Great Space of Land Unknown

A Sampler of the Chávez Library Map Collection

BY PATRICIA HEWITT

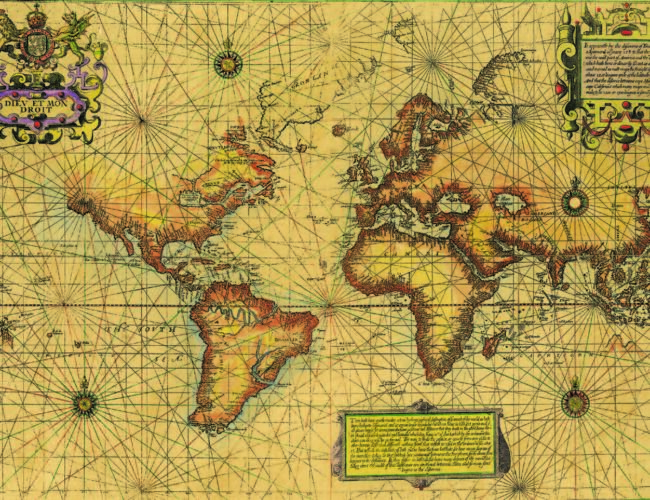

Maps can be educational, symbolic, navigational, political, or recreational, and the map collection at the Fray Angélico Chávez History Library (the Chávez Library) has examples of all of them.

Whether your fancy is for cartoonish tourist maps, topos, or early French maps of the New World, the collection has something for everyone—genealogists, lawyers, hikers, students, railroad fans, and map lovers alike. The maps can be quirky, artistic, colorful, or humorous; all of them help us to discover our world in a different light.

The collection reflects the region’s changing political landscape, from Spain to Mexico to US territory, and New Mexico’s long struggle for statehood. It documents the coming of the railroad, the influx of “Americans” on the Santa Fe Trail, and the creation of a tourist mecca, all leading to the diversity of culture, language, and geography that is today’s New Mexico. Our maps provide rare insight into early explorations of the New World and the historic trade routes of the Southwest. Many show ambitious surveys of the West such as the Wheeler Survey of lands west of the 100th meridian, the line demarking the arid western territories. They tell the history of the American Southwest from the Gadsden Purchase, which facilitated the transcontinental railroad, to the Civil War battlefields of New Mexico Territory, to the coming of the automobile and the ensuing commerce and travel industries. They facilitate research on land grants, water rights, railroad history, early Spanish explorations, and Santa Fe city planning, to name only a few areas of potential investigation.

Over 300 of our maps depict Santa Fe’s history, from its founding as the government seat of northern New Spain to its importance as a trade route on the Camino Real from Mexico City, and as the terminus of the Santa Fe Trail. We have Sanborn insurance maps and city planning maps from the late 1880s to the present day. If you’re curious about the history of your old house or your street, we might have a map that documents it, especially if it’s in the Santa Fe Plaza area.

Perhaps our most significant material is a collection of 1,200 right-of-way maps from fourteen railroad companies that operated in New Mexico, some for only a short time. In great detail, these maps show the businesses, landowners, ranches, and other features near each milepost of the railway line. They are quite rare, and often quite long.

We also have a sizable collection of New Mexico topographic maps, or topos, which show surveyed areas in large-scale detail and relief. They are great for both hikers and researchers, since they include natural and man-made features. The US Geological Survey (USGS), a federal agency, took over responsibility for mapping the country in 1879. The best-known USGS maps are the 1:24,000-scale topographic maps, also known as 7.5-minute quadrangles. These maps might have been produced by a stuffy bureaucratic federal agency, but the place names on the maps reflect both the beauty of the landscape and the somewhat romantic nature of the local vernacular: Rabbit Ear Mountain, Wedding Cake Butte, Little Grande (doesn’t it make you wonder if there’s a Big Grande?), Bitter Lake, Soldier’s Farewell Hill.

A History of the Imagination

Many of our maps show the world not as it was, but as explorers, adventurers, and politicians hoped it would be. Explorers in the New World looked for lost cities of gold, legendary islands, or direct passages to Asia—mythical places sometimes called Cíbola, with its Seven Cities of Gold; the equally wealthy Quivira; or the Strait of Anian. A French explorer’s map from about 1700 shows Quivira, first visited by Coronado in 1541, in what is now Nebraska; the mapmaker remarked that it was “habitué par les Aixais” (inhabited by the Eyeish Indians, who lived in modern-day East Texas and southern Arkansas). Several of our English, French, and Spanish maps show Cíbola, too, thought to be a Zuni city of gold.

Anian, a mythical land mentioned by Marco Polo, was usually depicted in Asia, but we have a map from 1587 by Abraham Ortelius that shows Anian in North America. It also has a strategically placed cartouche (the sometimes elaborate decorative frame around the title of the map) which hides the fact that nothing was known about the South Pacific. And a 1566 Italian map shows a world of legendary places: the Stretto de Anean (Strait of Anian), with Quivira conveniently located nearby, and Civola Hora Granata.

The mythical island of San Borondón was named for St. Brendan, the Celtic explorer who searched for the Garden of Eden. At the end of his famous voyages to the Fortunate Islands, he claimed to have seen a phantom island, considered a paradise on earth. “I. de S. Borondon que l’on croit fabuleuse” (Saint Brendan’s Isle, believed to be fabulous, in the sense of “mythical” or “storied”) is marked on one of our French maps from 1700.

We have many maps that show California as an island, even long after it was shown not to be one. According to a 1510 novel by Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo, the Island of California is situated “very close to the side of the Terrestrial Paradise; and it is peopled by black women, without any man among them, for they live in the manner of Amazons.” Apparently, the myth was just too fabulous and romantic to give way to geographical reality.

The 1840s saw major expansions of the land area of the United States. An 1848 map by Ephraim Gilman of the US General Land Office is an opportunity to glimpse various political machinations after the Annexation of Texas in 1845, and the acquisition in 1848 of Oregon Territory from the British and large areas of the modern-day Southwest under the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo.

As most New Mexicans know, the Republic of Texas had defined its boundary on the south and west as the Rio Grande from mouth to source, meaning Santa Fe and all the settled parts of Mexico’s northern province of New Mexico would have been part of Texas. The 1848-era Gilman map shows this claim, and on it, California extends east to the border of New Mexico and the proposed Nebraska and Minnesota territories. A strange looking map indeed!

Seeing the World through Old Eyes

Part of the fun of looking at old maps comes from depictions of what was then unexplored territory, and seeing how the New World was described and drawn. Some cartographers were forthright enough to acknowledge that they did not know what existed in some areas. Thomas Kitchin indicated a “Great space of land unknown” on a 1777 map of what is now the Midwest. Many maps resort to “Terra incognita,” “Mare incognita,” or on a map from 1570, “Terra Australis Incognita” (unknown land of the South), but as explorers began to literally fill in the blanks, these phrases disappeared from later maps.

While there is no “Here be dragons” on our maps (apparently this phrase is something of an urban myth: there are only two known globes which include this phrase), we do have some drawings of sea serpents and other fabulous animals and birds. Tricky navigational waters were marked with warnings of heavy vegetation near what is now Bermuda, with “herbes flotantes sur la mer.” This is most likely what we now call the Sargasso Sea, named for the sargassum seaweed that is abundant there. While there were stories of ships being stranded in the area, they were more likely to be trapped by calm winds than by “herbes” (or by the Bermuda Triangle).

Mapmakers knew their descriptions of the New World were of great interest. A reproduction of a map from 1600, mentioned by Shakespeare in Twelfth Night (“He does smile his face into more lines than is in the new map with the augmentation of the Indies” [Act 3, Scene 2]), has this lovely inscription to its audience: “Thou hast here, gentle reader, a true hydrographical description of so much of the world as hath beene hereto discovered.”

Toontown

One of the great things about looking at old tourist maps is remembering all those places we have forgotten—the restaurants, the shops, the schools, where the bank used to be—it’s a walk down memory lane. Pictorial maps have their own style and flair that make them accessible to a wide audience. Whether they show a bird’s-eye view of a particular city or guide tourists to its restaurants, they represent a hands-on approach to the local attractions. While they may be more artistic than accurate, they are fun to look at, and they invite us to reminisce. Some, of the satirical variety, take a particularly humorous look at the Santa Fe worldview.

The Chávez Library also has pictorial maps of ghost towns, hunting and fishing guides, and vacation maps to help you plan your next day trip to an old mine or a battlefield. With over 1,100 road and highway maps, and plenty of recreational and tourist maps, there is something for everyone.

Cataloging the Collection

In 2011, the Chavez Library was awarded a $179,600 grant from the Council on Library and Information Resources (CLIR) to catalog its map collection, a three-year effort which helped researchers and the public discover and make use of its resources. The council’s award program, Cataloging Hidden Special Collections and Archives, sought to increase awareness of collections of substantial intellectual value that were unknown and inaccessible to scholars. CLIR administered this national effort with the support of generous funding from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

Now that most of the maps have been cataloged (approximately 6,000 are finished, with another few dozen to go), searchers are able to locate maps by topic—commerce, immigration, tourism, water rights, land grants—rather than just by place and date. In the process, we’ve learned a lot about map cataloging (for example, how to measure a map to its “neat line,” and how to figure out the equivalent in feet of Spanish varas or chains). Now we would like to secure a grant to digitize the most interesting items in the collection.

Bibliography

Robert Julyan. The Place Names of New Mexico. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1996.

Dennis Reinhartz. The Art of the Map: An Illustrated History of Map Elements and Embellishments. New York: Sterling, 2012.

United States Board on Geographic Names. Geographic Names Information System (GNIS).

Patricia Hewitt is the senior cataloger at the New Mexico History Museum’s Fray Angélico Chávez History Library.