, acknowledging an ancient presence but eluding easy translation.

On yet another level, the painting represents a personal life transition: the artist facing his mortality. In 2011 Bradley was diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), commonly referred to as Lou Gehrig’s disease. ALS is a progressive neurodegenerative disease that affects nerve cells in the brain and the spinal cord. The form that Bradley has, bulbar-onset, first attacks the respiratory system, swallowing, and speech. There is currently no cure or even an effective treatment for the disease. Despite the disease, the artist continues to lead an active life with his family and friends, to paint, sculpt, and expand his artistic vision.

One of his latest paintings, completed for the exhibition Indian Country: The Art of David Bradley, at the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture, is Pueblo Feast Day 1984/2014, Full Circle (2015). In it Bradley documents long-cherished relationships as well as new ones: included among the friends and colleagues gathered at the window are museum director Della Warrior (wearing a yellow dress) and me (wearing blue glasses). He also includes a newspaper with the optimistically prophetic headline “CURE FOR ALS FOUND.”

Every year, Southwestern Pueblo communities host feast day celebrations to honor their village’s patron saint, during which they perform dances to maintain harmony with the spirit and natural worlds. The public is generally welcome at these dances and sometimes invited into private homes to share food. At Bradley’s feast day tables, American culture is turned inside out, and dominant relationships are reversed: Tonto, the Lone Ranger, and other icons of American culture become guests at the table — guests in Indian Country — recipients of freely given hospitality.

Feast Day is but one example of how David Bradley works in series to explore the development of ideas around a single theme. Each of his paintings in a series informs the others as one element of an extended narrative. The artist chooses and reuses images and motifs because their subject matter, the literal or visible, is or becomes familiar. Throughout his artwork, Bradley acknowledges that certain iconic images have culture power and communicate meaning almost immediately to viewers. He delights in deconstructing these images to examine how they convey meaning, and then reconstructing them, injecting each with irony for comic effect or critical comment.

The “American Gothic” series is critical and deconstructive of American Gothic (1930), by American regionalist style painter Grant Wood (1891–1942). For many viewers, Wood’s painting portrays the Puritan ethic and virtues that described ideal Midwestern, and later, American character. Bradley builds on audiences’ connection with the original American Gothic to undermine an exclusive American ideal by portraying alternative, more inclusive American couples.

One hallmark of Bradley’s creative process is that he has developed a distinctive visual language, or iconography, which he uses consistently throughout his work. Through this iconography his artwork is linked over time by an idiosyncratic cast of characters, a personal vocabulary of motifs, and a grammar of juxtapositions. For example, to represent the theme “living in two worlds,” he often incorporates money and feathers as opposites. The image of money, he stated, “represents nontraditional culture. It also injects an additional narrative element into my imagery, as it can evoke feelings of prosperity or want, hope or misery.” Feathers, usually eagle feathers, “represent traditional American Indian culture. The bald eagle is the most noble, powerful, fearsome and majestic of birds, and the feathers are sacred to many North American Indian people.” Another avian character, the bluebird, represents “a personal guide who offers individuals advice and support. In my paintings it is usually positioned on or near the shoulder of the person needing guidance.”

Bradley’s paintings are the work of an artist who is a student of American history and a keen observer of his world. Throughout his career he has produced multimedia paintings that are a complex mixture of materials and texture. In contrast to his objective artworks which depict a concrete physical world — albeit in simplified and distorted form — these paintings have a more active development of the surface, using a variety of found materials, as well as the written word. As depictions of Native and non-Native interactions, they juxtapose two different but coexisting ways of interpreting recorded history. They are cogent presentations of facts which goad the viewer to a fuller understanding of the subject.

In Remember Wounded Knee (1990), Bradley depicts two historic American Indian events with special significance for him which occurred in South Dakota. On the morning of December 29, 1890, Lakota chief Spotted Elk and some 350 of his people were camped on the banks of Wounded Knee Creek, on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. Soldiers of the Seventh Calvary, there to arrest Spotted Elk and disarm his warriors, surrounded them. Amid growing tension, a shot rang out. The soldiers opened fire on the camp. Less than an hour later, between 150 and 300 Lakota men, women, and children lay dead. Eighty-three years later, on February 27, 1973, some 200 members of the American Indian Movement (AIM) took control of the Pine Ridge Reservation town of Wounded Knee, declared it the Independent Oglala Sioux Nation, and vowed to stay until the US government met specific demands. They held the town against federal marshals for seventy-one days. Dominating the bottom half of the painting, superimposed with “Remember Wounded Knee,” is an upside-down American flag, a universal symbol of distress. Central to the image are postmassacre photographs of Spotted Elk’s body frozen in the snow and a mass burial of the victims. Topping the composition are bullet holes, a contemporary map of South Dakota, and a United States Postal Service stamp honoring Native Americans.

In a similarly straightforward, unwavering approach, Bradley portrays an event at the conclusion of the Dakota War. On December 26, 1862, in Mankato, Minnesota, the US Army executed thirty-eight Dakota Sioux warriors. They were hung publically on a single scaffold in what was the largest mass execution in American history. Taken in its entirety, the image is of an American flag. Enveloped in Bradley’s characteristic bright, saturated color palette are rope nooses with the words “GUILTY OF BEING INDIAN” below and dollar signs above.

Through these two powerful paintings and others, Bradley reclaims indigenous narrative and gives purpose to an often hideous history. Unlike much of his work, in which humor takes the sting out of racism, these visceral paintings venture into painful territory and hold us there.

Valerie K. Verzuh curated the exhibition Indian Country: The Art of David Bradley, at the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture through January 16, 2016, and is the author of a book by the same name, published by the Museum of New Mexico Press.